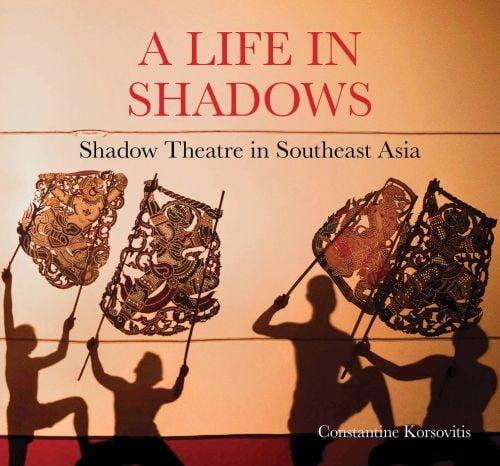

First published and distributed in 2024 by River Books Press Co., Ltd

396/1 Maharaj Road, Phraborommaharajawang, Bangkok 10200 Thailand

Tel: (66) 2 225-0139, 2 225-9574

Email: order@riverbooksbk.com www.riverbooksbk.com @riverbooks riverbooksbk Riverbooksbk

Copyright collective work © River Books, 2024

Copyright text © Constantine Korsovitis

Copyright photographs © Constantine Korsovitis, except where otherwise indicated.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or including photocopy, recording or any other information storage and retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publisher.

Editor: Narisa Chakrabongse

Production supervision: Suparat Sudcharoen

Design: Ruetairat Nanta

Previous page: East Javanese puppet master, Ki Surwed, cradles Anoman. Mojokerto, Java. 2017.

