Calling all Movers Shakers + Quakers

Offering 60+ eateries, stores, and entertainment venues, Shop Penn is giving you plenty of reasons to stay and play around campus this semester.

Wants Needs + Must-Haves

Shop Local. Shop Penn.

#SHOPPENN

@SHOPSATPENN

Foodies

Deliveries + Shopping Sprees

5 7

30 The Ins and Outs of Sexual Health at Penn

From supportive communities to STI testing sites, Street is rounding up resources.

34 What We Talk About When We Talk About Sex

Turns out, it’s a bit more complicated than just ‘you and me.’

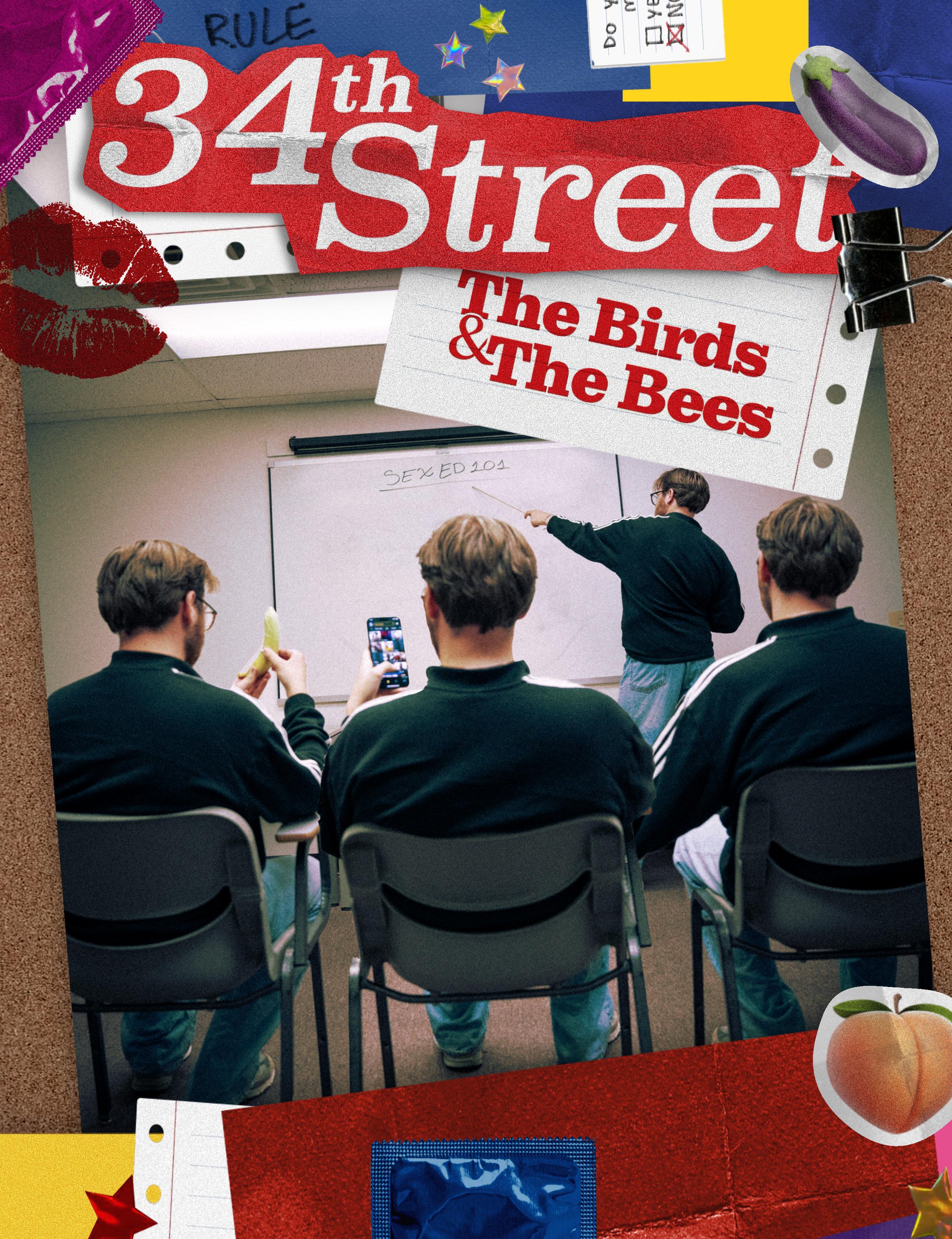

The Birds, the Bees, and Street

Untraditional words of wisdom from writers who have been there, done that

Ego of the Month: A. A.

Graduate student, changemaker, and community builder: This senior does it all.

15 Strike a Pose!

The essence of Philly Ballroom and its 36 years of gracing the dance floor

10 40 The Life of Real–Life Cupid

You might not know his name, but you know his art.

The Death of Physical Media and Its Brewing Renewal

How a generation raised on streaming seeks comfort in the rituals of media ownership

The Birds and The Bees

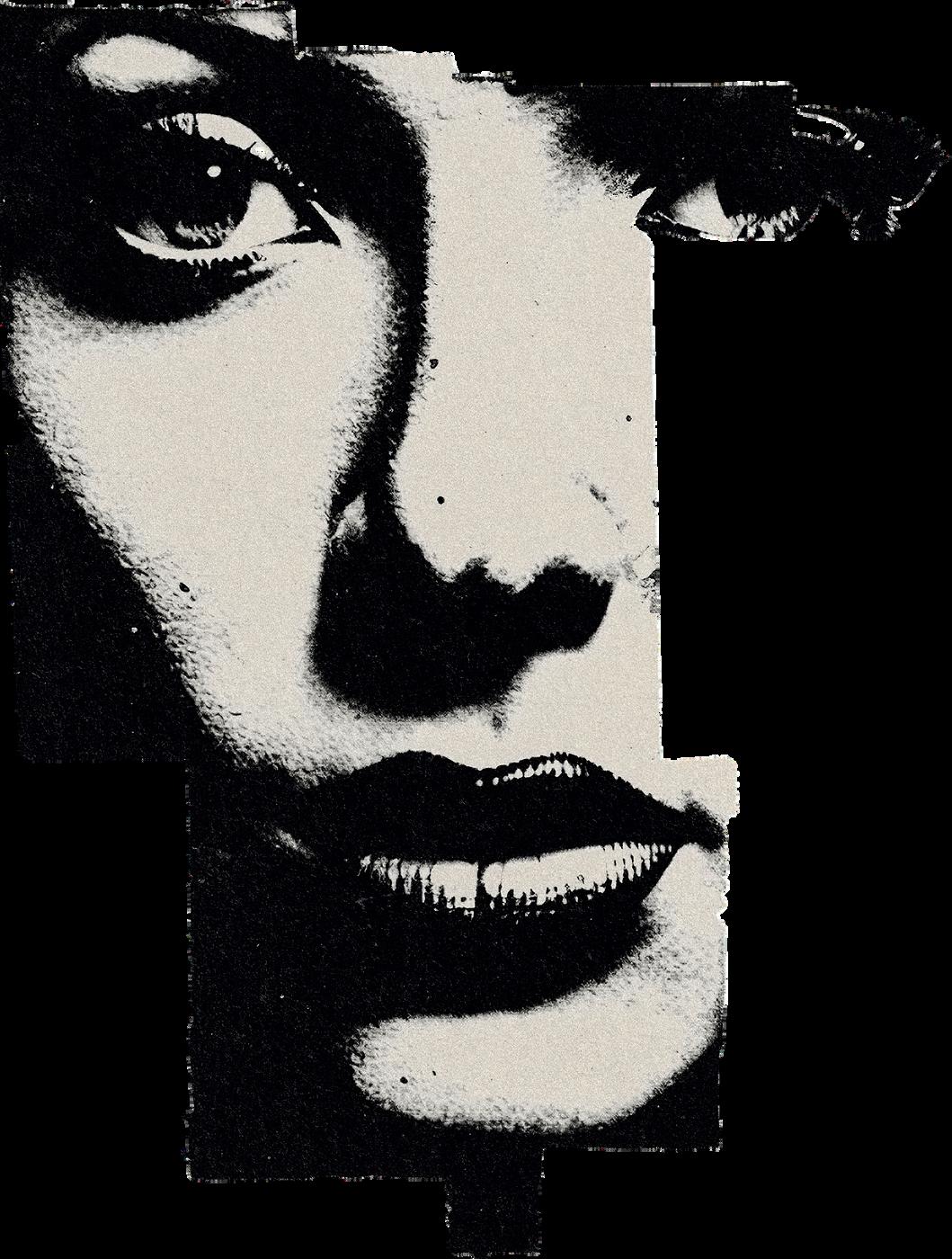

ON THE COVER You, me and sex at Penn. Things might get messy.

By Jackson Ford and Insia Haque

Notes from a sex–ed student perpetually learning

Midway through my senior year of high school, my mom and aunt sat me down in the kitchen with a college sex–ed pop quiz.

“What do you do when you hit it off with a nice older dental student at a party, and all of your friends say they’re heading home so he offers you a ride?” Say no—go home with your friends instead. “How do you avoid being roofied?” Hold your own drink. “Norah, you shouldn’t be drinking!” Fine, fine—don’t drink. “Will you tell me when you have sex?” Mom!

My parents never sat me down and had a classic “birds and the bees” talk. In fact, at 18 years old, this was probably the most my mother and I had ever even touched upon the topic to that day.

My Texas education had prepared me well to solve differential equations, write essays in a matter of hours, and discuss UNCLOS with the passion of a seafarer. It gave me absolutely no tools to decipher what it meant when a girl offered to walk you home after DFMOing at a party. In fact, I had absolutely no clue what a DFMO was.

So, I arrived at college suddenly confronted by thousands of young people doped up on hor mones and newfound freedom.

During freshman year, my friends and I would go to parties and awkwardly attempt to “hook up” with people—whatever that meant— just to say we had done it. I talked one of my guy friends through how to have sex with a woman, to which he responded, “You put what where?” (it wasn’t long before he came out). There was a phase where my female friends would go to frat parties and make out with each other for “fun.” It ended once they got boyfriends soon after.

