Pre serving with Pur P ose

r eimagining Buildings for Community Benefit

Amy Hetletvedt

© 2025 Amy Claire Hetletvedt

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any means without permission in writing from the publisher: Island Press, 2000 M Street, NW, Suite 480-B, Washington, DC 20036-3319.

Library of Congress Control Number: 2025934649

All Island Press books are printed on environmentally responsible materials.

Keywords: abandoned building, adaptive reuse, architecture, beneficial preservation, blight, building conservation, community participation, disinvestment, endangered building, historic preservation, historic property, incremental development, lowerbudget preservation, poetic intervention, population decline, practical intervention, priority intervention, temporary use, threatened building, vacant property

t his book is dedicated to my beloved father, who, during its writing, left this world for his final and complete restoration.

Chapter 1 Why Buildings Are Being Lost: Burdens and Barriers ............................................

Elimination: The Fallacy of a Clean Slate 14

Exploitation and Exportation 17

Barriers in Historic Preservation Standards and Designation 20

Barriers in Process: Financing and Delivering Professional Services 23

Chapter 2 Why Buildings Matter: Purposes for Preserving .....................................................

Environmental Benefits, Embedded Possibilities 28

Practical Benefits: The Prosaic 31

Narrative Benefits: The Poetic 32 Power of Persistence: Priorities 35 Neighborhood Inventory: Buildings and Values 37 Chapter 3 What Works: Processes and Perspectives.................................................................

A Perspective on Resources 46

Incremental and Iterative Processes 49

Alternatives for Financing and Delivering Professional Services 54

Considering Historic Preservation Standards and Designation 56

Part II Purposeful Approaches to Existing Buildings

Chapter 4 Priorities: Saving Endangered or Threatened Buildings .........................................

Stabilization: Mullanphy Emigrant Home (St. Louis, Missouri, US) 70

Structural Support: Chantry at Kilve (Kilve, Somerset, UK) 77

Mothballing: Homes of Springfield District (Jacksonville, Florida, US) 81

Protest and Documentation: Richard Nickel in Chicago (Chicago, Illinois, US) 86

Moving: Collected Thoughts and Examples 91

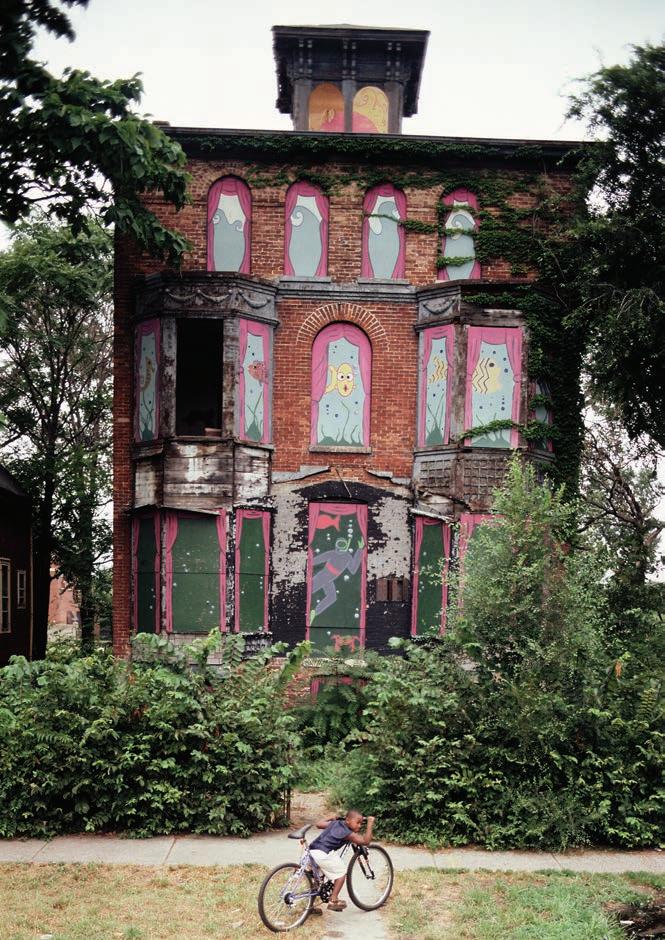

Conversations: The Heidelberg Project (Detroit, Michigan, US) 106

Interlocutors: The Marysburg Project and The Dollhouse (Marysburg, Saskatchewan, 110 and Sinclair, Manitoba, Canada)

Witness for Justice: Ben Roy’s Service Station (Money, Mississippi, US) 117

Witness for Peace: Bombed Out Church (Liverpool, Merseyside, UK) 121

Memory Markers: Collected Thoughts and Examples 125

Shelter: Million Donkey Hotel (Prata Sannita, Italy) 144

Gardens: Plant Concert in the City Club (Newburgh, New York, US) 149

Remediation: De Ceuvel (Amsterdam, The Netherlands) 157

Education: Bánffy Castle (Bonţida, Romania) 162

Individuation: Denny Row Housing (Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, US) 168

Part III Community Examples: Profiles of Purpose

Classic car tail light detail, 2009. (Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, photo by Carol M. Highsmith [LCDIG-highsm-04405])

Preface

“I never considered myself a great architect. I’m more of a creative problem solver with good taste and a soft spot for logistical nightmares.”

—Maria

Semple, Where’d You Go, Bernadette

I thought it was a hearse I was looking at.

We pulled up to the old Redford Theater on Detroit’s West Side. It was the early 2000s—at the end of the thirty years or so that the world had forgotten about Detroit, the decades in which it existed outside of time, in its own orbit, and the gaze of the world was still turned away. There was a force field, an invisible line around its borders, and what went on inside was isolated, a world within itself.

This is not to say that it wasn’t influenced by larger socioeconomic forces, but for those decades, which encapsulated the twenty-year tenure of Mayor Coleman Young, the outside world left Detroit alone.

It was the major criticism I had of my architectural education in nearby Ann Arbor. Not once did I have a studio project that engaged with this urban metropolis 40 miles away. I was assigned design studies like a loft for a violin maker, a bridge in an Olympic village, a rural retreat for an artistic couple,

and although my design abilities progressed through these exercises, I wondered what sort of architects this education was preparing us to be.