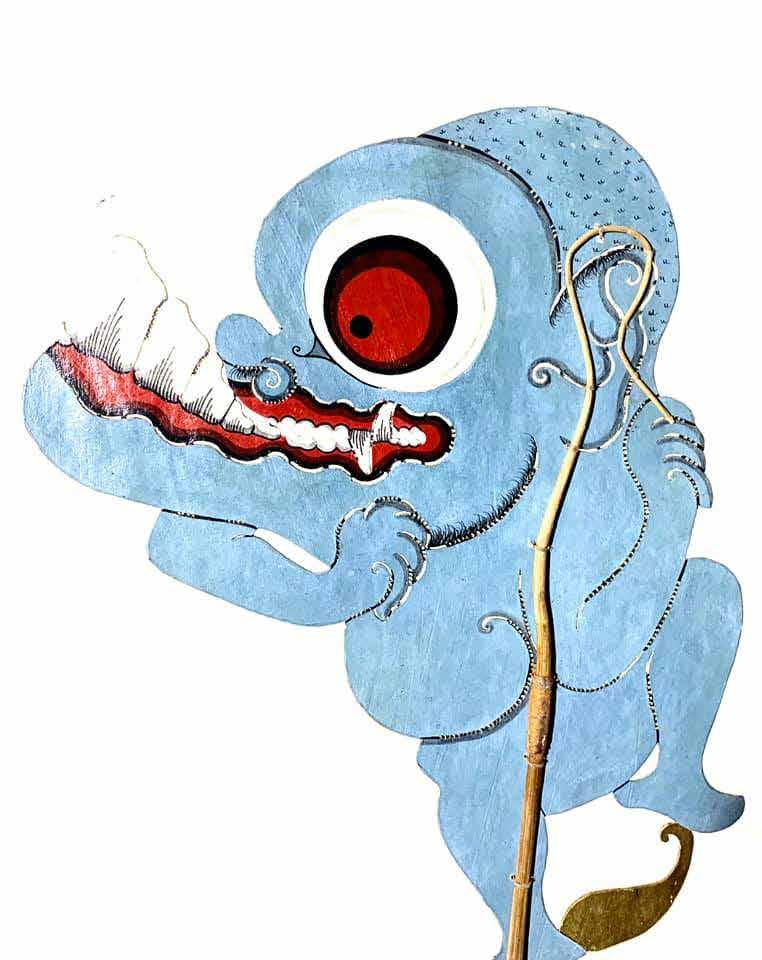

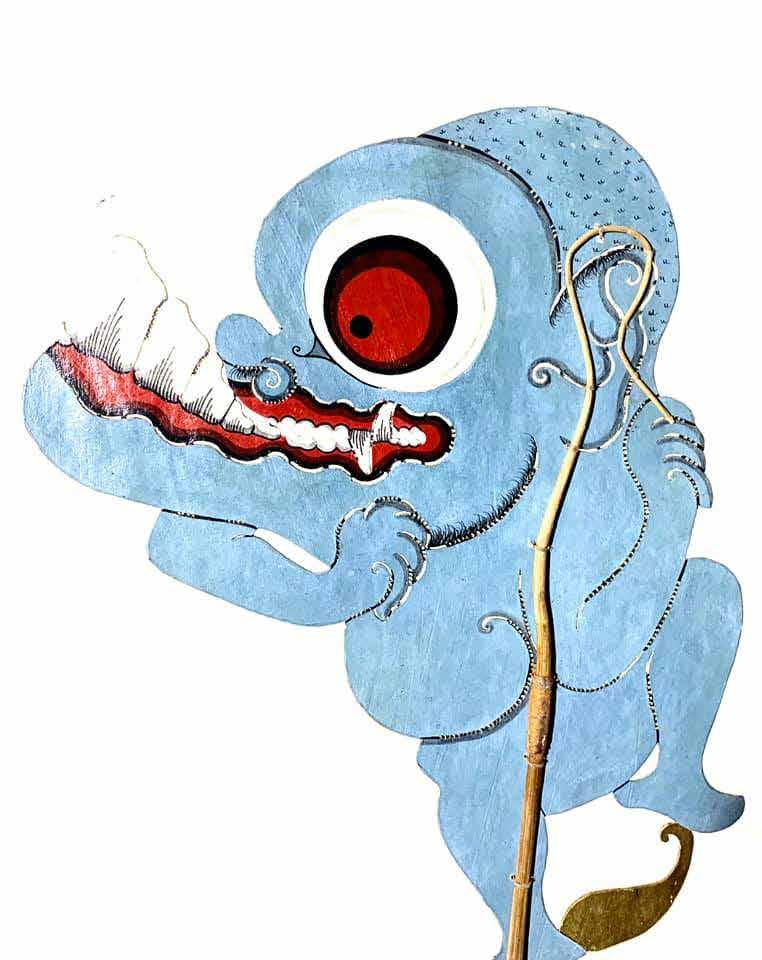

Opposite: Unnamed demon from the Kacirebonan Kraton in Cirebon, Indonesia, 2018.

