Life, Space, Buildings

How can phytoremediation processes at White Bay provide a framework for a mixed tenure neighbourhood?

Process Log

Hamzah Mulla

How can phytoremediation processes at White Bay provide a framework for a mixed tenure neighbourhood?

Process Log

Hamzah Mulla

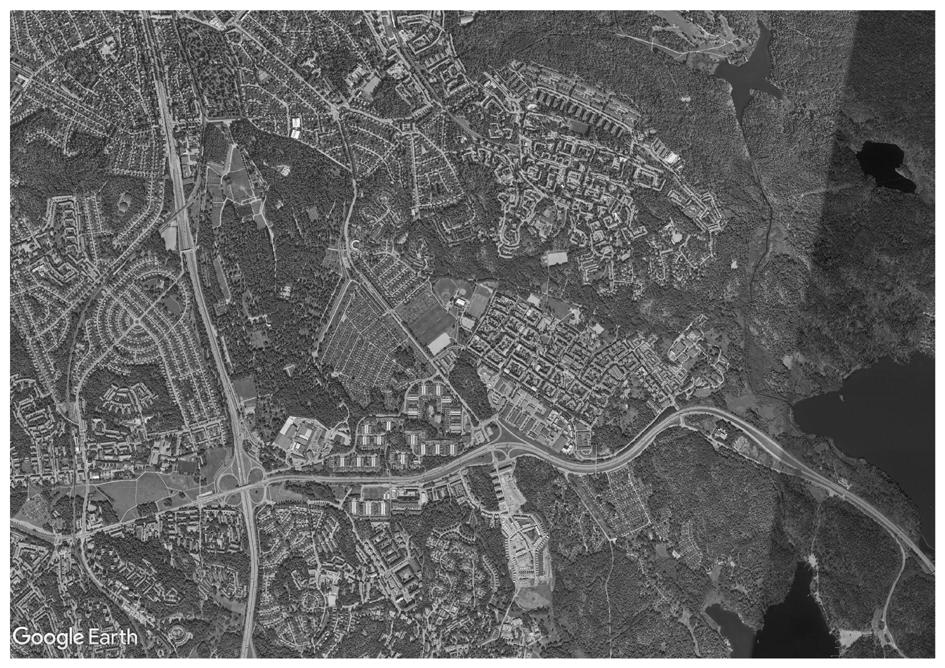

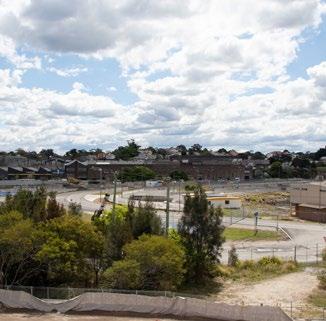

The first look at the Bays involved coming up with a structure plan for the entire precinct. This first step was largely focused on environmental sustainability

The first step at looking at sustainability within the Bays was through the context of environmental sustainability. As part of a group, a structure plan was created that envisioned a circular economy within the Bays. Here Sydney’s waste would be collected and recycled or remade into products which would drive the economy on site. The structure plan also placed an emphasis on car-less neighbourhood design.

1. Create a regional recycling hub for Inner West

2. Establish a circular economy within site

4. Create a natural waterfront stormwater filter 3. Combine industrial recycling use with an urban mixed-use neighbourhood

1. Prioritise slow movement of pedestrians and create convenient cycling routes 2. Develop a network of rooms across the Bays precinct to slow pedestrian traffic 3. Create car free neighborhoods

Alongside developing a structure plan for the Bays, I was required to explore a research topic. For this I chose to explore the idea of social sustainability and social equity in design. My research specifically focused on how design processes can be socially equitable. This would form the beginning of my focus on social equity for the following work throughout the year.

Timeline of community involvement

Location: Berlin, Germany

Completed: 2014

Size: 40 ha

Park am Gleisdreieck was built on the site of a former railway line which was abandoned after WWII. The site has had a strong history with citizen initiatives, with citizens banding together to block development proposals in the 70s and early 90s. In 1999 several citizen initiatives banded together to form the group AG Gleisdreieck, with the goal of lobbying for the construction of a park. The Berlin government eventually launched a park design competition which was won by Atelier Loidl. The following year a thorough participatory planning procedure began which included: a citizen survey, an online forum and on site activities. The next stage of the planning process began in 2007 and continued to involve local citizens, who were encouraged to present different design visions for the park to the design team. In 2011 the eastern section of the park was completed and in 2014 the western section was completed (Müller 2020).

• A balance was struck by the designers between a top down and bottom up design approach

• Citizens were able to have their say during the design phase through a variety of means such as: a citizen survey, an online forum, on site activities and design charettes

• After the completion of the park an online citizen advisory board was set up to provide feedback and discuss new developments and events

• The range of programming reflects the social diversity of the park’s users

• The programming of the park was heavily informed by the different stages of community consultation

• The participatory design approach meant local citizens were able to ensure a number of programs were added to the plan of the park

Formal sports

Informal sports

Community gardens

Formal spor ts

• The designers created formal and informal “stages” in order to create a feeling of togetherness throughout the park (Grosch and Petrow 2016)

• The “stages” bring together people from all backgrounds and create an environment in which they can take note of each other, this results in interaction and communication

• Informal “stages” provide an informal space in which visitors can observe a range of activities

• Formal “stages” are more formal spaces which are dynamic enough to play host to a number of activities.

Informal “stages”

Allotment gardens

Informal spor ts

Community gardes

Dog park

Allotment gardens

Formal “stages”

Seniors fitness

Dog park

Playground

Playground

Table tennis

Bocce Seniors fitness

Table tennis

Bocce

The focus for the second term moved towards putting parts of my research into practice and adapting the design of one of the neighbourhoods from my structure plan. The goal was to design a neighbourhood with a focus on fostering a socially sustainable community

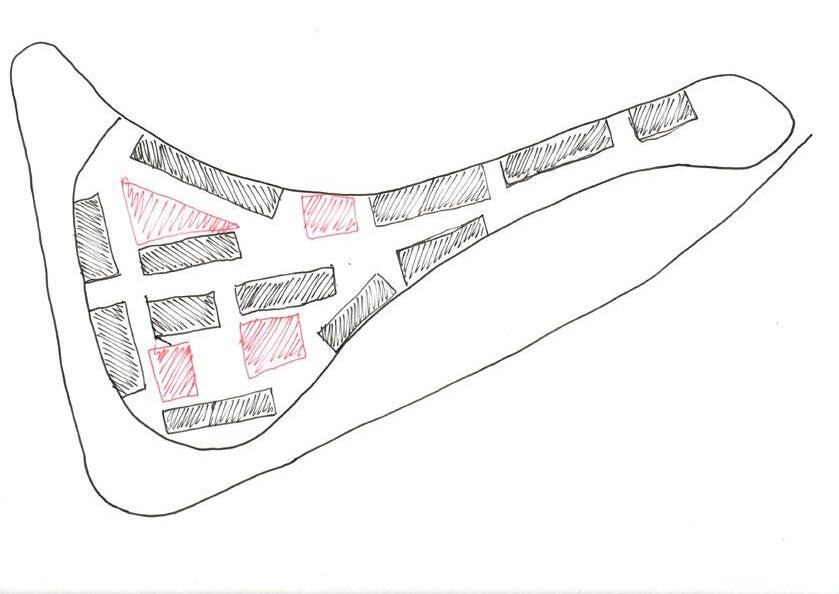

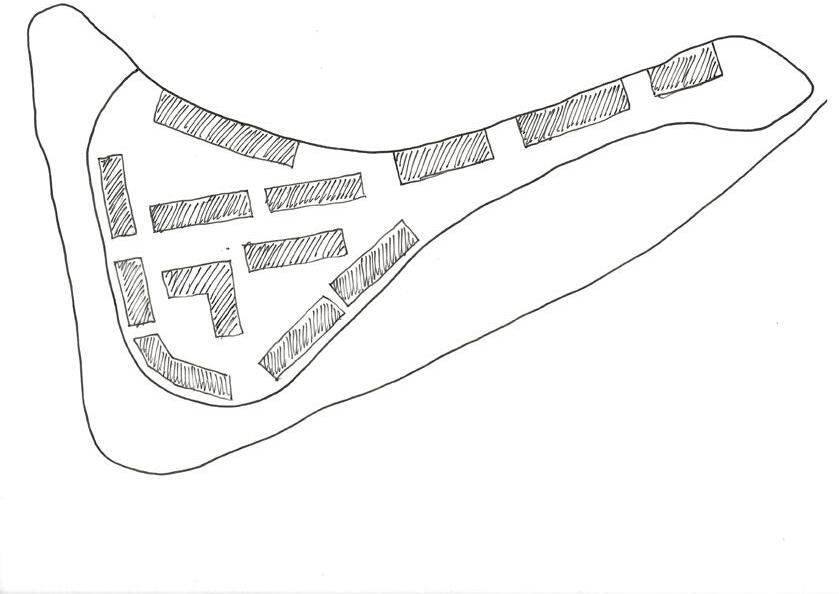

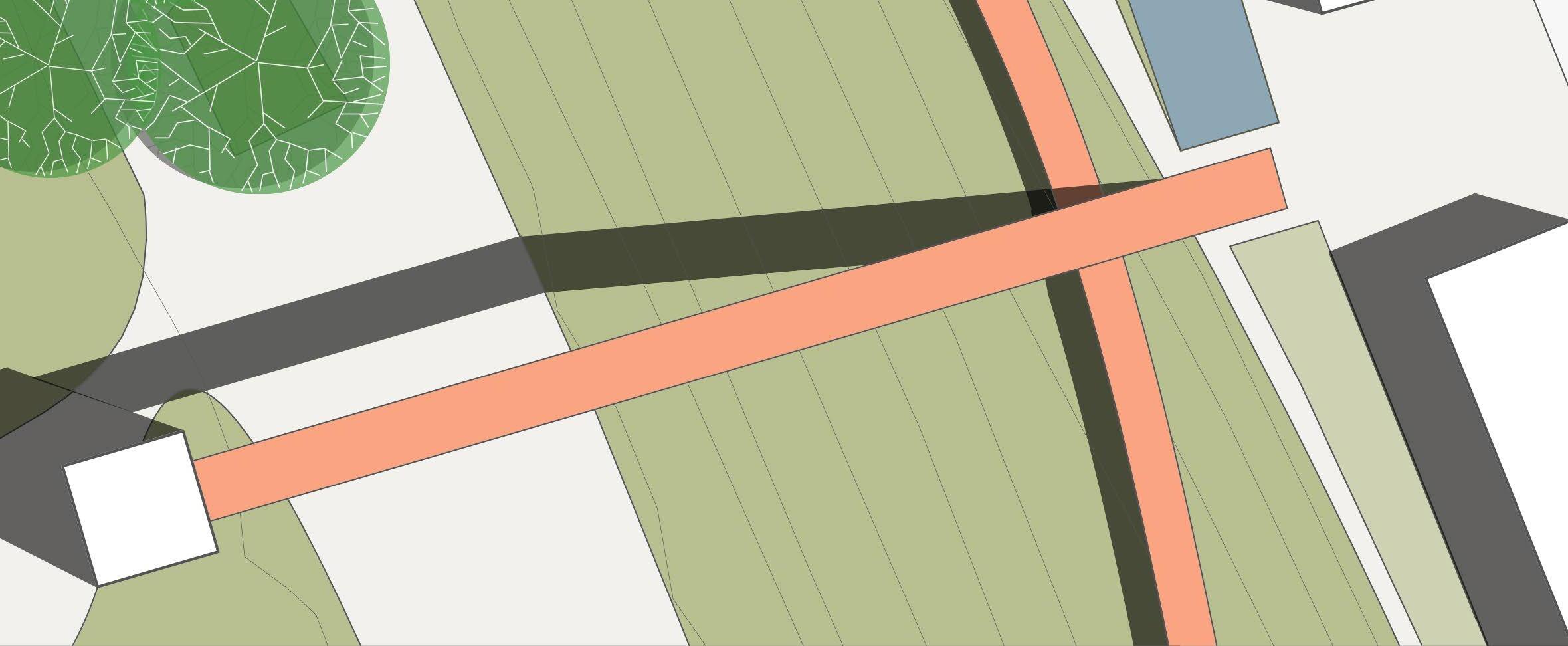

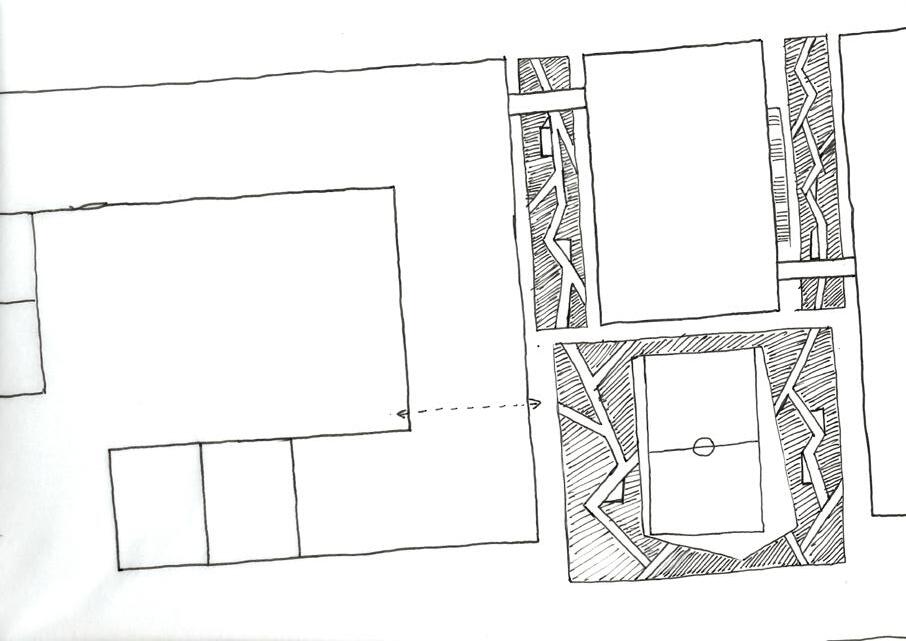

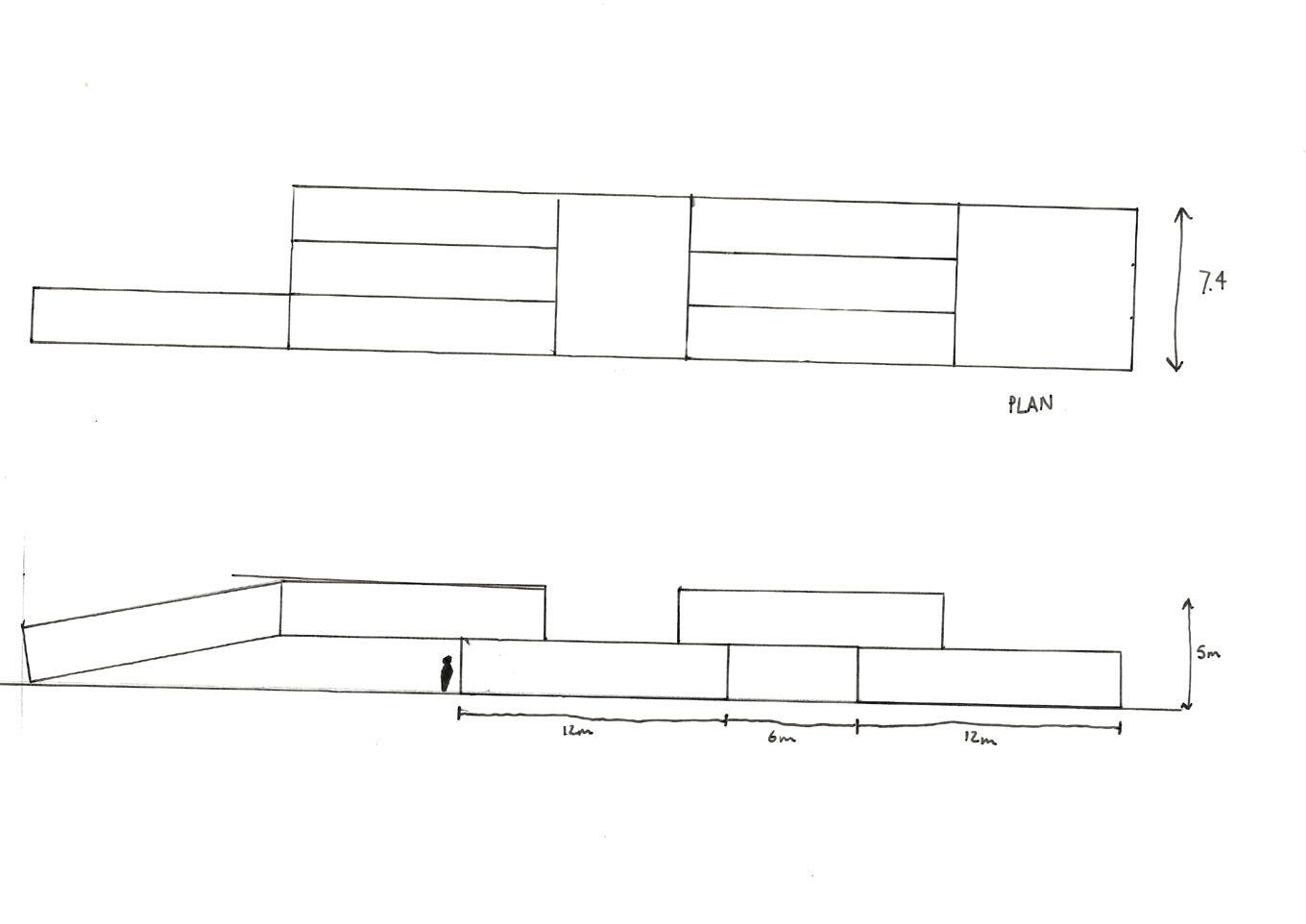

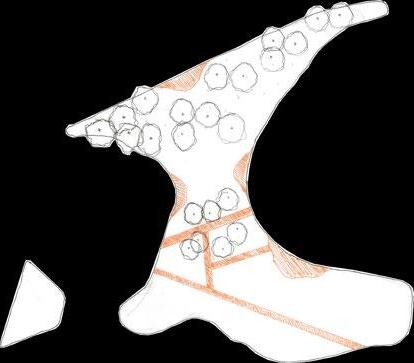

The first look at what a mixed tenure neighbourhood was on the current site of the passenger terminal.

Globally a trend has started to emerge, where cities seek to revitalise neighbourhoods through the creation of mixed-income neighbourhoods1. This has brought issues around gentrification and social equity to the fore. Despite the idea that gentrification is largely driven by economic factors, research has shown that landscape can cause environmental gentrification. Both small and large scale interventions can result in environmental gentrification.2 In the context of this problem my topic seeks to explore how landscape architects can create socially equitable spaces as part of urban renewal projects.

Despite a high proportion of high income earners in the neighbouring suburb of Balmain, there still exists a minority population of low income residents3. This minority population could increase in the future as the Inner West Council is currently pushing to have at least 50% of all new dwellings in the Bays West redevelopment scheme to be listed as affordable housing4. This potential creation of a mixed income neighbourhood would be a reversal of the gentrification process but would still raise questions as to how a socially sustainable community could be built.

Study area

Scale: 1:5000

1 Madanipour, A 2011, ‘Living together or apart’, in Banerjee, T & Loukaitou-Sideris, A, Companion to Urban Design, Routledge, London, pp. 484-494W

2 Rigolon, A & Németh, J 2018, ‘“We’re not in the business of housing:” Environmental gentrification and the nonprofitization of green infrastructure projects’, Cities, vol. 81, pp. 71–80.