As a provocative project for a class in my third year at university, I created an installation that hung on the wall outside the administration corridor of the architecture school. I am home(less) un(less) was a series of black boards with stark white text. Each board was hinged and opened with a salvaged metal cabinet handle. The handles invited passersby to lift them up and peek into reflective statements about their present, their future, and their relationship with the other. Who exactly were we becoming? Who were our clients? What did our own choices—both in life and in vocation—mean for others and the world around us?

I have no way of measuring this installation’s effect except on myself.

After a stint on the West Coast, completing graduate school and working in the urban context of a thriving tech-boom economy, my husband and I moved to Detroit. We settled into a brick Tudor in an East Side neighborhood during a time in which it was a statistical anomaly for a White person to be moving into Detroit.

Early in those years, we found ourselves on one summer evening pulling up outside the Redford Theater. It was one of the few neighborhood theaters still open in Detroit, the anchor of a one-story brick commercial strip. Operated by the Motor City Theater Organ Society, the Redford still had its working pipe organ, and the live prelude and postlude were the sound spectacles that had drawn us there.

But outside was an even more fantastical prelude. Underneath the hulking cantilever of the marquee, what appeared to me as a hearse was parked in front of the theater, a ’60s machine, long and low, a chariot of luxury and dignity—except that it had been modified to look like the Ectomobile from the 1980s movie Ghostbusters.

It had bullhorns mounted on the hood. A siren on its roof gleamed in the low evening light. And emblazoned across the side of the front door was the slogan “Motor City Blight Busters.”

I loved this vehicle immediately. Its rich symbolism: an automobile as the savior for the Motor City! I loved it for its cheekiness. And I loved it for all the questions that it brought to my mind.

How exactly were they busting blight with this fantastic machine? What did they store in its cavernous back end? Was it equipment to take down? (I envisioned sledgehammers, crowbars, explosives?) Or was it equipment to build up?

Furthermore, what was blight?

Was it a physical condition of deterioration? Or was it socio-psychological, like a collective feeling of hopelessness?

How would this outlandish machine fight hopelessness? When you opened up the rear door, would a bunch of balloons crowd out and lift up to the sky? Maybe a cannon shooting out encouraging messages like backfires from its tailpipe?1

Much was crowded into our decade in the city after we encountered the Blight Mobile. I grew and learned from the experience of living in a community where I was a racial minority. We joined the neighborhood association, which cooperatively funded, for example, the snow plowing of side streets that the city did not provide. We ran up against challenges that were common to all residents of the city at that time, daily frustrations and inconveniences of living in a place where systems were breaking down or broken. The public lighting system was a disaster, the city was pronounced a food desert,2 and the emergency network was stretched to its limit.

I learned professional lessons from practicing architecture in Detroit and in my time serving on the city’s Historic District Commission. I participated in difficult decisions, meeting with countless situations where an owner’s means could not keep pace with a building’s needs and others where an owner saw their historic building not as an asset but as a nuisance or obstacle.

As metal theft continued to rise aggressively,3 our state-based preservation network advocated for stronger scrap yard monitoring and accountability. Many church clients had their flashings and gutters stolen. Flashings and downspouts are necessary, but continuous replacement was demoralizing. They’d rather have spent their money on other things. (As I would have when my car’s catalytic converter was sawn off in a church parking lot.)

The ten years that we lived in Detroit were the longest I’ve lived anywhere. And in the ten plus years since then I’ve continued pursuing the questions I began asking there about buildings, about blight—about disinvestment, demolition, and the metaphysical chasm between ruin and restoration.

The ideas in this book are built on my own experiences and those of many others. In my personal and professional journey, I’ve learned from the work and writings of community activists such as Dr. John Perkins, architects such as Samuel Mockbee, and artists such as Sister Corita Kent. I’m inspired by neighbors and friends in Detroit and people I’ve met who are living and working in disinvested contexts and caring for buildings all over the world.

Although my own life has been itinerant, I admire the character and persistence of those who have remained firmly rooted in place and community.

Great Architecture with a capital “A” has never been, for me, the primary interest or the end goal. Logistical nightmares need champions. Problems need thinkers and riskers. Complexity invites us further in. Entering into complexity demands something of our intellect and imagination as we begin to unravel causality and envision solutions. But it demands something of our hearts as well: conviction and compassion.

During the writing of this book, I sat down with John George, founder of Detroit Blight Busters, on a snowy morning in the busy café started by Blight Busters on Detroit’s Northwest Side.

Of course, I asked about the Blight Mobile. “So, what kind of car was that thing? Was it a hearse?”

“Naw. It wasn’t a hearse. It was a turquoise station wagon that had been used as an ambulance.”4

Funny, a vehicle that for the last twenty years in my mind has been a conveyance for the dead was actually an ambulance to assist the living. This revelation was a clarion call for me: So-called blight is best addressed not with a hearse but with healing.

Whether you’re an architect who has been invited to work in a disinvested community, a resident, activist, or artist engaging with existing buildings, or someone who is simply drawn to think more deeply about the why of vacant, abandoned, and distressed buildings and what we can do about it, I invite you in. I invite you to enter into this conversation with your whole person.

In the topsy-turvy world of Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, created by Lewis Carroll, Alice asks the enigmatic Cheshire Cat, “Would you tell me, please, which way I ought to go from here?” He replies, “That depends a good deal on where you want to get to.”5 This book is not a recipe or a roadmap but an open discussion on how, together, we can incrementally change course.