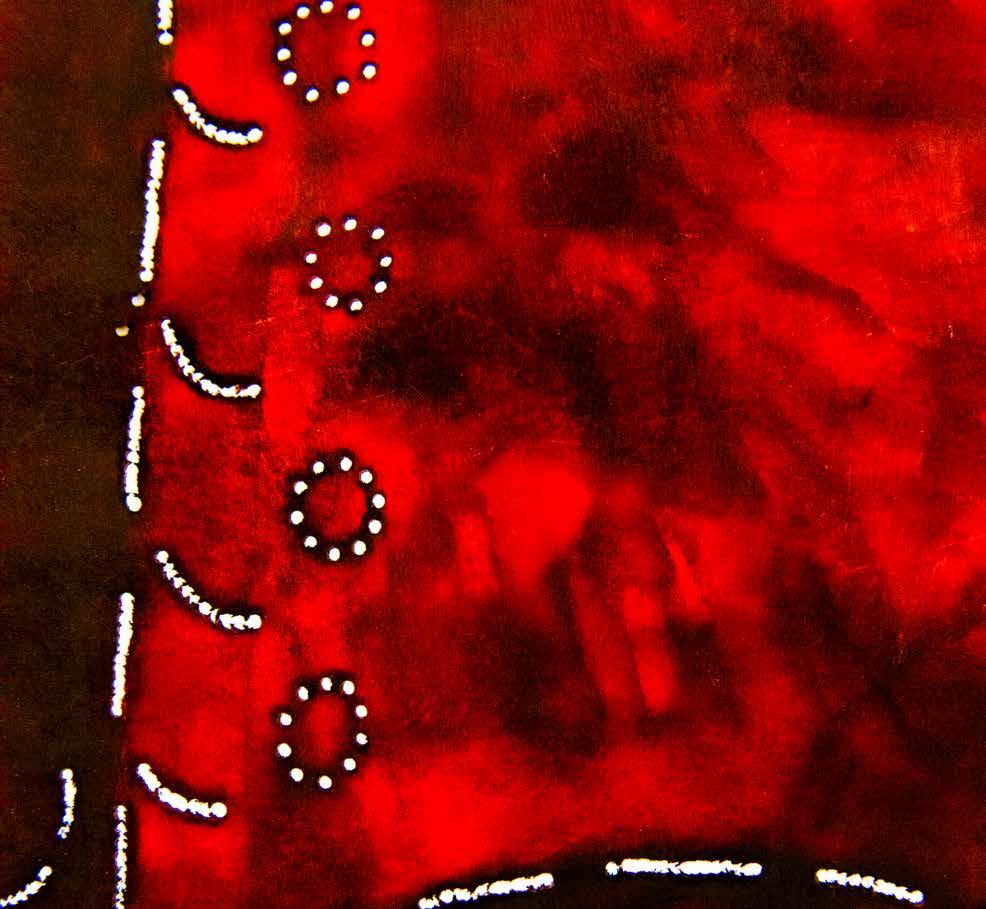

Opposite dedication page: Nang yai puppet detail, Kasem Bundit University Nang yai troupe collection, Bangkok, Thailand, 2018.

ISBN 978 616 451 084 5

Printed and bound in Thailand by Sirivatana Interprint Public Co., Ltd

The aftermath of the performance. Nakhon Si Thammarat, Thailand, 1996.

A musician playing the alto fiddle during a nang talung performance in Nakhon Si Thammarat, Thailand, 2003.

IntroduCtIon

Before us is a book filled with artful portraits of revered shadow-puppet masters and puppetry arts from Indonesia, Thailand, Cambodia, and Malaysia. From the large, magnificent shadow puppets of Thailand (nang yai) and Cambodia (nang sbek thom) manipulated by numerous standing puppeteers, to the deeply spiritual wayang lemah daytime ceremonies in Bali carried out by priests, to the spectacular multi-faceted productions of wayang kulit purwa by superstar dalang in Central Java, the photos in this book offer readers a gateway to the inner lives of the performers.

Some Historical Musings

The talented artists seen in these pages are the descendants of a lineage of shadow puppeteers stretching anywhere from a few centuries to more than a thousand years ago. Details and determining artefacts are few, such that the question of era and origin of various forms of shadow puppetry in Southeast Asia is highly debated. But we do have a few points of reference. One piece of physical proof is a copper plate inscription from the village Sangsang in East Java, dated 4 May 907 CE. A performance took place in which both the (shadow?) master (Galigi) and the story (Bhima Kumara) were named. If it was important enough to the commemoration of the event to name the performer and the story, it seems that the art form must have been well-established in 907. We cannot be entirely sure, however, that this inscription refers to a shadow play. However, an existing manuscript in Old Javanese by Mpu Kanwa from 1030 CE, Arjunawiwaha, does specifically refer to audiences weeping over the shadow-puppet images:

“For example, someone watching wayang puppets weeps, is sad, foolish and easily moved, though he already knows that it is only chiselled leather that moves and talks. This is like the man who is attached to the objects of the senses, even to the point of not recognizing that their true nature is unreality, and every form of existence is an illusion.”1

Fast-forward to the 1400s, there is an undisputed reference to performances of nang yai shadow puppetry in palace-law writings of King Ramathibodi I (1448-1488) during the Ayutthaya period in Thailand. Researchers believe that during the golden era of the Majapahit Empire (1300s-early 1400s) shadow puppetry may have travelled from Java to southern Thailand, or Siam, developing into two of the art forms represented in this book: nang yai (over-sized puppets) and nang talung (small-size puppets from the Phatthalung region). There are some, however, who believe that the appearance of shadow puppetry in Siam was an influence from travelling brahmans of India.