3 Australian Bureau of Statistics 2026, Australian Bureau of Statistics, Canberra, accessed 11 April 2007, <https://quickstats.censusdata.abs.gov.au/census_services/getproduct/census/2016/quickstat/SSC10164>

4 Inner West Council 2021, accessed 10 June 2021, < https://www.innerwest.nsw.gov.au/develop/state-government-and-utility-works-and-projects/state-government-projects/bays-precinct>

Principle 1: Create an inclusive neighbourhood

Cities that are inclusive of everyone tend to be more socially equitable than cities that fail to include everyone. In order to create an inclusive city or neighbourhood, public spaces need to provide a use for everyone from children to the elderly.1

Objective 1.1: Eliminate semi private/privatisation of public space

Truly inclusive neighbourhoods should provide equitable access to public space and prevent segregation.

Objective 1.2: Provide a range of programs that reflects the range of potential users of the site

Inclusive neighbourhoods need to provide a use or activity for a wide range people.

Objective 1.3: Use visual cues and clear sight lines to highlight public spaces

Site entrances that clearly indicate that spaces within are publicly accessible encourage people to explore within.

Principle 2: Build a socially sustainable community through the creation of CRE’s (Communication Rich Environments)

In order to build a socially sustainable community, citizens need to build stronger connections with each other and thus accumulate social capital. Social capital is defined as networks of people who engage with each other in a symbiotic relationship. Communication rich environments (CRE) facilitate the building of social capital within neighbourhoods by facilitating diverse forms of interaction between a wide range of people2.

Objective 2.1: Create a series of community gardens for local residents and businesses

Community gardens provide a sense of shared purpose among a community which allows them to build connections.

Objective 2.2: Create temporary use spaces that can be managed by locals (galleries, exhibitions, markets)

Spaces that are flexible, informal and encourage temporary use create a relaxed atmosphere that allows interaction to occur.

Objective 2.3: Create spaces for play

Encouraging people to play helps engage them with their neighbourhood and has the potential to attracts a wide range of people.

1 Chase, K & Rivenburgh, N 2019, Envisioning Better Cities, A global tour of good ideas, ORO Editions

2 Chase, K & Rivenburgh, N 2019, Envisioning Better Cities, A global tour of good ideas, ORO Editions

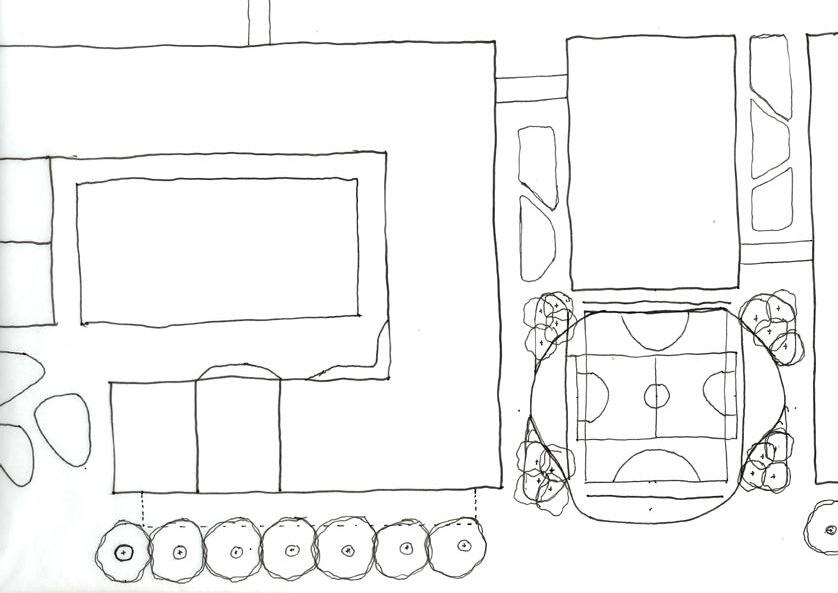

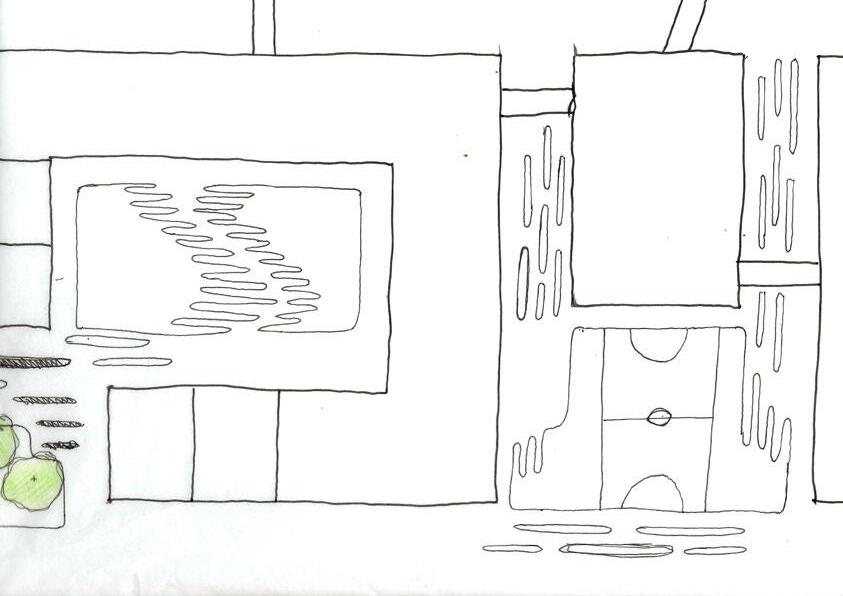

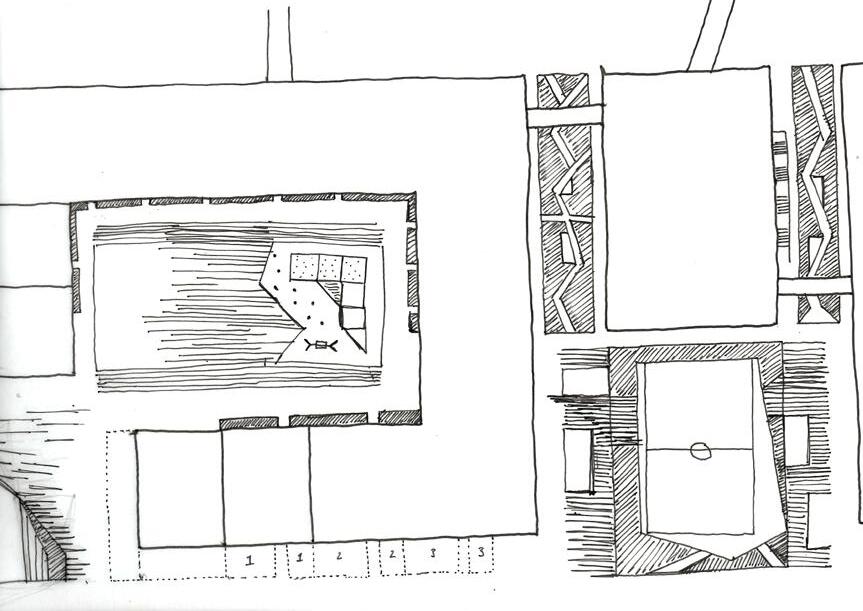

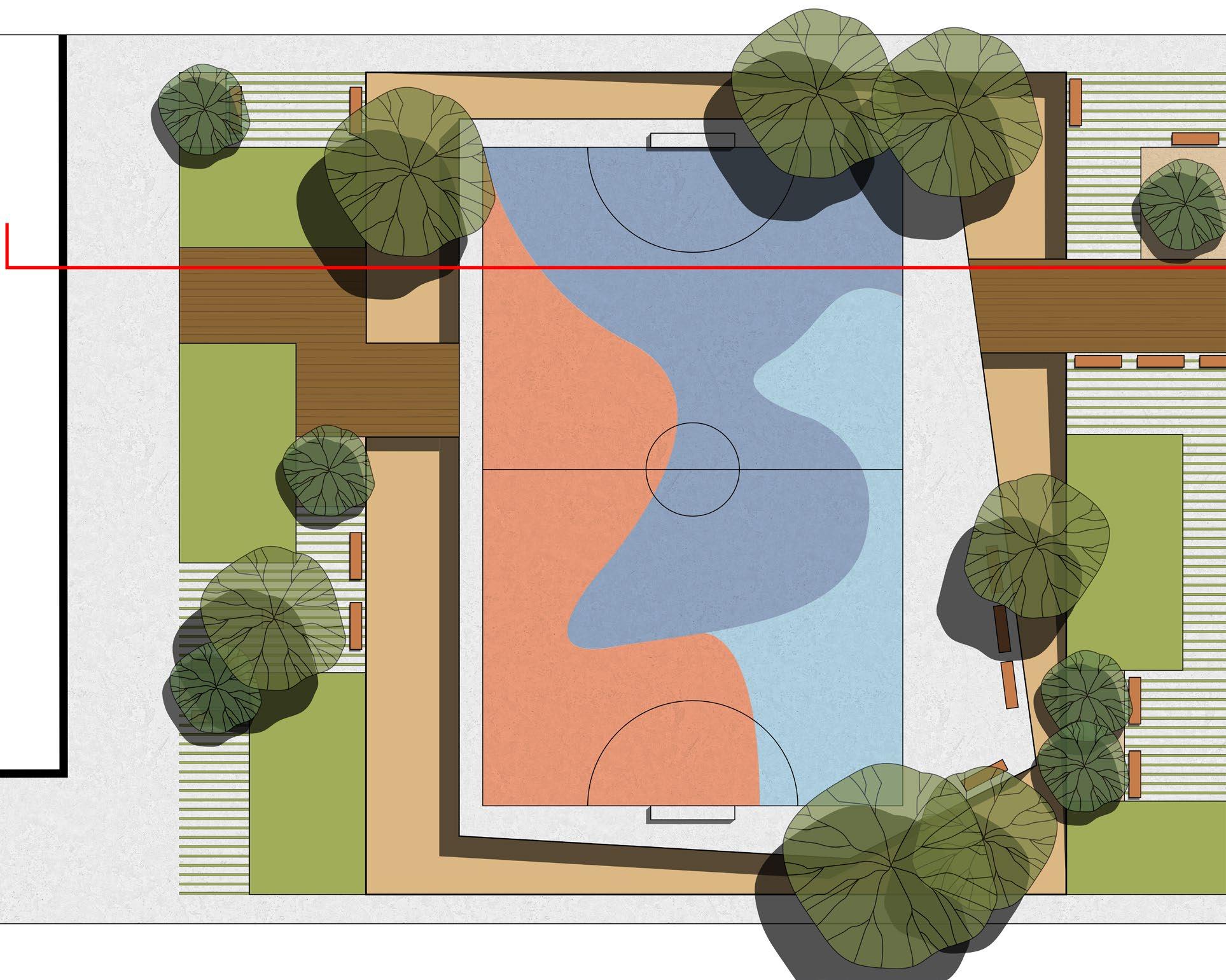

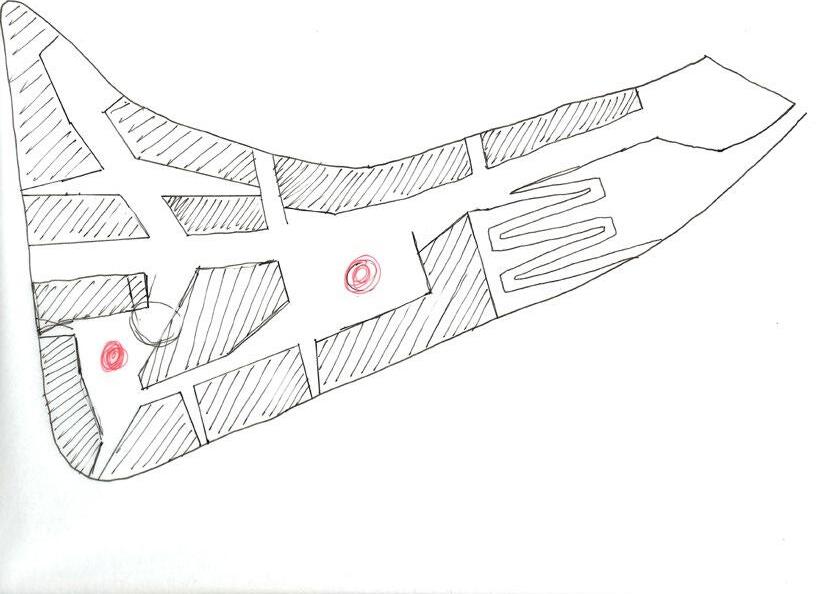

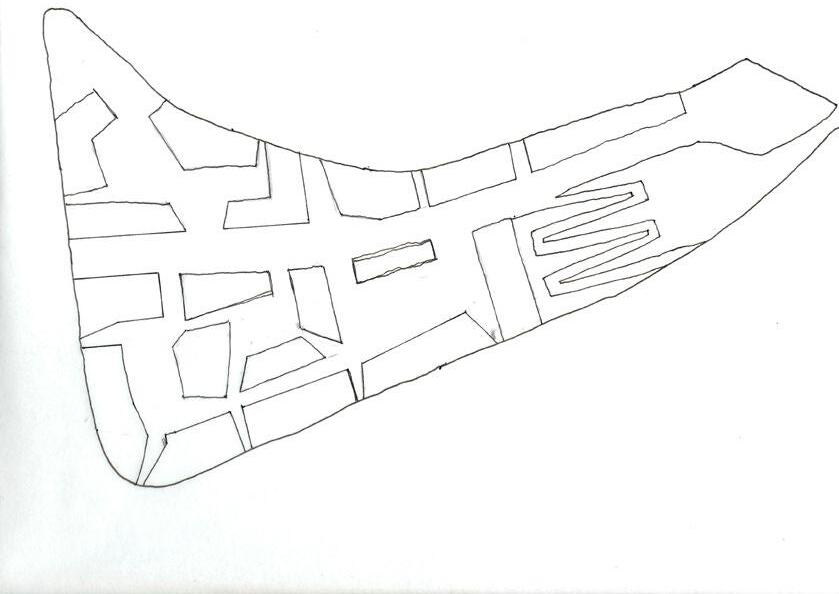

1. Neighbourhood as designed in the structure plan

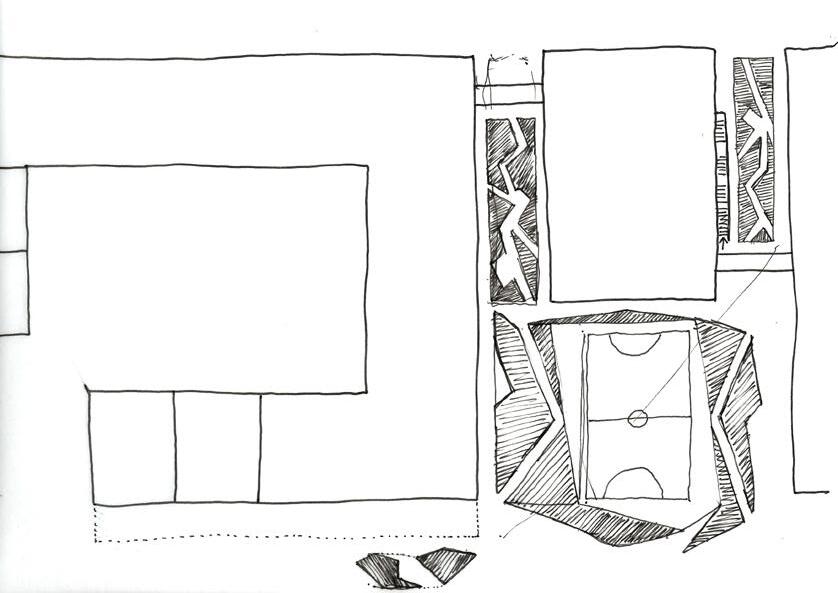

3. The idea of a playground felt better suited for elsewhere, instead the idea of a sports court was explored

2. Explored the idea of creating a playground in the plaza

4. Began to introduce the idea of a paving style as a way of moving users through the site

5. Introduced the idea of parklets as a way of introducing visitors to the site

7. Reintroducing the idea of a paving as a visual indicator

6. Exploring forms and circulation

8. Final public domain design

Restaurants utilise the publicly accessible community gardens - with a few plots available to residents

Terrace seating

A paving pattern is used throughout the site as a visual indicator of public space

Paving style is similar to other parts of the site

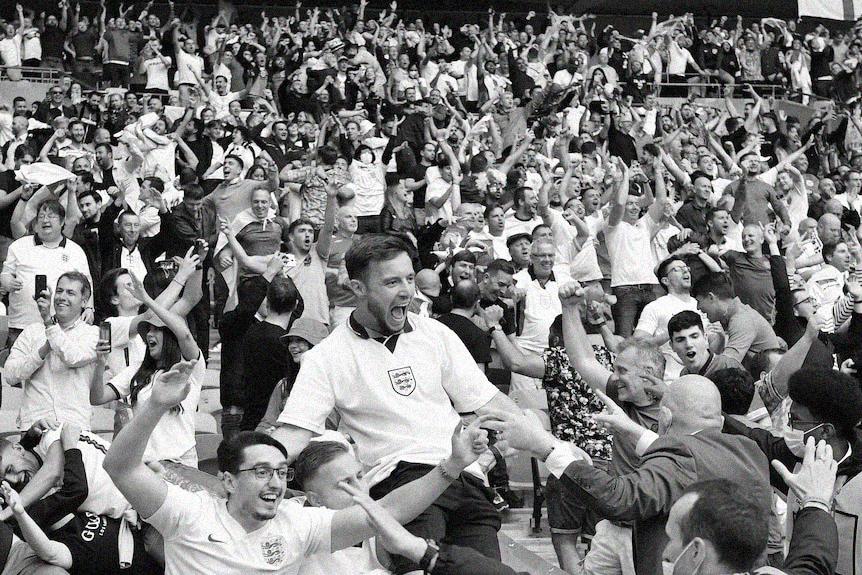

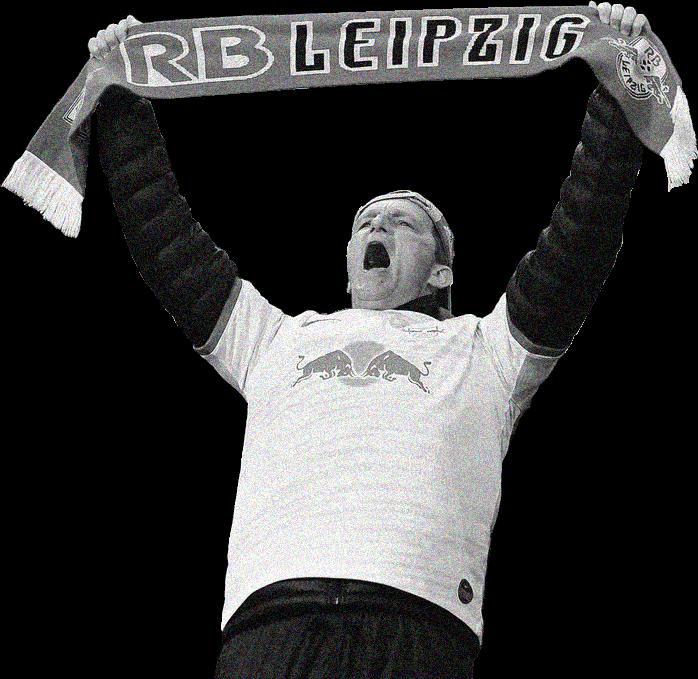

Part of this term involved creating abstract artworks by combining some research questions with two additional topics. For this looked at combining football, modernism and socially equitable design

Match day atmosphere Constructivism

Let’s Fulfill the Plan of Great Works - Gustav Klutsis - 1930

Can Landscape Architecture take inspiration from the methods used to create match day atmospheres?

