—Marine Serre ontvangt de LVMH-prijs voor jonge ontwerpers.

—Marine Serre wins the LVMH Young Fashion Designer Award.

—À la première édition des Belgian Fashion Awards, le label Façon Jacmin reçoit le Prix du talent émergent.

—Tijdens de eerste editie van de Belgian Fashion Awards wint het label Façon Jacmin de prijs voor opkomend talent.

—At the first Belgian Fashion Awards, the label Façon Jacmin wins the Emerging Talent Award.

—Louis-Gabriel

Nouchi fonde une marque à son nom.

—Louis-Gabriel Nouchi richt een eigen merk op.

—Louis-Gabriel

Nouchi founds his eponymous label.

2018

—Exposition « It’s my OWN. An everyday fashion story » à MAD Brussels.

—MAD Brussels organiseert de expo ‘It’s my OWN. An everyday fashion story’.

—“It’s my OWN. An everyday fashion story” exhibition at MAD Brussels.

—Exposition « LOL La Cambre Mode[s] » au Musée Mode & Dentelle.

—In het Mode & Kant

La boutique STIJL a ouvert ses portes en septembre 1984 au 26 de la rue Antoine Dansaert à Bruxelles. Je vais commencer par la question la plus simple. Pourquoi ?

En fait, ça a été une décision très spontanée et intuitive.

Il faut comprendre qu’à l’époque, il y avait peu de choses en matière de mode à Bruxelles. La mode belge telle que nous la connaissons aujourd’hui n’existait pas encore. Les couturiers italiens et français dominaient le paysage vestimentaire.

Le centre-ville abritait Comme des Garçons et Crea, deux magasins de Jenny Meirens, et quelques boutiques plus modestes, telle la vitrine bruxelloise Danaqué, de Sandrina D’Haerre. Tout le reste était très commercial.

J’avais envie de découvrir de nouvelles choses et je me suis lancée dans ce projet dès que l’opportunité s’est présentée, par l’intermédiaire d’une amie qui possédait un magasin à Lausanne. Je ne connaissais rien à la mode mais j’avais étudié l’histoire de l’art. J’avais donc l’œil pour repérer ce qui était innovant. En 1984-85, j’ai découvert les Six d’Anvers grâce au concours de la Canette d’Or. Ils sont ensuite venus me présenter leurs collections respectives. Après STIJL femmes, STIJL hommes a rapidement vu le jour en 1985.

J’imagine que votre boutique a presque tout de suite rencontré le succès ? Qui était le client STIJL ?

À l’époque, STIJL était tellement singulier que les gens s’y rendaient par simple curiosité. Le magasin proposait bien plus que des vêtements. L’architecture intérieure était exceptionnelle, très minimaliste. La boutique

STIJL opent in september 1984 op nummer 26 van de Dansaertstraat. Ik ga met de simpelste vraag beginnen: waarom?

Dat was eigenlijk een heel spontane en intuïtieve beslissing.

Je moet begrijpen dat er in die tijd héél weinig aanwezig was op modevlak in de stad. De Belgische mode zoals we die nu kennen, bestond nog niet. De Italiaanse en Franse couturiers domineerden toen het modelandschap.

In de benedenstad had je Comme des Garçons en Crea, twee winkels van Jenny Meirens, en enkele kleinere boetieks, zoals het Brusselse Danaqué van Sandrina D’Haerre. Verder was alles ontzettend commercieel.

Ik had de drang om nieuwe dingen te ontdekken en ben in dit project gerold zodra de gelegenheid zich voordeed via een vriendin die een winkel had in Lausanne. Ik kende de mode niet, maar had wel kunstgeschiedenis gestudeerd, dus ik had een gevormd oog voor wat vernieuwend was. In 1984-85 leerde ik de Zes van Antwerpen kennen via de Gouden Spoel-wedstrijd. Zij kwamen hun collecties dan bij mij presenteren. Na STIJL vrouwen kwam snel STIJL mannen, in 1985.

Ik neem aan dat je dus vrijwel meteen succes had met je winkel? Wie was de STIJL-klant?