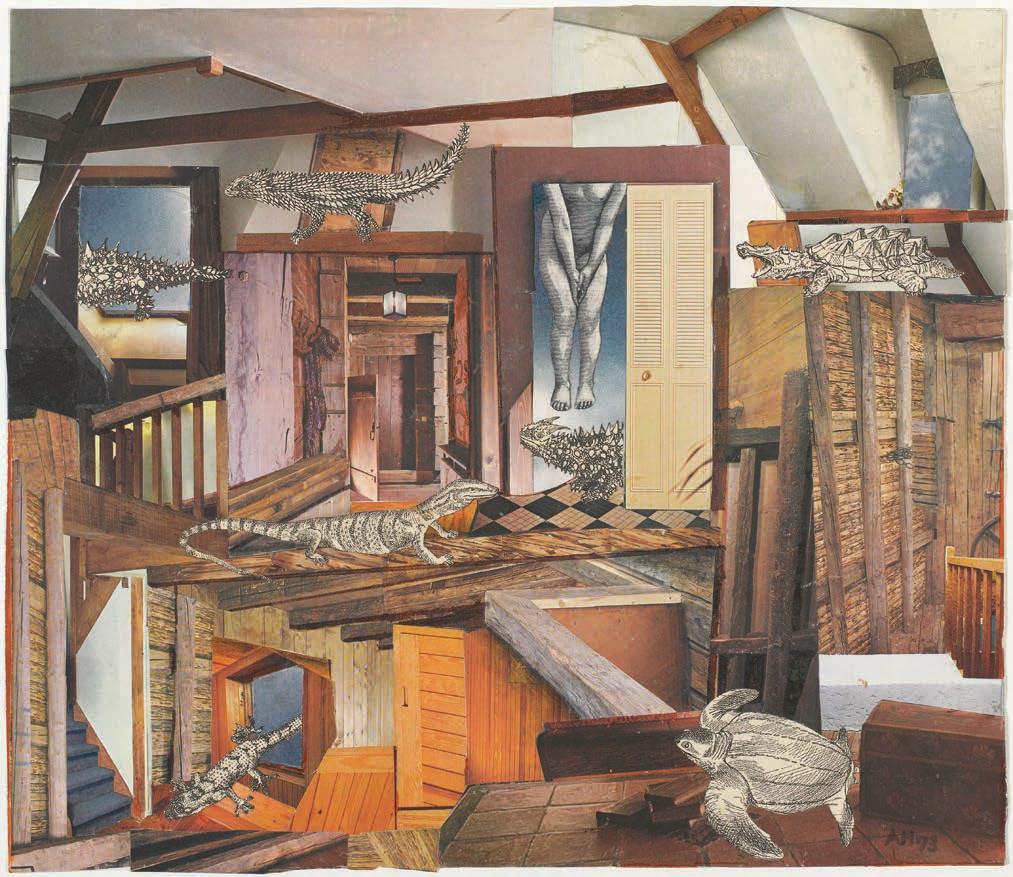

In this collage, reptiles inhabit the spaces that humans have left behind while the figure outside the door kneels to peek in. Do we, together as humans, dare be invited back into the process of creation within the wreckage we’ve made of Eden? (Guests in an Abandoned House, circa twentieth century CE. Collage, paper. 34.6 × 39.9 cm. inv no. AM1981-160. Photo by Audrey Laurans. Artist: Adolf Hoffmeister [1902–1973], Czech painter. Location: Centre Georges Pompidou/Paris/France. Digital Image © CNAC/MNAM, Dist. RMN-Grand Palais/Art Resource, New York, NY)

Introduction

“Years of experience, much of it forged in the crucible of misguided programs such as urban renewal, have clearly demonstrated the folly of destroying a place in order to save it.”

—Richard Moe, Rebuilding Community

One of the most sustainable things we can do at a societal scale is to invest in existing communities, making use of the embodied energy of generations before us. Yet investment flows into developing greenfields further and further from our historic city centers and in thick blankets around rural towns, leaving core communities more vulnerable and underresourced.

A slow drive down Lafayette Avenue on the South Side of Chicago in 2019 reveals a streetscape not so different from other disinvested Rust Belt communities, with empty lots and abandoned or distressed buildings. Some of the remaining buildings are neatly kept, trying to hold it together. Vacancy characterizes much of the neighborhood.

The density of this neighborhood in 2019 is perhaps not so different from what it was in 1870, when John Raber chose it for building a brick Italianate residence on 6 acres. Now, the landmarked Raber residence is almost com-

The Raber House in Chicago in 1999.

(Photo by Camilo José Vergara.

Raber House, 5670 S. Lafayette Ave., Chicago, 1999. Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division [reproduction number LC-DIGvrg-09604])

pletely obscured by tree growth and vines, its boarded windows rendering its tall façade expressionless. Further down the block, a twentieth-century brick building, formerly the home of the Mount Mariah Missionary Baptist Church and Deliverance Healing Temple, is also vacant, its windows filled with wavy glass blocks. On the half-dozen lots between them, the only structure that remains is a single-story bungalow from the 1960s, its picture window embellished with white shutters and a single trimmed shrub. Around this home, a chain-link fence defines its island.

“After generations of municipal neglect, predatory lending practices, and increased waves of foreclosure, the neighborhood was hollowed out and its structures demolished,” Sweet Water Foundation details.1

“Compounded by several decades of loss of population . . . the area sat vacant, ‘blighted,’ and deeply scarred” by what Sweet Water Foundation describes as a “constructed ecology of absence,” explains Anthony Balas in a Mellon Foundation publication of their interview.2

This constructed ecology includes the built environment, part of our whole Earth ecosystem. In disinvested communities, the deep effects of absence are visible within the constructed ecology. There is a marked vacancy and lack of investment to fully address the properties that remain.

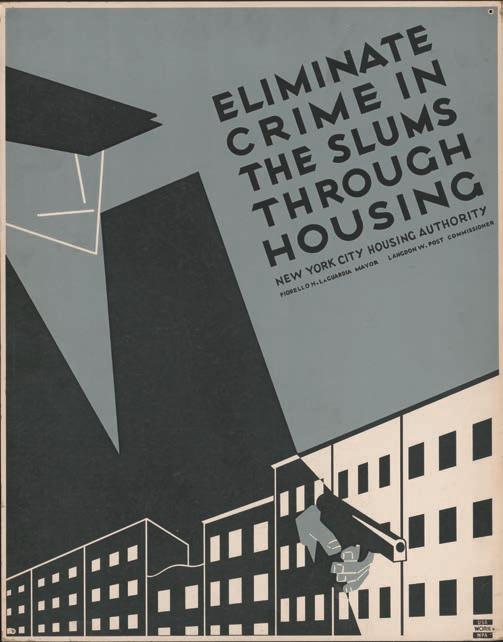

Much of the direct demolition of the built fabric in urban communities in the United States took place through federal programs: so-called slum clearings beginning in the 1930s and urban renewal and transportation planning projects of the 1950s and 1960s. Many urban freeway construction projects during these decades reinforced inequalities by destroying or isolating lowerincome neighborhoods while providing a convenient conduit for those with the means and opportunity to work in the city but live in the suburbs.3 Essentially, these large-scale transportation projects aided in draining the cities. Generational wealth, economic stability, and deep sociocultural connections were affected, and the effects continue to be felt in these communities today.