The trial by error doesn’t end with freshman year. To this day, on each Sunday an assortment of Street members show up to our all–staff meet ing covered in hickeys that they haven’t quite mastered covering. I have heard more than one horror story of people who decided to room with their partner, only to break things off weeks be fore moving in. Personally, as I enter senior year of college in my first long–term relationship,

I’ve been forced to understand boundaries and codependency in entirely new ways.

No matter how comprehensive your public school sex–ed, how low your precollege Rice Purity score, or how many seasons of The Sex Lives of College Girls you’ve watched, I don’t think it’s possible to ever be fully prepared for the complexities of college sexuality.

“The Birds and the Bees” issue is the college version of those weird puberty books you got in middle school. Your big siblings at Street are fiending to answer the ever–present question that you never thought to ask, from “does oral count as a body?” to “Is Gen Z even having sex?” We’ll offer a snapshot of the vibrant queer community on campus and share our own embarrassing stories of awkward first dates and failed hook–ups. Our feature will dive into how Penn administrators and student groups seek to address the fragmented sex–ed experience of our student body.

Before you go any further, here’s the wisdom I can offer: You’ll probably forget half the things you’ll learn in CIS 1600 or your writing seminar. But you can’t shake the lessons that lead to you showing up to class in a turtleneck and sunglasses.

And make sure you own a turtleneck.

SSSF,

EXECUTIVE BOARD

Norah Rami, Editor–in–Chief rami@34st.com

Jules Lingenfelter, Print Managing Editor

lingenfelter@34st.com

Nishanth Bhargava, Digital Managing Editor bhargava@34st.com

Fiona Herzog, Assignments Editor herzog@34st.com

Insia Haque, Design Editor haque@34st.com

EDITORS

Copy Editors

Asha Chawla and Garv Mehdiratta

Deputy Assignments Editor

Samantha Hsiung

Features Editors

Bobby McCann and Chloe Norman

Section Editors

Sarah Leonard, Focus Editor

Kate Cho, Style Editor

Anissa T. Ly, Ego Editor

Sophia Mirabal, Music Editor

Logan Yuhas, Arts Editor

Liana Seale, Film & TV Editor

Multimedia Editors

Jackson Ford, Street Photo Editor

Danielle Jason, Street Social Media Editor

Makayla Wu, Design Editor

Cassidy Whaley, Social Media Editor

THIS ISSUE

Deputy Design Editors

Kate Ahn and Anish Garimidi

Design Associate

Chenyao Liu

Muse of the Issue

Vivian Yao

SUMMER STAFF WRITERS

Justin Paul Abenoja, Staff Writer

Will Cai, Music Beat

Diemmy Dang, Features Staff Writer

Sadie Daniel, Focus Beat

Celina Jiang, Staff Writer

Anjali Kalanidhi, Staff Writer

Ananya Karthik, Staff Writer

Jack Lamey, Style Beat

Xihluke Marhule, Film & TV Beat

Conor Smith, Staff Writer

Emily Whitehead, Staff Writer

LAND ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

The land on which the office of The Daily Pennsylvanian stands is a part of the homeland and territory of the Lenni-Lenape people. We affirm Indigenous sovereignty and will work to hold the DP and the University of Pennsylvania more accountable to the needs of Indigenous people.

CONTACTING 34 th STREET

MAGAZINE

If you have questions, comments, complaints or letters to the editor, email Norah Rami, Editor–in–Chief, at rami@34st.com You can also call us at (215) 422–4640.

www.34st.com © 2025 34th Street Magazine, The Daily Pennsylvanian, Inc. No part may be reproduced in whole or in part without the express, written consent of the editors. All rights reserved.

The Birds, the Bees, and Street

Untraditional words of wisdom from writers who have been there, done that

BY STREET STAFF

Design by Chenyao Liu

On the night of my 21st birthday, sitting at a booth in Local 44 with a lavender hibiscus kombucha marg in hand, I received a revelatory piece of advice from a dearly beloved friend about my embarkment into a new era of life: “I think your 20s are all about having regrettable sex.” Now of course, the sentiment is not meant to encourage one to engage in unsafe,

emotionally harmful, or dangerous sex. Rather, it acknowledges that the foray into adulthood is not so glamorous, and those sexual escapades are often a lot more awkward than you may expect. I mean, let’s be real. You’ve gotta get through the Lena Dunham Girls stage of life before you can even dream of living an episode of Sex and the City Young sex is messy and embarrassing,

and like most things in life, there is a steep learning curve. Street has had its fair share of uncouth trysts and inopportune rendezvous. Learn from our mistakes, or just laugh at us. But there’s no shame in figuring things out, even if it leaves a twinge of regret the next morning.

— Jules Lingenfelter, Print Managing Editor

I didn’t know that lesbians could get STDs until the end of my junior year of college, when my best friend and her—actually, I don’t know what to call him, but for all intents and purposes, we can say buddy—sat me down in the Kelly Writers House yard and explained female anatomy. I blame my Texas sex education, which consisted of close–up photos of STDs and no bigger–picture explanation of how you actually got those nasty–looking popcorn infections. My real sex ed in high school consisted of indulgent friends who looked me in the eye and talked me through how to ask someone out, what counts as sex, and far too graphic descriptions of how to do it. And in college, my friends were the ones who swooped back in to fill the gaps.

Before arriving at college, I’d had several crushes. These individuals contained varying personalities and looks, but held one similarity: A relationship would never begin with any of these love interests. That microinfluencer half didn’t know I existed, while others were minding their own lives hours away.

Now, within a more realistic pool of dating candidates, I still find myself crushing on people I can’t have. While this mentality always results in disappointment, there remains something enticing about it—something I’ll spend my life trying to discover. Until then, I will remain enamored by my imaginary spending of time with unobtainable people.

— Serial Crusher

— Sex–Ed Student Perpetually Learning

Not every hookup makes the roster because body count is both a vibes– and performance–based metric.

It resets if you go to confession—but only Roman Catholic confession. For a spiritually sanctioned reset, consider joining a crusade.

Doesn’t count if you were drunk. Or if it happened on church or church–adjacent property, including vaguely religious frats. That’s between you and God and his pledge class. If you never saw his driver’s license and later found out he’s from the suburbs (Wellesley, Mass. isn’t Boston). God knows you’re lying, and He also knows you sucked at being an altar server. If he didn’t talk you through a LinkedIn update during aftercare. If you forget his name within a week and maybe accidentally remember his dad’s name instead—that’s not your fault. That’s a census error. If he thought you finished but you didn’t, and he was so weirdly, pathetically earnest about it that telling him would’ve felt like killing a puppy behind a barn with a crowbar.

Finally, if you wouldn’t even grimace–smile at him on Locust Walk, then spiritually, emotionally, biblically—it doesn’t count.

— The All–Knowing Hookup Oracle

Learn from our mistakes, or just laugh at us. But there’s no shame in figuring things out, even if it leaves a twinge of regret the next morning.

Most people who know me now would not recognize the person I was when I first came to Penn. This is for a variety of reasons—I’d like to think I’ve really matured and grown into myself—but also because I was once a young frat–hopping first year who lived to party three nights a week. And with those adventures came some classically bad hookups. My first party ended with awkward fumbling in my dorm, only to see him going out with another girl less than 24 hours later. After a night spent in another’s bed, he attempted to convince me that I didn’t really need to go to the New Student Orientation consent circle—yikes! Or the morning after Halloween, when a guy told me it would’ve been his third–year anniversary to the day with the girlfriend he just broke up with earlier that week. Oh, poor first–year me, who was utterly confounded by the men on campus and swore off dating for nearly a year because of it.

— Retired Party Girl

I only use Hinge when I’m abroad— Penn students and old high school faces feel too familiar, too risky. Seniors are too easy to fall for, and heartbreak is too easy to find. Instead, I break my own heart differently, finding love thousands of miles away, hiding from the hookup and breakup culture that Penn’s dating scene provides. My mom says I should kiss and sleep with whoever I want—emulate her own college “slut era.” Maybe she’s right. But I like my foreign crushes and kisses. I like to fall in love within days and pine for years after. I’m not staying here after graduation, so my wine dates and walks on foreign shores tie me to the future I dream of, far from here.

— Lover of Everywhere but Here

When I first saw Lexa from The 100 at 12, I thought something was wrong with me. The feelings everyone talked about having for boys? I never had them. But I did have them for Lexa—and for the older girl at school with black hair and silver jewelry. Now, I know there was nothing wrong with me. I’m just gay ASF. Seeing the beauty in women helped me see it in myself. I wish I could tell my 12–year–old self that being gay isn’t wrong—it’s beautiful.

— Keeping It 100

Hey, first year reading this, hope you are settling in alright. I have to break some surprising news to you. You’re going to have to date an artificial intelligence software. What? Yes, you. Take your pick. ChatGPT, Gemini, maybe a replica of Game of Thrones’ Daenerys Targaryen? Just probably not Grok. I’m guessing you are too woke for him if you willingly picked up Street. “But what about meeting my future husband in the Quad?” Shut up. You threw that out the window when you enrolled here. Your human options at Penn range from Blackstone to BlackRock. So play it safe, sext a chatbot. Everyone’s doing it.

— Individual Concerned About AI k

Hometown

Dallas

Major

Philosophy, politics, and economics and a master’s degree in nonprofit leadership

Activities

Penn Bangla, Queer Muslims at Penn, United Minorities Council, Penn Queer and Asian Society

For A. A. (C ’26), free time is hard to come by at Penn. As the president of Penn Bangla and Queer Muslims at Penn—and a board member of the United Minorities Council and the Penn Queer and Asian Society—the senior is busy building community and fostering safe spaces for marginalized students across campus. An organizer, activist, and leader, A. has helped lead protests against gentrification in Philadelphia, spearheaded the planning of Penn’s Intercultural Fair, and founded a club to support queer Muslim students. To add to their busy schedule, A. is also submatriculating, pursuing a master’s degree in Nonprofit Leadership from Penn’s School of Social Policy and Practice. Whether it’s in the classroom, on campus, or within the Philadelphia community, it’s clear that A. is dedicated to driving change with care, grace, and empathy.

What inspired you to start QMAP?