Omdat STIJL toen zo anders was, kwamen mensen specifiek daar naartoe, uit nieuwsgierigheid. De winkel bood meer dan kleding. Het interieur was ook zo uitzonderlijk, héél minimalistisch. Het werkte inspirerend.

STIJL opened its doors on 26 rue Dansaert in Brussels in September, 1984. I’d like to start with a simple question: how did it come about?

It was actually a very spontaneous and intuitive decision.

You see, at that time, the fashion offering in the city was very limited. Belgian fashion as we know it now didn’t exist then. The fashion scene was dominated by Italian and French designers.

In downtown Brussels, Jenny Meirens had two boutiques, Comme des Garçons and Crea, and there were a few smaller shops, like Sandrina D’Haerre’s Danaqué. The rest was mostly high street ready-to-wear.

I was looking for something new to do, and as soon as an opportunity arose, through a friend of mine who owned a store in Lausanne, I decided to open my own boutique. I didn’t know much about fashion at the time, but I’d studied Art History and I had an eye for innovation. I discovered the Antwerp Six in 1984 and 1985 through the “Golden Spindle” design contest and they subsequently showed me their collections. After opening the STIJL shop for women, I opened a men’s STIJL store in 1985.

I assume these met with success. Who was the typical STIJL customer?

At the time, there was nothing like STIJL in Brussels; people would stop by out of sheer curiosity. Also, it offered much more than just clothing. It had a deliberately very minimalist vibe; it was a veritable mine of inspiration!

Many Belgians didn’t subscribe to the glamorous styles of French and

Museum vindt de tentoonstelling ‘LOL La Cambre Mode[s]’ plaats.

—“LOL La Cambre Mode[s]” exhibition at the Fashion & Lace Museum.

—Le collectif GAMUT, composé de cinq diplômé.e.s de La Cambre, défile à Paris.

—Het collectief GAMUT, dat bestaat uit vijf oud-studenten van La Cambre, defileert in Parijs.

—The GAMUT collective, founded by five La Cambre graduates, stage a runway show in Paris.

—Ester Manas est lauréate de la dotation Galeries Lafayette au Festival d’Hyères et est invitée à concevoir une collection capsule pour le magasin parisien.

—Ester Manas wint de Galeries Lafayettebeurs op het festival van Hyères en mag een capsulecollectie voor de Parijse winkel ontwerpen.

—Ester Manas wins the Galeries Lafayette Prize at the Hyères Festival and designs a capsule collection for the Parisian department store.

—Giuseppe Virgone présente son premier défilé à Paris.

—Giuseppe Virgone houdt zijn eerste show in Parijs.

—Giuseppe Virgone

constituait pour beaucoup une source d’inspiration.

De nombreux Belges n’avaient aucune affinité pour le glamour français et italien qui dominait à l’époque. Un groupe de Bruxellois audacieux et individualistes voulait se démarquer et surtout faire table rase de ce qui était alors proposé. Cette identité était facile à définir. Mes clients se démarquaient dès qu’ils entraient dans la boutique. Ils étaient parfaitement conscients de leur apparence, et je pense qu’ils jouaient aussi de cette attitude distante. Tout cela était alors plus clairement délimité qu’aujourd’hui. Mes clients et moi poursuivions la même quête. Nous partagions une même vision esthétique.

Il s’agissait donc d’un large changement collectif dont vous faisiez partie ?

Exactement, et cela dépassait le cadre de la mode vestimentaire. Prenez par exemple le Beursschouwburg et le Kaaitheater, qui ont fait du quartier un pôle d’attraction culturel. J’ai toujours tenté de soutenir cette créativité qui m’entourait. Vers la fin des années 1980, plusieurs jeunes entrepreneurs ont ouvert leur boutique de mode ou de design dans le quartier, en proposant leur propre collection ou d’autres créations innovantes. Ce qui les unissait, c’était leur différence ; l’aspect exploratoire était toujours présent. Je pense par exemple à Kat, la boutique de vêtements pour enfants, mais aussi à Rue Blanche et à Johanne Riss, ou même au premier Pain Quotidien au monde. Plus tard, Annemie Verbeke est venue gonfler ces effectifs. J’aimais beaucoup être entourée de gens animés d’une même volonté.