The preservation movement in the United States gained traction in the 1960s, sparked by the demolition of Pennsylvania Station in New York City in 1963. Yet as Richard Moe, former president of the National Trust for Historic Preservation, points out, the nascent decades of the preservation movement in the United States were also the tail end of decades in which bulldozers had been blazing through inner-city communities in the name of urban renewal.

“Abandoned buildings can break a neighborhood’s heart,” Moe says. “Demolished buildings can destroy its soul. When disinvestment, poor maintenance and abandonment leave a neighborhood pock marked with vacant or dilapidated buildings, public officials and citizens often seek a quick solution to the community’s woes by razing the deteriorated structures. Demolition may effect a dramatic change in the neighborhood’s appearance, but it’s rarely a change for the better.”4

A Works Progress Administration–era poster promoting new housing as a crime deterrent, 1936. (Eliminate Crime in the Slums Through Housing. New York, 1936. Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division. New York: Federal Art Project. [LC-DIGppmsca-52154])

A sales office for new houses on the outskirts of Detroit, Michigan, 1941. (Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, FSA/OWI Collection [LC-USF34-063667-D].

Photo by John Vachon)

The aesthetic of abandonment deeply affects its residents. Planner Alan Mallach describes how the disinvested environment can reflect a pervasive lack of hope that has deep sociological roots.5 Abandoned buildings can be a source of physical danger, from unstable building elements to hazardous materials to a harbor for criminal activity. In many ways, abandoned, distressed, and underused buildings are experienced as burdens.

But removing these buildings can also have negative effects. University of Toronto professor of geography and planning Jason Hackworth states that “research affirms some of the concerns being raised by scholars and local officials about past uses of demolition as a stand-alone device, namely, that absent some other form of affirmative development, disinvested neighborhoods do not autonomously revive.”6

Healthy communities need buildings. In disinvested communities, vacant, abandoned, or deteriorated properties (or VAD properties, as referred to by the Center for Community Progress7) are often viewed or experienced as burdens. Yet they also can be reintegrated into an ecosystem of use and serve as reminders of the diverse experiences that have shaped our society.

Disinvested communities, as I define them in this book, are areas that are experiencing or have experienced limited investment and economic activity and are characterized by low property values. The effects of disinvestment include a high incidence of VAD properties. A community can remain in what the Center for Community Progress calls a cycle of systemic vacancy for years, even decades.8

In this book I explore how artists, activists, and architects are creatively redeveloping buildings in ways that can be strategic for disinvested communities. Some of these redevelopments offer practical benefits to the community, providing shelter, space for artistic endeavors and creative enterprises, opportunities for teaching and learning, and places for growing food and gathering. Other creative approaches may have a role that is not practical but more poetic or prophetic.

Working in the South Side Chicago neighborhood of the Raber House and Deliverance Healing Temple during its multigenerational harrowingout (in the words of the Sweet Water Foundation from their interview with Anthony Balas), the Sweet Water Foundation gathered and shared life experiences with neighbors.9 Soon after acquiring the abandoned church building in 2019, they received a grant from the National Trust to reimagine and revitalize spaces in the community.10 The foundation proposed focusing commu-

nity efforts on the church building, renamed the Civic Arts Church, instead of on the Raber House.

The Raber House, which was landmarked by the City of Chicago in 1996, had not found an investor or a new use. The Sweet Water Foundation saw that the nearby abandoned church held different stories and different possibilities for regeneration. Although the church was not landmarked, it was seen as having greater potential to benefit the community as a hub of activity around the arts and its importance in telling certain stories. “The act of preserving and transforming the church . . . will unveil elements of Black History in Chicago that are untold and will reactivate a community asset that is deeply rooted in the history of the people who live in the neighborhood today,”11 reads a Sweet Water Foundation publication about the project.

As this example demonstrates, although prominent historic buildings can have importance to a community, sometimes buildings that are considered nonhistoric can have equal or greater importance. And, as architect Beth Brant points out in an article for AIA Dallas, reusing so-called nonspecial buildings can have greater sustainability impact than reusing the so-called special ones.12 Buildings from a broad spectrum of time can be creatively reused to serve purposes that benefit the community.

In Preserving with Purpose, I argue for saving buildings that are of value to the community. Whether the building becomes a symbol of resistance, a place of refuge, a teacher, a business incubator, or whether interventions at the site help clean the soil or serve as a marker for mourning or remembrance, good can come to the community through even temporary or partial reuse of an underused site. I believe that widespread demolition removes certain possibilities of goodness without preventing gentrification.

When I talk with people about approaches to the reuse of buildings in disinvested communities, the question that arises most frequently is, “Doesn’t this lead to gentrification?”

My response is, “Sometimes.” The negative effects of increased investment and raised property values, such as displacement, can occur. Offering discussion in several community profiles about inclusion or affordability as community priorities, I advocate for retaining and building on the physical resources within disinvested communities because, as Alan Mallach points out in his book The Divided City, “the reality is that today most neighborhoods that don’t revive, go downhill.”13

In this book, I suggest ways that professionals such as historians, architects, and urban planners who potentially come from outside a disinvested community can participate in a way that respects and empowers community members to consider the best method and use of existing buildings. Part II of this book features examples from around the world of buildings that have been prioritized and strategically preserved by their community for later redevelopment and buildings that have been repurposed or adapted for practical or poetic purposes. This catalog of approaches developed in part because it was a resource that I wished I had in discussions with clients—something to spark the creative process.

Part III offers profiles of four places that were in a cycle of systemic vacancy or at a stage of critical abandonment but have, over time, redeveloped buildings by using the approaches described in this book. Three of these profiles—Project Row Houses in Houston, Texas; The Dorchester Projects and Stony Island Arts Bank in Chicago, Illinois; and Menokin in Warsaw, Virginia—are in the United States. The fourth profile, of 10 Houses on Cairns and the Granby Winter Garden, is in Liverpool, England. Menokin is in a rural area and the others are urban. The examples all have different stories, of course—different ownership models and different dynamics that have played

A Juneteenth celebration at Civic Arts Church in 2024. The new sliding door on the side of the building activates the open space between the church and the adjacent residential structures, including the Raber House. (Courtesy of Sweet Water Foundation)

out over time between the individuals and groups involved. Yet in these communities, artists, residents, activists, and architects have approached existing buildings in strategic, creative, purposeful ways.