I went into the LGBT Center freshman year, and I saw some things about QMAP. I reached out to the person who technically founded it, and they graduated five or four years prior. So I started it with my friends, because there aren’t many queer Muslims on campus. I started it last year as a kind of safe space. I think it was mainly because I feel like I was raised in a

EOTM

Graduate student, changemaker, and community builder: Creating community for this senior is all about intersectionality and nuance

BY DIEMMY DANG

Photos courtesy of A. A.

very, very Muslim household. My parents are extremely religious, so gender, sexuality, and being queer are things that you definitely did not talk about. I feel like going to Penn and being in a completely different state from my family let me explore that during freshman year, and then I wanted to create a safe space for incoming freshmen and underclassmen to have that space during my junior year. So that was mainly what I did junior year: I founded QMAP—or refounded it, because it was kind of dead before.

What kind of community do you hope to foster through QMAP?

I think QMAP has a constituency of five to six people. The sample size is very, very small, and so when I try to do QMAP things, it’s typically through a partnership lens, where we have a few events by ourselves. We do self–reflection and things ourselves to gain that kind of camaraderie with ourselves, but then we also do a lot of partnerships with Penn Q&A. We did a

lot of stuff with Penn Bangla, because I’m president of Penn Bangla, and do a lot of partnerships with other cultural organizations. I feel like being queer and Muslim is such a taboo topic that having connection to all of these cultural organizations makes it feel as though we are welcome in some other communities as well.

You are part of several student affinity and advocacy groups, and many celebrate the intersection of multiple different identities. What does intersectionality mean to you, and what has your experience been with intersectionality at Penn?

I think intersectionality and intersectional groups at Penn are the places where you’re going to meet a lot of nuanced people. I think the intersection of being queer and Asian, or queer and Muslim, puts you in such a curious space that it’s very difficult to find people who feel similarly or think similarly to you. So, you have a very small group, but it is

an extremely tight–knit group, because a lot of you have had the same experiences growing up or felt the same things or view the world in the same way. Initially, I felt like I had to cater to a lot of what the general LGBTQ+ consensus was on how to be queer and how to be Asian as two separate things, but now I’m able to celebrate those two things together. The same thing is true for being queer and Muslim, or all of these things together.

Do you feel like your master’s program classes have complemented your work as a student organizer?

I feel like for my master’s program, a lot of the classes that I’ve taken have been taught by amazing professors. A lot of them have similar outlooks on the world that I do. “Social Finance,” taught by Andrew Lamas, was really, really good. And I’m now taking classes this upcoming semester about poverty and building poverty–informed communities, which is taught by a refugee lawyer, which is what

I want to be. So that has been really exciting. I took a class with the same professor in freshman year, too. I recommend that class for everybody. It’s called “American Race: A Philadelphia Story.” It was really, really insightful to learn about Philadelphia, because I did move from Texas, but I think there are certain classes which I think just align with my outlook on the world and how I view gentrification or nonprofits and the role of non–governmental organizations, whereas other ones are very much consulting oriented or business oriented. They teach you about finance and how to create consulting projects for these nonprofit organizations. It’s definitely been a hurdle for me to jump, because it is very preprofessional in that way, and I’ve tried to avoid that as much as I could during my time at Penn.

Where do you see yourself after graduating from Penn?

My number–one aspiration is to live in New York and work for the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees for a few years. After that, I hope to then go to law school, hopefully get my law school fully paid for, and then become a refugee lawyer, own my own agency, and have a nonprofit of refugee lawyers. That’s my aspiration. Hopefully, I’ll get to the UNHCR.

I think this interest kind of started freshman year. In the summer, I got to go to Bangladesh, which is where I’m from, and work in one of their refugee camps in Cox’s Bazar, which is for the Rohingya refugees and is the biggest refugee camp in the world. From there, I really, really fell in love with the organization and how they work alongside refugees instead of for them. A lot of these refugees are working in these legal agencies because it’s easier to hear from someone who is from your community. That was a really big part. I think the fact that they employ these refugees to work in their organizations is something that I want to carry on if I become a nonprofit organization leader in the future. k

Go–to Philly restaurant?

Zhangliang Malatang in Chinatown

Best campus study spot?

The ARCH patio

Comfort Movie?

Bajirao Mastani

Favorite music album?

Jaago by Lifafa

There are two types of people at Penn… Whartonized people and non–Whartonized people

And you are?

Non–Whartonized

The Life of Real–Life Cupid

What a Philadelphia matchmaker thinks Materialists got wrong about love, and what it surprisingly got right.

BY SAMANTHA HSIUNG

Graphic by Kate Ahn

Many things in life can be solved with formulas—like a calculus problem or the optimal fantasy football lineup. But not love. Especially not in the City of Brotherly Love.

The latest release of Materialists foregrounds the quantitative nature of modern love—laundry lists of requirements, meal transactions, and emotional calculations. The film follows Lucy Mason (Dakota Johnson), a New York matchmaker inspired by writer and director Celine Song’s own experiences as a matchmaker. Lucy chases perfect matches as much as she chases love in her own life, which arrives imperfectly—in the form of John P (Chris Evans), her ex-boyfriend. John doesn’t check any of her boxes: He’s half–jobless (an aspiring actor), broke, and the kind of partner that her gamified approach to love would filter out.

Yet even after watching the movie, a question persisted: What even is matchmaking? Does that even exist in Philadelphia, or at Penn, and is it just like how it’s portrayed in Materialists?

That’s a question that Lauren Daddis—a Philadelphia–based matchmaker for Three Day Rule, a matchmaking company—can answer.

While Materialists is deeply entrenched

in the fast–moving, often faceless sprawl of New York, Daddis’ world is slightly less cinematic (though no less interesting). Daddis notes that Philadelphia is a place where “everybody knows everybody,” especially through networks established by institutions like Drexel University, Penn, and Temple University, which attract hordes of students and staff. With so many college students in the city, most eligible bachelors and bachelorettes already know each other, or know someone who knows someone they’ve dated. “When people go

to swipe on apps, they’re just getting burnt out and seeing the same 30 people,” Daddis emphasizes.

In fact, it is the bubble–like nature of Philadelphia that Daddis capitalizes on. Many of Daddis’ clients come to her seeking the privacy that Three Day Rule offers them, which is an alternative to the visibility and overlap that comes with dating apps. “They don’t want to be on the apps,” Daddis explains. “They don’t want to see people they know, see people they’re in class with. Even professors, they don’t

want to see their students.”

One of the darker plotlines in Materialists is centered around Sophie (Zoë Winters), one of Lucy’s clients, who is assaulted by Mark—one of her other clients. After Lucy finds out about the assault, she breaks down and ravages through her notes on Mark in search of red flags that she may have missed. However, she isn’t able to scavenge anything substantial from her notes that would’ve informed her about Mark’s behavior. When asked about how she felt about the scene, Daddis says that

it doesn’t reflect how she approaches her work and even made her “a little mad,” as Lucy had only written very superficial things—related to money and height— about Mark in her notes. “That was upsetting, because I was like, you didn’t do your job,” Daddis says. “I like to think that we go much deeper than that. To really find, a partner for someone, it needs to be more than [that].”

At Three Day Rule, the matchmaking process is certainly deep, and much more intricate than a swipe–based app. Once a

matchmaker is hired, they spend time getting to know the quirks and traits of their clients and understanding their clients’ preference in a partner; they figure out their clients’ non–negotiables while probing at other boxes that the client might want checked off. Then, the matchmaker begins interviewing as many people as they can on behalf of the client—whether it’s the clients of other matchmakers, former clients, or people who’ve signed up to be in Three Day Rule’s network without formally hiring a matchmaker.

Daddis always schedules video calls with potential matches for her clients instead of relying solely on written profiles or phone calls. “I think it’s really important to see the body language, the eye contact, and how they answer questions,” Daddis explains. “People can do great with their voice, but if their shoulders are up to their ears and you can see they’re stressed out, or they’re lying or something, then I’ll know.”

The questions that matchmakers ask potential matches are razor–sharp, designed to cut through the surface and reveal as much about the potential match as possible. “‘Tell me about yourself. What are you looking for? Why have your relationships failed? Do you know why? Tell me about your relationship with your mother,’” Daddis says, firing sample questions in rapid succession. “I ask about their upbringing or their relationship with their siblings.”

Beyond intimately understanding the matches, the questions are also intended to gauge a sense of the match’s communication style. Once the matchmaker feels like they have found a good match for their client, they write up a biography about the match and share photos of the match with their client. It’s not just matchmakers who are asking questions throughout the process; Daddis’ clients often bombard her with questions about why she believes the match is a good pairing.

Now, on to the fun part—if both parties demonstrate interest, they proceed to the next point: a date. At that point, the matchmaker momentarily steps out of the frame and follows up with both the client

and the match to hear how things went.

“Some of the times it’s my client who wasn’t really into the match, and then the match was really into my client, so then I handle that.” Daddis says. “There’s really no typical [outcome]. Once I introduce them, I kind of saddle up and go for the ride, because I can’t control how anything happens.”

Though the ride can be quite turbulent, many clients try to exert control where they can, such as by drawing hard boundaries around what they want. Common filters include ethnicity, politics, and religion. Among women, though, one preference surfaces more than any other: height. “That’s the one that makes me chuckle, and it’s funny, because the women that are sticklers for heights usually end up having really great dates with men that they would not swipe on otherwise, if they didn’t have me to push [them] and be like, ‘What’s one inch?’” Daddis laughs.

These kinds of interactions, Daddis says, are exactly what Materialists got right. The film’s depiction of matchmaking was oversimplified and slightly inaccurate, but the portrayal of clients felt uncannily real. “Those things were verbatim things that people say to me: what they want, what they deserve, what they are hoping for, their hopes and dreams,” Daddis says. “All of those things, they were spot on.”

In the end, matchmaking isn’t about manufacturing the perfect partner. Rather, it’s about helping people expand their idea of what love can look like. Sometimes, that means nudging someone past a rigid checklist. Other times, it means opening a door they didn’t even know was there. Daddis recalls a female client who had only dated women and came to her wanting to explore dating men for the first time. “She’s marrying a man now,” Daddis says. “People come to us for all different things.”

Daddis’ advice for Penn students who are looking to couple up is as predicted—to sign up for Three Day Rule.

“At least just put your name in the hat,” Daddis says. “It’s just another place to make yourself available.” k

The Rise of ‘Girl TV’: Why We’re All Watching Fleabag’s Daughters

Messy, self–aware women on screen still resonate in a world that expects them to have it all together.