Veel Belgen hadden geen affiniteit met de Franse en Italiaanse glamour die toen domineerde. Er was een groep mensen in Brussel, individualisten en durvers, die zich wilden onderscheiden en vooral tabula rasa maken met wat er al was.

Die identiteit was heel duidelijk te definiëren. Mijn klanten vielen op zodra ze binnenkwamen. Zij waren zich heel bewust van hoe ze eruit zagen en ik denk dat zij ook speelden met hun afstandelijkheid. Dat was toen veel duidelijker afgelijnd dan vandaag. Ik en mijn klanten waren naar hetzelfde op zoek. We deelden een bepaalde esthetische visie.

Het ging dus om een grotere collectieve verandering waar jij deel van uitmaakte?

Zeker, en dat was niet enkel in de mode. Denk maar aan de Beursschouwburg of het Kaaitheater, die van de buurt een culturele trekpleister maakten. Ik heb altijd geprobeerd die creativiteit rondom mij te steunen. Aan het eind van de jaren 80 begonnen ondertussen verschillende andere jonge ondernemers hun eigen zaak in de buurt, in mode of design, met eigen collecties of tot dan toe onbekend werk. Wat hun verenigde was dat het anders was, er was steeds een onderzoekend element. Dat was bijvoorbeeld de kinderkledingwinkel Kat, maar ook Rue Blanche en Johanne Riss, of zelfs de eerste vestiging van Le Pain Quotidien ter wereld. Later kwam ook Annemie Verbeke. Het was fijn om omringd te zijn door gelijkgezinden.

Je moet ook begrijpen dat die scene in Brussel heel klein was. Iedereen kende elkaar, we steunden elkaar.

Italian designers that dominated the fashion scene at that time. These customers were more daring and forward-thinking, looking for more personal styles that made a break with the past and they ultimately really wanted something fresh to stand out from the crowd.

It was a clearly identified look. As soon as they walked in the door, you could immediately tell who my customers were. They were very aware of their personal style and I think they liked playing up their uniqueness, which was much more striking than it is now. My customers and I were looking for the same thing. We shared a similar aesthetic vision.

Was this part of a broader, collective shift in which you played a role?

Certainly, and it was not only about fashion. The Beursschouwburg and the Kaaitheater, for example, turned the area into a cultural hotspot. I’ve always done my best to support that kind of creativity. In the late eighties, other young entrepreneurs opened fashion and design boutiques in the neighbourhood, selling their own collections or items made by little-known designers. They were different, and that brought them together; they shared the same desire for innovation. There was Kat, which sold children’s clothing, Rue Blanche and Johanne Riss, even the very first Le Pain Quotidien in the world opened here. Later, Annemie Verbeke moved into the area. It was wonderful to be surrounded by like-minded people.

You have to understand that the Brussels scene was a small one. We all knew each other and supported each other. I had met Xavier Delcour, for example,

presents his first runway show in Paris.

—Diane von Fürstenberg, née à Bruxelles, est faite citoyenne d’honneur de la Ville.

—Diane von Fürstenberg, geboren in Brussel, wordt ereburger van de Stad Brussel.

—Diane von Fürstenberg, born in Brussels, is made an honorary citizen of the City.

2019

—Carine Gilson fête les 30 ans de sa maison avec une rétrospective au Musée Mode & Dentelle.

—Carine Gilson viert de 30e verjaardag van haar modehuis met een retrospectieve tentoonstelling in het Mode & Kant Museum.

—Carine Gilson celebrates her house’s 30th anniversary with a retrospective at the Fashion & Lace Museum.

—Sarah Levy est la première diplômée du Master Accessoires de La Cambre à être finaliste à Hyères, dans la catégorie

« Accessoires de mode ».

—Sarah Levy is de eerste oud-studente van de master in accessoires van La Cambre die in Hyères

Il faut également comprendre que cette scène bruxelloise était très restreinte. Tout le monde se connaissait, nous nous soutenions les uns les autres. Par exemple, j’avais rencontré Xavier Delcour dans le cadre de la vie nocturne bruxelloise avant d’acheter sa collection créée avec Didier Vervaeren. J’étais une sorte de tour de guet, toujours informée de ce qui se passait.