Although this book is written for a global audience, the perspective is firmly situated in the United States. For example, the book uses the term preservation (an Americanism) rather than the term conservation, which is more commonly used in other places around the world.14 I apply global observations to the architecture and preservation fields in the United States because they are the systems in which I was trained and licensed. And because it’s my home culture, it’s the one with which I am most familiar and feel the most freedom to approach critically.

In addition to discussing the loss of buildings, this book also identifies some barriers to saving them within the disciplines of historic preservation and the building service professions. My goal is not necessarily to revolutionize existing systems but to help make space within them—to create a parenthesis of opportunity—for more buildings in disinvested communities to remain. Architect–preservationist Deborah Burke describes existing buildings as an opportunity “for cities to engage with historical trauma, encourage cultural continuity, and move beyond generic expectations of what older structures can become in a rapidly changing world.”15

Five years on from a pandemic that underscored our interconnectedness and fragility, we somehow find ourselves more splintered and divided than ever before. We’re haunted by persistent social inequities and the urgent ticking of the environmental clock. But when we pause to look around us, we can see afresh the good work that is happening and has already been happening for years, good work that is often overshadowed by higher-budget projects and the insatiable cycle of consumption.

We are no longer in an age (if indeed we ever were) where the Howard Roark archetype of the solitary professional can succeed in addressing the complex issues of our society.16 We must engage with others not only about how we got to this point but how, together, we can move forward. We can change course away from this constructed ecology of absence and the churning consumption of greenspace toward purposefully preserving environments with existing buildings that are fertile with hope for individual communities and for our planet.

Chapter 1

Why Buildings Are Being Lost: Burdens and Barriers

“What I was going to do would technically be stealing, but from whom? A memory? The people who had abandoned it? The governments that allowed it to fester?”

—Drew Philp, A $500 House in Detroit: Rebuilding an Abandoned Home and an American City

The scale of Detroit’s depopulation is vast. In the postwar production boom of the 1950s, Detroit reached its peak population of 1.85 million. By 2020, seventy years later, the population had fallen to 640,000, or just slightly over one third its former size.1 Dispersed over a landmass roughly equivalent in size to Manhattan, San Francisco, and Boston combined, Detroit’s remaining population contended with an outsized infrastructure2 and a slow unraveling of the built environment its resources no longer supported. Disinvested communities like Detroit are staggering under the economic and psychological burden of vacant, abandoned, and distressed properties. These buildings, their disappearance, and the disinvestment surrounding

them are not just inherited problems or a random collision of unfortunate circumstances but the result of socioeconomic forces and deliberate choices.3

A policy brief produced for the Vacant Properties Research Network states, “Even though many of the forces and factors responsible for blighted properties are difficult to see, this invisibility does not mean that blighted properties are natural results of urban and suburban development. On the contrary, a number of federal, state, and municipal policies and market trends have helped to create blighted conditions in the U.S. . . . The emergence of blighted properties in shrinking and deindustrializing cities in the U.S. is not happenstance. The emergence of blighted properties is part of a larger pattern of deterioration and neglect.”4

Disinvestment has a cause, and it also has a cost. In the early 2000s, depopulating Rust Belt cities such as Buffalo, New York, and St. Louis, Missouri, counted more than 30,000 vacant housing units each. The count in Cleveland, Ohio, was 50,000.5 A 2022 report by the Center for Community Progress states that a conservative estimate of the minimum cost to address vacant and blighted structures in the state of Michigan alone is $1.7 billion. “The direct costs to address these properties,” the reports states, “are more than individual communities can bear.”6

And the costs are more than economic. In his article “How Detroit Became the World Capital of Staring at Abandoned Old Buildings,” journalist Mark Binelli recounts Detroiter Marsha Cusic speaking of the “retinal scars” that Detroit’s ruined buildings left on children living in the city.7 Her metaphor left a lasting impression on me. The longer I lived in Detroit, the more I understood how the residual outline of each distressed building was seared into the community’s consciousness.

By communities or by owners with more capital resources, historic buildings are being saved. They’re being rehabilitated, restored, reused, reinterpreted. Dovecote Studio in Suffolk, England, a steel structure inserted into a partially ruined stone building, is the darling of creative ruins activists. At Bunny Lane House in central New Jersey (United States) architect Adam Kalkin enclosed a nineteenth-century clapboard house inside an industrial steel shed. In Maastrict, the Netherlands, a bookstore situated inside a historic Dominican church is a pretty good approximation—to my mind—of paradise on Earth.

Artist Rachel Whiteread cast a concrete sculpture of a Victorian terraced house and placed it on an empty block that had once been lined with such homes for working-class Londoners. It served as a collective memory device, a heavy ghost of the block’s built past. (Rachel Whiteread; House, 1993; 193 Grove Road, London E3. Destroyed 1993. © Rachel Whiteread; Photo by Sue Omerod. Courtesy the artist and Gagosian)

Photographer Richard Nickel documented metal scavengers leaving the former Chicago residence of architect–engineer Dankmar Adler, which was demolished three days later. (Dankmar Adler Residence, Adler and Sullivan, architects. Photo 1961. Richard Nickel Archive, Ryerson and Burnham Art and Architecture Archives, The Art Institute of Chicago. Digital File # 201006_110815-061)

And yet, in disinvested communities, historic buildings—resplendent with just as many lovely, creative opportunities—are being lost, continuing the cycle of disinvestment. This chapter explores some of the reasons why, to build a foundation for understanding how community residents and professionals can find a different way forward.

Elimination: The Fallacy of a Clean Slate

When populations recede, what’s left is an outsized infrastructure. Population reduction leaves a plentiful supply of buildings but no demand. Property values plummet. Access to capital and other resources dries up in inverse proportion to outward flow, like the slow and squeaky turning off of a tap.8 The Center for Community Progress explains sustained or increasing vacancy (or “systemic vacancy”) as a looped cycle. A once-vibrant neighborhood faces equity challenges (such as discriminatory or predatory lending), external triggers (such as a natural disaster or an economic crisis), a market shift (demand decreases), and then increased vacancy. The impacts of increased vacancy can fuel further challenges and perpetuate the cycle.9

When communities experience disinvestment, buildings can suffer what is called demolition by neglect, which is the gradual and terminal deterioration of a structure due to lack of maintenance. For example, if a roof leak is unrepaired, water eventually weakens and destroys the structure. Sometimes demolition by neglect occurs when, despite good intentions, owners lack the funds or technical resources to maintain the structure. When real estate prices bottom out, owners who do have access to funds often choose not to invest in maintaining a building because of the diminished property values and what is perceived as a negative rate of return.