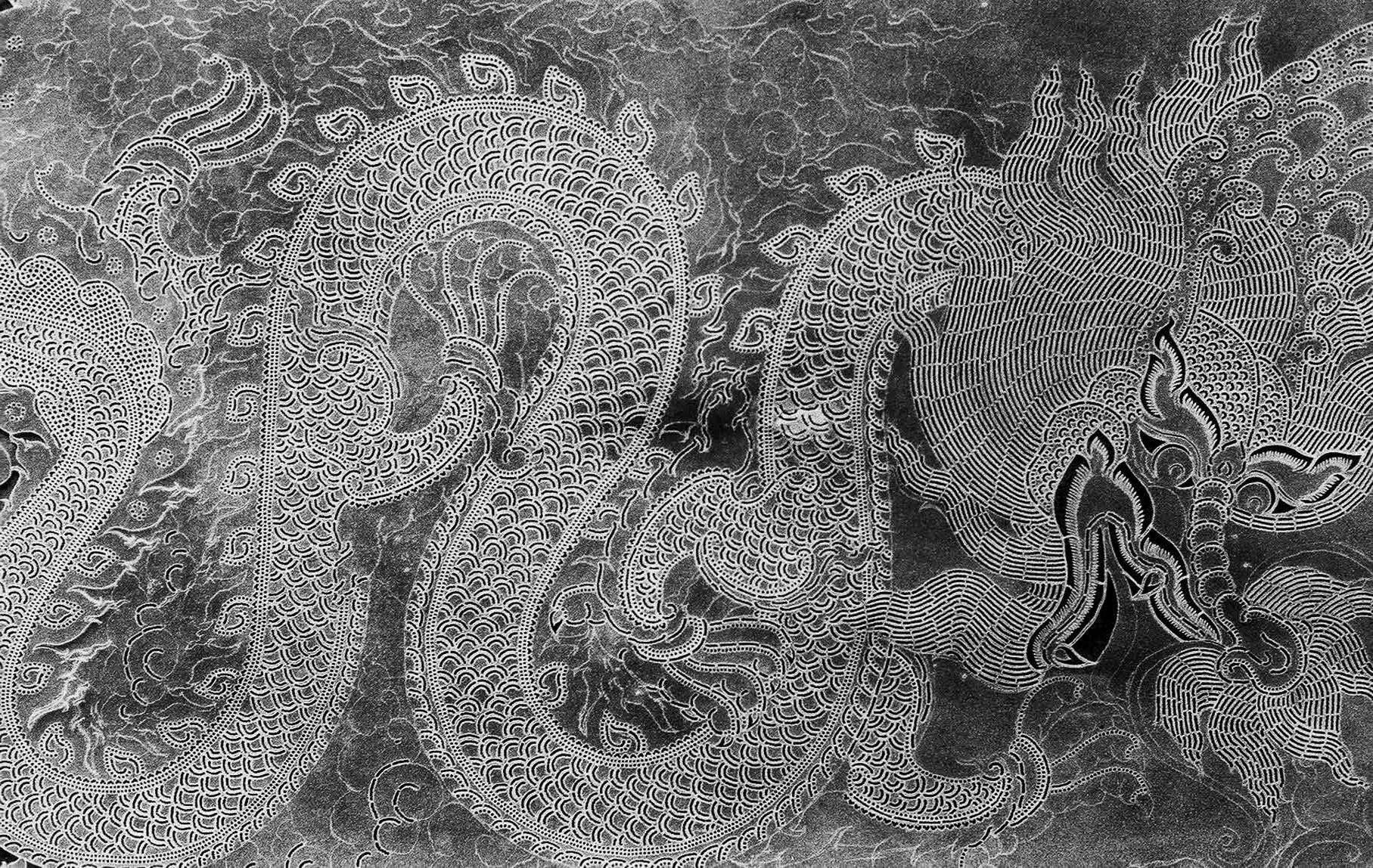

Opposite page: Nang yai puppet detail, Wat Sawang Arom Museum, Singburi, Thailand, 2016.

1 Arjunawiwāha by Mpu Kanwa, 1030 CE, translated to English by Stuart Robson from the Old Javanese (KITLV Press, Leiden, 2008), canto 5, stanza 9. This is the scene in which the God Indra, disguised as a travelling brahman in the forest, comes to test the meditating Arjuna on matters of esoteric knowledge.

