Wildlife Road Crossings (WRC’s)

The importance of wildlife migration has gained widespread attention as rapid climate change forces entire natural communities to shift and adapt. Yet, a dense network of roads now criss-crosses nearly every landscape, severing migration routes and cutting off many mammals and other species from the critical habitats they need to survive.

Well-funded studies have justified significant investments in migrational bridges to reduce the heavy toll of wildlife-vehicle collisions. While these efforts often focus on large mammals, it’s essential to recognize that plant communities also migrate and they rely on insect pollinators to move with them To truly conserve biodiversity, we must consider the interconnected migration patterns of not just mammals, but also plants and insects.

Wildlife migration bridges are critical for restoring connectivity across major roadways and the landscapes that they fragment. However, to maximize their effectiveness and cost-efficiency, they must be integrated into broader conservation networks that include numerous lower-cost Wildlife Road Crossings (WRCs). WRC’s play an essential role in maintaining broader ecological connectivity and building long-term resilience of natural communities

The migrational bridge above looks fantastic, but the miles of highway on either side constitute a major trap for seeds, plants, and insects Yes, many mammals will find the bridge, but this is just a small fraction of the species moving due to climate change.

The challenge lies in the inadequacy of sporadic mammal migration bridges on vast landscapes in sustaining overall biodiversity. Presently, entire forested communities are undergoing migration. Consequently, a mere 100-foot-wide wildlife migration bridge every five miles falls

short when considering the evolutionary dynamics of plants and insects. Such bridges offer less than 1% of the landscape connectivity that once existed, jeopardizing the survival of numerous species

Mammals migrate to find ever-shifting food sources, which for herbivores and their predators means that significant distances are often traveled. Plants also migrate for various reasons, including rising temperatures, forest succession, and in relation to insect pollinators. Insects create the biological foundation for all terrestrial ecosystems. They cycle nutrients, pollinate plants, disperse seeds, maintain soil structure and fertility, control populations of other organisms, and provide a major food source for other taxa (Wiley Online) Butterflies (for example) are sensitive to environmental factors, and slight changes can cause rapid population declines. Climate change is likely to affect moisture and temperature regimes, and thereby disrupt migratory cues. Anderson & Brower(1993)

According to a meta-analysis of 16 studies, insect populations have declined by about 45% in just the last 40 years. The large-scale death of insects poses huge threats not only to the ecosystems they exist in but also to much of our agriculture. (UC Riverside Dept of Entomology.)

Insects are vulnerable to climate change and many need to migrate to survive.

https://largelandscapes.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/Wildlife-vehicle-Conflict-Crossing-Stru ctures-and-Cost-Estimates.pdf

While exceedingly costly wildlife bridges and tunnels targeting specific species do mitigate collision expenses However, it's imperative to devise viable solutions for small towns and states in the US and around the world, which struggle to afford even basic infrastructure maintenance The solutions recommended by organizations such as The Center for Large Landscape Conservation are not financially realistic in most areas.

The vast majority of studies on wildlife road crossings center on interstate highways with speed limits of 55 - 65 miles per hour. The results show that small reductions in speed do not reduce Wildlife Vehicle Collisions (WVCs). However, a study by Georgia Southern University found that dirt roads have a very low WVC rate as do roads with speed limits of 35 mph

https://digitalcommons georgiasouthern edu/cgi/viewcontent cgi?article=1316&context=honors-t heses

Having less than 5% of a rural community's roads with a 35 mph speed limit is a small price to pay for maintaining an area ' s biodiversity.

Solutions with significantly lower price tags are urgently needed for the majority of low to medium-traffic roadways in rural areas. The Vermont Department of Fish and Wildlife underscores the importance of large blocks of contiguous forest and secure connections between them for various wildlife species.

“Many wildlife species rely on large blocks of contiguous forest and secure connections to other large forest blocks for all or part of their habitat needs For instance, the home range of an adult male black bear can be as large as 50 square miles. Black bear, fisher, otter, bobcats, and other species of wildlife move great distances to find food, water, dens, refuge, and other important habitat resources. Many songbirds require large areas of forest cover that are free from fragmentation and human disturbance. There are many other recognized ecological, social, and economic values of large contiguous forest blocks. These areas represent many of the natural heritage values and support the rural working landscape that makes Vermont unique in the developing landscape of the northeast” (The Vermont Department of Fish and Wildlife)

https://fprvermont gov/sites/fpr/files/Forest and Forestry/Vermont Forests/Library/VFWD%20 Habitat%20Block%20Report-April%202014.pdf

Most areas are heavily fragmented by roads, necessitating the conservation of wildlife migration road crossings to maintain a landscape's ecological, social, and economic values. The initial step involves studying where wildlife currently crosses roadways, as exemplified by the Wildlife Road Crossing Study conducted in Marlboro, Vermont. Ideally, these studies focus on successful

crossings not just locations where wildlife-vehicle collisions occur to better understand existing connectivity ( In areas where mammal populations have declined, such as the Ecuadorian Amazon, interviews with elders and hunters reveal that migration patterns tend to follow universal patterns. Landscapes naturally funnel most wildlife in predictable ways. The next article in this series will explore how to design future wildlife migration networks in areas where localized extinctions have already taken place.)