Tout commençait et se terminait par l’habillement. Nous rêvions de mode. À l’époque, les vêtements permettaient d’accéder à un niveau supérieur. Ils étaient assimilés à de l’art. Il fallait les soutenir, les promouvoir.

C’est ainsi qu’est née la réputation du quartier. À Bruxelles, le public n’avait encore jamais vu cette association de boutiques dédiées au style de vie. Cela semblait très avant-gardiste.

Vous décrivez un milieu particulièrement riche et expérimental. Pourtant, Bruxelles ne semble jamais avoir égalé le succès international d’Anvers. Pourquoi, selon vous ?

À l’époque, les études de stylisme n’existaient pas encore à Bruxelles. Les jeunes créateurs bruxellois ne savaient pas comment se profiler sur la scène internationale. Ils avaient près de vingt ans de retard par rapport à leurs collègues anversois.

Sans parler du fait que la ville d’Anvers soutenait davantage ses stylistes. Elle s’est impliquée dans le développement du paysage culturel.

Nous, nous avons tout construit nous-mêmes, sans moyens. Nous n’avons reçu aucune aide des autorités. C’est pourquoi je

Xavier Delcour, bijvoorbeeld, kende ik al van het uitgaansleven voor ik zijn collectie met Didier Vervaeren aankocht. Ik was een beetje een uitkijktoren, ik was altijd op de hoogte van wat er gebeurde.

Alles begon en eindigde met kleding. Je droomde van kleding. Kleding was toen een brug naar iets hogers. Het werd gelijkgesteld aan kunst. Kleding was iets dat je moest ondersteunen en uitdragen.

Toen is de reputatie van de buurt ontstaan. Mensen hadden die combinatie van lifestylewinkels nog niet eerder gezien in Brussel, het voelde heel avant-garde.

Je beschrijft een ontzettend rijk en experimenteel milieu. Toch lijkt Brussel nooit hetzelfde internationale succes bereikt te hebben als Antwerpen. Hoe komt dat denk je?

Modetraining bestond toen nog niet in Brussel. Jonge ontwerpers hier wisten niet hoe ze zich moesten profileren op internationaal vlak. Brusselse ontwerpers hadden daar een achterstand van bijna twintig jaar.

Daarbij komt ook dat de stad Antwerpen haar ontwerpers veel meer steunde. De stad begeleidde mede de uitbouw van het cultuurlandschap.

Wij deden dat zelf, zonder middelen. Wij kregen geen steun van de overheid. Daarom dat ik altijd gestreden heb voor Modo Bruxellae, dat we in 1994 lanceerden. Wij waren een ontzettend klein team, met een miniem budget. Ik dacht: “Het is door samen te werken dat we kunnen groeien”. Het stylistenparcours, bijvoorbeeld, dat was heel spontaan. Iedereen die

in the Brussels nightlife scene before buying the collection he designed with Didier Vervaeren. I was always on the lookout for anything new and kept up to date on the latest happenings.

Clothing was the be-all and end-all. We would dream of fashion. At the time it was a stepping stone to something better. It was considered a form of art. It was important to support and promote these up-and-coming creative minds.

This is how the neighbourhood acquired its reputation. People had never seen such a combination of lifestyle stores in Brussels before. It felt very avant-garde.

You describe an incredibly rich and experimental scene. And yet Brussels never achieved the international status of Antwerp. Why do you think that is?

Brussels didn’t have a fashion school at that time. Young designers here didn’t know how to promote themselves in the international fashion scene. They were almost twenty years behind their Antwerp counterparts.

It must also be said that the city of Antwerp actively supported its designers, and was instrumental in creating a compelling cultural environment.

In Brussels we received no support from the local government. We were left on our own, we did it all ourselves, with very little means. That’s why I always fought so hard for Modo Bruxellae, which we launched in 1994. We were a small team with an even smaller budget. I remember thinking that teamwork would be the only way forward. The Parcours de Stylistes, for instance, came

als finaliste eindigt, in de categorie ‘modeaccessoires’.