Bleacher Report 2015, accessed 12 July, < https://bleacherreport.com/articles/2473989-borussia-dortmund-thank-outgoing-jurgen-klopp-with-incredible-display> MOMA 2021, accessed 2 July 2021, < https://www.moma.org/collection/works/6487?artist_id=12501&page=1&sov_referrer=artist>

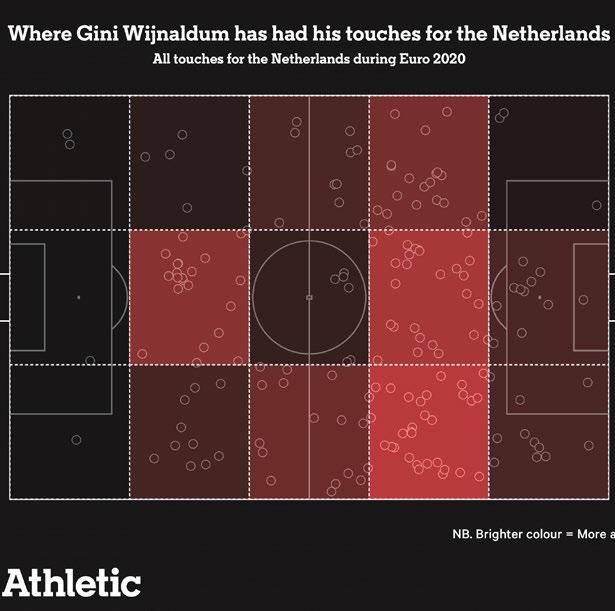

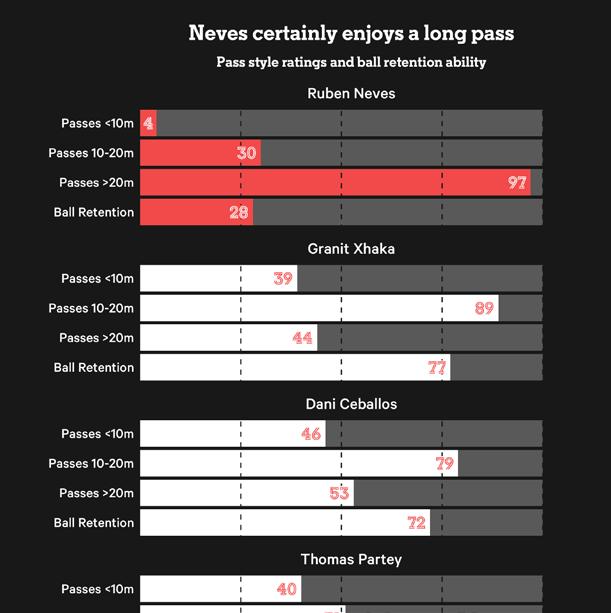

heat map and touch analysis

Can we better analyse sites in a way that results in a more equitable outcome?

comparison chart

Archeyes 2021, accessed 12 July 2021, < https://archeyes.com/architects/mies-van-der-rohe-biography-bibliography/> Instagram, accessed 12 July 2021, < https://www.instagram.com/p/CN7QO0IhLA4/?utm_medium=copy_link> The Athletic 2021, accessed 1 July 2021, < https://theathletic.com/2638630/2021/06/09/is-neves-a-xhaka-replacement-for-arsenal/>

Can we better analyse sites in a way that results in a more equitable outcome?

The following principle championed by Jan Gehl became a key tenet of the following design and analytical work

“The widespread practice of planning from above and outside must be replaced with new planning procedures from below and inside, following the principle: first life, then space, then buildings.” - Jan Gehl

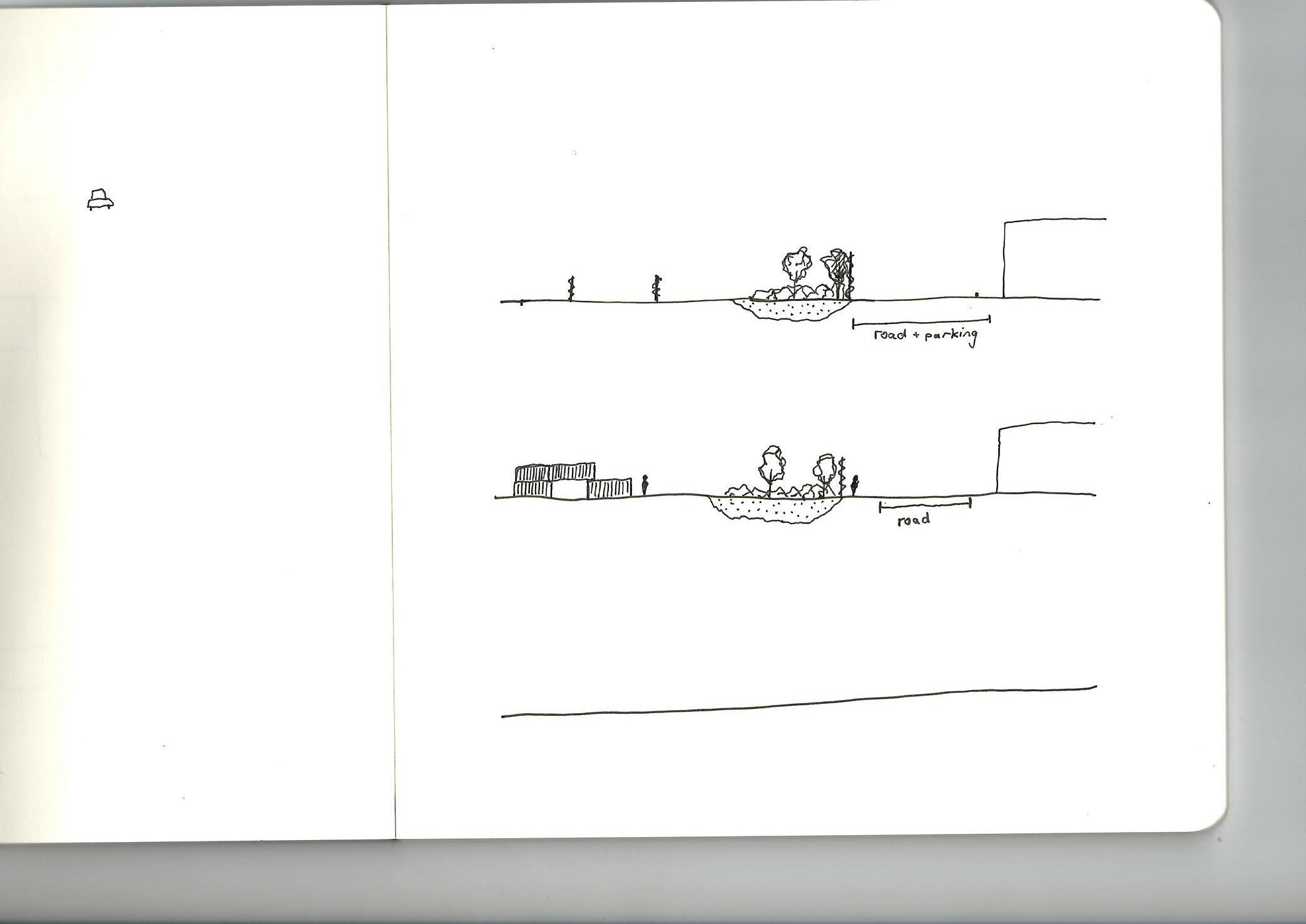

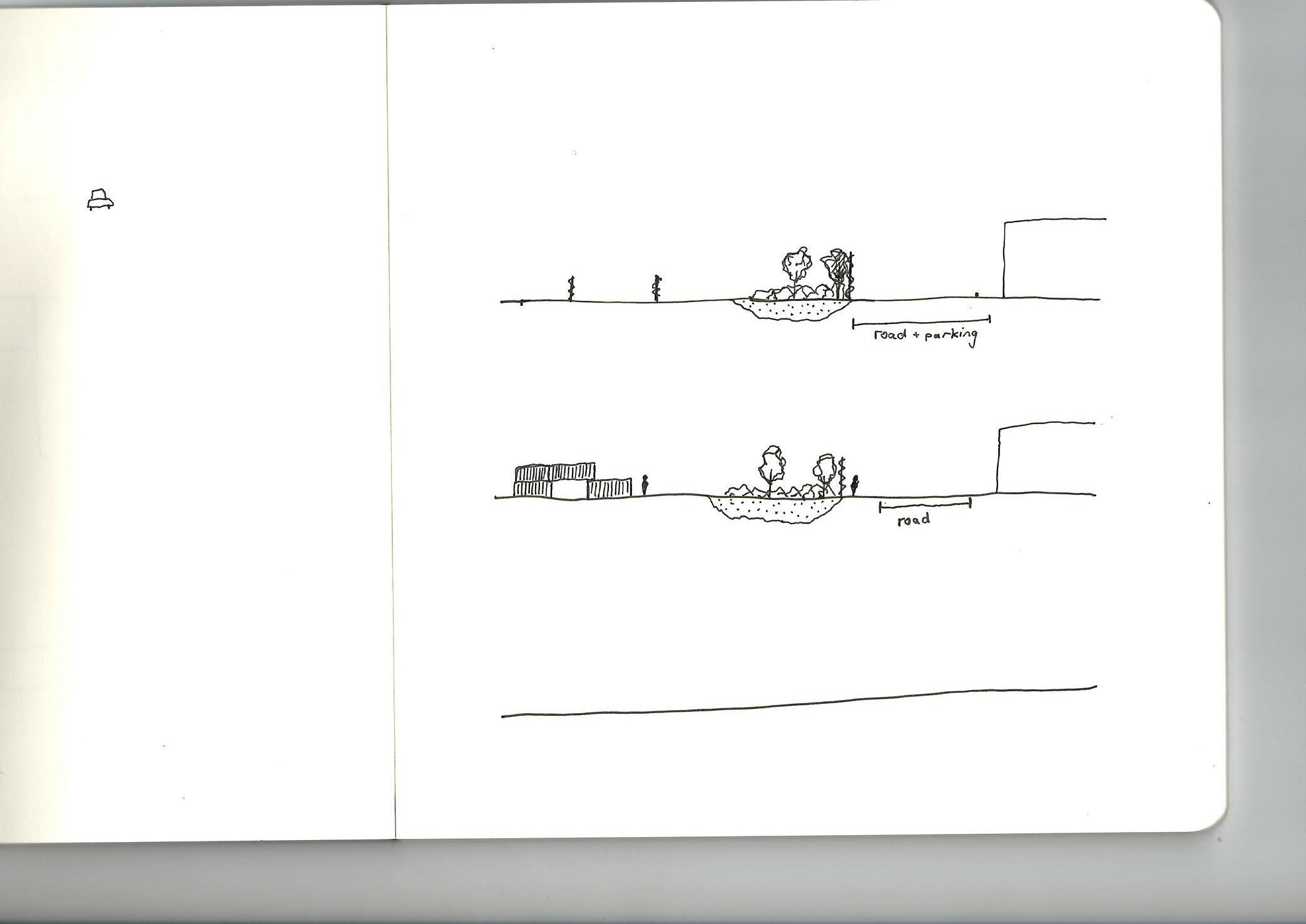

The following analysis looked at the site and it’s context through the lens of this principle

• Sydney Harbour’s first connected headland (outside cbd)

• Site is located in a ‘transition’ zone

• Needs to balance both local and regional scale activities

Population

Median age

Australian born

non - English

language households

Home owners

Renters

Lessons from Ijburg, Amsterdam

• Neighbourhood facilities did not serve as places of encounter between residents of different tenure types

• Neighbourhood facilities catered to more affluent residents

• Minority residents missed the lack of group specific facilities in the neighbourhood

• Playgrounds and other public spaces in the neighbourhood became unofficially segregated

Key

https://theglobalgrid.org/the-challenges-of-a-dutch-inclusive-neighborhood/ https://www.abs.gov.au/census

• Lack of public open space within the immediate catchment zone

• Great demand exists in Balmain for public open space

• The connecting of the site to the rest of Sydney through metro will only increase demand for public space

• A balance needs to be achieved by providing quality public space that is adequate for both locals and regional visitors

1.2km-5minsbybike

Gorbals redevelopment

• Glasgow, Scotland

• 1.4km from city

• 46 ha site

• Successful mixed tenure neighbourhood

• Former housing estate

• Skarpnack, Stockholm

• 8.1km from city

• 36 ha site

• Mostly residential development

• Streets and public spaces designed before the buildings

• Fullrigaren, Malmo

• 1.8km from city

• 16 ha site

• Former waterfront industrial site

• Streets and public spaces prioritised in design process

• Almere, Netherlands

• Small scale city centre

• 16 ha site

• Waterfront site

• Mixed use development

• Streets and public spaces prioritised in design process, but has mixed success

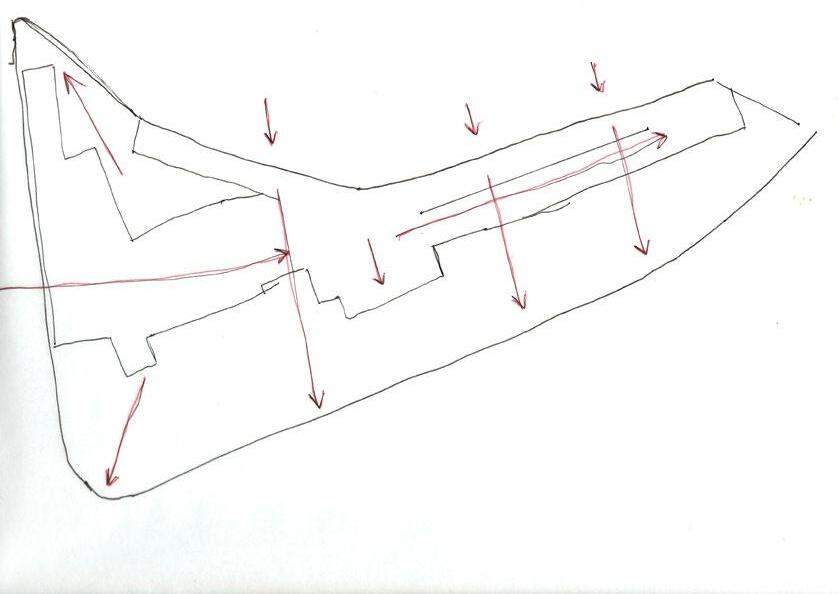

The beginning of the third term looked at how minimal changes to the site could create a greater change in fostering a socially sustainable community

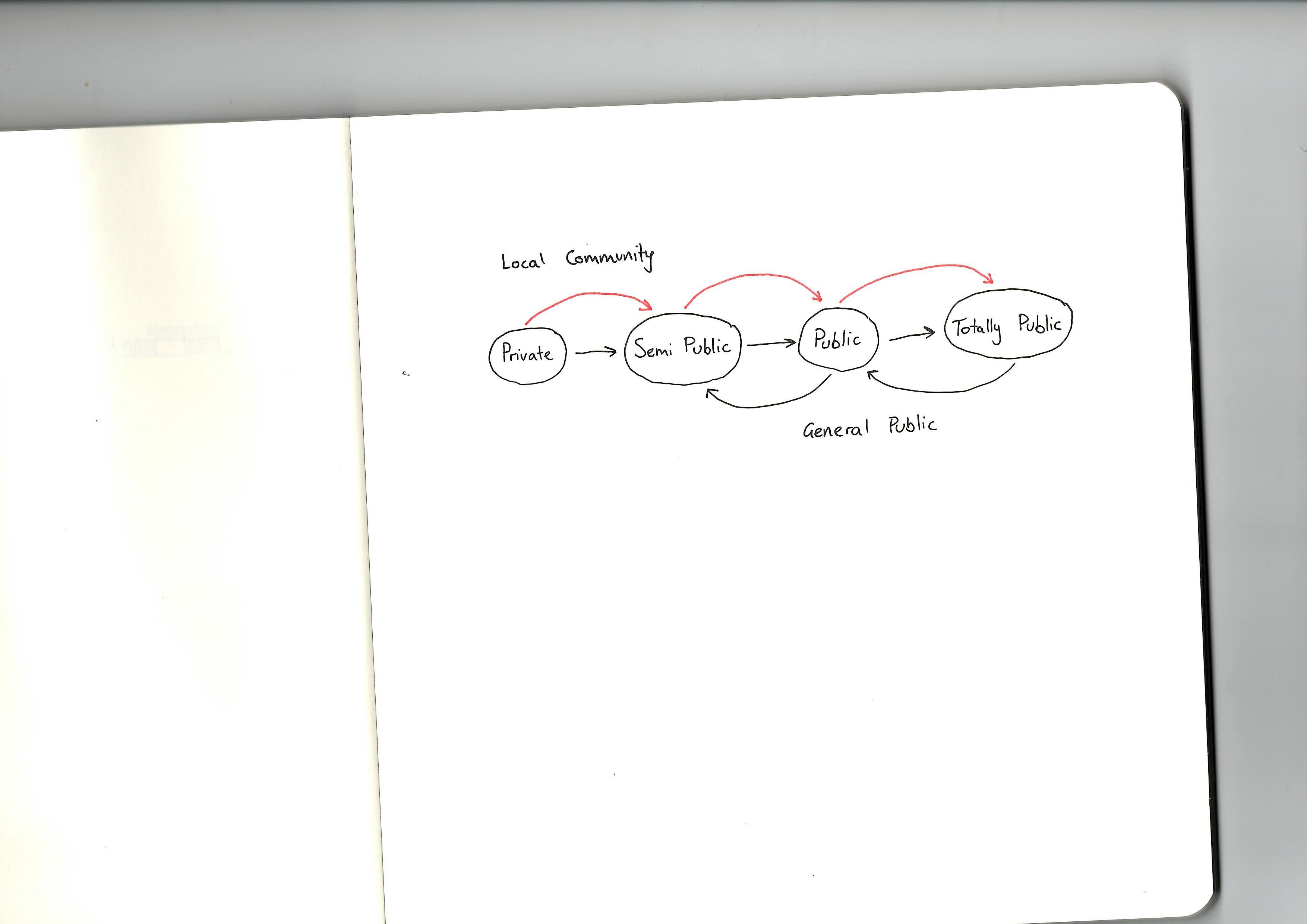

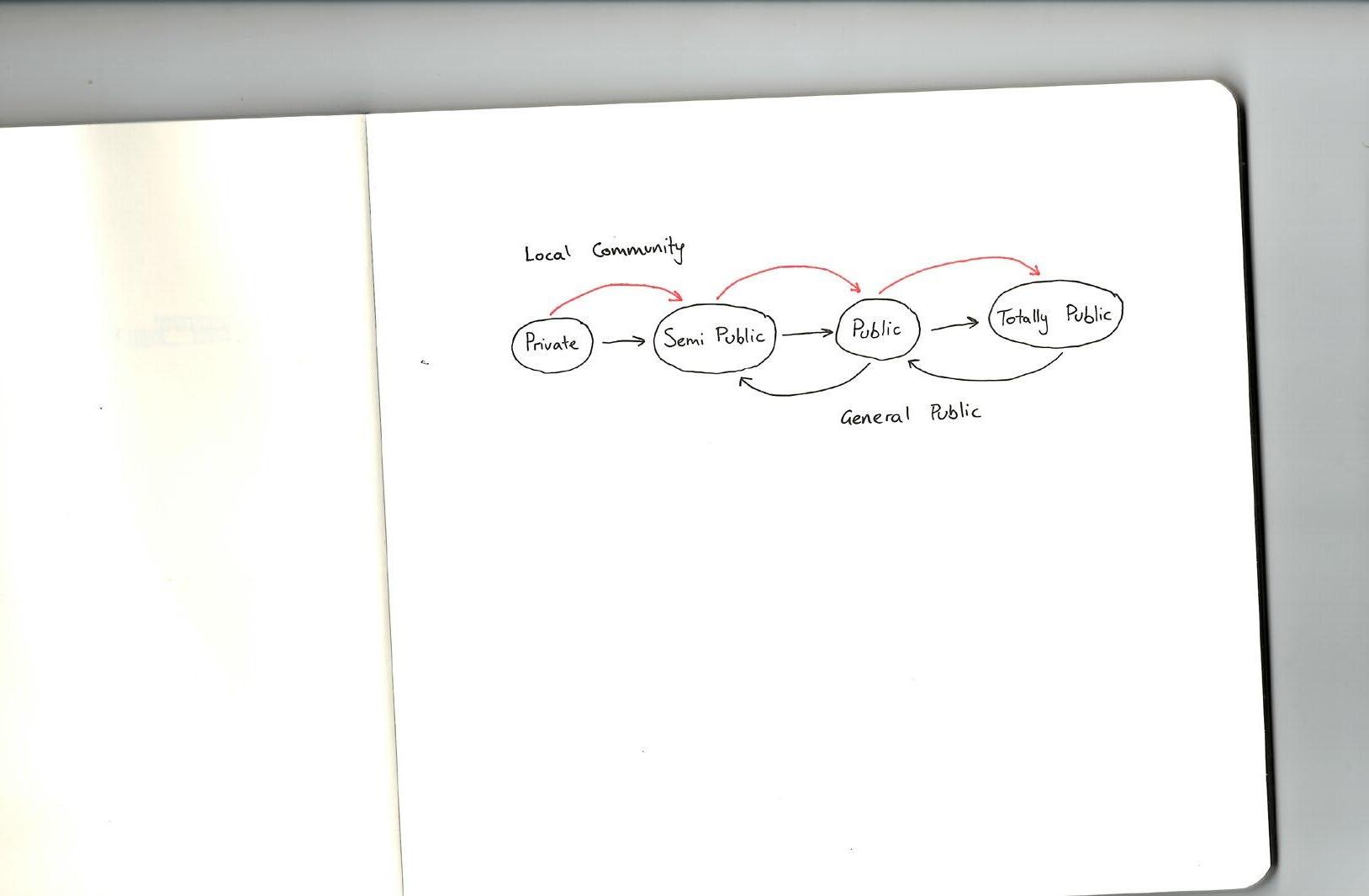

Local community can access all levels of public space

On the other hand other hand the general public should have limited access to local scale public spaces