BY ANANYA KARTHIK

Graphic by Kate Ahn

If there’s a defining genre of television and film for women in their late teens and 20s today, it’s what might be called “girl TV.” The term refers to pieces of media that center on messy, self–aware, and often self–destructive female protagonists who narrate their own lives with a blend of brutal honesty and ironic detachment. These are characters who oscillate between shame and self–celebration, who live in small apartments and make bad decisions in

good lighting, and who seem to exist in a world where the line between therapy and spectacle is intentionally blurred. The genre’s canon includes Fleabag , Lady Bird , and Barbie , and while each film or series has its own flavor, together they reflect a deeper cultural fixation: a collective fascination with women behaving badly and taking control of their own stories.

What unites these works isn’t just a focus on women’s lives, but how those

lives are framed. Their protagonists are narrators, performers, and unreliable witnesses to their own dysfunction. They speak directly to the audience, both literally—as in Fleabag , where Phoebe Waller–Bridge’s character breaks the fourth wall with smirks and side eye—and structurally, as in Lady Bird , where Greta Gerwig’s script invites the audience to sit in the tension between self–delusion and self–awareness. Barbie pushes this even further,

using hyper–femininity, satire, and self–parody to not just dissect the impossibility of living up to what a woman is “supposed” to be, but to deliver that message in dialogue with its audience. The film explicitly acknowledges its own contradictions and invites viewers to laugh, cringe, and reflect alongside it. These characters are not role models, and they’re not trying to be. They’re telling us, in no uncertain terms, that they are selfish, impulsive, and sometimes cruel. Yet there’s something in the chaos, the humor, the refusal to behave, that keeps us watching—sometimes with admiration, sometimes with unease, but always with our full attention.

The rise of “girl TV” coincides with a larger cultural shift in how women are allowed—or expected—to perform their lives in public. In the 2000s, media representations of women were defined by a kind of curated aspirationalism: the Carrie Bradshaws and Serena van der Woodsens of television were glamorous even in their messiness. Their problems were real, but they were also softened by wealth, style, and the promise of redemption. Fleabag marked a break from this tradition—when it premiered in 2016, it felt revolutionary not just because its protagonist was flawed, but because the show refused to grant her a neat resolution that “excused” her behavior. Her story was hers to tell, and she told it without apology.

Lady Bird , released a year later, captures a similar ethos in film. Christine “Lady Bird” McPherson (Saoirse Ronan) is both endearing and insufferable, a teenager who fights with her mother, lies to her friends, and romanticizes her own life to the point of absurdity. Lady Bird was not a story about triumph, or even about resolution; it was a story about a girl who doesn’t know how to be—a young woman caught between the roles she’s told to play and the person she might become, a woman flailing through friendships, family expectations, and her own inflated sense of self. Lady Bird acutely captures the silent desperation

of trying to reinvent yourself while still being tethered to the people and places that shaped you.

In 2023, Barbie took this even further, becoming a global phenomenon by explicitly framing the female experience as one of cognitive dissonance: You can be everything and nothing, powerful and powerless, an object and a person, all at once. In one monologue that’s already become a cultural touchstone, America

These characters are not role models, and they’re not trying to be. They’re telling us, in no uncertain terms, that they are selfish, impulsive, and sometimes cruel. Yet there’s something in the chaos, the humor, the refusal to behave, that keeps us watching.

Ferrera’s character gives voice to what many women already feel: “You’re supposed to love being a mother, but don’t talk about your kids all the damn time. … You have to answer for men’s bad behavior, which is insane, but if you point that out, you’re accused of complaining.” Like Fleabag or Lady Bird , Barbie gives voice to the latent contradictions that structure women’s lives, pulling the audience directly into the tension between self–awareness and self–critique that defines “girl TV.” It’s a self–referential, confessional project, now with a blockbuster budget.

The self–aware genre of “girl TV” res -

onates with younger viewers, especially women, because it mirrors how we consume and create content in 2025. Social media has trained us to view our lives as material for storytelling: We only recognize ourselves through Instagram captions, TikTok voiceovers, and BeReal snapshots. Similarly, the women depicted in “girl TV” are both protagonists and influencers—curating, self–critiquing, and inviting the audience into the performance of their pain. They are not “likable,” but they are captivating.

Of course, there’s a risk that “girl TV” can become a genre with diminishing returns. As more shows and films adopt the formula of chaotic womanhood, the aesthetic of messiness can start to feel less like a radical act and more like a branding strategy. The “hot mess” character has become a type in its own right, complete with the trappings of aestheticized dysfunction: oversized button–downs, artfully messy apartments, and a curated playlist of sad–girl pop. At times, it can feel like we’re watching a genre parody itself—an endless loop of women looking into the camera, confessing their flaws, and cueing up Phoebe Bridgers.

Still, for many viewers, the appeal of “girl TV” endures in its refusal to sanitize the female experience. These stories don’t offer neat moral lessons or redemption arcs. Instead, they present a world where women can be funny, petty, angry, and sad—sometimes all at once—and where that complexity is the point, not a problem to be solved. If “girl TV” is a mirror, it’s a deliberately cracked one, reflecting back the contradictions of a generation raised to perform empowerment while still navigating the same old pressures of gender, class, and identity.

In the end, watching Fleabag ’s daughters spiral through their crises isn’t just entertainment. It’s a kind of collective processing: a way to acknowledge that we are all, in some way, performing throughout our own messy, imperfect lives. k

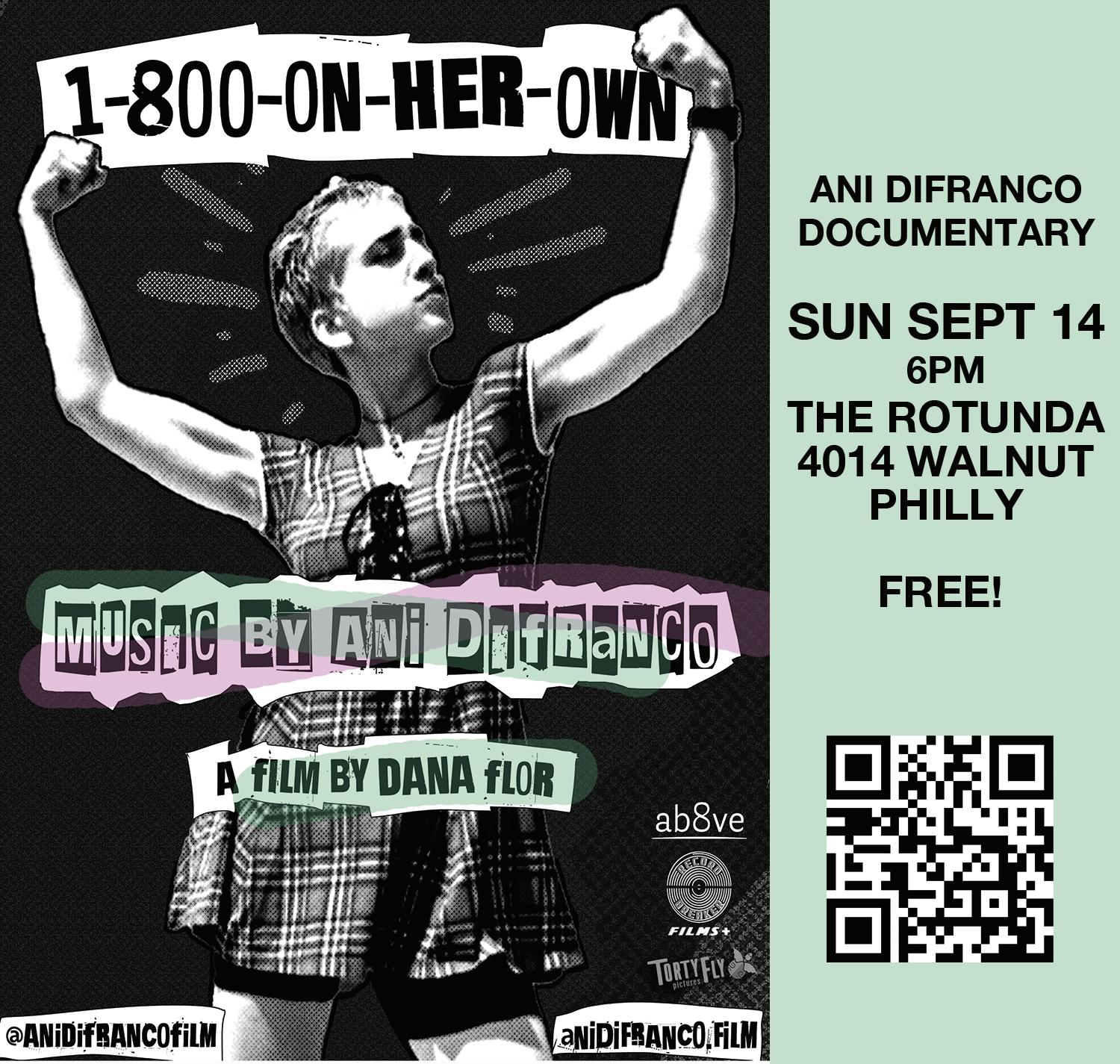

Strike a Pose!

The essence of Philly ballroom and its 36 years of gracing the dance floor

BY XIHLUKE MARHULE

Graphics by Kate Ahn

Iam one of the first to arrive. The room is stuffy but bearable. I set my bag and skateboard down and get ready to learn something new. Homages–in–painting, rudimentary audio equipment, and loose pieces of furniture fill the room. Two dancers across the room are stretching to warm up. As more people stream in, the energy lifts. Practice eventually starts, and from the get go, I realize I will not be able to keep up. So I watch.

Hands. Catwalks. Duckwalks. Spins and dips. Floor performance. Death drops. Opulent wigs and costumes, extravaganza, charm and wiles, all in fierce competition. To the uninitiated, a simple collage of words. For those in the know, a call to witness. For participants, these words mean everything.

This is the essence of vogue.

A far cry from its quaint beginnings in trans, queer, people–of–color communities, the modern ballroom scene has taken the world by storm, permeating throughout pop culture, from initial hits like Paris is Burning, to millennial–age classics like hit television series POSE and RuPaul’s Drag Race. Ballroom lounges within the online antics of actor Channing Tatum and even cross–generational content, with voguing references appearing in the recently released,

Gen–Z oriented Hulu series Adults

While modern ballroom culture originated within Black and Latinx LGBTQ+ communities of Harlem, N.Y. in the early ’70s, it eventually found its way to Philadelphia 20 years later, allowing for a different kind of emergence— the kind sparked by hungry upstarts like local voguing legend Alvernian Davis.

