Gloria!

9-10 October 2025

Gloria!

Thursday 9 October, 7.30pm Usher Hall, Edinburgh

Friday 10 October, 7.30pm City Halls, Glasgow

POULENC Sinfonietta

POULENC Gloria

Interval of 20 minutes

VIVALDI Gloria

Maxim Emelyanychev conductor

Anna Dennis soprano

Rachel Redmond soprano

Alberto Miguélez Rouco countertenor

SCO Chorus

Gregory Batsleer chorus director Sponsored

SCO, Maxim and SCO Chorus

4 Royal Terrace, Edinburgh EH7 5AB

+44 (0)131 557 6800 | info@sco.org.uk | sco.org.uk

© Christopher Bowen

THANK YOU

Principal Conductor's Circle

Our Principal Conductor’s Circle are a special part of our musical family. Their commitment and generosity benefit us all – musicians, audiences and creative learning participants alike.

Annual Fund

James and Patricia Cook

Visiting Artists Fund

Harry and Carol Nimmo

Anne and Matthew Richards

International Touring Fund

Gavin and Kate Gemmell

Creative Learning Fund

Sabine and Brian Thomson

CHAIR SPONSORS

Conductor Emeritus Joseph Swensen

Donald and Louise MacDonald

Chorus Director Gregory Batsleer

Anne McFarlane

Principal Second Violin

Marcus Barcham Stevens

Jo and Alison Elliot

Second Violin Rachel Smith

J Douglas Home

Principal Viola Max Mandel

Ken Barker and Martha Vail Barker

Viola Brian Schiele

Christine Lessels

Viola Steve King

Sir Ewan and Lady Brown

Principal Cello Philip Higham

The Thomas Family

Sub-Principal Cello Su-a Lee

Ronald and Stella Bowie

Cello Donald Gillan

Professor Sue Lightman

American Development Fund

Erik Lars Hansen and Vanessa C L Chang

Productions Fund

Anne, Tom and Natalie Usher

Bill and Celia Carman

Scottish Touring Fund

Eriadne and George Mackintosh

Claire and Anthony Tait

Cello Eric de Wit

Jasmine Macquaker Charitable Fund

Principal Flute André Cebrián

Claire and Mark Urquhart

Principal Oboe

The Hedley Gordon Wright Charitable Trust

Sub-Principal Oboe Katherine Bryer

Ulrike and Mark Wilson

Principal Clarinet Maximiliano Martín

Stuart and Alison Paul

Principal Bassoon Cerys Ambrose-Evans

Claire and Anthony Tait

Sub-Principal Bassoon Alison Green

George Rubienski

Principal Horn Kenneth Henderson

Caroline Hahn and Richard Neville-Towle

Principal Timpani Louise Lewis Goodwin

Geoff and Mary Ball

Funding Partners

SCO Donors

Diamond

The Cockaigne Fund

Malcolm and Avril Gourlay

John and Jane Griffiths

James and Felicity Ivory

George Ritchie

Tom and Natalie Usher

Platinum

E.C. Benton

Michael and Simone Bird

Silvia and Andrew Brown

David Caldwell in memory of Ann

Dr Peter Williamson and Ms Margaret Duffy

Judith and David Halkerston

David and Elizabeth Hudson

Helen B Jackson

Dr and Mrs Peter Jackson

Dr Daniel Lamont

Graham and Elma Leisk

Professor and Mrs Ludlam

Chris and Gill Masters

Duncan and Una McGhie

Anne-Marie McQueen

James F Muirhead

Robin and Catherine Parbrook

Patrick and Susan Prenter

Mr and Mrs J Reid

Martin and Mairi Ritchie