When large numbers of buildings experience demolition by neglect, distress, abandonment, and vacancy, a community’s aesthetic becomes a constant visual reminder of brokenness. Consequently, the vacant and distressed properties can acquire misplaced or disproportionate blame for holding back the community from progress. Overwhelming infrastructure needs, and their cascading drain on physical and emotional resources, can lead to a call for removal.

Demolition campaigns to remove the so-called blighted structures are often welcomed, even called for, by neighborhood residents. Vacant and abandoned structures pose risks to their neighbors that can harm health,

Unattended property: a frozen waterfall from a burst pipe flows out of a vacant house in Detroit that was in otherwise good condition, 2006. (Amy Hetletvedt)

Is demolition the best solution? An exalted excavator above an open field in rural Michigan, 2024. (Amy Hetletvedt)

emotional wellbeing, and municipal revenue.10 These effects can compound conditions in the neighborhood and perpetuate the cycle of vacancy. Overwhelmed by the magnitude of vacant, abandoned, and distressed structures, residents may see demolition as the best option.

In Detroit, a Blight Removal Task Force was convened in 2014 to assess the city’s building stock. The task force identified over 40,000 blighted structures, plus 38,000 structures with strong indicators to become blighted. In total, 78,000 structures or nearly 30 percent of all existing structures in the city were identified as blighted and needing intervention.11 More than 15,000 homes were eventually demolished, with the final house under the federal demolition funds coming down in August 2020.12 “The pace of the demolition program,” according to a publication by think tank Detroit Future City, “earned the City the recognition of running the largest demolition program in the country.”13

In the years after the work of the Blight Removal Task Force in Detroit, a majority of Detroiters held favorable views on the city’s blight elimination efforts.14 Many of the problem properties were gone. Indeed, many community safety problems—such as the potential for an unsecured cornice to fall on a pedestrian or the potential for an abandoned building to harbor criminal activity—disappear with the demolition of the distressed buildings.

Yet where the built and natural environments are concerned, a clean slate is a fallacy. Building materials and demolition debris go somewhere, usually to a landfill.15 The presence of distressed and abandoned structures has been linked to public health problems,16 but so have their demolition and removal. One study associated demolitions with elevated blood lead levels in Detroit children from 2014 to 2017.17 Studies are ongoing.

In view of community and public health issues related to the built environment, it is interesting that the word blight—often used for communities with high rates of vacancy and abandonment—originates from a term for a diseased plant. The Center for Community Progress explains, “Consider the etymology of blight and where it places the blame. The term blight was first used in the sixteenth century to describe botanical disease that led to spreading lesions that decimated crops—something seen as an act of nature, difficult to predict or prevent. So, when applied to properties, the subtext is clear: Blight is random and blameless. But the systemic vacancy that leads to abandoned and deteriorated buildings is anything but random. It is the con-

sequence of a legacy of intentional disinvestment, poverty, unjust policies, and racist systems.”18

But if disinvestment is a cause of blight, is demolition really its cure? Or is it a permanent solution to something that could have been addressed differently—like an unnecessary or premature amputation?

Not all buildings can be saved, and communities do need to change over time. But our society demonstrates, at many levels, a knee-jerk tendency to erase and delete rather than to edit. Indiscriminate, hasty, or broad-scale demolition permanently removes resources that have potential benefit.19

Exploitation and Exportation

In the late eighteenth century, the aesthetic ideal of the Picturesque—that historical artifacts are endowed with an unintentional and inherent beauty— gained momentum through the writings of William Gilpin, Edmund Burke, Denis Diderot, and others. Estate gardens of wealthy landowners began to sprout follies, decayed classical buildings that were constructed in a ruinous state because the ruins were considered beautiful.

It was pure stage setting, an emphasis on experience designed to provoke an emotional reaction to perceived sublimity. Decay became a foil for the abundance of the wealthy and the sense of control enabled by their wealth. It was a fetish of the “haves.” And so it’s worth considering that the perception of beauty in decay depends heavily on one’s vantage point and that economic status has something to do with it.

Architect Sidney Robinson writes of the Picturesque movement, “Not having the money or the time to correct the depredations of gravity, water, growth and decay is one thing. To cultivate them is another.” He concludes this exploration by noting, “The ideals of novelty, surprise, and relaxation depend on intermittency. Repetition renders them dull and inert.”20 In other words, decay can be picturesque if it is a condition from which one has an escape. This dichotomy in the perception of ruins isn’t just a relic of yesteryear. In 2016, artist Ryan Mendoza partially deconstructed a house in Detroit and exported it to an art exhibit in Rotterdam and later to a permanent collection in Antwerp. Removing portions of the structure, which he called “The White House,” left behind the gaping skeletal remains of the donor house on Detroit’s West Side.

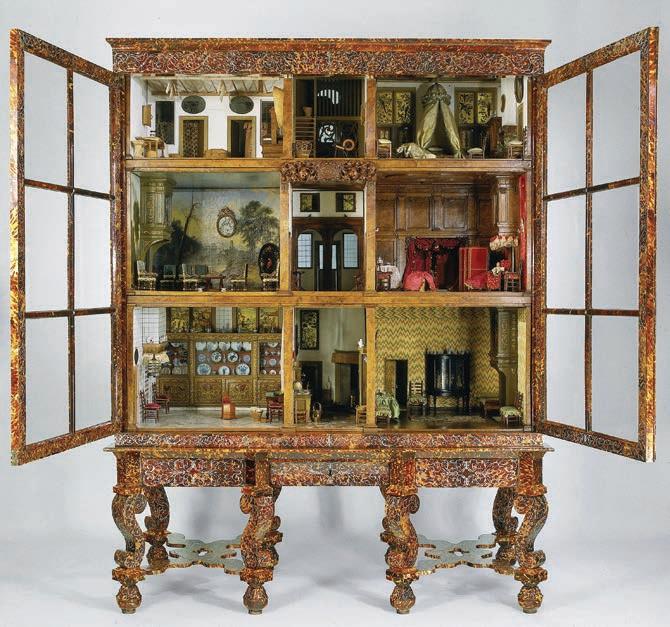

The late-seventeenth- and earlyeighteenth-century upper class exhibited a fascination with elaborate miniatures and curiosity cabinets. (The doll house of Petronella Oortman, anonymous, c. 1686–c. 1710. Public domain. In the collection of the Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam, https://id.rijksmuseum. nl/2002678)