In the ’70s, Alvernian Davis, known then as Alvernian Prestige, attended a ball in the capital of ballroom culture: Harlem. The events that transpired that night prompted the formation of House of Xavier, led by Davis at the age of 18, a stark contrast to most other Philly ballroom house parents, who tended to be anywhere in their late 20s to 30s. Although disagreements with house sponsors were a catalyst for the eventual disbandment of House of Xavier, the newly founded House of Prestige would be Davis’ next challenge at the behest of a crush, Michael Brown (better known then as Mike B). This venture proved successful, as the house went on to become one of Philly’s premier ballroom houses.

This story is only one of many. While ballroom centers competition, it thrives primarily on a communal sense of belonging, found abundantly within ballroom cultures across

the globe, especially due to its queer roots.

Queer communities have often been at odds with the state of the world. The appearance of HIV/AIDS in the ’70s and ’80s was one such conflict. In a time where prejudice and health challenges tore through a community already ravaged by the continually oppressive practices and policies of Frank Rizzo, a commissioner of the Philadelphia Police Department in the late ’60s, trailblazers like Davis provided safe spaces and created a milieu for unhindered creative expression.

The history of ballroom culture in the United States tells us a few things, of which the most important is perhaps the vitality of familial connection. Those on the fringes of an unrelenting society rarely find spaces that are safe, loving, supportive, and stable: This is a legacy that has persisted throughout history. Among the queer community, many have turned to prostitution or drugs for some form of community, and this has continued with contemporary alternatives coming in the form of sites like OnlyFans.

As a choice and expression–centered alternative, ballroom culture provides safety and security in many important forms. Ballroom houses often provide members with a roof over their head, as well as food and security from

the dangers of living on the streets. Members of the ballroom community reveal that ballroom culture then gave those who participated three important things: financial incentive in the form of cash prizes—a means to live, creative expression—a way to survive, and a chance at fame—a chance to thrive.

Generally, it’s surprising to see viral moments retain a lot of their history and legacy, but this is something that can certainly be said for the ballroom culture of the ‘70s. The contemporary scene is much larger, seeing as participants now navigate a tech–centric world with more exposure and more ease of convenience. Collaborations such as the ever–famous Madonna “Vogue” music video and the smash–hit series RuPaul’s Drag Race have likewise exposed ballroom culture to a wider range of people than ever before.

Wanya Allen is a member of the House of Unbothered Cartier and an avid member of the

Philly ballroom scene. Despite being a longstanding member, he is still relatively new to Philly’s “kiki” scene, a ballroom subculture that mirrors the “mainstream” most are familiar with, but on a more regionalized scale. Allen participates under the ballroom pseudonym “Wanda,” a name gifted to them by their house parent.

Allen's story stands as a quintessential example of contemporary ballroom culture and the environment it fosters. “As someone who’s black and gay,” he starts, “I was not accepted by my family. So ballroom was my safe haven to be who I wanted to be and live my life as me.”

Though this story is not wholly unique within the scene, that fact does not detract from the severity of its effects on the individual. He emphasizes that “a lot of us just want to feel loved, accepted, and at home. And a lot of us want that feeling of having a parent and having family to look up to. Because honestly, if it wasn’t for ball-

room, I probably wouldn’t be as confident as I am, or the individual that I am.”

Growing from the strains of frayed family relationships due to queer identities and having a “found family” within the ballroom scene in the form of housemates, house parents and elders, and fellow competitors is the classic story within the ballroom scene—it operates as a vehicle for an unapologetic and encouraging love. But that’s not the only way to get into ballroom. Drew Clarke, known in the scene as “Wally,” is a two–time Legend in the “All–American” and “Runners With a Twist” iterations of ballroom, and the current facilitator of the Rotunda’s (almost) weekly communal voguing sessions. Having previously been a part of such houses as the House of Unbothered Cartier and the House of Ninja, Clarke now stands as a pioneer in the Philly ballroom scene, being one of few to host regular balls.

Clarke’s story highlights another major tenet

of ballroom: creative expression. As Allen mentions, “It is really all about creativity, from your effects to your performance. … We create our looks using our way of how we see something.”

While attending Virginia State University, Clarke was part of an urban modeling group named Urban Couture. He progressed very quickly, teaching his own sessions by the end of his first year. Some friends of his involved in ballroom culture first introduced him to it, but he was unreceptive. This changed, however, after being stuck at home one Christmas break with his modeling “brothers and sisters.” Hours of scrolling through voguing videos together turned to fun sessions in the home, which in turn became an online presence that was enough to earn a practice session with the esteemed House of Ninja. Clarke now finds himself in the House of Gianni Versace.

Clarke is also a key part of a continuing movement to make ballroom more accessible

to the people of Philadelphia, and the driving force behind these efforts has been his relationship with a local concert and community engagement venue, The Rotunda. This began in 2021 and 2022, when Clarke reached out to house director and liaison between Penn and The Rotunda Gina Renzi. After communications, the two have blocked out most Tuesdays since, and the time is now reserved for community ballroom efforts, such as house practices and (almost) weekly voguing sessions that are open and free to the wider Philly community, overseen by technician “Stro.” This particular endeavor points to a potential next step in Philly ballroom culture—increased community efforts.

As an event organizer and Hall of Famer hopeful, Clarke notes that perhaps the biggest challenge to the ballroom community now is the lack of wider community support. Difficulties arise in trying to secure diverse and consis-

tent venues for balls and practices, as well as general accessibility to the craft.

Yet, ballroom is arguably at its most influential state, existing and operating on a global scale. The popularity of aforementioned shows, such as RuPaul’s Drag Race and POSE, have seen ballroom talents become stars with significant—and culturally groundbreaking— influences in mainstream pop culture. Still, their hold on their critical values is highly emphasized.

Philly ballroom definitely has space to grow, yet that only lends to its exciting nature. Community has been and will always be a part of the culture; The Rotunda’s involvement in the community stands as a testament to that. With a continued consistency and welcoming presence, Philly ballroom continues to spin and dip through strobing lights and bumping music, right around the corner of the street. k

The Birds 34TH STREET PRESENTS

Everyone Care If We’re Having Sex?

Benito

Why Does Everyone Care If We’re Having Sex?

The voyeuristic obsession with Gen Z’s sex lives

BY KATE CHO

Design by Insia Haque and Jackson Ford

rent discourse, our lack of it. You’d think Gen Z was either too traumatized to touch each other or too busy role–playing with artificial intelligence to have a real libido. In 2018, The Atlantic reported on what it calls a “sex recession” occurring among young adults following a 14% drop in high schoolers having sex, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. A new moral pan-

ic emerges—older generations are suddenly no longer concerned that young adults are having too much sex, but rather that they

The sex panic has rebranded itself: It is no longer about abstinence rings or purity balls, but about “liberation,” “empowerment,” “hypersexuality,” “femcels,” “healing,” and TikToks about “why I stopped having sex.” Everything is either a warning or a TED Talk.

The discourse itself has become more voyeuristic than anything on Pornhub. Generational predecessors treat Gen Z like a single organism: one hive mind of prudish, traumatized, overly online freaks who either

can’t get laid or don’t want to. As a flurry of articles floods front pages, it seems the older generations can’t help but obsess over what exactly Gen Z is or isn’t doing in the bedroom.

In The Society of the Spectacle, Guy Debord argues that modern life has replaced direct experience with images and representations. In other words, we don’t even care what happened—we care how it looked. Sex, like everything else in our lives, has been flattened into his concept of spectacle. It’s no longer private, or even particularly transgressive—it’s just content. It’s romantasy becoming one of the top–selling literary genres

and asking, “BookTok girlies, what’s the spice level in this?” In a world of OnlyFans, “girlbossing,” polycules, “ethical nonmonogamy” explainers, and kinks as personality traits, the new taboo is ambivalence. You can be queer, kinky, abstinent, hypersexual, traumatized—but you can’t just shrug. You can’t just not know. There has to be a reason, and everyone, it seems, is desperate to diagnose it.

We’ve branded even our disinterest. If you’re abstinent, it has to be aesthetic—Catholic coquette, clean girl, Lana Del Rey core. If you’re into sex, it’s a whole identity package: slutty but responsible, hot but healing, always in control. Even hookups have to come with a lesson. You need a takeaway to justify the risk.

We’ve lost the space for chaotic, uninterpretable sexual behavior. But sex isn’t always narratable. Roland Barthes writes in A Lover’s Discourse that the minute we try to speak about love, we estrange ourselves from it. Intimacy collapses under analysis. It becomes performative, theoretical, and uncanny. The more we try to capture it—the longing, the mess, the “I don’t know why I want him”— the more artificial it starts to feel. Sex works the same way. The more we explain it, the more it slips. And yet here we are, turning everything into a monologue. Into storytime. Into a trauma plot, or a kink diary, or a thread about how our ex gave us a UTI and daddy issues.

In a world where “He rawed me and I still can’t tell if I liked him” is both a meme and a trauma disclosure, we’ve turned sex into a mirror held up to ourselves. We’re spectators of our own lives. We don’t experience sex—we post about experiencing it. We turn it into proof that we’re hot, healing, complicated, interesting. And those people who are having the sex lives that Boomers suddenly seem convinced we should be having—casual, consistent, whatever—never talk about it. Not because they’re ashamed. Because it’s enough to just live it. It doesn’t need to be posted or packaged. It’s not for the gaze.

And then there’s Byung–Chul Han, who writes in The Transparency Society that in a culture obsessed with openness and overexposure, secrecy and ambiguity become radi-

cal. Ambivalence becomes resistance. What isn’t explained, shared, or optimized becomes threatening. Silence becomes power. He’s right—and nowhere is that truer than with sex. If you’re not narrating your hookups or labeling your dry spell, people assume something’s wrong.

But sometimes, there is no label. No story. Sometimes you just are. You sleep with someone, and it means nothing. Or it means something, and you don’t want to talk about it. Or it means something different on Wednesday than it did on Saturday. That’s not confusing. That’s life.