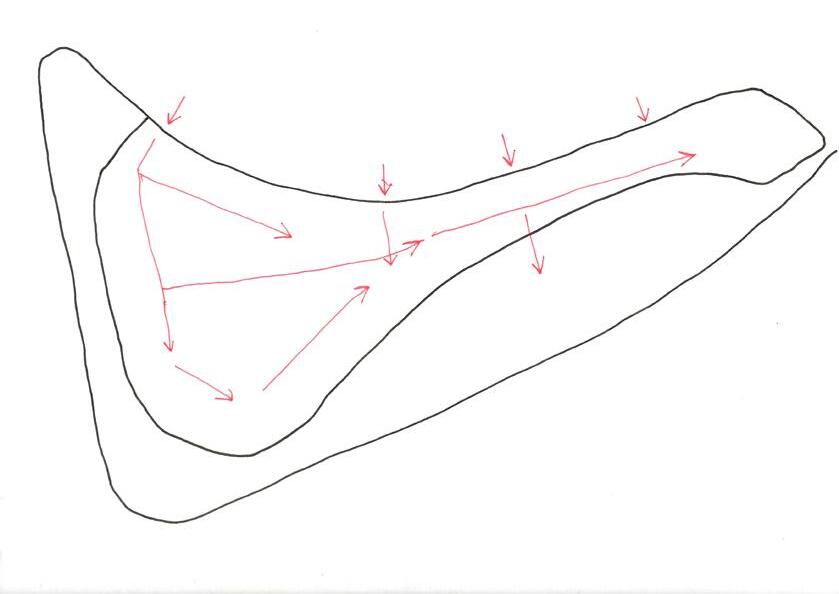

Analysis of the character zones on site. The aim was to identify where changes in atmosphere of public space occurred

This piece of analysis looked at how physical barriers affected character zones

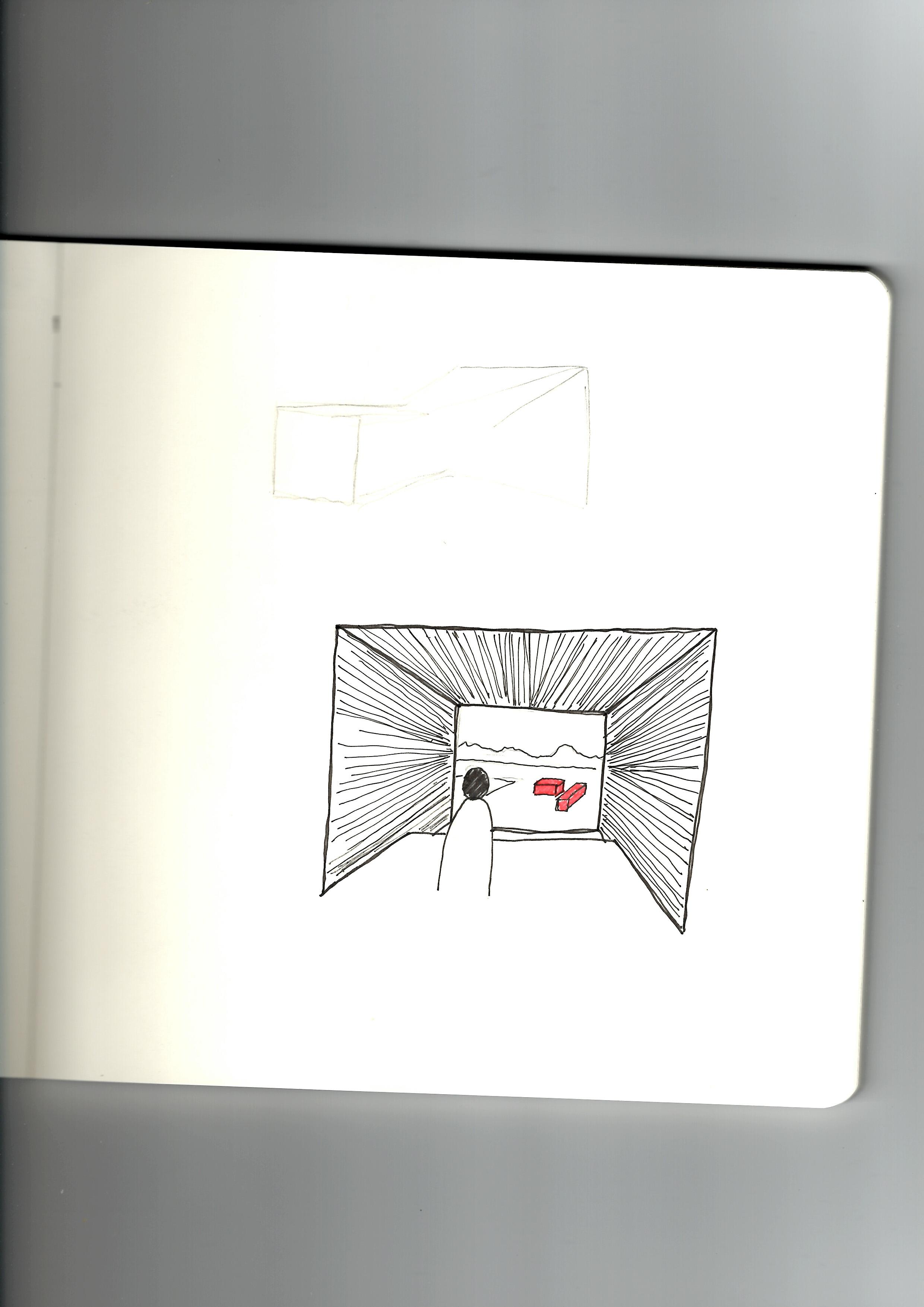

Finally an analysis of sightlines into the ‘city scale’ space was conducted

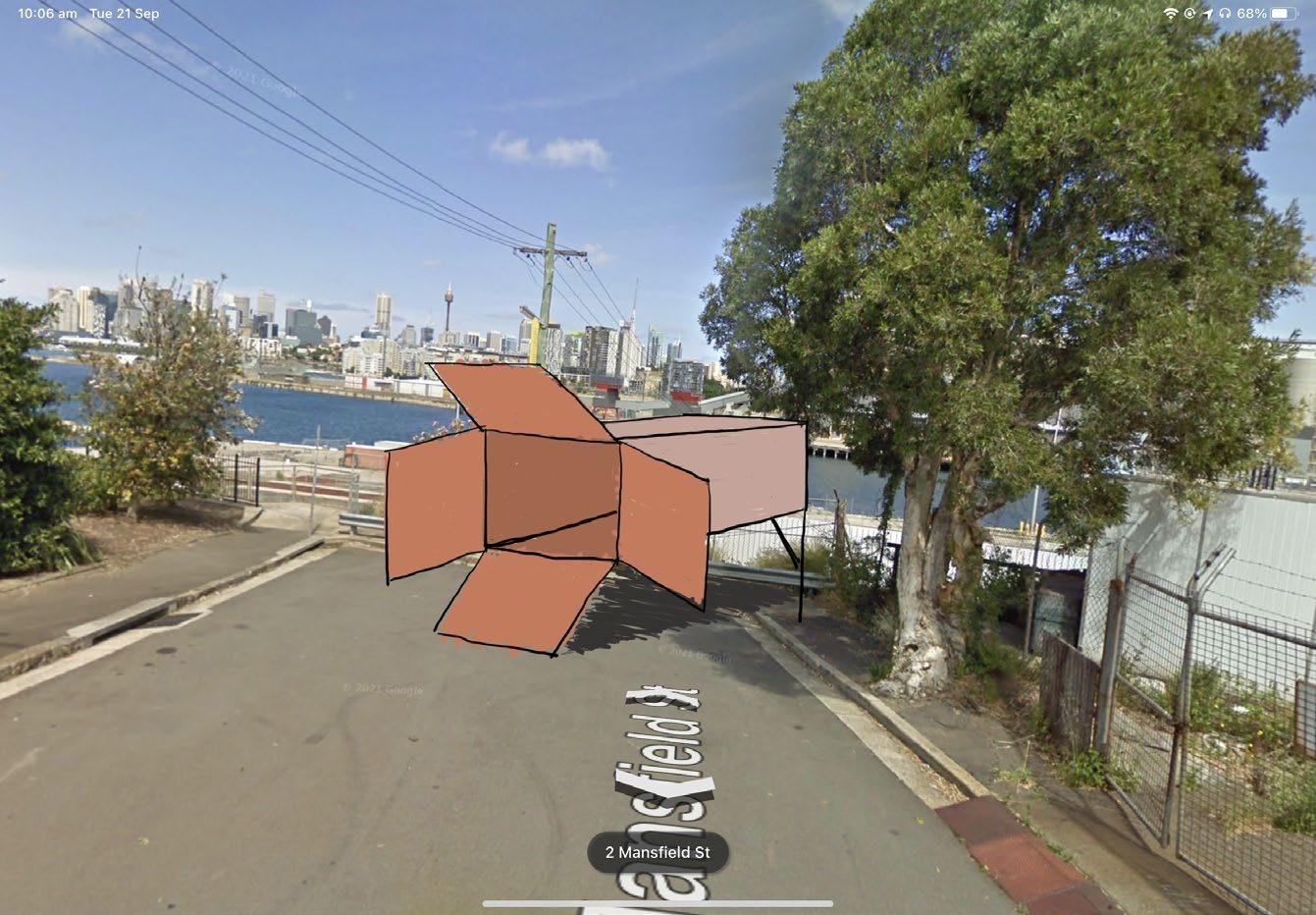

The resulting idea was to create a series of temporary lookouts which would frame a temporary public space, seeking to draw residents into a space that was previously off limits.

After 6 months

A ‘social hub’ is established to host community events and act as a centre for community discussion on the future of the public space

Inspiration was taken from other container ‘parks’ which started off as temporary and eventually became permanent as a result of their popularity.

After 2 years

The number of temporary structures on site may increase according to demand for more activity

• Fences prevent access to White Bay and the adjacent road lacks activation

6 months

• Fences are removed and White Bay is made partially accessible, amidst other development