—Sarah Levy is the first graduate of the La Cambre Accessories Master to be a finalist in the Fashion Accessories category at the Hyères Festival.

—Mansour Badjoko et Martin Liesnard créent la marque Mansour Martin.

—Mansour Badjoko en Martin Liesnard richten het merk Mansour Martin op.

—Mansour Badjoko and Martin Liesnard create the label Mansour Martin.

2020

—Olivier Theyskens est nommé directeur artistique d’Azzaro.

—Olivier Theyskens wordt benoemd tot artistiek directeur van Azzaro.

—Olivier Theyskens is named creative director for Azzaro.

—Nicolas de Felice est nommé directeur artistique de Courrèges.

—Nicolas de Felice wordt benoemd tot artistiek directeur van Courrèges.

—Nicolas de Felice is named creative director for Courrèges.

me suis toujours battue pour Modo Bruxellae, que nous avons lancé en 1994. Nous formions une petite équipe dotée d’un budget dérisoire. Je me suis dit que la collaboration nous permettrait de grandir. Le Parcours de Stylistes, par exemple, était très spontané. N’importe quelle âme créative pouvait présenter son travail au grand public.

Et nous avions indéniablement du talent. Je pense par exemple à Elvis Pompilio, Cathy Pill, Christophe Coppens ou Jean-Paul Knott. Leur créativité n’avait aucune limite. Du reste, c’est le cas de tous les Bruxellois. Ça partait dans tous les sens. Ce qui n’a naturellement pas aidé à gagner une reconnaissance internationale.

J’ai toujours entretenu des liens étroits avec les créateurs que je vendais. Sandrine Rombaux et Tony Delcampe, avec leur collection pour femmes Au Milieu Dos, Éric Beauduin ou Sofie D’Hoore, que je connais depuis l’ouverture du magasin. STIJL était un lieu de rencontre. Tout le monde y passait pour partager ou raconter quelque chose.

Ce que vous évoquez semble très intime.

C’est vrai, mais c’était aussi très élitiste. C’est la grande différence par rapport à maintenant. Aujourd’hui, la mode s’est largement démocratisée. Nous étions vraiment radicaux, nous voulions nous opposer aux normes. Quoi que nous fassions, il fallait que ce soit inédit. C’était dans l’air du temps.

En quoi cela correspond-il à votre approche personnelle de la mode ?

zich creatief voelde, kon werk presenteren aan het grote publiek.

Er was zeker talent. Kijk maar naar mensen als Elvis Pompilio, Cathy Pill, Christophe Coppens, Jean-Paul Knott. Creatief ongeremd, zoals alle Brusselaars trouwens. Dat ging alle richtingen uit. Wat het natuurlijk moeilijk maakte om internationaal succes te bereiken.

Ik heb altijd een nauw contact gehad met de ontwerpers die ik verkocht. Sandrine Rombaux en Tony Delcampe met hun vrouwencollectie Au Milieu Dos, Éric Beauduin, of Sofie D’Hoore, die ken ik al van het begin van de winkel. STIJL was een ontmoetingspunt. Iedereen kwam daar langs, even iets vertellen, delen.

Wat je vertelt, klinkt heel intiem.

Ja, maar ergens ook zeer elitair. Dat is het grote verschil met nu. Vandaag is mode veel democratischer. Wij waren echt radicaal, wij wilden ons totaal tegen de bestaande normen keren. Wat je ook deed, het moest iets zijn dat nog niet bestond. Dat was de tijdsgeest.

Op welke manier sluit dat aan bij je persoonlijke aanpak van mode?

Wat mij interesseert, zijn modeontwerpers die een eigen visie hebben. Ik heb altijd lokale ontwerpers gesteund, maar ik ben niet op zoek naar een Brusselse of Belgische look. Hoe kan die ook bestaan? Hier zijn zoveel verschillende nationaliteiten. Brussel is hybride, invloeden komen van overal. Kijk naar Olivier Theyskens. Vanaf de jaren 90 kun je eigenlijk niet

about spontaneously. It allowed each and every creative talent to present their work to the public. And there was, undeniably, no lack of talent. We had Elvis Pompilio, Cathy Pill, Christophe Coppens and Jean-Paul Knott. Their creativity had no limits, and this is the case for many Brussels-based designers. It went in many different directions, which made it difficult to achieve international recognition.