Hilary E Ross

Elaine Ross

Sir Muir and Lady Russell

Jill and Brian Sandford

Michael and Elizabeth Sudlow

Robert and Elizabeth Turcan

Alan and Sue Warner

Anny and Bobby White

Robert Mackay and Philip Whitley

Finlay and Lynn Williamson

Ruth Woodburn

Gold

Peter Armit

Adam Gaines and Joanna Baker

John and Maggie Bolton

Elizabeth Brittin

Kate Calder

James Wastle and Glenn Craig

Jo and Christine Danbolt

James and Caroline Denison-Pender

Andrew and Kirsty Desson

David and Sheila Ferrier

Chris and Claire Fletcher

James Friend

Iain Gow

Margaret Green

Christopher and Kathleen Haddow

Catherine Johnstone

Julie and Julian Keanie

Gordon Kirk

Janey and Barrie Lambie

Mike and Karen Mair

Roy and Svend McEwan-Brown

John and Liz Murphy

Tom Pate

Maggie Peatfield

Sarah and Spiro Phanos

Charles Platt

Alison and Stephen Rawles

Andrew Robinson

Olivia Robinson

Anne McAlister and Philip Sawyer

Irene Smith

Dr Jonathan Smithers

Ian S Swanson

Ian and Janet Szymanski

John-Paul and Joanna Temperley

Douglas and Sandra Tweddl

Bill Welsh

Catherine Wilson

Neil and Philippa Woodcock

Silver

Roy Alexander

Fiona and Neil Ballantyne

The Batsleer Family

Jack Bogle

Jane Borland

Alan Borthwick

Dinah Bourne

Michael and Jane Boyle

Mary Brady

John Brownlie

Laura Buist

Robert Burns

Sheila Colvin

Lorn and Camilla Cowie

Adam and Lesley Cumming

Dr Wilma Dickson

Seona Reid and Cordelia Ditton

Sylvia Dow

Colin Duncan in memory of Norma Moore

Raymond Ellis

Dr and Mrs Alan Falconer

Sheila Ferguson

Dr William Irvine Fortescue

Dr David Grant

Anne Grindley

Andrew Hadden

J Martin Haldane

Ronnie and Ann Hanna

Roderick Hart

Norman Hazelton

Ron and Evelynne Hill

Philip Holman

Clephane Hume

Tim and Anna Ingold

David and Pamela Jenkins

Margaret Mortimer and Ken Jobling

Ross D. Johnstone

Professor Christopher and Mrs Alison Kelnar

Dr Ian Laing

Geoff Lewis

Dorothy A Lunt

Vincent Macaulay

James McClure in memory of Robert Duncan

Ben McCorkell

Lucy McCorkell

Gavin McCrone

Michael McGarvie

Brian Miller

Alistair Montgomerie

Andrew Murchison

Pamela Andrews and Alan Norton

Gilly Ogilvy-Wedderburn

John Peutherer in memory of Audrey Peutherer

James S Potter

Timothy Barnes and Janet Sidaway

Catherine Steel

John and Angela Swales

Takashi and Mikako Taji

C S Weir

Susannah Johnston and Jamie Weir

We are indebted to everyone acknowledged here who gives philanthropic gifts to the SCO of £300 or greater each year, as well as those who prefer to remain anonymous.

We are also incredibly thankful to the many individuals not listed who are kind enough to support the Orchestra financially on a regular or ad hoc basis. Every single donation makes a difference.

Become a regular donor, from as little as £5 a month, by contacting Hannah Wilkinson on 0131 478 8364 or hannah.wilkinson@sco.org.uk.

“…an orchestral sound that seemed to gleam from within.”