• Toxic sites remain fenced off during the phytoremediation process

• On road parking is removed in favour of pedestrianisation

2 years

• The scope of the public space is expanded

• Fencing around formerly toxic sites is removed

• Road capacity is further reduced

The site continues to develop in a similar vein

The activity and program disappears to be replaced by something else

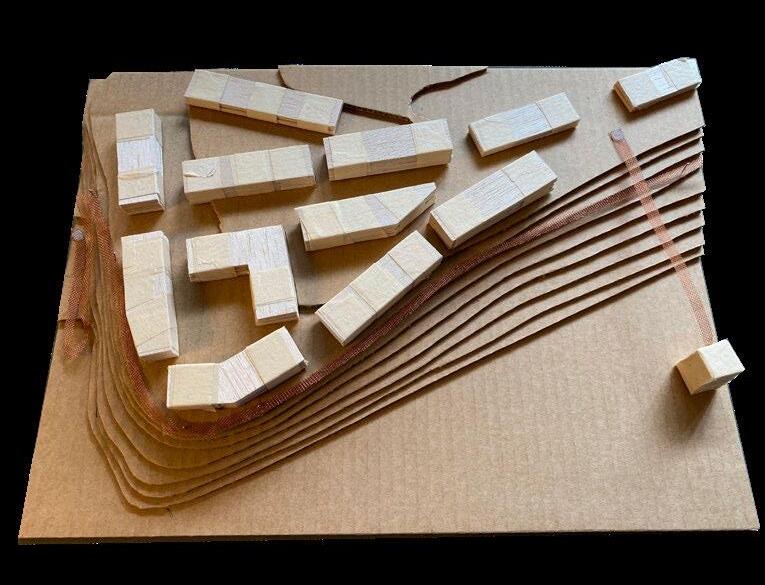

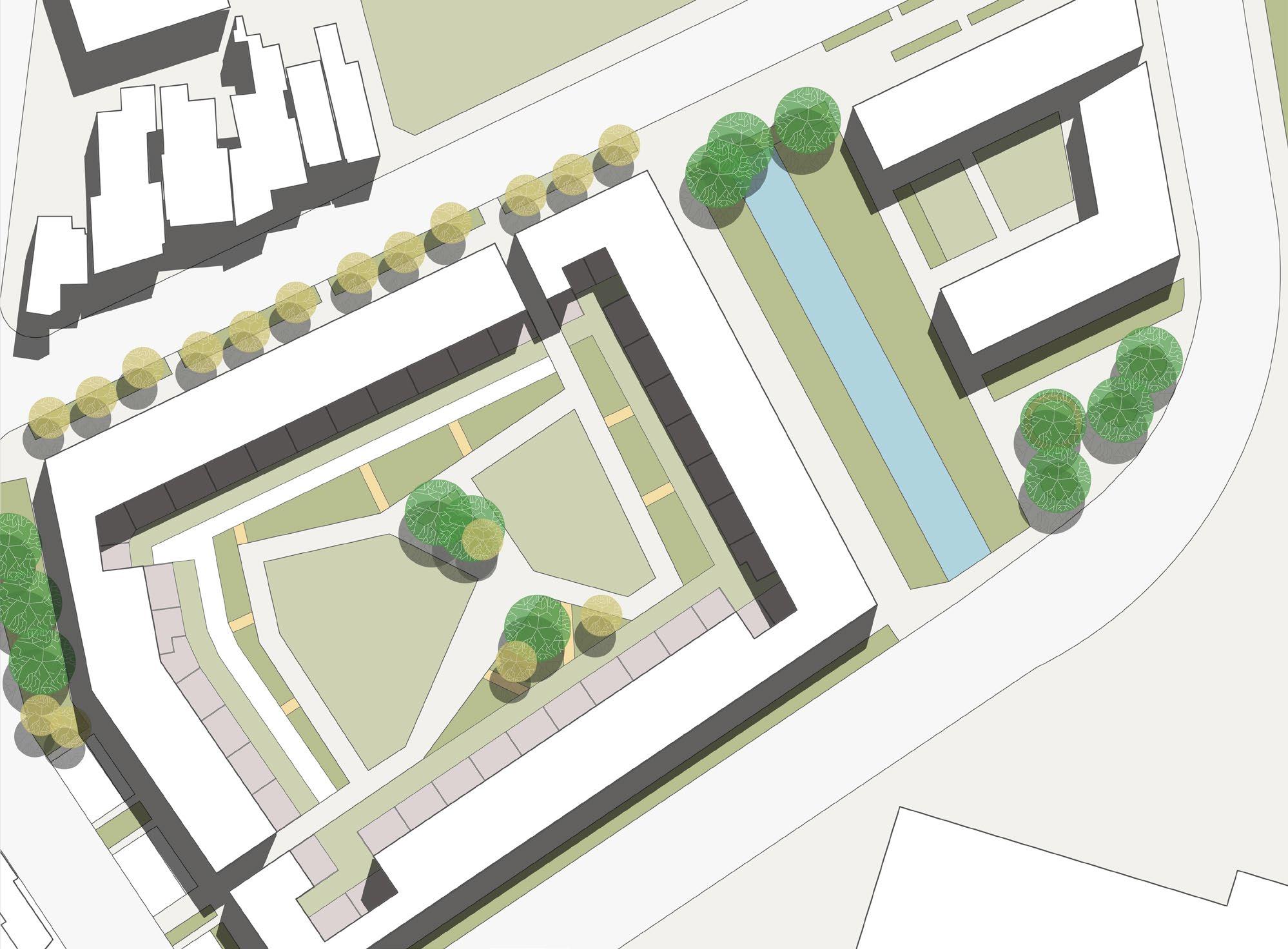

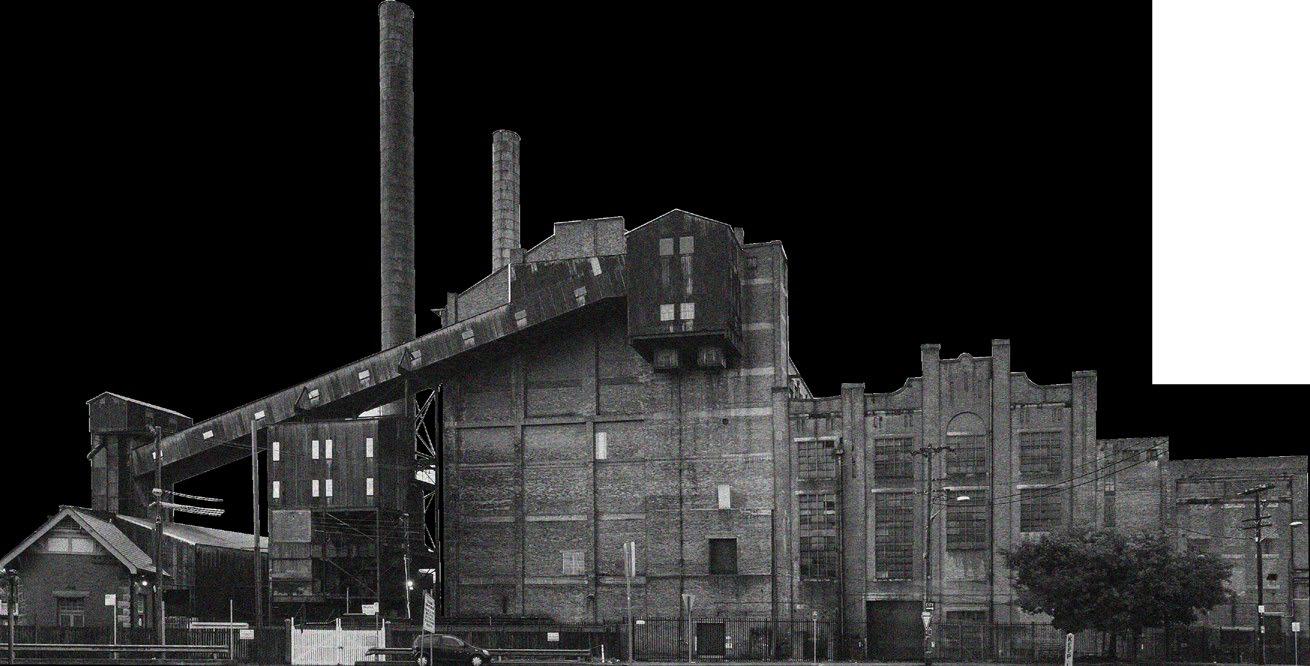

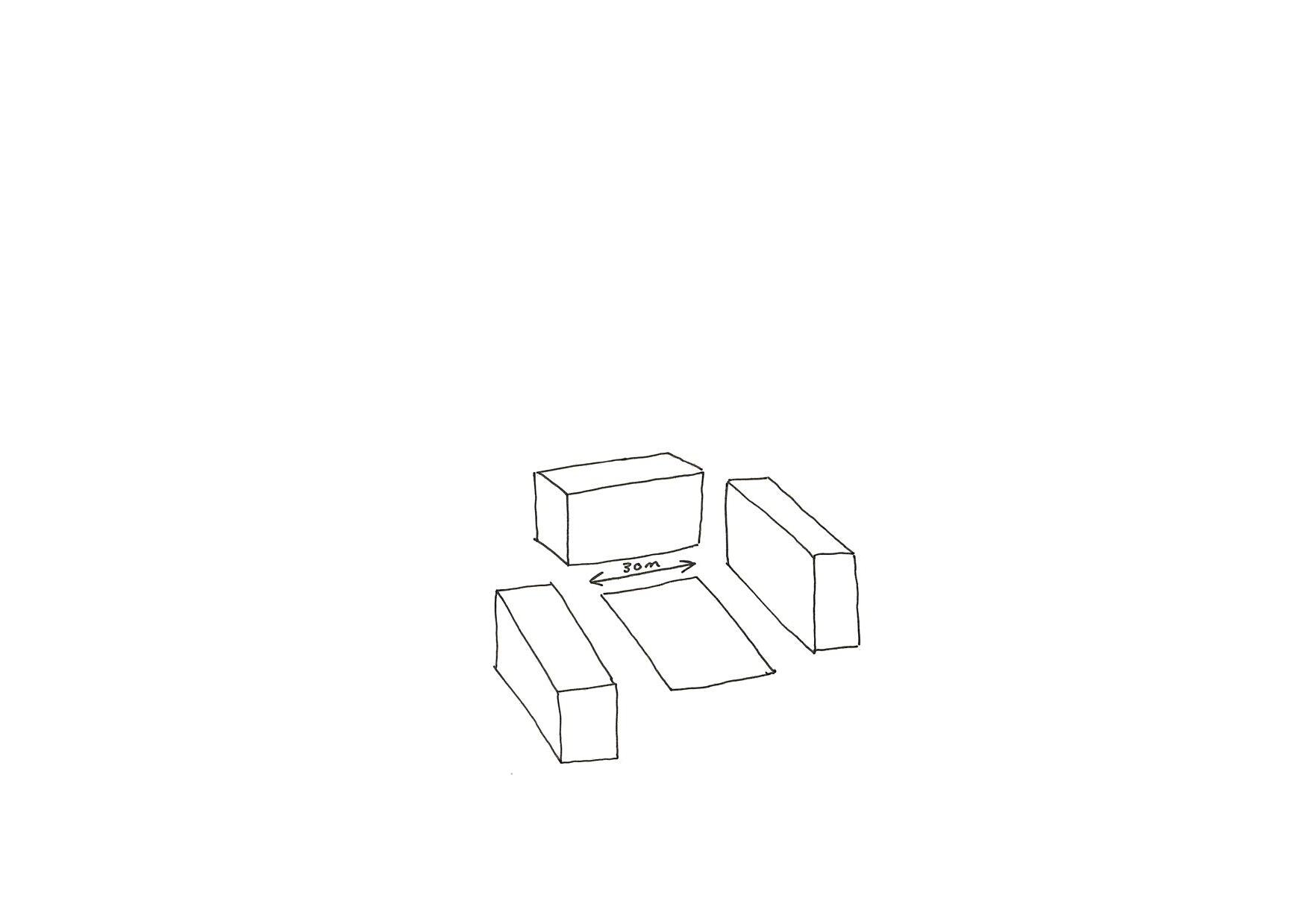

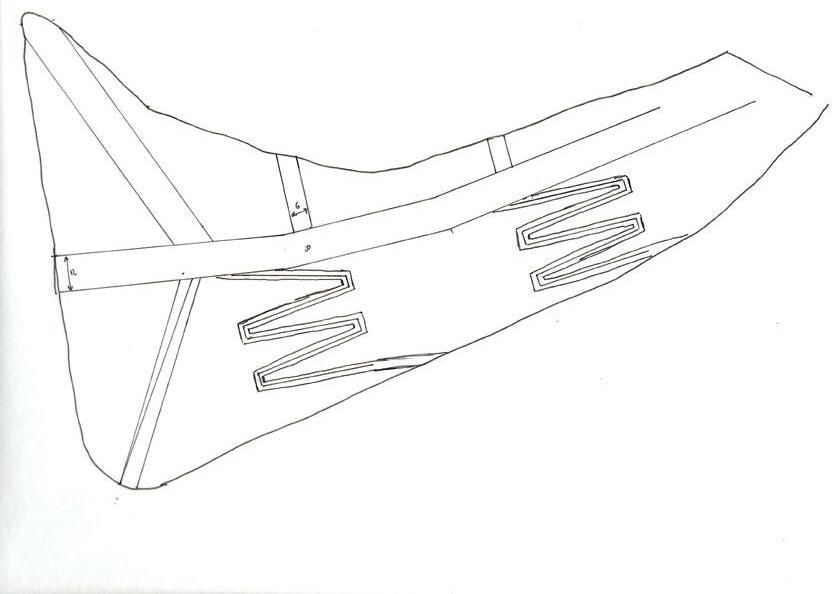

This stage of the year was dedicated to developing a series of phasing plans which would map out the next 30 years of development around the White Bay power station. A larger focus was put on designing a mixed tenure neighbourhood, while also balancing the need to clean a contaminated site.

What are mixed tenure neighbourhoods? Mixed neighbourhoods are a type of neighbourhood used by urban planners to combat a rise in segregated neighbourhoods within a city. Through the creation of neighbourhoods of varying tenure types (eg. home owners or social renters), mixed tenure neighbourhoods combat segregation by attempting to foster greater social cohesion (Roberts 2007). Mixed tenure neighbourhoods have begun to form the backbone of planning and housing policies for many European countries (Tersteeg & Pinkster 2015).

Why is this important for the Bays? The NSW government’s latest proposal for the Bays states a desire to ‘…ensure a diversity of types and tenure, including affordable housing.” (Department of Planning, Industry and Environment 2021). The Bays will be the NSW government’s second attempt at creating a successful mixed tenure neighbourhood after the controversial Waterloo redevelopment. While the creation of a successful mixed tenure neighbourhood is a result of a number of factors, landscape architecture and the design of public space can play a large role.

How can the design of public space make an impact? The design and use of public space plays a significant role in encouraging social cohesion within mixed tenure neighbourhoods. Public spaces provide areas in which different groups encounter each other and can determine the nature of the encounter. Sharing public facilities can have positive effects, however it can also have a negative effect if spaces become segregated (Tersteeg & Pinkster 2015). Gehl highlights the significance of the public realm stating that public spaces are crucial in facilitating the ‘bumping into strangers’ (Gehl 2011).

How can we create public spaces which facilitate encounters between strangers? Jan Gehl promotes the idea that design should look at city life, then city spaces and finally buildings to ensure the best outcomes for people. By prioritising city life on a human scale, greater cohesion can be fostered within communities (Gehl 2010). Shaftoe also supports this idea, asserting that the creation of ‘convivial spaces’ is the answer. Creating public space in which people feel comfortable in provides the greatest chance of fostering social cohesion (Shaftoe 2008 ). Design of public space must also take into account the ethnic and cultural diversity of mixed tenure neighbourhood. Public spaces must crucially provide something for everyone (Tersteeg & Pinkster 2015). As a new urban development, White Bay provides the opportunity to reorder our priorities in urban design.

Privacy facilitates greater security and engagement within communities

• Highly contaminated site

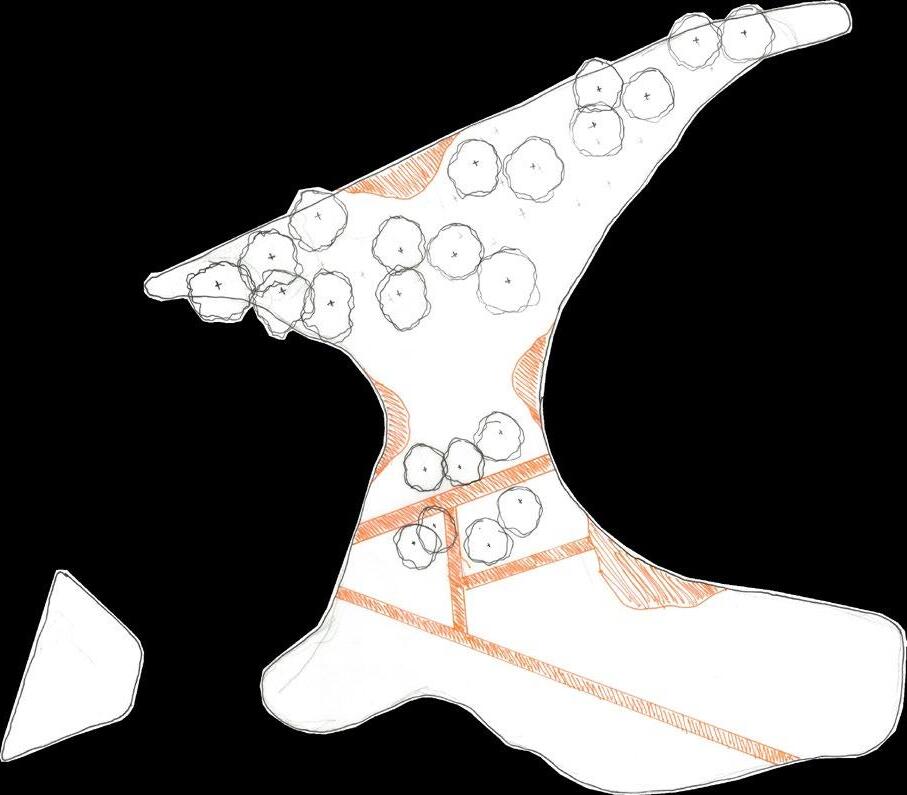

• Opportunity for phytoremediation processes to shape public space

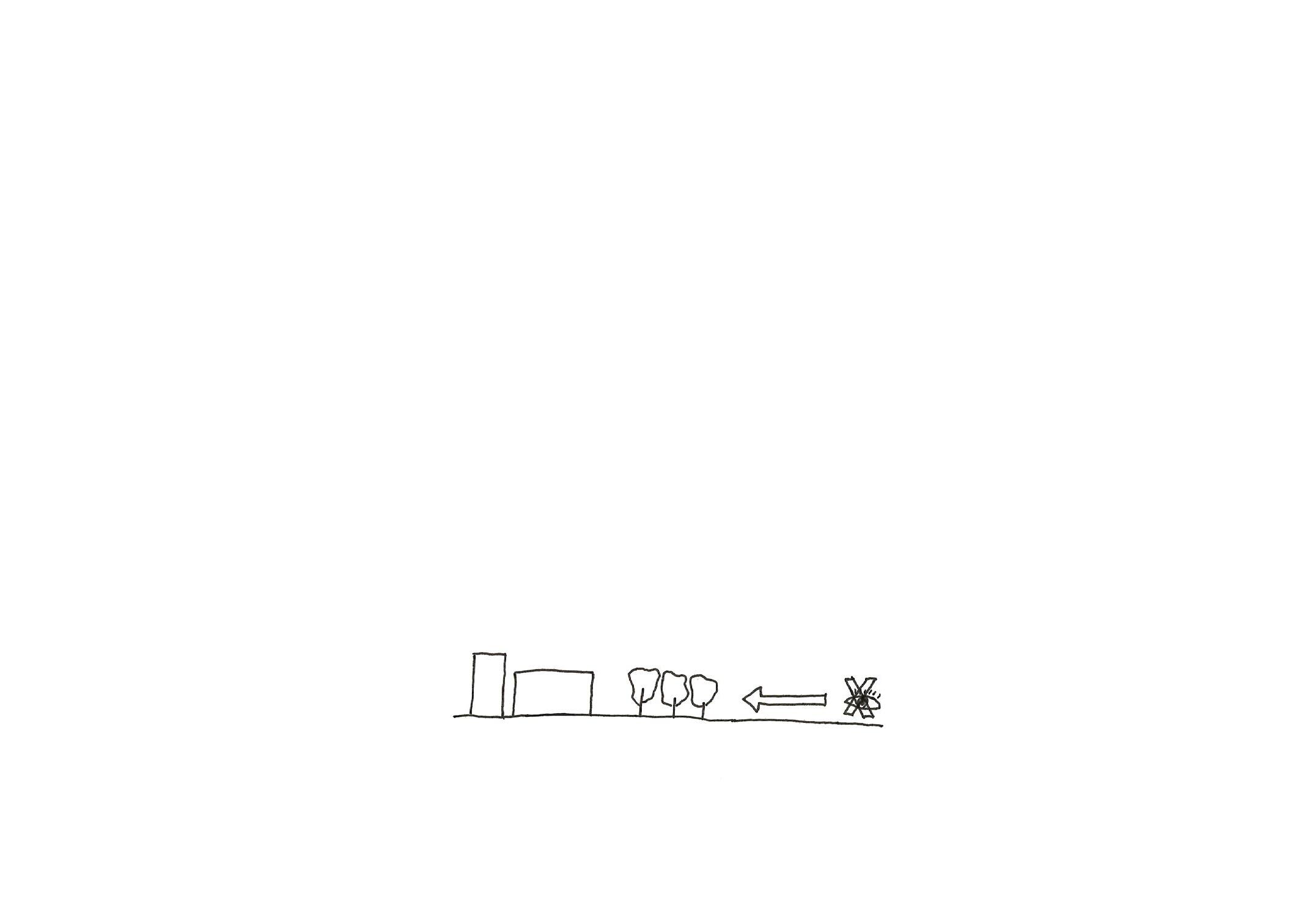

• Planting can also be manipulated to block views

Phytoremediation processes begin

Phytoremediation planting

Residential developments completed

Phase 2 of phytoremediation

Public spaces opened

Metro opens

Vegetation is managed according to events and time of year

Phytoremediation planting

Indicative summer cuttings

Metro station

Residential development is completed. Sightlines are established, providing a degree of privacy for residents

2050+ summer

During the summer months paths and extra public spaces are cut into the vegetation

Phytoremediation planting matures Public spaces opened up

Residential development complete Metro opens

Phase 2 of phytroremediation

Port no longer in use

Phytoremediation planting cut to open up public space

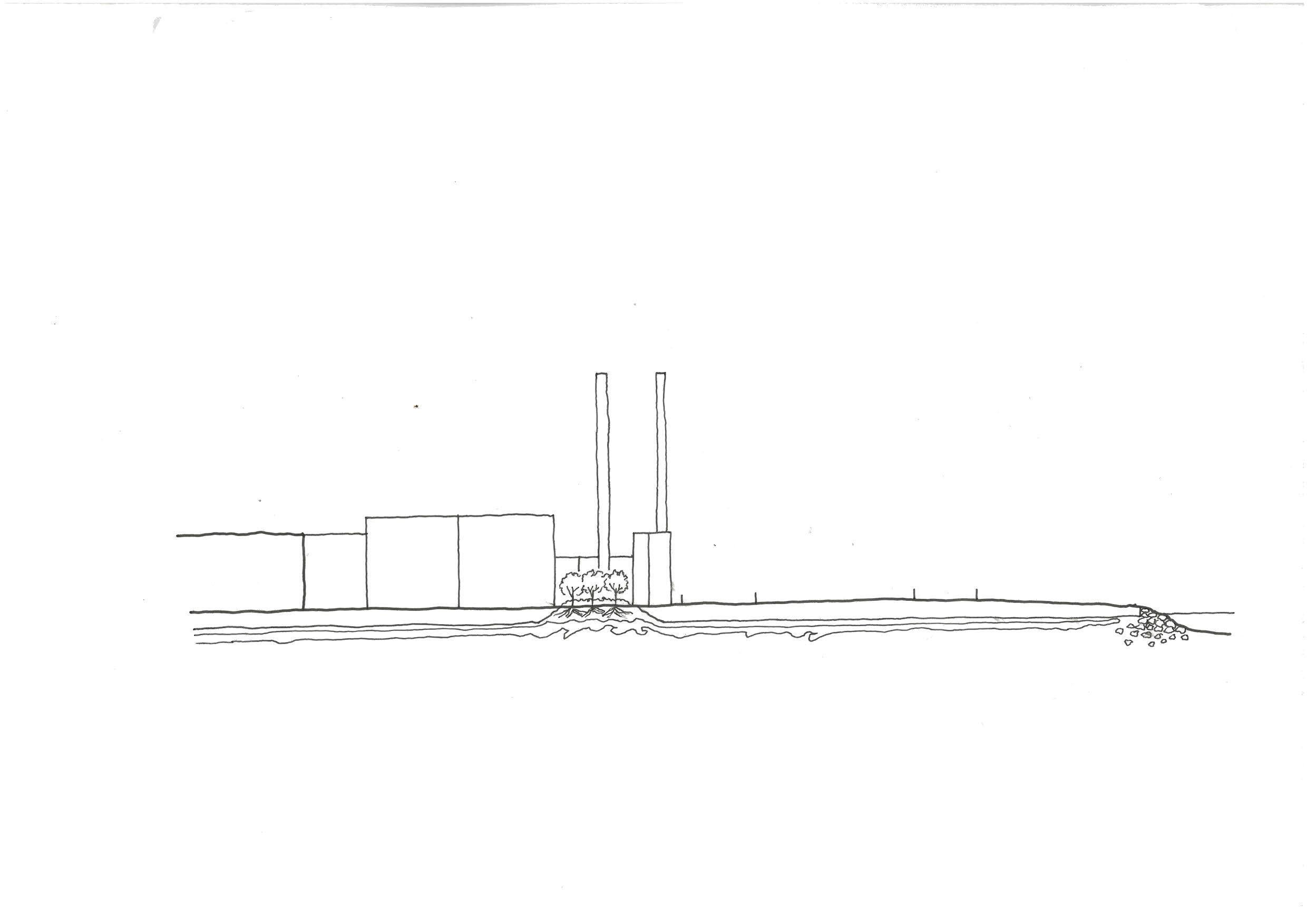

Site is completely fenced off from public

Concrete cap is broken in order to begin breaking down contaminants below

Building lots are demolished and phytoremediation planting begins to establish itself