I’ve always stayed in close contact with the designers whose work I sold, be they Sandrine Rombaux and Tony Delcampe, the designers of the “Au Milieu Dos” women’s wear collection, or Éric Beauduin and Sofie D’Hoore, whom I’ve known since the shop first opened. STIJL was a place where people came to meet. There was always someone stopping by for a chat.

It all sounds very close and intimate. True, but it was also elitist. That’s the major difference between then and now. Fashion today is much more democratic. We were truly radical; we wanted to turn our backs on the status quo. Whatever you did, it had to be new. That was the spirit of the times.

How does that align with your personal approach to fashion?

What interests me are fashion designers who have a unique vision. I’ve always supported local designers, but I’m not looking to promote a specifically Brussels or Belgian style. There can be no such thing! This is a hybrid city, people come from all over. Brussels is a melting pot of multiple influences. Take Olivier Theyskens for instance. From the nineties on, one couldn’t really talk about Brussels designers. These people are cosmopolitan.

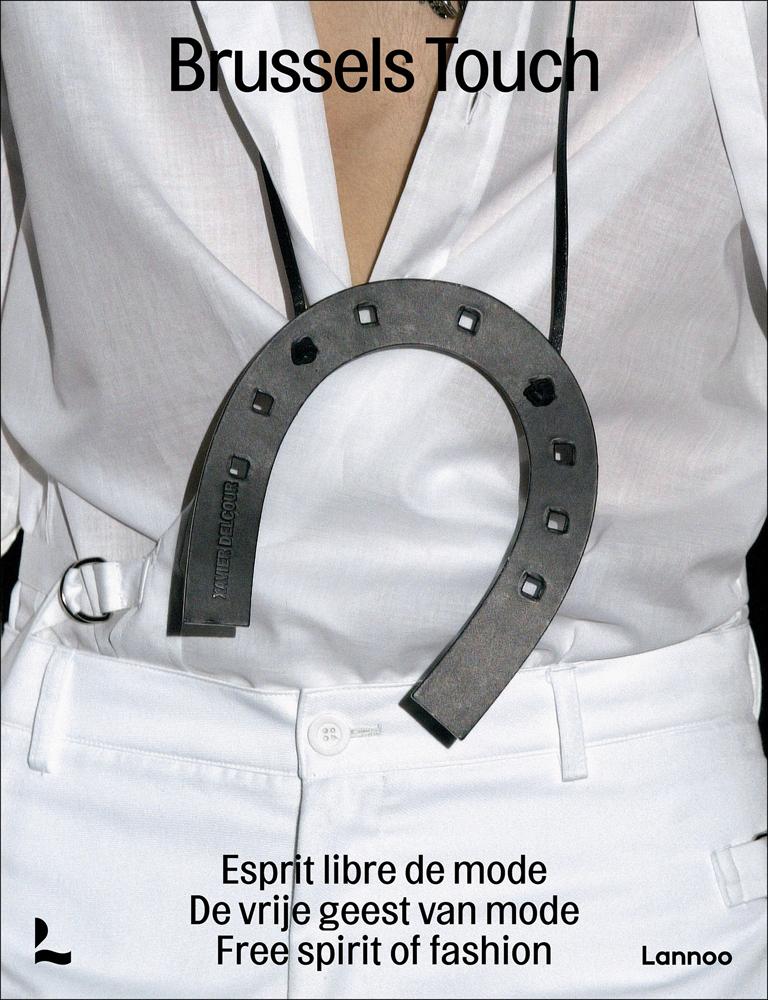

—Ouverture de l’exposition « Brussels Touch » au Musée Mode & Dentelle.

—Het Mode & Kant Museum opent de expo ‘Brussels Touch’.

—Opening of the “Brussels Touch” exhibition at the Fashion & Lace Museum.