Studies by the Marlboro Vermont Conservation Commission (Study description to follow) found that over 20 wildlife road crossings were actively used by local mammals in the 30,000-acre town The town acts as a functional biocorridor and the network of many wildlife road crossings is required for the town to maintain diverse natural communities

Vermont has 237 towns If 100 towns need 20 migration structures each to maintain wildlife migration, the total price tag would be $500 million and that's only using the bottom of the price range for these types of structures.

More affordable solutions have been proven to work for the majority of low to medium-traffic roadways with low speed limits. They are urgently needed now.

The Town of Marlboro Vermont, Wildlife Road Crossing Study. (WRC)

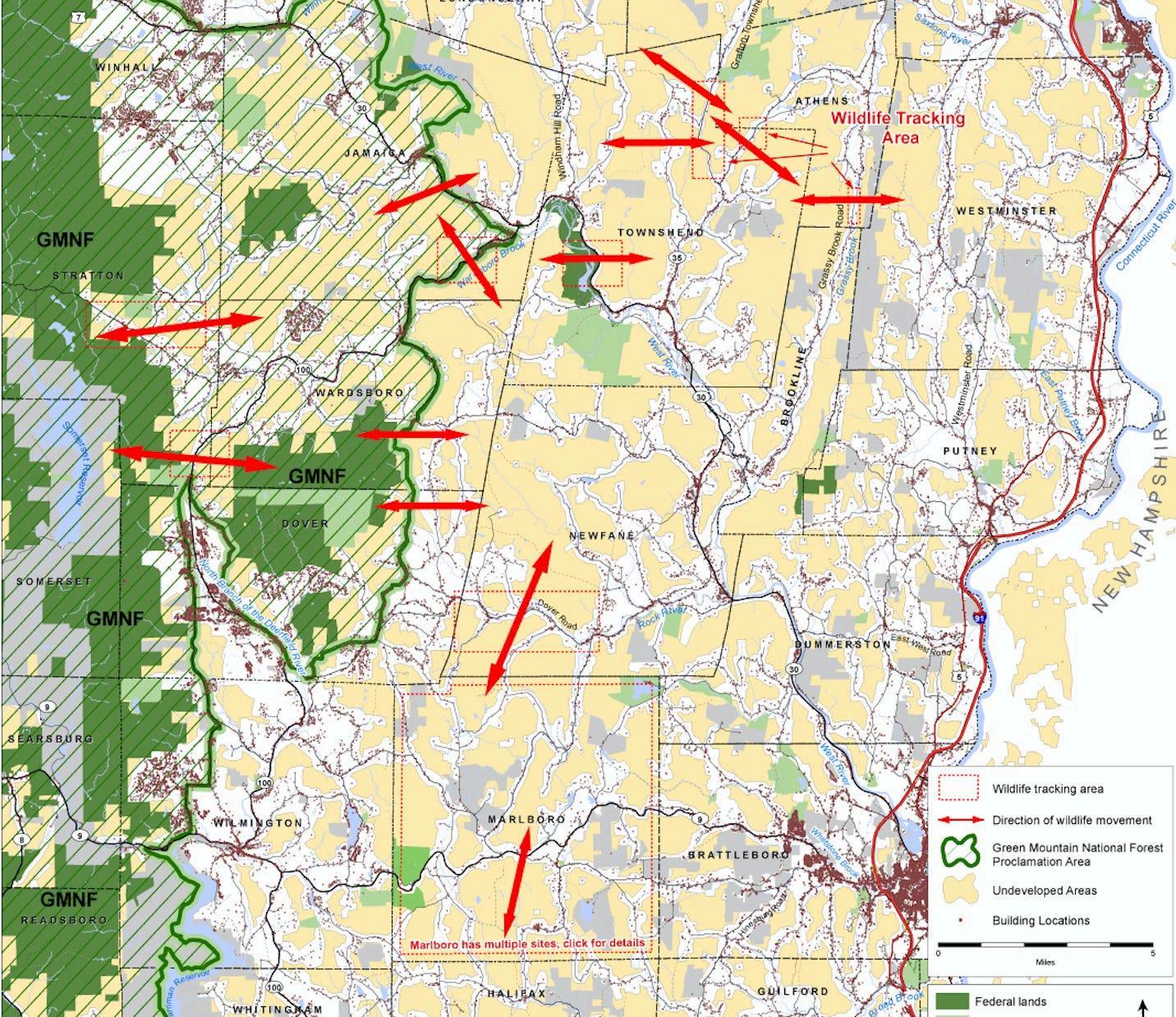

The 20 green cross-hatch areas in the map below are proven WRC’s in the 30,000-acre town.

Data collection in Marlboro involved conducting surveys over a 10-year period, during which monitors documented animal tracks in the snow along roadsides. Wildlife Road Crossing hotspots were identified with data shown on maps like the one below The numerous yellow

dots are houses along local roads. The colorful symbols represent species that crossed roads as shown in the legend under the map Of note are the 3 migrational hot spots

Wildlife Road Crossing hot spots are where the three conglomerations of colorful symbols are

The study started in Marlboro, Vermont, and was then expanded by the Green Mountain Conservancy to include many neighboring towns in an area of 800,000 acres between the Connecticut River Valley and the Green Mountain National Forest.

In the process, a functional biocorridor was documented in a region with a mix of human development, farms, and forestlands.

In the map below, each red arrow represents an important wildlife road crossing in Windham County, Vermont. Beige areas are forested. White areas are developed. Dark green areas are conserved and include the Green Mountain National Forest (GMNF)