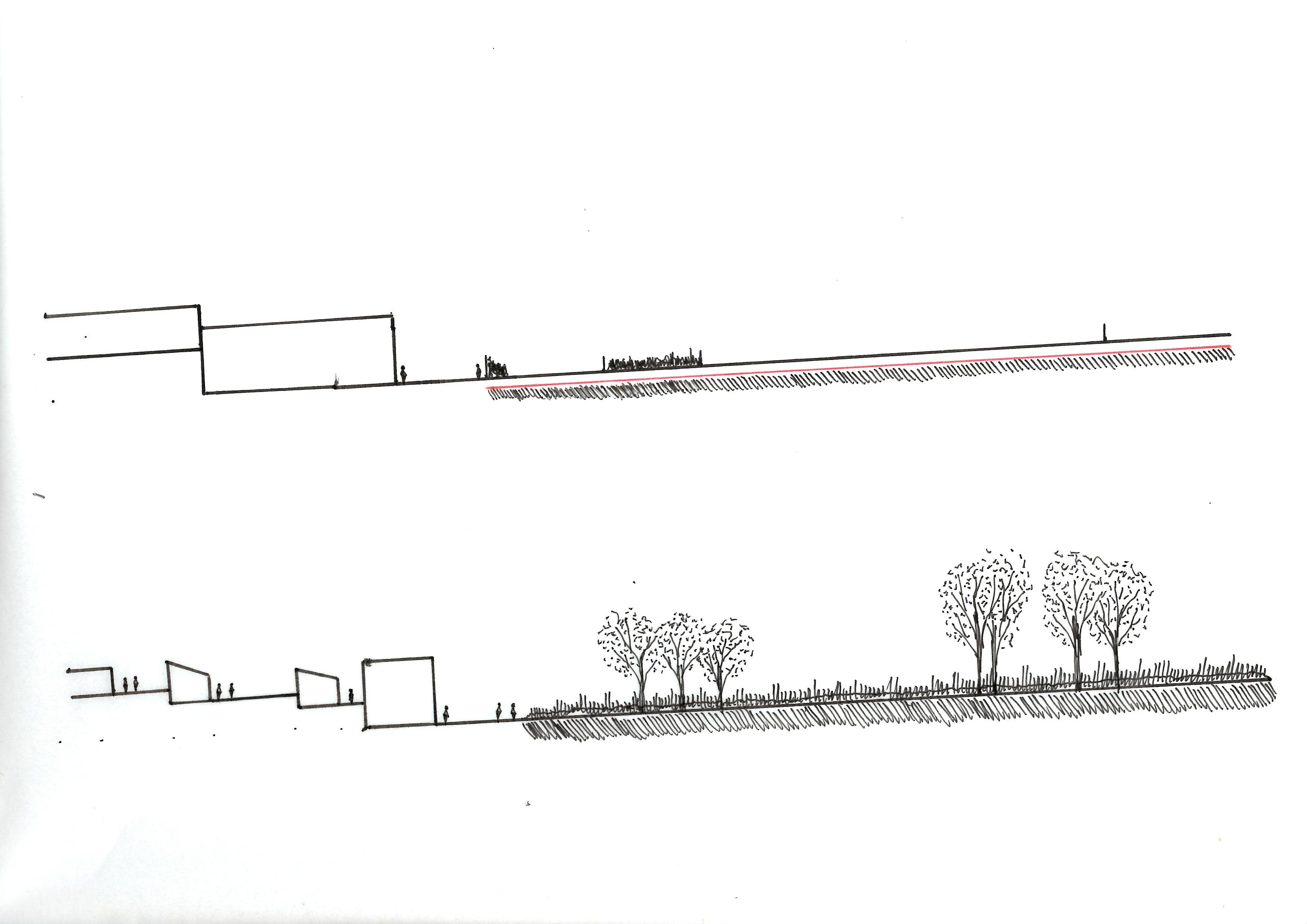

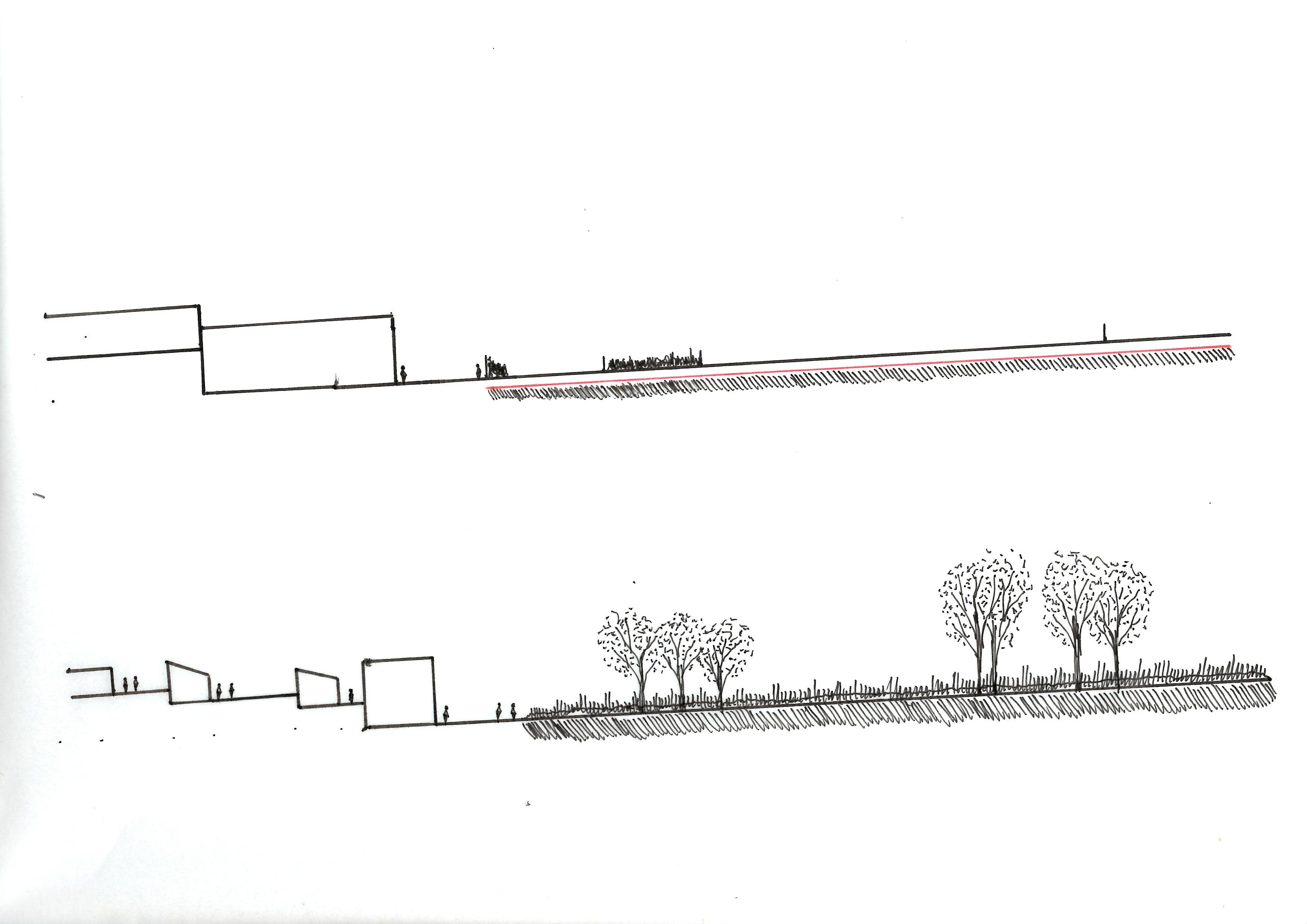

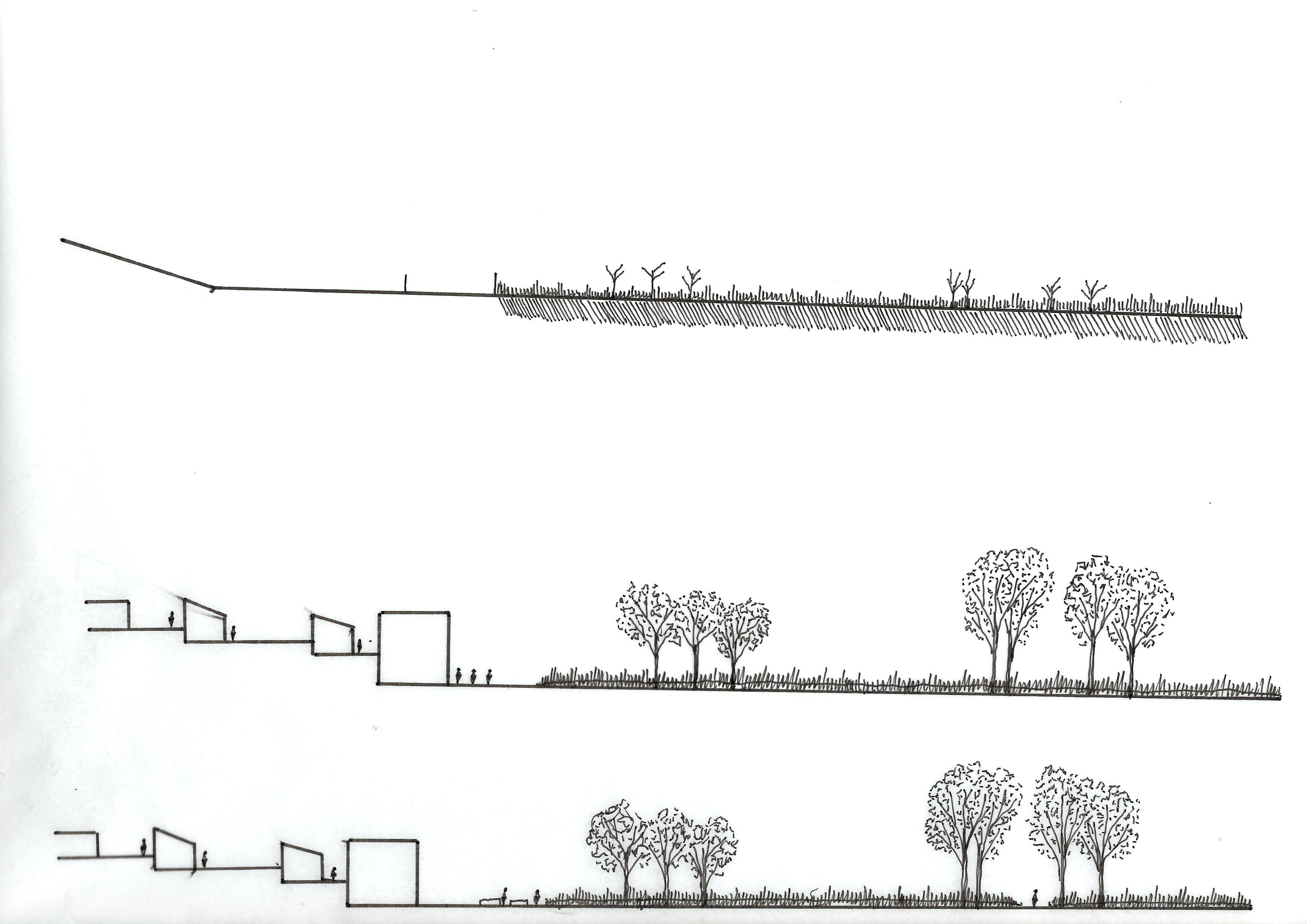

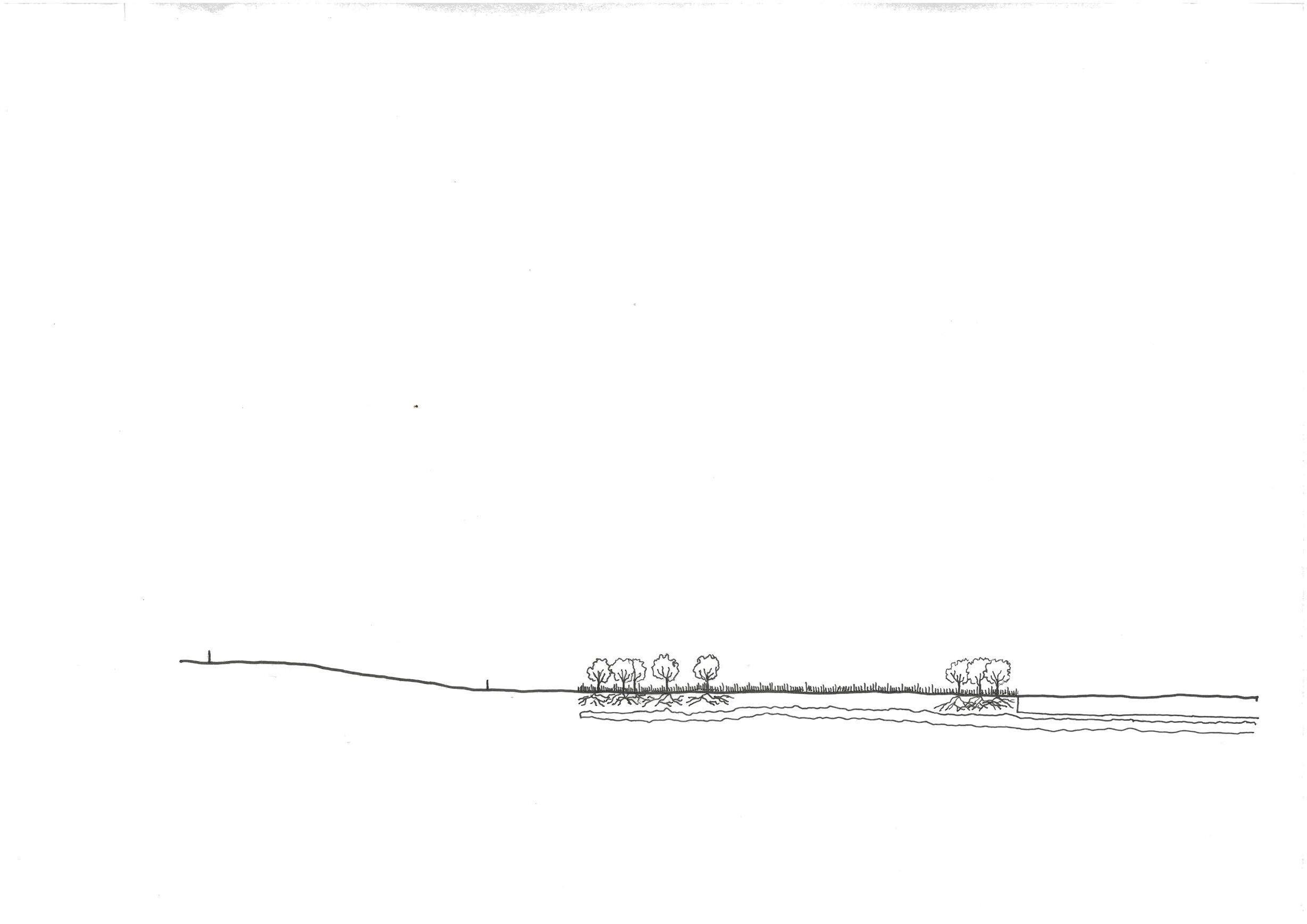

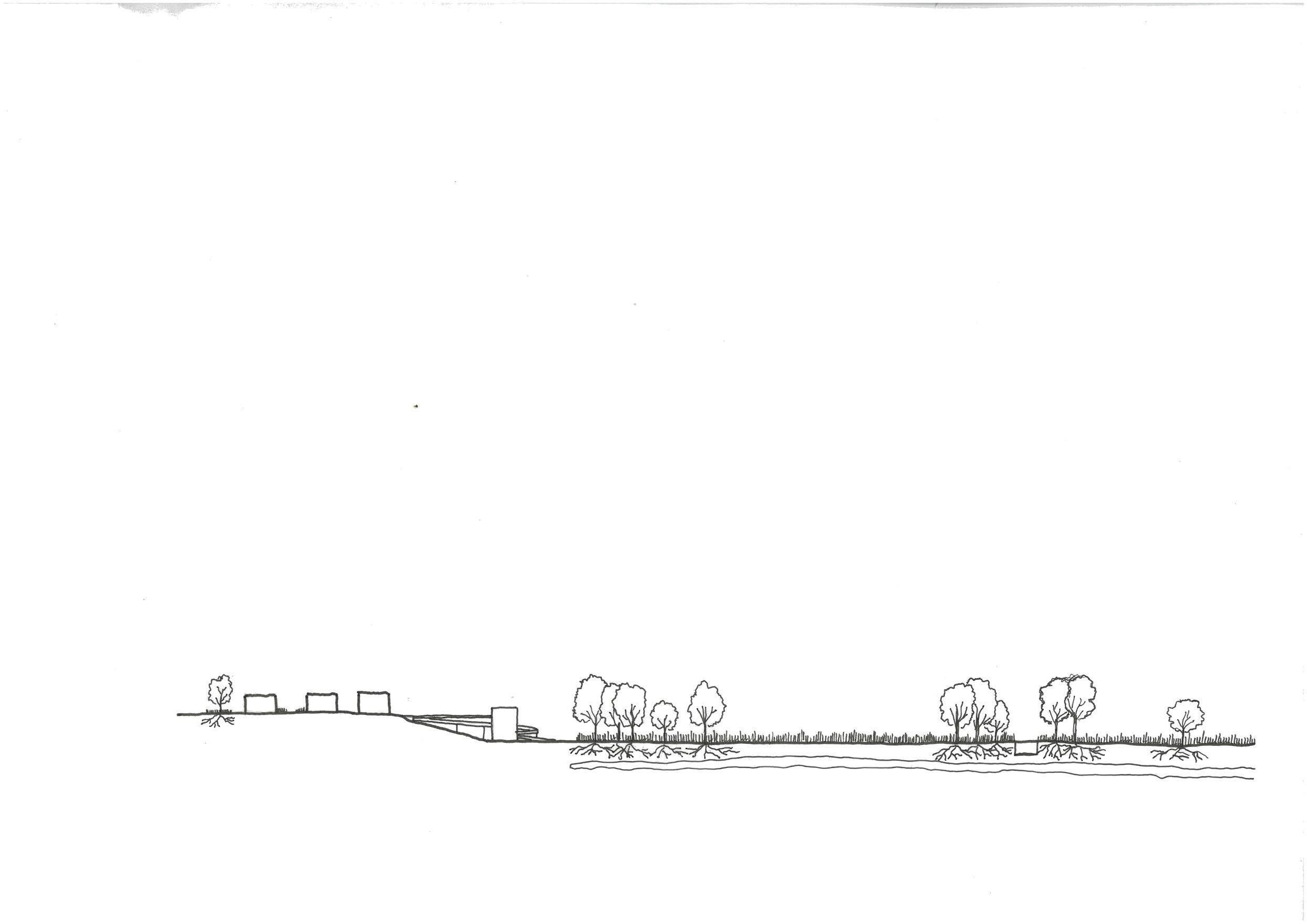

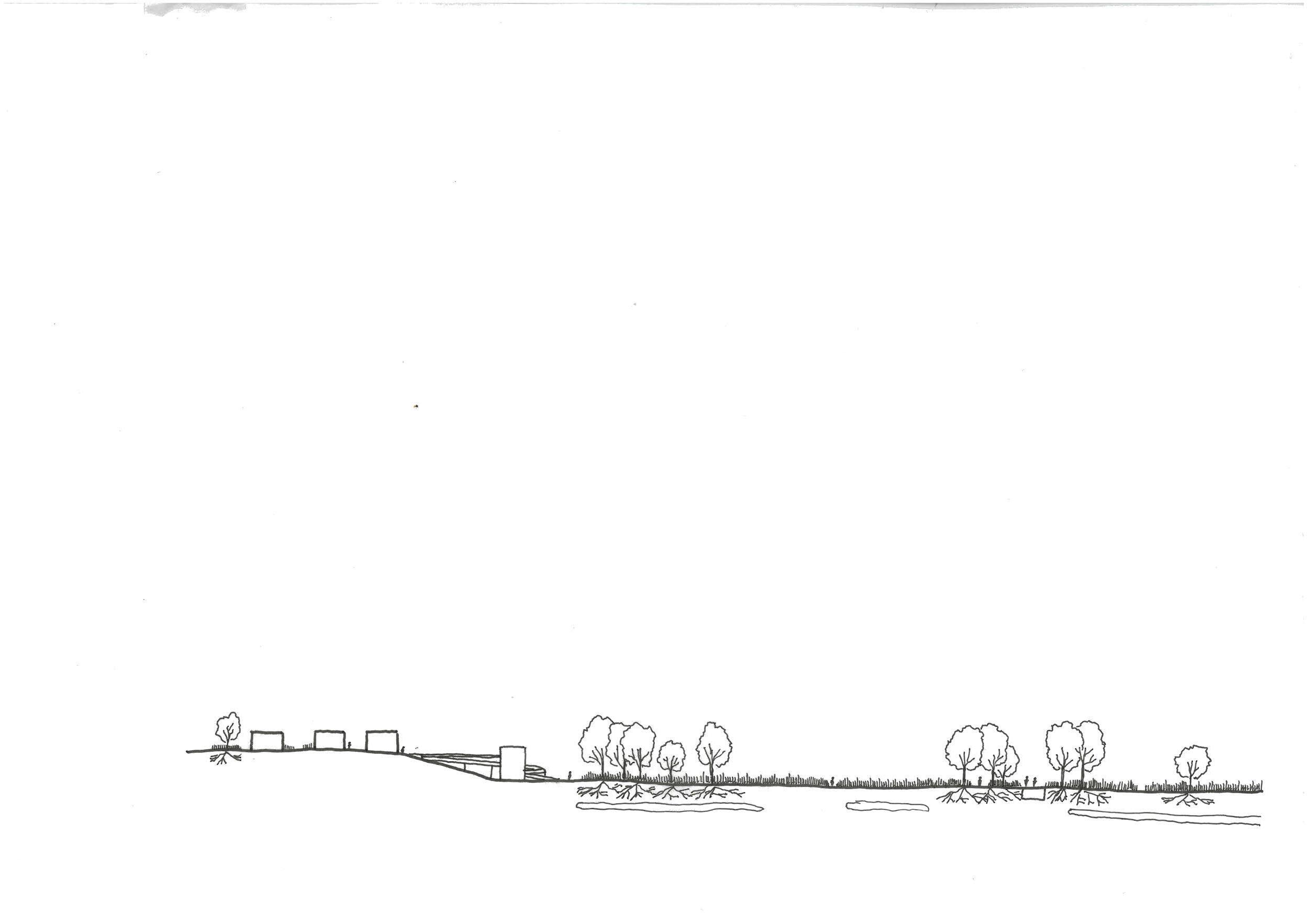

North - South section

Building lots remain under construction, while planting begins to form a visual barrier between Balmain and White Bay