Ce qui m’intéresse, ce sont les créateurs de mode qui possèdent une vision personnelle. J’ai toujours soutenu les stylistes locaux, mais je ne suis pas à la recherche d’un look belge ou bruxellois. D’ailleurs, comment un tel look pourrait-il exister ? Bruxelles abrite tellement de nationalités différentes. C’est une ville hybride, ses influences viennent de partout. Prenez par exemple Olivier Theyskens. À partir des années 1990, on ne peut plus vraiment parler de designers bruxellois, car ils sont cosmopolites.

STIJL s’est toujours concentré sur les silhouettes, et non sur les accessoires. Ce que j’apprécie par-dessus tout, c’est la sobriété. Le corps est très important pour moi. L’ensemble donne la première impression. Ensuite, j’observe les détails.

En fait, le style belge ne se prête pas très bien au merchandising. Pourtant, c’est sur cet aspect que l’accent porte aujourd’hui : « Investissez dans un sac à main ou un joli foulard ». Je ne suis pas d’accord. Les accessoires sont plus ostentatoires. Trop reconnaissables. Comme si on se baladait avec un logo.

J’ai remarqué une contradiction dans vos propos. Le client STIJL veut se démarquer, mais de manière subtile ?

Son style est discret, sans logo, mais parfaitement reconnaissable des initiés. C’est ce qui, à l’époque, constituait l’attrait de la rue Dansaert.

Toutes les rencontres que j’ai faites grâce à STIJL sont magnifiques. Parfois, j’ai l’impression que c’était ma mission. Ma vocation.

Cela paraît évident.

meer spreken over Brusselaars. Dat waren kosmopolieten.

STIJL heeft altijd op silhouetten gefocust, in plaats van op accessoires. In de eerste plaats hou ik van soberheid. Het lichaam is zeer belangrijk voor mij. De eerste indruk is het geheel, dan pas ga je in de details.

De Belgische stijl leent zich eigenlijk niet zo goed voor merchandising. Daar wordt vandaag nochtans de nadruk op gelegd: “Investeer in een handtas of een mooie sjaal.” Ik ben het daar niet mee eens. Accessoires zijn ostentatiever. Te herkenbaar. Alsof je met een stempel rondloopt.

Ik zie een tegenstelling in wat je vertelt. De STIJL-klant wil uitblinken, maar op een subtiele manier?

Het is understated, maar herkenbaar voor insiders, zonder logo. Dat is wat Dansaert toen aantrekkelijk maakte.

Het is ontzettend mooi, alle ontmoetingen die ik via STIJL meemaakte. Soms voelt het alsof ik dit moest doen. Alsof dit mijn roeping was.

Zo klinkt het ook.

STIJL has always focused primarily on the silhouette, more than accessories. I appreciate restraint, austerity. The body is very important to me. The whole is what forms a first impression, then I take a closer look at the details.

In all honesty, Belgian style doesn’t lend itself well to merchandising. But these days, it’s all about “investing in a good handbag or a pretty scarf”. I don’t agree with this. I think accessories are too ostentatious, too recognisable. It’s like walking around with a badge.

It seems to me that this contradicts your stance. STIJL customers seek to stand out, but in a more subtle way?

Their style is understated, with no logo in sight, yet it is instantly recognisable to insiders. That’s what made rue Dansaert so attractive in the first place.

All the people I’ve met through STIJL are wonderful. Sometimes it feels like I was meant to do this. Like it was my calling.

That’s certainly what it sounds like.

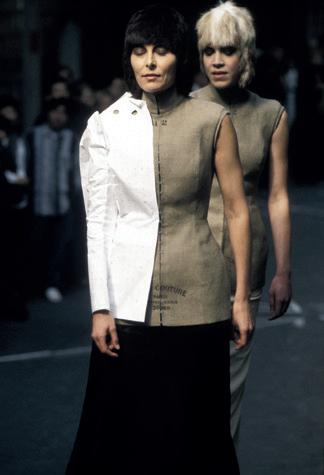

sans manche, toile de lin | Mouwloos jasje, linnenbinding | Sleeveless jacket, linen toile Martin Margiela, S/S 1997 — REF. MUS. C2019.128.01

sans manche, toile de lin | Mouwloos jasje, linnenbinding | Sleeveless jacket, linen toile

Martin Margiela, S/S 1997 — REF. MUS. C2019.128.01