If there’s any kind of sexual liberation worth protecting, it should include the right to say nothing.

Romantasy and smut culture, in particular, sell us what Lauren Berlant would call cruel optimism—the belief that if you’re just hot enough, just good enough at setting boundaries, just healed enough to let the right dom touch you, then sex will finally click into place. You’ll be fulfilled. You’ll have a plot. But for most of us, sex isn’t a breakthrough. It’s not a resolution. It’s punctuation.

Even the “feminist” narratives—your Fleabags, your Emerald Fennell productions—still insist that meaning comes from not having sex. From learning to withhold. From rerouting desire into grief or growth or God. The opposite end of the same stick. Sex must break you or heal you. Euphoria and Saltburn just scream it louder.

In our increasingly pervasive culture, it feels as though there is no room in it for girls to just have sex. No room for the girl who enjoys it and doesn’t post a close friends slideshow. No room for the girl who wants it sometimes and shrugs it off other times. She’s not traumatized enough to be tragic.

Not horny enough to be a slay. She’s just living—and that doesn’t sell.

NPR defines “femcel” as “girls and women who are celibate, either voluntarily or involuntarily.” But that makes no sense. The whole term “incel”—involuntary celibate—is defined by not having access to sex despite wanting it. It’s about entitlement, resentment, and exclusion. Voluntary celibacy is literally the opposite of that.

The standard is stricter for men. A guy isn’t considered an incel unless he’s failing at sex. But a woman can be called a femcel even if she’s just opting out. The word stretches to include anyone who’s celibate at all—by choice, by circumstance, by boredom, by disinterest. There’s something quietly misogynistic and misandrist about that. It assumes men will always want sex, and if they don’t get it, they’ll become dangerous. But women? If they’re not having sex, it must be part of some pathology—repression, pick–me syndrome, performative tradness, a trauma response. The language builds in the assumption that women must always be in relation to desire—even when they’re saying no.

People who are genuinely content with their sex lives—whether it’s frequent, infrequent, monogamous, chaotic, or barely happening—usually don’t talk about it all the time. Not because they’re ashamed, but because there’s nothing to prove. Their intimacy isn’t for audience consumption. It’s private, not in the romanticized, candlelit sense, but in the nonperformative sense. It doesn’t need to be explained, aestheticized, or used as narrative currency.

We’ve built a culture where sex has to be explained, branded, or turned into content to be considered real. And if you’re not doing that—if you’re not sharing, processing, oversharing—people assume you’re ashamed or repressed. But maybe the refusal to narrativize isn’t a lack. Maybe it’s a boundary. Maybe it’s resistance.

There’s a difference between secrecy and privacy. Between repression and disinterest. Between being broken and just not giving everyone access. And if there’s any kind of sexual liberation worth protecting, it should include the right to say nothing. H

Are You a Freak in the Streets?

Trust Street, this is not a bucket list!

q 1. Crushed on someone that lived on your floor

q 2. Gone a date with your Penn Marriage Pact

q 3. Skipped class to go on a date

q 4. Joined a club to be closer with your crush

q 5. Had class with someone you ghosted

q 6. Sexiled your roommate

q 7. Had a DFMO at a party

q 8. Looked up a crush on Penn Directory

q 9. Friend–cest ruined your freshman friend group

q 10. Broke up during finals week

q 11. Seen your professor on a dating app

q 12. Breakfast at Hill as aftercare

q 13. Bought condoms from “Grommons”

q 14. Acquired club merch you are not a part of via a hookup

q 15. Dodged someone on Locust Walk that you hooked up with

q 16. Used LinkedIn as a dating app

q 17. Got in a relationship during NSO

q 18. Been walked in on

q 19. Met the parents before you defined your situationship

q 20. Ordered Plan B through the Wellness at Penn vending machine

q 21. Met someone on Sidechat

q 22. Showed up to class with hickeys

q 23. Cheated on your long–distance relationship

q 24. Gone on a first date at Smokes’

q 25. Hooked up with someone else’s date at a date night

q 26. Hooked up with your TA

q 27. Hooked up in exchange for help on your homework

q 28. Hooked up with someone in all four undergraduate schools

q 29. Lived with a situationship

q 30. Created a dorm guest pass for a hookup

q 31. Masturbated while your roommate was in the room

q 32. Hand stuff in a Huntsman GSR

q 33. Got engaged in your senior year

q 34. Sex under The Button

Come As You Are

The Struggle To Disseminate Sex Ed on Campus

BY NISHANTH BHARGAVA, SOPHIA MIRABAL, AND ANISSA T. LY

or many, the words “sexual education” often bring to mind a stuffy high school classroom—condoms on cucumbers, Googling STI symptoms, your gym teacher sitting you down to talk about “growing hair down there.” But it’s in college that these early lessons truly bear fruit. On campuses, sex ed morphs into something else entirely. Debriefs with roommates, whispers at parties, and Sidechat discourse become informal kernels of knowledge, filling in vast gaps left by inadequate high school curricula.

Design by Insia Haque and Jackson Ford

A 2023 report by The Daily Pennsylvanian found that 68.2% of Penn students consider themselves “sexually active”—so it’s up to the University, both students and administrators alike, to ensure equitable access to the knowledge and resources for healthy sexual practice on a college campus. At Penn, informal education is supported by both institutional resources and student–led initiatives, greeting a student body that arrives at very different starting points: Some undergraduates are schooled in abstinence–only programs, others with comprehensive curricula, and many international students have little to no prior exposure to pronounced sex education. They carry with them, consequently, the stigmas, silences, or overexposures of such systems.

This variation is hardly surprising considering how fragmented sex education is before college. In the United States, high school courses require, on average, just 6.2 total hours of instruc-

tion on human sexuality—the specifics of which are decided entirely at the state and local level. As a result, curricula differs greatly, from states like Oregon—which mandates annual instruction on STIs, contraceptives, and gender/sexual diversity to all middle and high school students—to those like Indiana—which does not require any sex ed and pushes schools that do teach the subject to encourage abstinence and display animated videos of “fetal development.” Access to sex ed is further complicated by the “opt–out” clauses many states have in place, which allow parents to remove their children from classes if they feel like the class content is inappropriate or objectionable.

That patchwork is striking enough within the United States. For international students, the contrast can be even sharper. Given that Penn’s undergraduate schools draw from more than 100 countries, the disparities are just as stark across international borders as they can be across state lines. Rebecca Lim (W ’27), grew up in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia. Coming to Penn, she couldn’t help but find it absurd that other students would describe lack of space for open dialogue when, back home, any posts that her nonprofit, the Noeo Project, wanted to published about sex ed had to undergo several rounds of screening. “In the U.S., everyone is empowered to talk about everything,” she says. “There is less red tape.” Back home, she describes public schools where sex ed is glanced over and kept within the bounds of science classes.

At Penn, student sexual–health initiatives don’t live under one single office or program. Instead, a loose network of resources operates to fit the needs of a particular aspect of campus life or segment of the student body. The Penn Women’s Center, the LGBT Center, and Wellness at Penn work to bridge the gap between the diverse backgrounds that converge on campus.

For many students, Wellness at Penn is the central entry point for student health concerns, immunizations and insurance waivers, medical care counseling, and more. In terms of sexual health on campus, Jackie Recktenwald, the director of Wellbeing Initiatives at Wellness at Penn, describes their goal in terms of “sexual citizenship”—equipping students with tools to navigate consent, pleasure, identity, and digital intimacy in a new environment. On paper, it appears more than sufficient. But these resources are only effective if students actually use them. While many students harbor a desire to destigmatize conversations around sex and sexuality, Wellness at Penn staff themselves acknowledge that it’s rare for students to reach out directly.

“I would say students are sort of hesitant to have these conversations in person. It’s very rare that we get someone who calls us on the phone to talk about sexual health,” says Recktenwald. “More often than not, they’re looking online or hearing from friends or going to resources that are not us.” The result is a strange juxtaposition: a student body that desires institutions built on a culture of access but is at times reluctant or unsure of how to utilize them.

Administrators hope to resolve this tension with Vibe, Wellness at Penn’s newly relaunched sexual health program. Formerly known as Declassified, Vibe is asynchronous and email–based, aiming to provide some relevant, of–

the–times insight into sexual health and culture at students’ own demand. It’s designed to reach students where they already are: on their phones, in their inboxes, searching for answers outside of University–designated hotlines.

“[Vibe] really runs the whole spectrum of sexual health and education. The first unit starts with basic anatomy, because we don’t know what level of education students have when they arrive to campus,” explains Wellness at Penn Director of Communications Mary Kate Coghlan. “Some of them are very well versed in sexual health and have a lot of experience with it; some have zero sexual health education or background. And so [you’re] really starting from the basics and then working your way through that, through communication and consent, and you know, all the different components of a healthy sex life and healthy sex education.”

The program contains a vast pool of resources. Later units cover overlooked topics in sexual health that appear frequently on forums where accuracy isn’t monitored, like a course on rough sex and choking that was added after research out of the University of Indiana flagged it as a growing area of emphasis. There are also sections on digital sexual health that reflect the realities of online relationships, dating apps, pornography, and even the rise of artificial intelligence companionship.

“Our philosophy is just providing sort of resource information up front,” says Recktenwald. “We know our students spend a lot of time online, right? We know a lot of people are meeting on apps. We know a lot of people are changing information there. And we want to just extend our general, educational approach to those places as well.”

But sex ed on campus is by no means limited to administrator–led initiatives. Penn Re-

productive Justice is one student organization with a two–pronged mission—making up for the paucity of education students receive before coming to Penn and offering access to resources that ensure students’ sexual health while they’re at the University. On the education front, PRJ’s programs for college students are tailored to fit their needs in an environment where many have their first sexual encounters—“[we talk about] different kinds of contraception,” says co–founder Annabelle Jin (C ’25), as well as “how to access them on campus, like through Student Health Services.”

Where PRJ really steps up, however, is in organizing direct product distributions. One of their most high–profile initiatives is the “Wellness Express” on the third floor of ARCH. Planned in collaboration with groups like the Trustees’ Council for Penn Women, the Undergraduate Assembly, and others, the Wellness Express is a vending machine that distributes condoms, Plan B, menstrual products, and other essentials to Penn students free of charge. Antoilyn Nguyen (C ’25), another of PRJ’s co–founders, argues that while access to information is important, it’s actual, physical products that are often most vital to students’ well–being.