Opposite page: Dragon in the making, Rong Jae, nang talung workshop, Nakhon Si Thammarat, 2016.

Above & below left: You first draw on paper, next on leather, and then you carve and colour it.

A musician playing the xylophone or ning nong, during a performance of nang talung in Nakhon Si Thammarat, 2001.

The Thai flute or klui is another important instrument in the performance of shadow theatre in Thailand. Nakhon Si Thammarat, 2001.

Opposite page: Nang talung performance by Siri, as part of the Harmony World puppet festival in Phetchaburi, 2024.

The Banyan tree or Pohon Beringin is perceived as the most important puppet of them all. The leafshaped puppet is used in the beginning and end of all Kelantanese puppetry performances.

Shadow theatre is about family. Malaysian master, Pak Miskon is pictured here with his son and grandchildren, who are all part of his troupe. Johor Bharu 2016.

Wayang kulit is about community. A music class conducted by Pak Miskon’s musicians, teaching the locals the sounds of the wayang. Johor Bharu 2016.

Right: All the tools of the trade.

At Setia Budia practice centre in Johor Bharu, 2016.

CK: In 1998 wayang kulit was banned in Kelantan. Please comment on this.

TN: The state government banned wayang kulit for a while in Kelantan because they claimed it has pre-Islamic roots. They don’t understand that wayang kulit has been adapted to our Kelantanese Malay-Muslim sensibility, and is not in conflict with Islam. We do not worship any wayang characters. They are characters of a story that we perform.

CK: Why is wayang kulit so important to the people of Kelantan?

TN: Wayang is part of the Kelantanese people. It reflects all the possibilities of our human character and the changing conditions of life. Through the old stories of Seri Rama, Sita Dewi, Maharaja Wana, and Hanuman, Pak Dogol, and other mythological figures, wayang kulit tells us about ourselves. Wayang teaches us about the world and everything in it. How to distinguish good and bad, but also that not everything is black and white.

CK: How does he prepare for a performance? Physically, mentally and spiritually.

TN: Before a performance, I prepare myself spiritually, mentally, and physically. I spend many hours thinking about the story and the characters I will perform. The old stories are part of me, they are alive in my memory. I enter that world, so that I can bring it to life when I perform.

CK: In what way has wayang affected your life?

TN: Because of my deep love for wayang kulit, it has become a part of my soul. I easily memorise and remember every story, every movement, every plot, every character and their genealogy. If there were no public performances, I would still perform wayang at home, even without an audience. I would call the wayang musicians to perform with me, to release my angin (inner wind, artistic temperament). Does he dream about wayang? I once dreamt about wayang when I was a teenager, but I can’t remember the dream. Now I don’t dream about wayang

Any regrets?

No regrets.

Everybody gets to help... Pak Nawi and members of the Pusaka wayang kulit troupe. Left to right... Irsyad Abdul Rahman (geduk), Syafiq Abdul Rahaman (gendang anak), Pak Nawi, Abdul Rahman Dollah (head musician, gendang ibu), Adilah Mohamed (troupe manager) and Pak Nawi’s wife, Mek.

One of the things that I wanted to find out and explore through my project was the impact of modern technology, politics, Islamic thought and philosophy on shadow theatre in Indonesia.

There are two schools of thought on Islam and wayang. One is that the Wali Sanga, the saints that spread Islam through Java, used wayang, therefore there is respect for it. The other school of thought is that wayang was not used and therefore the tradition

should not be respected. There has been censorship from the police and the government with regard to what you could say, especially in the post-Sukarno era. From 1965 onwards many dalang were imprisoned because of their associations with Lekra, which was affiliated with the Communist Party of Indonesia. In fact, you needed a letter from the cultural office to be able to perform before 1998.

Sinden are the female singers in a shadow theatre performance in Java. Wayang kulit performance, Ki Enthus Susmono, Tegal, 2016.

Wayang kulit peroformace by Ki Enthus Susmono, Tegal, 2015.

Love is in the air… Sbek touch performance by the Duk Roeun troupe. Siem Reap 2001.