East - West section

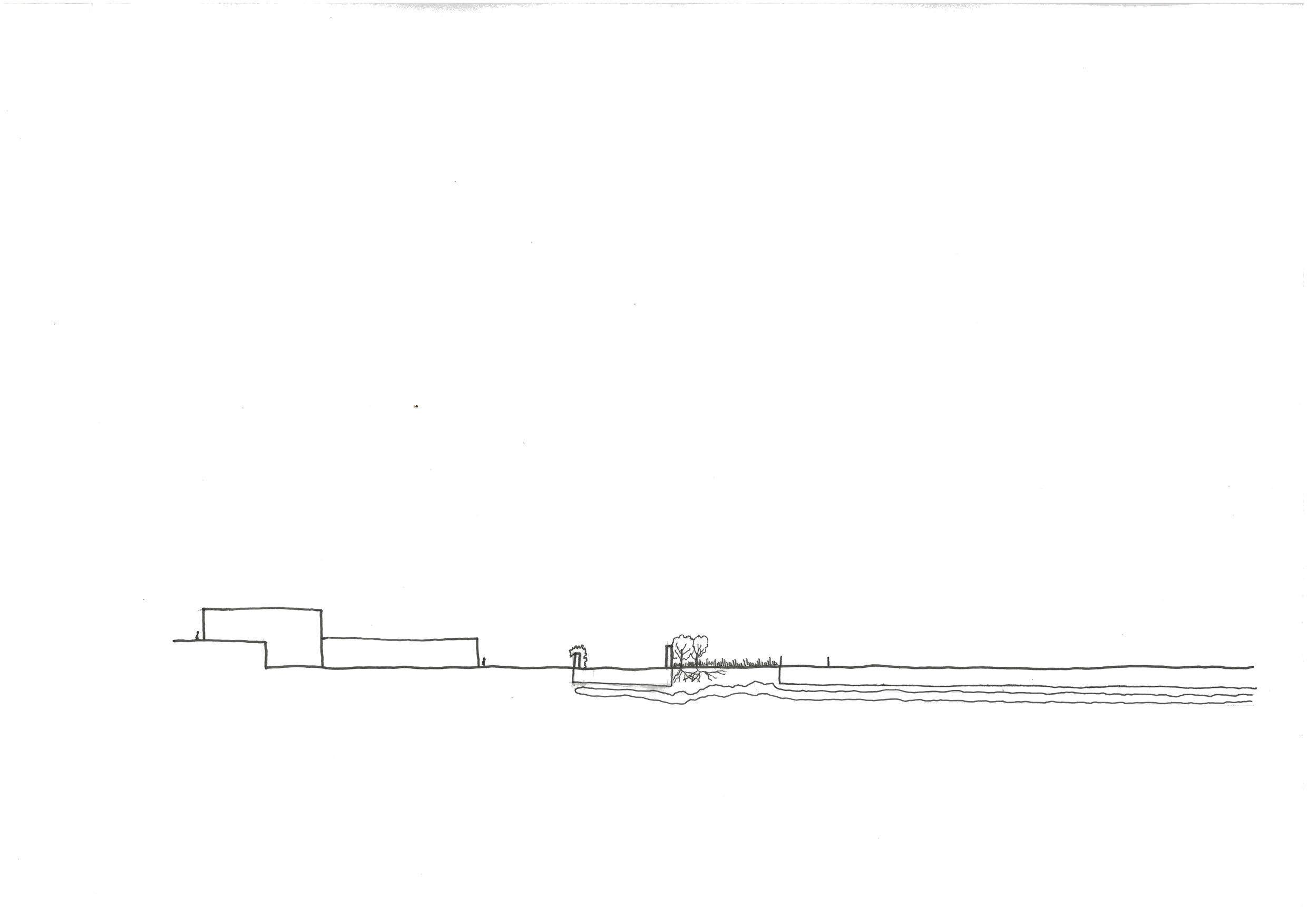

Edge condition with water is altered to allow visitors to interact with the water