Although Mendoza discussed it as a form of connection,21 others perceived it differently. “I feel disrespected to the max,” said neighbor Beverly Wuong in a Detroit Free Press interview.22

This outrage and sense of disrespect is like that fueled by ruins porn, a term that denotes the photographic exploitation of ruinous structures. Architecture writer and critic Catherine Slessor explains that ruins porn “shamefully overlooks and overwrites the voices of those who still call the city home. Through its reductivist and disassociative prism, endemic social injustices such as poverty, marginalization and racism are ignored or ridiculed.”23

Brian Farkas, a Detroit Building Authority project manager, said of Mendoza’s White House project, “You can’t do this in Detroit anymore. This is not everyone’s canvas. These are neighborhoods. People live here.”24 In later chapters, I explore the idea of neighborhood as canvas and the ways in which large-scale artistic endeavors can have potential benefit.

Exportation and exploitation of vacant buildings, though quantitatively much smaller in scope than removal by demolition, have an outsize psychological impact on community residents. Exportation and removal are rife with ethical questions about intent, belonging, and protection. Drew Philp, author (and owner) of A $500 House in Detroit, recounts a conversation with his friend Nate about whether he should salvage the front door from the abandoned house across the street for use in his own house.

“Ahh, it’s fine. It’s going to go to waste if you don’t. They’re going to tear that house down. Or it’ll be taken by someone else. You’re really protecting it,” Nate said earnestly. His argument seemed like the same one used to take mummies from the pyramids and justify them sitting

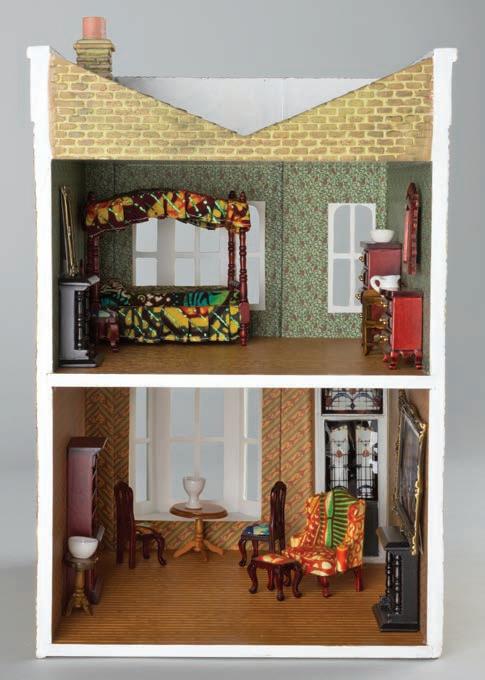

A more recent dollhouse. Here, Shonibare’s dollhouse recreates a Victorian terraced house in miniature, covering some of the furniture with traditional Nigerian fabric. The reduced scale and depiction of house as plaything call the viewer’s attention to the tendency to objectify others. (Yinka Shonibare, Untitled [Dollhouse]; from the 2002 Peter Norton Family Christmas Project, resin, plastic, wood, paper, and fabric. 33.02 × 20 × 26.04 cm. © Yinka Shonibare CBE. All Rights Reserved, DACS/ ARS, NY 2024. University of Michigan Museum of Art, The Dorothy and Herbert Vogel Collection: Fifty Works for Fifty States, a joint initiative of the Trustees of the Dorothy and Herbert Vogel Collection and the National Gallery of Art, with generous support from the National Endowment for the Arts and the Institute for Museum and Library Services, 2008/2.256)

in the British Museum alongside other antiquities removed for “protection” during colonialism. But this wasn’t Egypt, this was Detroit and this wasn’t a pyramid, it was an abandoned house. What I was going to do would technically be stealing, but from whom? A memory? The people who had abandoned it? The governments that allowed it to fester? . I looked around and it didn’t seem as though anyone was on the street, so Nate and I headed over and ripped the door from its hinges.25

Philp’s conversation with his friend touched on many of the contextual issues of material loss. In a sculpture called Urban Extract in the collection of the Detroit Institute of Arts, artist Charles McGee presents a building extract as object. The extract includes the window of a barber shop that McGee frequented for many years.26 The piece is a poignant exploration of the severing effects of demolition and extraction on memory and cultural connections.

The magnitude of disinvestment in communities such as Detroit has caused many to view demolition as the best solution to a burdensome problem or to view so-called blighted communities as a source for further exploitation and extraction. Yet in both cases, removing resources from a community removes potential opportunities to use those resources in creative remaking. What is being lost is not only the buildings themselves but their potential benefit as physical and sociological materials for rebuilding.

Barriers in Historic Preservation Standards and Designation

Although access to capital is an obvious reason that buildings are not rehabilitated in disinvested communities, it is not the only reason. It’s important to consider the barriers that current systems within the built environment may present. Some of these barriers are in the operational norms of the architecture and preservation professions.

In a 2019 article titled “Why Historic Preservation Needs a New Approach,” Patrice Frey, former president of Main Street America, outlines several challenges to the field of historic preservation, among them the languishing and loss of historic buildings in disinvested real estate markets. “Valuable historic resources lie fallow because demand for space is low and the economics of rehabilitation can be extraordinarily challenging,” she says.27

Frey doesn’t blame the absence of investment alone for the loss of buildings in disinvested communities. She turns to preservation standards and

strategies. “Our toolbox,” says Frey, “has not evolved to keep pace. . Our core preservation tools do not serve all kinds of preservation well.”

Frey takes as an example a two-story brick commercial building in an economically struggling small town. Although it is not especially significant as an architectural resource, it is uniquely significant to the community as an eatery and social hub. “To rehab it in a historically ‘correct’ way—that is, through the stringent application [of] the Standards for Rehabilitation— would be extraordinarily challenging in a town where building valuations are low, traditional financing options are scarce, and historic preservation tax credits are not a likely source of financing.”28

The standards for preservation projects in the United States have evolved little from those established and codified in the 1960s and 1970s. The US Secretary of the Interior’s Standards for the Treatment of Historic Properties offer four categories of treatment: preservation, rehabilitation, restoration, and reconstruction. These categories are organized by their level of intervention in the historic property. Preservation is the least invasive; reconstruction is the most invasive.