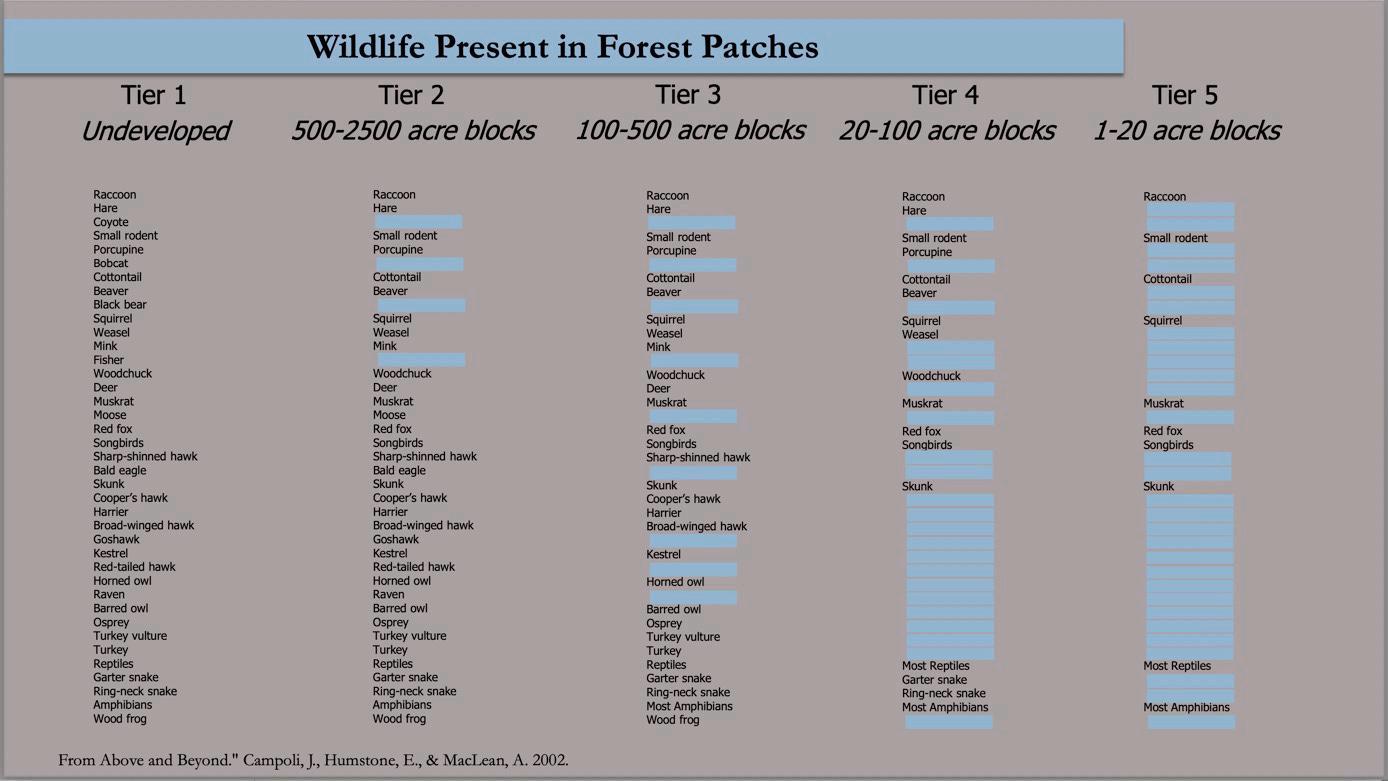

On the right side of the map above, the forested patches (in beige) are smaller and gray/white developed areas are larger The Connecticut River Valley has more landscape fragmentation and therefore less wildlife road crossings Localized extinction is well underway Steep drops in biodiversity occurred in alignment with the diagram below.

Above and Beyond." Campoli, J., Humstone, E., & MacLean, A. 2002

Localized extinction is accelerating around the world

Unless networks of Wildlife Road Crossings are conserved, local biodiversity will drop significantly Vermont has thousands of WRC’s that are fully functional but not yet documented As they are lost to development, an area ' s diversity and rural character are declining.

In Vermont, Bobcats are the first to go, and as development gets too thick, what remains tend to be raccoons, cottontails and rodents.

WRC networks should strive to connect as many ecological communities as possible in an area.

Each WRC will host a different mix of species that will change over time. After WRC networks have been identified, both sides of the roads in many locations need to be conserved. For the cost of one wildlife migration bridge ($6,000,000 at the low end of the spectrum), a network of WRC’s could be conserved through a mix of purchases and easements

Below is a general example of an ideal WRC

WRC’s need to have the following qualities to succeed;

1- Native forest maintained right up to both sides of the road helps to facilitate migration of mammals, plants and insects Mature trees typically have canopies that connect across roads offering canopy connectivity.

2- WRC networks that maintain connectivity between an areas diverse ecological communities will be capable of maintaining higher biodiversity

3- Straightaways increase visibility and reduce collisions

4- Implementing lower speed limits will also reduce collisions. Speed bumps may be necessary.

5- To minimize edge effects, the width of the undeveloped migration area should be a minimum of 500 meters along the road whenever possible. WRC’s as narrow as 50 meters have been documented as functional but are more vulnerable.

6- Signs help to raise awareness

7- Volunteers for amphibian and reptile crossings are needed during key migration times

Historically, the best wildlife migration routes have been stream and river valleys WRCs, where a stream passes under a road, offer some of the best long-term opportunities to maintain biodiversity On the other end of the spectrum, highway overpasses are a great way to bring awareness to the conservation of functional bio corridors/conservation networks that some fortunate communities are a part of.