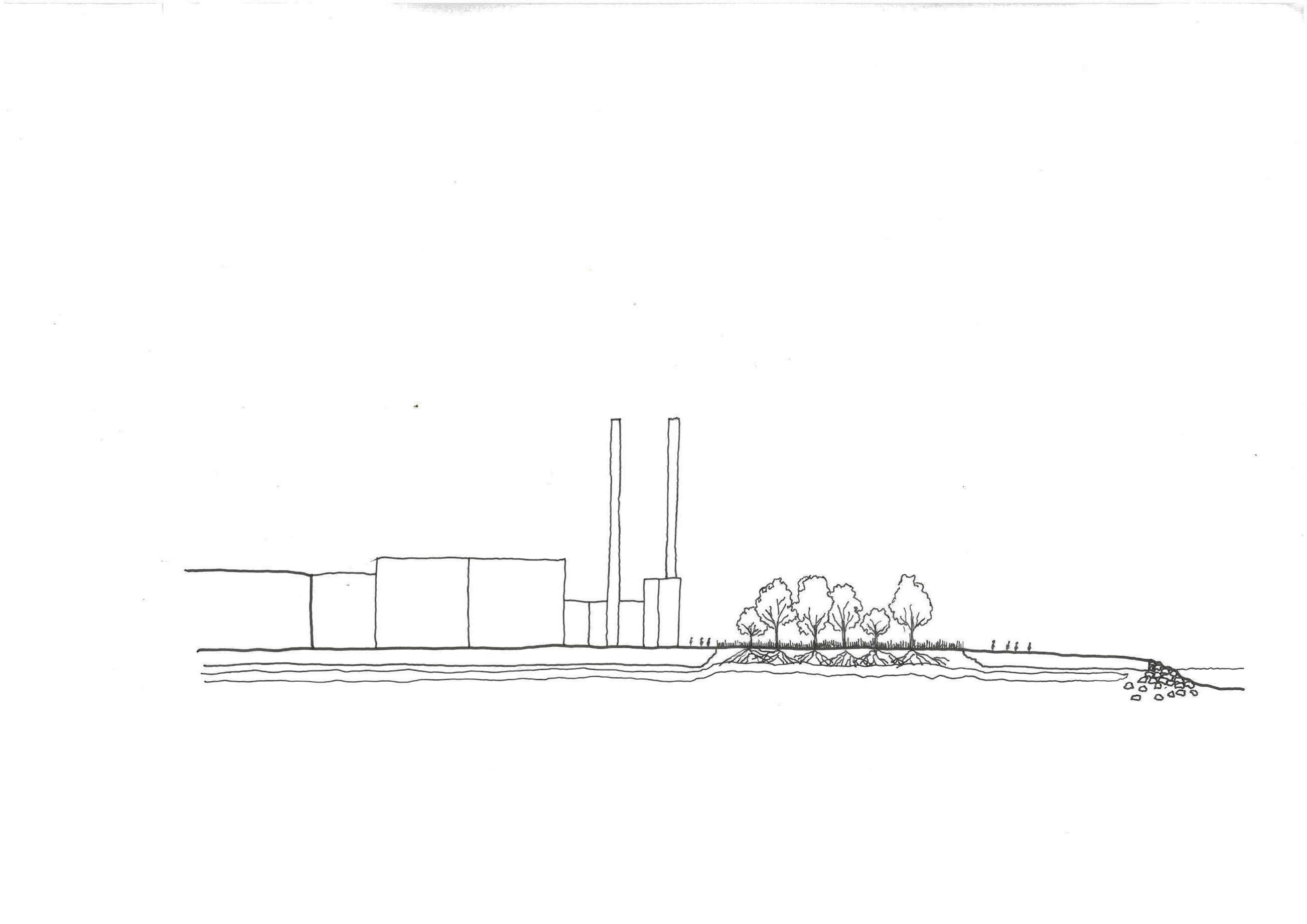

North - South section

Residential precincts are completed, alongside new access paths into White Bay

East - West section

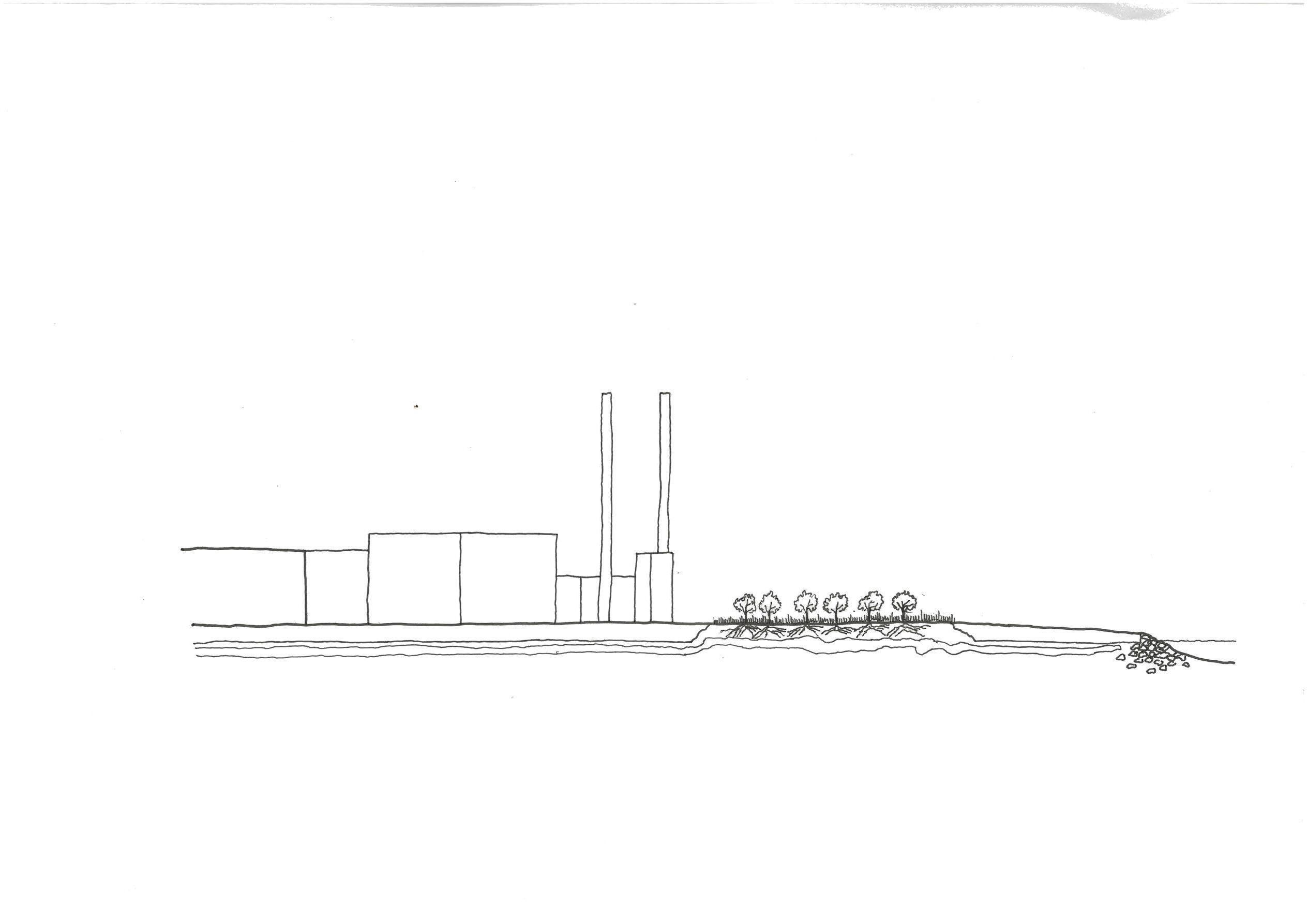

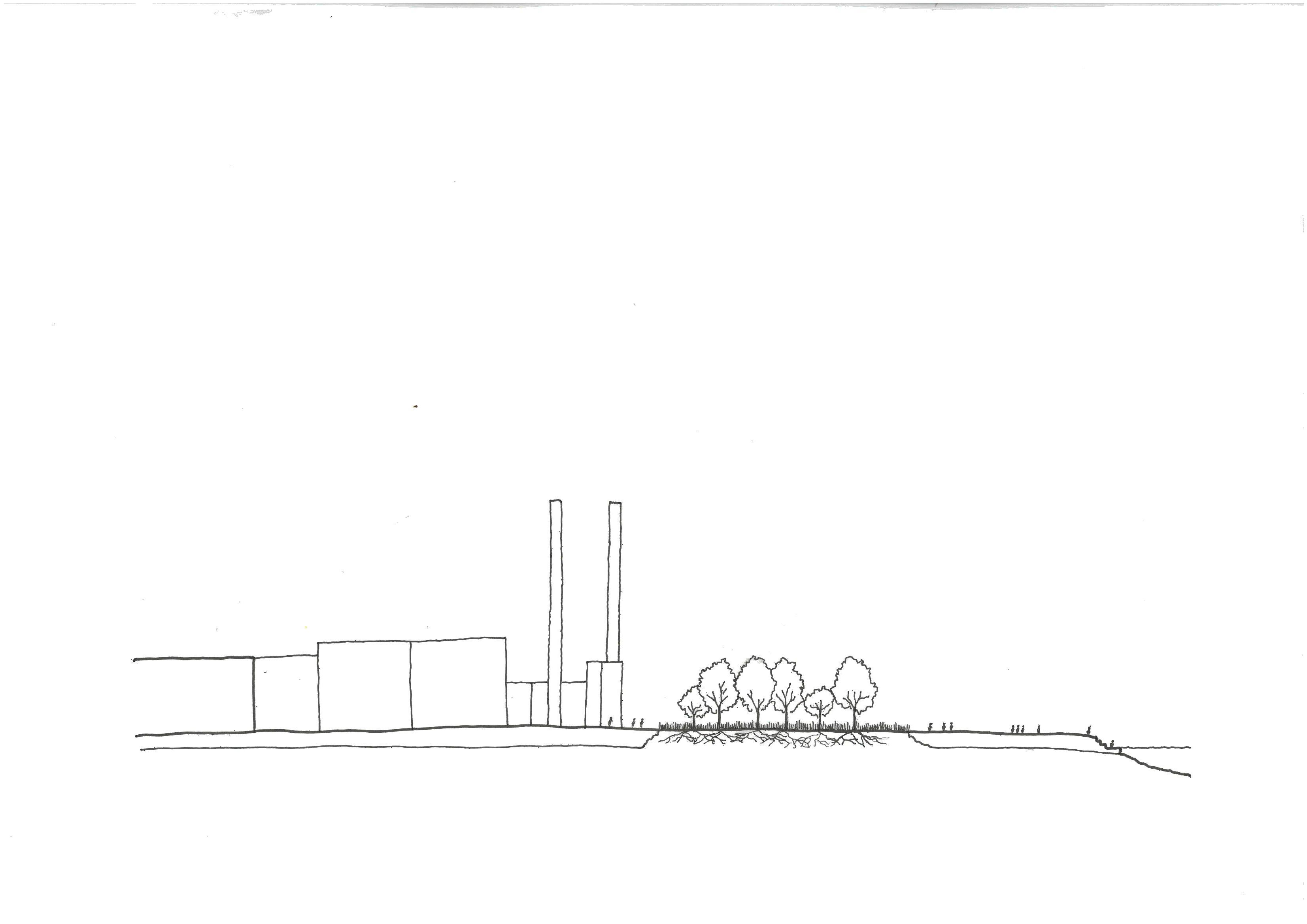

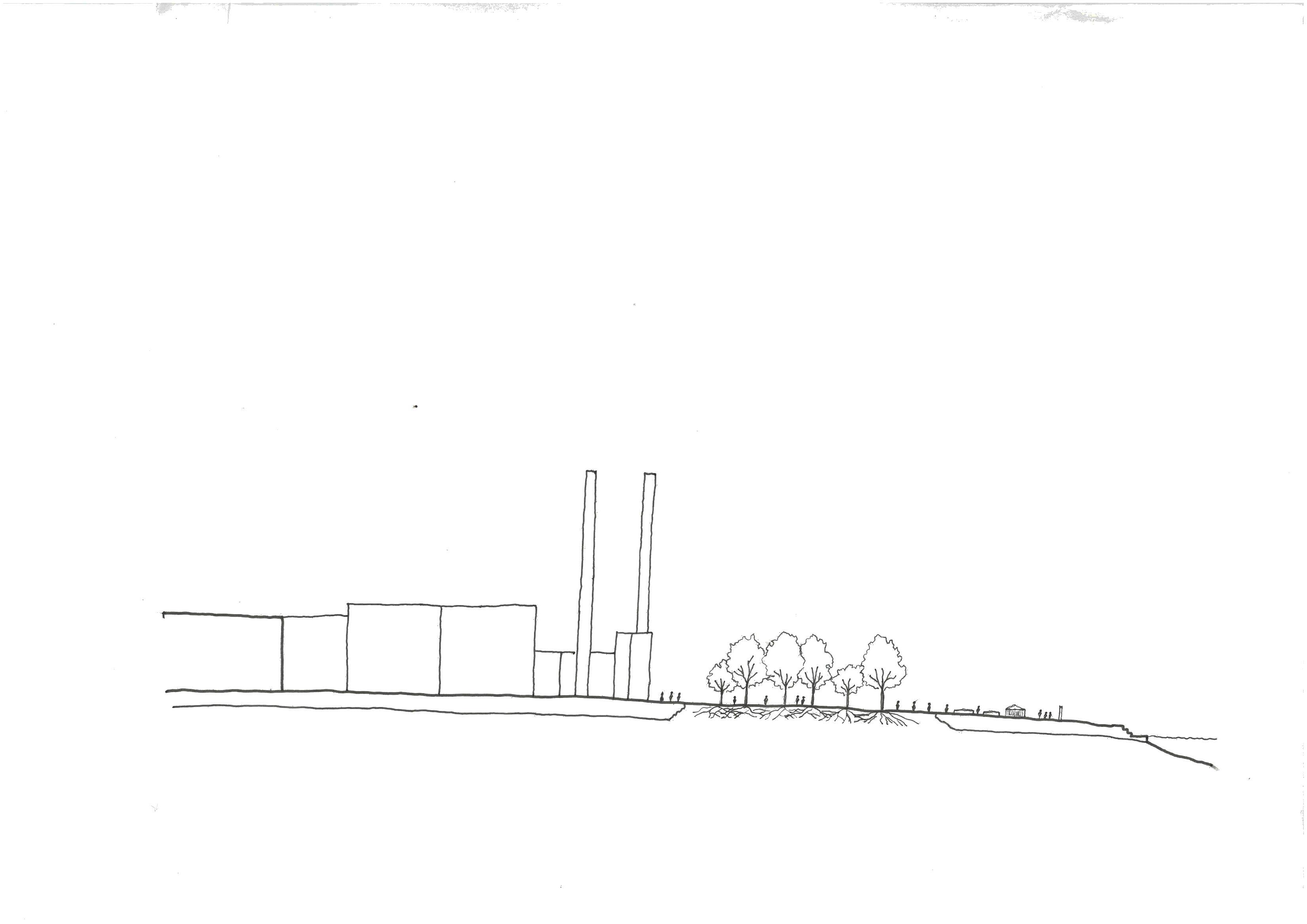

2050 Winter

Phytoremediation is complete, but planting remains to frame public spaces

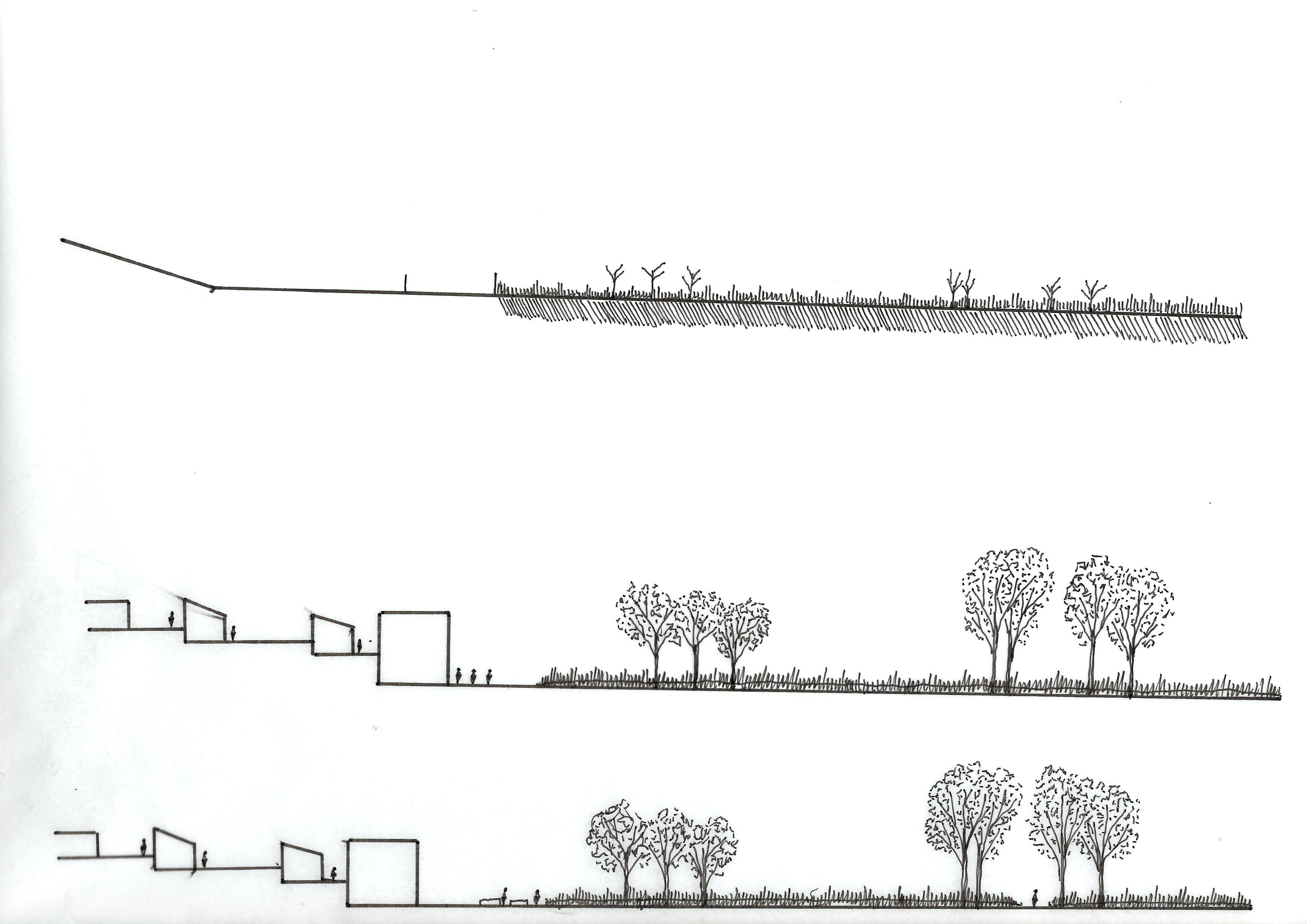

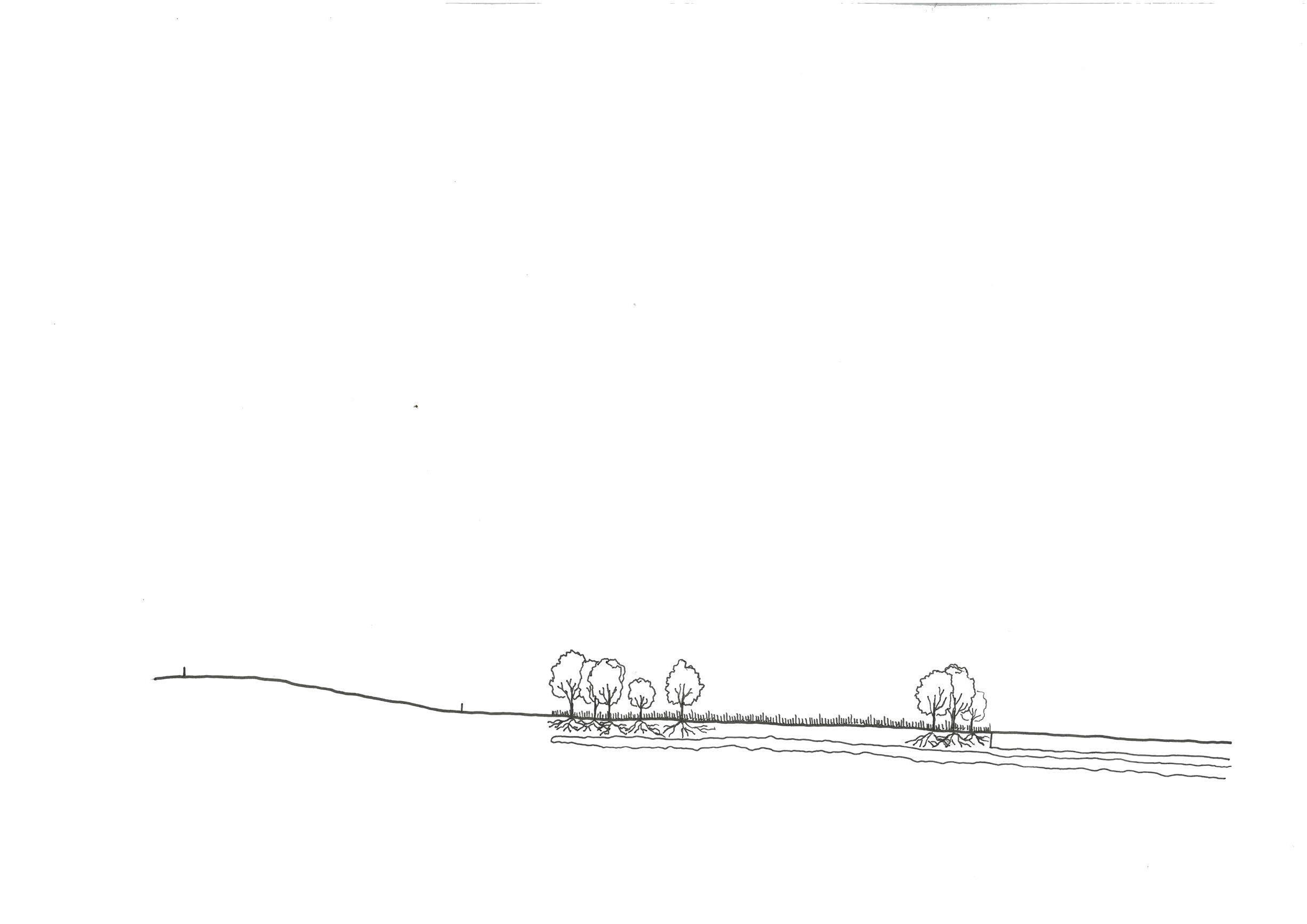

North - South section

2050 Winter

However lead toxins will most likely still remain in the soil

East - West section

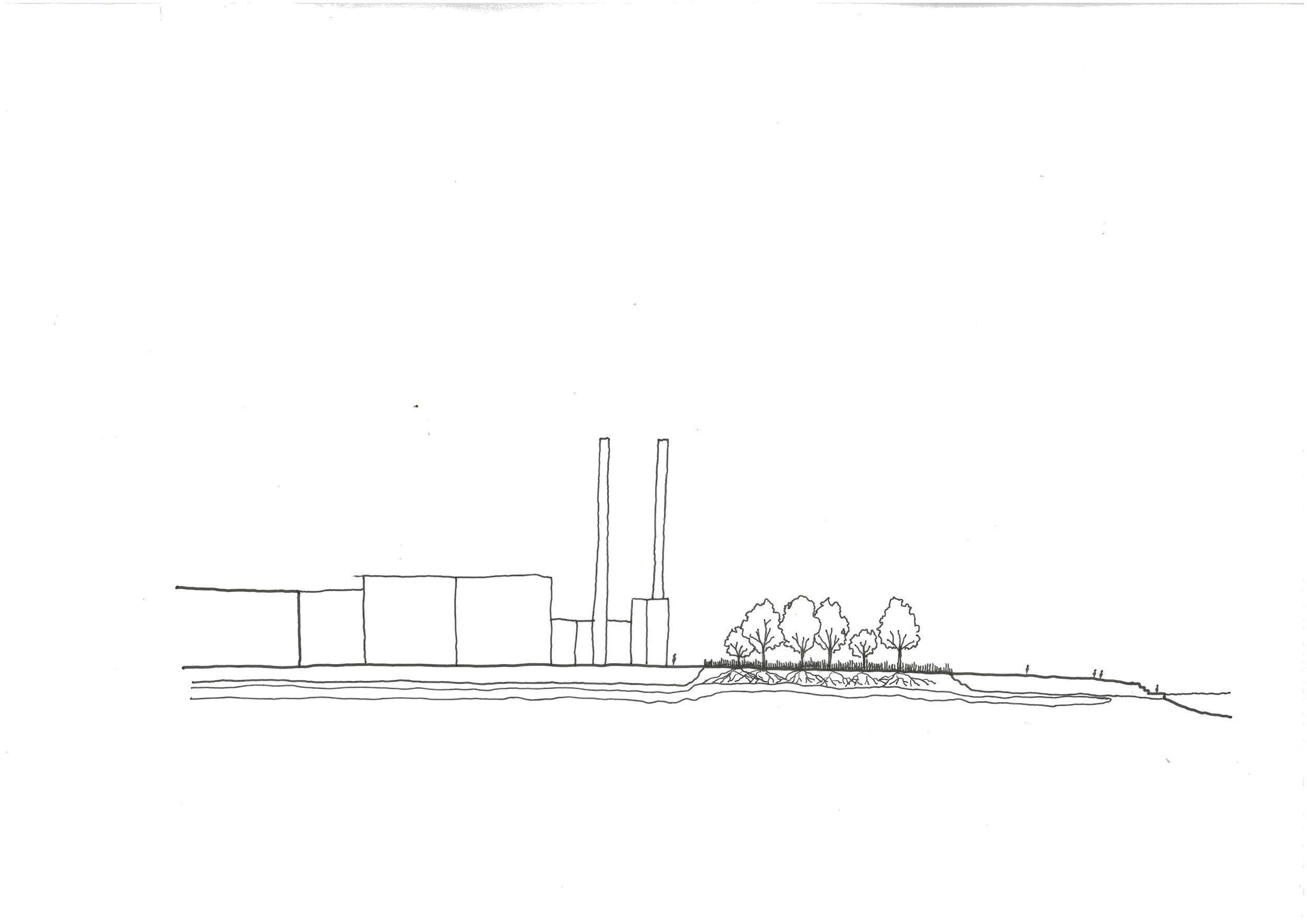

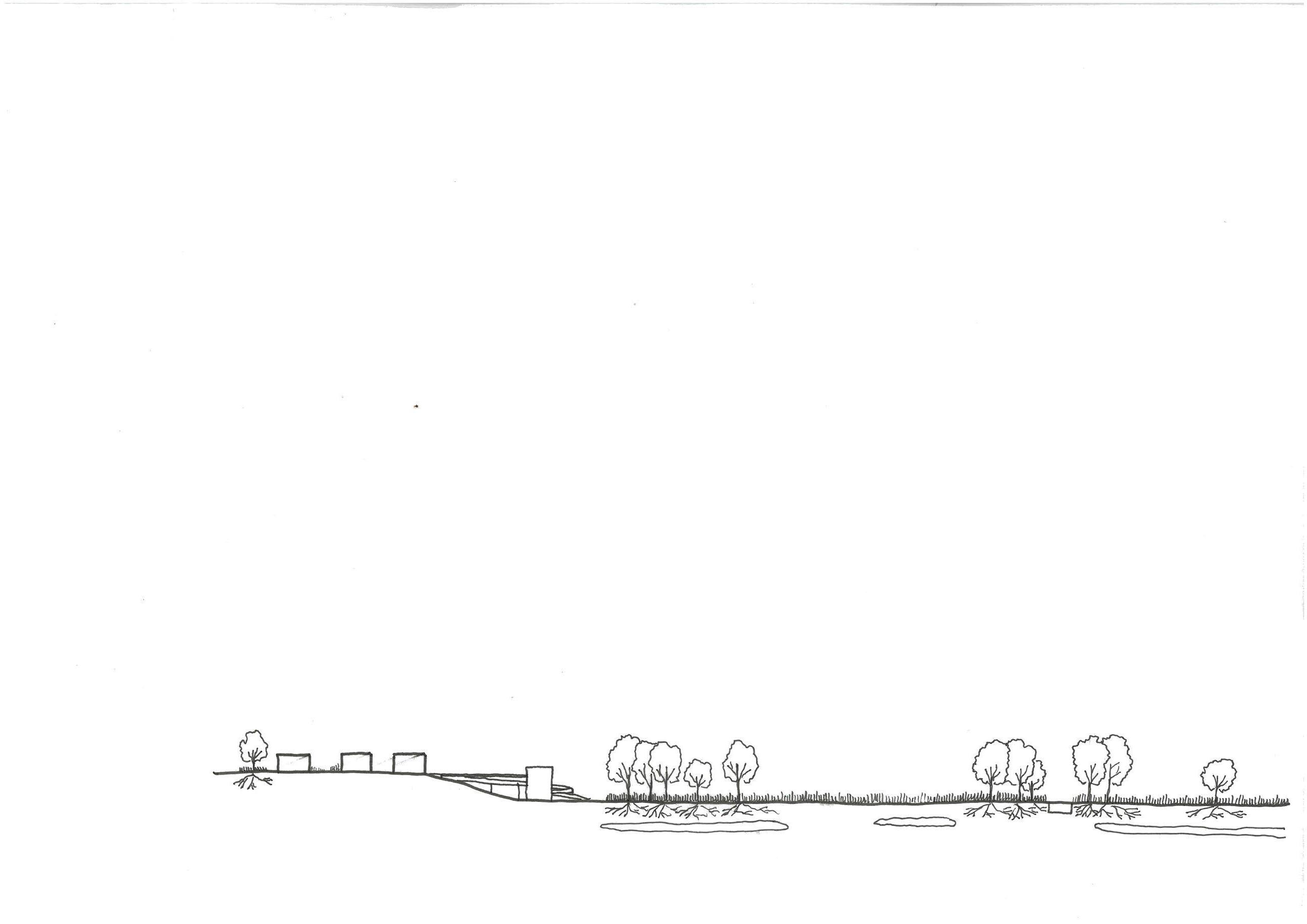

2050 summer

Paths cut through phytoremediation planting allow public space to be opened up during the summer

North - South section

2050 summer

Smaller wandering paths allow visitors access to usually restricted areas

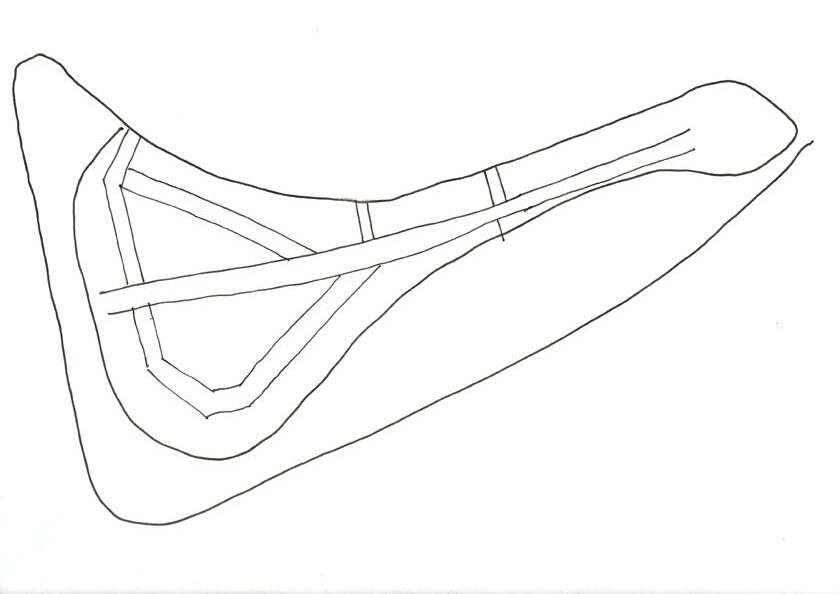

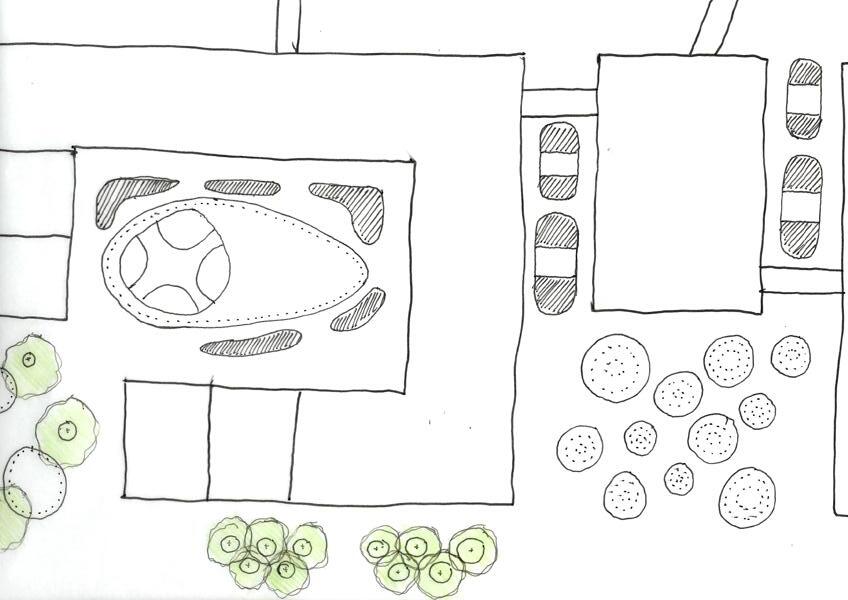

Main streets Streets sketched out

Final iteration

1.