“I could be super educated. I can do everything in the world that is about reproductive health,” they say, “But if I didn’t have the pads, tampons, menstrual cups, or underwear that I need to take care of myself when I’m on my period, then what does that mean for me?”

PRJ’s resource initiatives range from 24/7 anonymous Plan B deliveries—requested through an anonymous Google Form—to handing out dental dams and lube at their table on Locust Walk. “There’s no pressure, no stigma, just take it!” Antoilyn urges. “We love when people take our shit.”

While expanding access to physical resources forms the core of PRJ’s work, it’s these physical resources that have come under the greatest threat following recent policy changes by the second Trump administration. Though the White House hasn’t issued any explicit orders limiting access to contraception at the federal level, it has restricted the use of Medicaid funding to pay for elective abortions and reinstated the Global Gag Rule, preventing any foreign organizations that offer or consult on abortion services from receiving any assistance from the federal government. Moreover, at elite educational institutions across the country, Donald Trump (W ’68) has shown willingness to weaponize federal funding to browbeat universities into compliance with party politics. It’s a threat that Penn has cowed to before, going so far as to redact the records of transgender swimmer Lia Thomas (C ’22) to conform with the White House’s Title IX threats. Because student organizations on campus receive their resources from official University sources, a Trump order halting the ability of universities to supply gender–affirming or reproductive care would rapidly reduce students’ access to vital contraceptives such as Plan B.

One particular set of college sexual–health programs seems most at risk—those catering to LGBTQ+ students. From the beginning, the Trump administration has set its sights on dismantling “gender ideology”—the conservative byword for LGBTQ+ inclusion initiatives—that it claims has taken over campuses across the United States. While the administration’s most prominent actions in pursuit of this goal have been in cracking down on diversity, equity, and inclusion programs, Trump’s executive orders have also attacked various aspects of health care for LGBTQ+ Americans—a Jan. 28 executive order limits access to gender–affirming care for

minors under the guise of preventing “chemical and surgical mutilation,” while a more recent June rule from the Department of Health and Human Services prevents insurers from covering gender–affirming care costs as Essential Health Benefits for Americans of all ages.

The University has shown no lack of willingness to bow to the Trump administration’s commands before, having already planned cuts to inclusion initiatives at both University of Pennsylvania Carey Law School and Penn Medicine and banned transgender athletes from competition in response to White House pressure. Shifts to federal policy place Penn’s entire sexual–health ecosystem at risk. Official University bodies are bound to feel pressure from congressional scrutiny. Student organizations rely on University backing to get vital resources into the hands of those who need them most. Amid this pattern of ongoing compliance with the presidential administration’s regressive orders, can access to sexual health care on campus still be taken for granted?

Organized University resources like Wellness at Penn hold that their mission is to inform students about sexual health rather than tell them how to behave—whether that means providing medical care, counseling, or programs like Vibe. Recktenwald explains that the office aims to be a “jumping–off point,” emphasizing compliance with state policy rather than attempting to calibrate programming to the constantly shifting, often conflicting patchwork of national laws. The approach seems to mirror the University’s instinct for self–protection in an increasingly precarious policy environment: It’s better to present a buffet of resources than risk being accused of indoctrination, or worse, jeopardizing federal funding by running afoul of the White House’s whims.

But while University resources address material concerns at the present, they fail to directly address the anxieties many in the Penn community feel living in a policy–flexible environment. “I am not particularly worried about the access to reproductive care in my state,” says Angelie

Rodriguez (C ’27), an English major from New York. “But I am worried about the continued access of it in other states, where people might not be as open about forms of reproductive care. … I’m concerned about the continued production or availability of birth control, because it is so universally used, not only as a form of contraception, but also to regulate hormone imbalances for women.” These concerns are amplified by Penn’s LGBTQ+ community, who fear that further federal policy shifts could limit access to essential medical procedures. “As I transition, I know it’s going to get harder for me to get reproductive care,” says Ife Watts (C ’28). “I don’t have many friends on campus who are worried about reproductive care in the same way that I am worried about reproductive care.”

The vast patchwork of University offices and student–led initiatives can make sexual health on campus feel relatively well–supported. But graduation quickly severs those ties, dropping students back into the less fluctuating landscape of American health care policy. These fluctuations lead some international students to question whether to remain in the United States at all. “[There’s] a lot of volatility in U.S. policy,” says Max Nothacker (C ’27), an international student from Germany. “Volatility affects planning, and I want to plan my life.” While Penn may offer plenty of access to contraception or sexual–health information, the prospect of staying in a country where those rights and resources feel contingent on who occupies the White House remains unsettling.

Sex ed is more than a couple of middle school classes that are forgotten by graduation—it’s an effort that continues into college, and one that requires an active community to offer resources and knowledge to the students who need it. At Penn, the effort to create an open and welcoming environment is tangible. Beyond it, however, students are reminded that what they’ve learned matters little without the assurance that they’ll be able to apply their lessons freely and safely. H

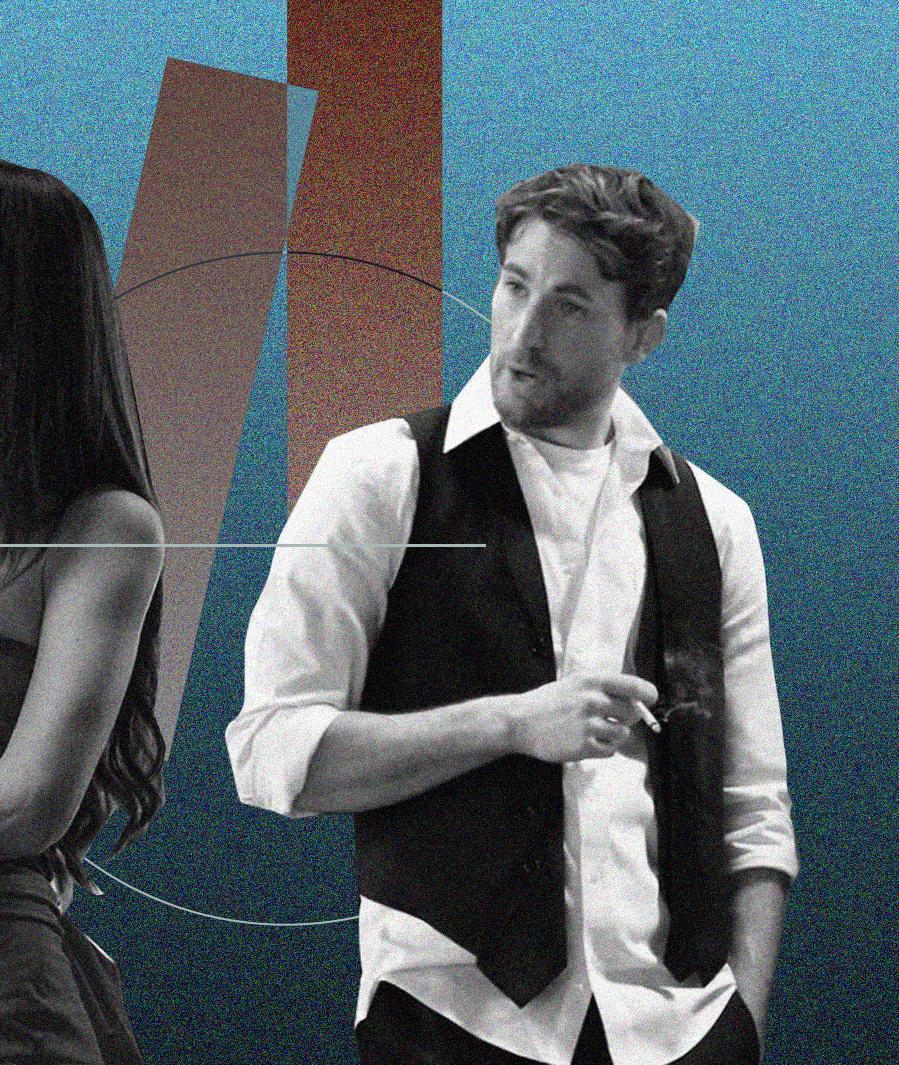

In Overcompensating, the Show Never Ends

Benito Skinner’s latest project pokes fun at people who are always performing, and the punchline is that it’s all of us.

BY SAMANTHA HSIUNG

Design by Kate Ahn

In most queer TV shows, the performance of straightness is merely a phase. A queer character might be in denial about their sexuality or reluctant to share details about their sexuality with others. They hide parts of themselves, presenting themselves in ways they think will be acceptable, and eventually come out—a moment of revelation framed as liberation. Overcompensating, the new queer comedy on Prime Video, refuses that neat resolution. It dismantles the idea

that coming out marks an end to performance, instead emphasizing that performance can permeate every aspect of a queer person’s life—extending far beyond just their sexuality. It makes it clear that overcompensating is not exclusive to queer experiences.

The show centers around Benny Scanlon (Benito Skinner), whom we first see hauling his belongings into his new dorm room at Yates University. His sister, Grace (Mary Beth Barone)—an upperclassman at Yates—has already

gained a strong social foothold and resents Benny for choosing the same college as her. We’re also introduced to Grace’s boyfriend, Peter (Adam DiMarco)—a self–proclaimed campus alpha who seems to only ever think about sex or parties, and Carmen (Wally Baram), a slightly nerdy classmate who spent high school in the shadow of her now–deceased brother and whom Benny quickly befriends on his first day of school. Imitating the macho personalities of the other guys at his college that

Unsurprisingly, the hook–up flops but initiates their beautiful friendship.

Overcompensating is the brainchild of Skinner—best known for his Instagram account @bennydrama7—where he built a strong following by performing caricatures of celebrities and pop–culture archetypes. The first version of Overcompensating debuted in 2018 at the New York Comedy Festival as a stand–up comedy skit about his efforts to remain in the closet while at Georgetown University—Yates’ real–life counterpart.

Like Skinner’s online Instagram persona, the world of the show is replete with caricatures. Every character is a familiar archetype lodged in Gen Z’s collective consciousness—turned up to the max. The joke is in the exaggeration, but the exaggeration also becomes the show’s scaffolding; within the world of Overcompensating, characters become legible to one another through these known stereotypes, just as we, the audience, use those stereotypes to make sense of what we’re seeing.