Within the discipline of historic preservation, the question about how much to intervene in a building—and thus the idea of organizing the standards according to level of intervention—goes back to debates rooted in the nineteenth century.

Frenchman Eugène Emmanuel Viollet-le-Duc was the architect for the restoration of Notre Dame in Paris in the mid-1800s. The building wasn’t in great shape at that time, having suffered decline and significant damage during the French Revolution. Viollet-le-Duc designed the spire with which we are now familiar at Notre Dame, the spire that burned in the April 2019 fire. (After much debate, the spire has been reconstructed to Viollet-le-Duc’s version.29)

The spire wasn’t historically authentic to the Gothic cathedral. It was Viollet-le-Duc’s historicist vision of the spire, the spire he believed should have been there. Viollet-le-Duc viewed restoration as returning the building to a complete state that had perhaps never existed at any particular moment in the past.30

In contrast to Viollet-le-Duc’s passion for revisionist restoration, Englishman John Ruskin, his contemporary, “abhorred restoration of any kind and defended the aesthetic value of ruins.”31 Rather than engage in speculative or even historically defensible restoration, Ruskin emphasized the moral and

“Our toolbox has not evolved to keep pace.”

—Patrice Frey

memorial role of the structures of the past and said, “We have no right to touch them. They are not ours.”32

Viollet-le-Duc’s approach to intervention was very heavy, Ruskin’s was very light. Over time, the lighter approach won over, and later voices in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, such as that of William Morris, argued for the value of leaving changes that had taken place over time.

The interesting dilemma for disinvested communities today is that although older buildings that are considered nonhistoric are opportunities for more experimental and less financially burdensome approaches, designation can give them a helpful visibility to attract funding. Yet, the nature of the designation process and the need to establish of a period of significance reveal a disproportionate focus on conserving buildings as a monument to a particular period of history or as a historic artifact (a precious object) rather than on the role of the building to serve a community’s needs or its potential for storytelling.33

Buildings in disinvested communities may have lost character-defining features of their architecture to vandalism or decay or may have been substantially adapted for different uses over the years. Referring to the criteria for listing on the National Register of Historic Places, former president of the National Trust for Historic Preservation Stephanie Meeks says, “Those are very high standards to meet, and although standards are important, this high bar tends to limit our perspective of history to architectural significance. There is so much more to our story than that.”34 When character-defining features are foregrounded, what other features (physical, cultural, social) recede to the background?35

The good news is that work is being done to refine the municipal and regulatory systems for buildings (historic and other) and to consider how these systems could be adapted in the context of disinvested communities. Flexible and multilayered approaches are needed to support revitalization efforts in disinvested communities.36

In 2023, the National Conference of State Historic Preservation Officers (NCSHPO) committee released a report on the National Register for Historic Places that advocated, among other recommendations, to “consider adding new criterion for recognition of places of cultural significance that may not retain integrity as traditionally understood, but that may hold deep importance and meaning to groups and communities.”37

In March 2023, the NCSHPO formed a working group to provide recommendations on the standards and their application. American Institute of Architects Historic Resources Committee chair Robert Burns commented, “Our understanding of the need for historic preservation to take on a more holistic view of sustainability including social, cultural, and economic equality . calls for us to look closely as to whether current standards are inclusive or exclusive.”38

Historic preservation professionals, architects, and students of those disciplines must contribute to shaping policy, participation models, codes, and standards so that they function better in all communities. In the context of disinvested communities, open dialogues, more flexible standards, and expanded definitions will respect the changes that have taken place over time and encourage preserving with purposes that align with broader use, narrative, or developmental goals in a community.

Barriers in Process: Financing and Delivering Professional Services

A finished product, where buildings and especially houses are concerned, is very much a construct of the so-called first world. If you’ve lived or traveled elsewhere, no doubt you’re familiar with the sight of rebar (steel reinforcing bars) sticking up from the second story of a masonry house. In much of the world, many houses are self-built, but even when they’re not, building one’s house is much more of an incremental process. Rooms are added, floors are added.

One reason for this is financing. The mortgage industry in the United States focuses on the all-at-once. If a homeowner seeks a construction or renovation finance loan, there’s a limited period within which the work must be completed so that the mortgage company has turnkey collateral for the loan. But in parts of the world where housing loans are uncommon or unattainable, construction is self-financed. And self-financing is not done all at once.

Modern architecture and preservation project delivery is based on a triangular structure of participants: the professional (an architect, conservator, or historic preservation specialist), the client (individual, corporation, or nonprofit), and the municipal authorities (the entities that regulate the project and its development). The client initiates the process because the client

brings the funding for the project, whether cash, mortgage, grants, or other financing schemes such as tax credits. The proposed end use for the building shapes the extent of the renovation or rehabilitation project.

The trigger for the cycle and the actualization of a project is funding, and the operation is transactional. The project moves around the triangle in a series of personal, financial, and regulatory transactions. This basic operating structure has been in place since the development of modern building codes and the professionalization of architecture and preservation in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. Although these project delivery norms work well in many contexts, they do not necessarily function well in disinvested communities.

Low property values that result from disinvestment are obstacles for reinvestment, and there is little space to denominate other types of resources. This challenge is an opening to explore and expand ways that clients and communities can work with professionals to acknowledge the expertise and agency of both parties, in smaller increments that require less capital and are more adaptable. Some ingredients for this co-participation are discussed in Chapter 3.

Disinvested communities don’t have the same level of access to financial and technical resources as other communities. Often, multiple systems— including physical infrastructure systems and sociopolitical systems—are broken or functioning suboptimally, and the standards and delivery models for interventions in historic buildings do not always work well. But waiting for the fix often leads to more loss.

I do not believe that widespread demolition is the answer for approaching vacant, abandoned, and distressed buildings in disinvested communities. So far, there’s not a lot of evidence that the immense postrecession demolition efforts have benefited Detroit. Time will tell. But I wonder, along the parallel timeline of a path not taken, what creativity and the Detroit community could have wrought with the raw materials of their history.

Preserving with Purpose explores contextual approaches to existing buildings in disinvested communities as an alternative to demolition, explains why these buildings matter, and what communities and professionals can make of them, together.