A diverse Wildlife Road Crossing (WRC) network, spanning a range of geographic and climatic conditions, will support not only mammals but also plants, insects, and the ecological relationships between them. This diversity fosters more resilient ecological communities. Over time, continued innovation building on past successes like rope bridges for howler monkeys,

turtle tunnels, and bear overpasses will lead to even more effective strategies for reducing wildlife-vehicle collisions

The return on investment for large migrational bridges is significantly amplified when they are integrated into well-researched conservation networks that include a multitude of Wildlife Road Crossings (WRCs). Most WRCs are located on low-traffic roads, which comprise 80% of the U.S. transportation grid. Conserving these crossings now ensures future-ready infrastructure options that can be enhanced as resources allow. In Vermont alone, protecting at least 2,000 WRCs is essential to sustain viable wildlife migrations. Globally, rural communities are at a crossroads: either conserve biodiversity or face the irreversible consequences of localized extinction Human-driven habitat fragmentation is isolating wildlife populations, leading to genetic decline and threatening their future survival.

Functional biocorridors already exist in many communities hidden in plain sight, waiting to be identified and protected. Windham County, Vermont offers a compelling example: its mix of towns, farms, and forests forms a living biocorridor that remains viable, provided there are enough Wildlife Road Crossings (WRCs) to maintain connectivity. Swift action is critical to safeguard these WRC networks before poorly planned development renders conservation economically impractical Growing human populations can coexist with thriving natural ecosystems Conservation networks that maintain landscape connectivity not only protect biodiversity, but also safeguard clean water resources and other essential ecosystem services required for a sustainable future.

Note: There are now countless studies documenting roadkill around the world a grim reminder that dead animals are easy to find. What’s far more challenging, and far more valuable, is identifying where animals are successfully crossing roads. This requires time, resources, and a commitment to tracking and observation but it’s essential for designing effective wildlife migration corridors and reducing future losses