These sorts of exaggerations give way to the concept of overcompensation as the central node of the show, especially for Benny, who masks his queerness by performing hyperstraightness—throwing parties, tossing out “no homo” jokes, and calling every man he sees a “dude” or “bro.” He brags to his new college crew about hooking up with Carmen, lies to his parents about joining the rowing team so they’ll still see him as the athlete he was in high school, and constantly shapes himself to match an idealized perception others may hold. Skinner even plays Benny’s overcompensating moments with a deliberate stiffness to drive the point home—that Benny is bad at pretending.

The repetition of the exaggeration

we can hear the word “dude,” phrases like “seal the deal” (in reference to sex), or sentences like “I … fucked her” (I will leave the blank to your imagination) in domino–like succession.

But it’s that very exaggeration that makes the moments when Benny breaks through his mask all the more incisive. These moments form the core of Benny’s friendship with Carmen— like when Benny apologizes to Carmen for lying to other people about hooking up with her, and when Carmen comforts Benny after his heart is crushed by his first male crush in college. Each scene momentarily punctures the relentless performance that Benny had tried so hard to keep up, and they stand among the show’s most meaningful moments.

In many queer coming–of–age shows, the main character often follows a familiar arc. Cracks in their performance of straightness keep deepening until their mask finally drops for good. The entire show generates momentum toward the moment of coming out, treating it as the central point of the plot, and the following episodes or further seasons may cover the aftermath of the revelation: the liberation of having come out, the exploration of different romantic relationships, the navigation of new dynamics with friends and family, and the satisfaction of being able to settle into a more open, authentic sense of self. Heartstopper, the 2022 Netflix breakout hit, is a textbook example. Its first season is anchored in Charlie’s journey of self–acceptance and Nick’s journey of coming out, and its latter two seasons are devoted to the joys and challenges of life after coming out.

But Overcompensating makes a sharp break from most queer coming–out narratives. Even after Benny comes out

to Carmen and a few others, he still doesn’t stop performing. Before coming out, he had overcompensated for his queerness by mimicking the behavior of an uber–straight jock. After coming out, he overcompensates in the opposite direction by leaning into the role that Carmen assigns to him as her gay best friend, or “GBF.” He curates his behavior to match his new role as a GBF by going on Grindr dates, watching RuPaul’s Drag Race with Carmen, and letting her teach him about queer history.

Queer or not, everyone is always putting on a performance of who they think they should be.

However, Benny’s adoption of this new role does not indicate that he is done hiding. He continues to conceal other details about his life to project the most idealized version of himself to other people. He lies to Carmen about having left Flesh and Gold—Yates’ elite secret society they were both invited to rush but from which she was rejected— even though he hasn’t, protecting both his fraternity boy persona and Carmen’s feelings. Around other Flesh and Gold members, he acts as if he isn’t friends with George—a queer activist at Yates whom Benny had befriended when he was struggling to understand his sexuality. Coming out doesn’t free Benny from the need to shape himself for others; rather, coming out creates a new set of expectations that Benny feels the

need to fulfill. This concept of overcompensating doesn’t just apply to Benny; it applies to every character in the show. And that is perhaps the most important critique made by the show—that queer or not, everyone is always putting on a performance of whom they think they should be. While rushing Flesh and Gold, Carmen flattens her personality around the members and even lies about not being lactose intolerant to attend a dinner with them. Grace used to be a grungy girl in high school who loved My Chemical Romance, but she shifted her personality to that of a stereotypical, straight white girl after dating Peter. Peter acts like he owns everything in the world in front of Grace and his friends, but deep down, he is insecure about his socioeconomic status and lack of job prospects. In each case, the gap between their private selves and public performance is vast, and every character is sculpting a version of themselves for others just to fit in. By pushing these personas to absurd extremes, Skinner shows just how much effort it takes to keep them intact. Sometimes, though, these performances do slip. When Carmen visits Benny and Grace’s home over Thanksgiving break, we see flashes of Grace’s old self. With Carmen’s encouragement, she sings “Welcome to the Black Parade”—a song by My Chemical Romance—at a gathering in front of all the boys who made fun of her in high school. Grace’s reversal into her past self is not a coming out in the traditional sense, but it functions quite similarly, as she exposes a hidden part of herself that she had been working to keep sheltered away from the world. By showing that these moments of self–revelation happen across all types of people, Skinner frames “coming out” as a universal concept—one that isn’t just about sex-

uality, but also about the ongoing negotiations that everyone might have with their own identities.

By the end of the show, Benny catches Carmen betraying him in the worst of ways (no spoilers). A verbal war breaks out between them, and the fight continues escalating until Carmen pointedly accuses Benny of wanting to sleep with everyone’s boyfriend. Grace walks in at the pivotal moment, and the show ends. We’re tragically left on a cliffhanger. This scene, however, is not the triumphant, cathartic moment of truth that is often promised in queer narratives. Rather, it is a reminder that coming out can be abrupt, messy, and even imposed by others. Benny is now out to his sister, but not on his own terms; he is stripped of every bit of control that he had maintained throughout the season. Along with cliffhangers, we’re also left with lingering questions that drive home Overcompensating’s thesis: What new expectations will Benny have to grapple with in the upcoming season, now that his sister knows that he is gay? In what new ways will Benny be overcompensating or performing a different version of himself now that more people know about his sexuality?

In the turbulence and chaos of college, perhaps everyone performs a fake version of themselves—feigning interest in clubs or classes that they secretly dislike, exaggerating how happy they are in a relationship, or pretending to do well when they’re not. All the world, as William Shakespeare says, is just a stage— except in Skinner’s fictional world of over–the–top characters, no one seems to want to step off. But maybe the most honest, most refreshing thing is for a comedy to admit that—that maybe performance isn’t just a temporary act on the way to an “authentic” self. Maybe the performance is never just a phase. It’s the whole point. H

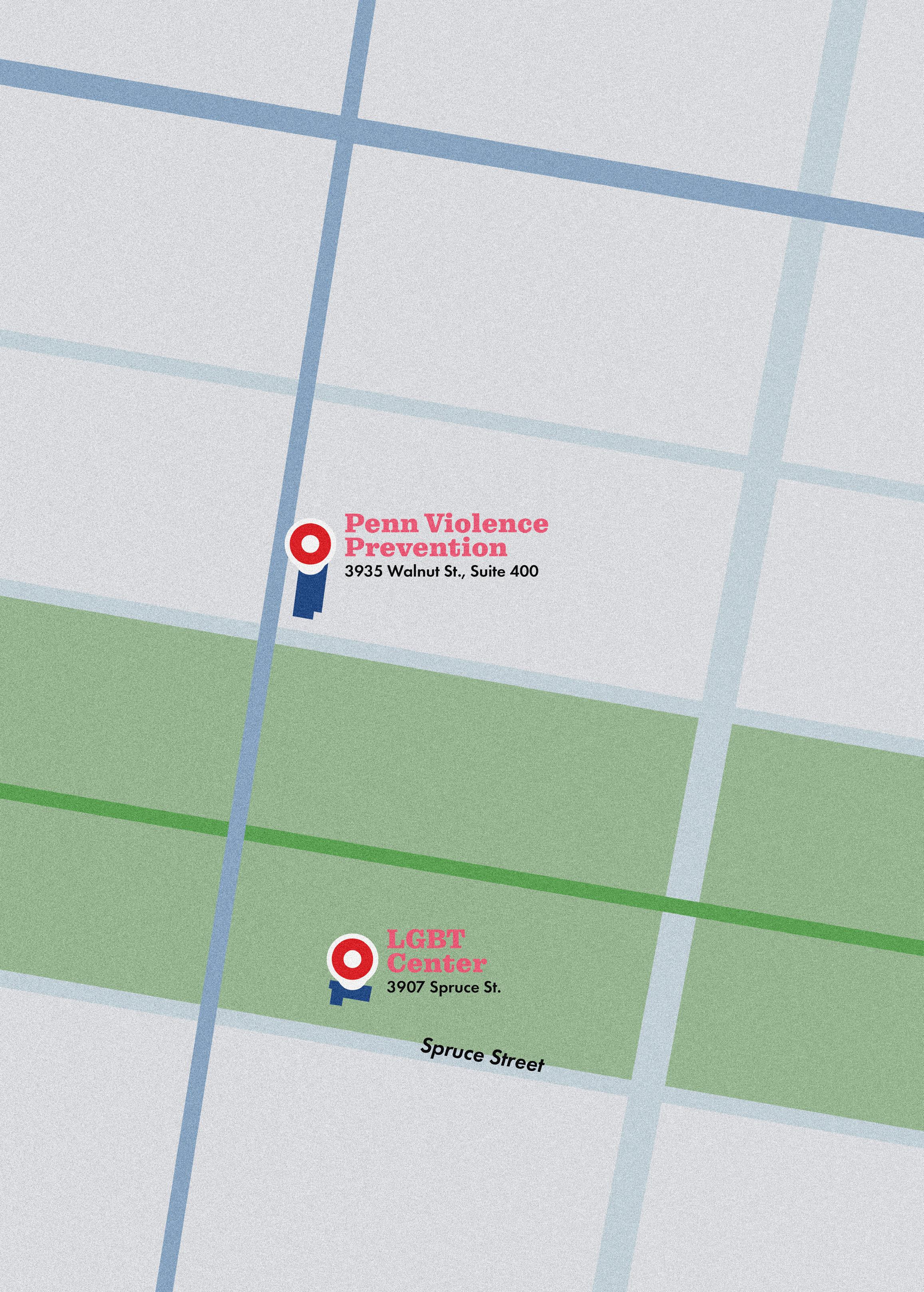

The Ins and Outs of Sexual Health at Penn

From supportive communities to STI testing sites, Street is rounding up resources.

BY SARAH LEONARD

Design by Chenyao Liu

For many students stepping onto a college campus for the first time—or for any one, frankly—sex can be a lot. There is both the new opportunity to explore this formerly elusive world and a sudden thrust into the very real emotional and physical implications that come with sex. Induced shame, forced ignorance, and a lack of access to information and resources can lead young adults to feel overwhelmed about entering this new stage of their life. Navigating the world of sex health and reproductive justice on campus and in the city can be confusing—that’s why we compiled this list of resources for you.