THE SCOTSMAN

HM The King Patron

Donald MacDonald CBE

Life President

Joanna Baker CBE Chair

Gavin Reid LVO

Chief Executive

Maxim Emelyanychev

Principal Conductor

Andrew Manze

Principal Guest Conductor

Joseph Swensen

Conductor Emeritus

Gregory Batsleer

Chorus Director

Jay Capperauld

Associate Composer

© Chris Christodoulou

Your Orchestra Tonight

Information correct at the time of going to print Our Musicians

First Violin

Bogdan Božović

Afonso Fesch

Emma Baird

Amira Bedrush-McDonald

Fiona Alexander

Aisling O’Dea

Sarah Bevan Baker

Kirsty Main

Second Violin

Marcus Barcham Stevens

Gordon Bragg

Hatty Haynes

Michelle Dierx

Rachel Smith

Abigail Young

Kristin Deeken

Catherine James

Viola

Max Mandel

Elaine Koene

Steve King

Rebecca Wexler

Kathryn Jourdan

Edward Keenan

Cello

Philip Higham

Su-a Lee

Donald Gillan

Eric de Wit

Kim Vaughan

Niamh Molloy

Bass

Edward Merritt

Toby Hughes

Ben Havinden-Williams

Maitiú Gaffney

Harp

Eleanor Hudson

Lute/ Theorbo

Eligio Quinteiro

Flute

André Cebrián

Marta Gómez

Caglayan Barbaros

Piccolo

Marta Gómez

Caglayan Barbaros

Oboe

José Masmano Villar

Katherine Bryer

Julian Scott

Cor Anglais

Katherine Bryer

Clarinet

Maximiliano Martín

William Stafford

Bass Clarinet

Calum Robertson

Bassoon

Cerys Ambrose-Evans

Emily Newman

Contrabassoon

Sarah Nixon

Horn

Kenneth Henderson

Harry Johnstone

Andy Saunders

Rachel Brady

Trumpet

Peter Franks

Shaun Harrold

Hedley Benson

Trombone

Duncan Wilson

Nigel Cox

Andy Fawbert

Tuba

Craig Anderson

Timpani

Louise Lewis Goodwin

Chamber Organ

Tom Wilkinson

What You Are About To

Hear

POULENC (1899-1963)

Sinfonietta, FP 141 (1947)

Allegro con fuoco

Molto vivace

Andante cantabile

Très vite et très gai

POULENC (1899-1963)

Gloria, FP 177 (1959-60)

Gloria in excelsis Deo

Laudamus te

Domine Deus

Domine Fili unigenite

Domine Deus, Agnus Dei

Qui sedes ad dexteram Patris

VIVALDI (1678-1741)

Gloria, RV 589 (c. 1715)

Gloria in excelsis Deo

Et in terra pax hominibus

Laudamus te

Gratias agimus tibi

Propter magnam gloriam

Domine Deus

Domine Fili unigenite

Domine Deus, Agnus Dei

Qui tollis peccata mundi

Qui sedes ad dexteram Patris

Quoniam tu solus Sanctus

Cum Sancto Spiritu

It’s hardly surprising that the Gloria – of which you’ll hear two contrasting but similarly exuberant examples in tonight’s concert – has particularly interested composers down the centuries. It represents one of the parts in a religious Mass – specifically the Ordinary of the Mass, which remains largely the same at almost every outing. But it’s a particularly upbeat moment, a hymn of praise to the Creator, one whose brief text kicks off with the angels’ famous Nativity hymn and builds through expressions of love and praise for God and Christ to an invocation of the Holy Spirit. Many composers have set the entire Mass to music, of course, but quite a few – from Salieri to Puccini, John Rutter to Sir James MacMillan – have also zeroed in specifically on the Gloria for individual attention. And if that all sounds terribly liturgical, well, the Gloria’s upbeat spirit has also drawn from composers some of their most joyful, optimistic music, which no doubt strikes a chord with listeners of devout belief and those of none.

Before we get to tonight’s duo of choral Glorias, however, we set the scene for the first of them with music for orchestra alone. ‘Moitié moine, moitié voyou’ (half monk, half street urchin) was French critic Claude Rostand’s pithy assessment of composer Francis Poulenc, a description that neatly sums up the bickering twin sides to his music, both of which we’ll encounter in tonight’s concert. It’s a far broader and more accurate description than that of musicologist Martin Cooper in his 1951 book French Music, who simply described Poulenc as ‘a musical clown of the first order’ – however close to the (partial) truth that appraisal might be.

Poulenc was a Parisian through and through, born into the comfort and security of a well-heeled family whose copious

wealth had come from pharmaceuticals. Without the necessity of finding himself a job, the young Poulenc was able to devote himself to his passion for music, and taught himself virtually unaided as a composer. He delighted in hanging out in Parisian bars and cafés as one of a loose composer collective dubbed Les Six (alongside Georges Auric, Louis Durey, Arthur Honegger, Darius Milhaud and Germaine Tailleferre), a gang that idolised Erik Satie and Jean Cocteau for their iconoclastic aesthetics, and gleefully stuck two fingers up at the serious-minded refinement of the French impressionist composers who had preceded them (though Poulenc maintained a quiet reverence for Claude Debussy). Poulenc merrily pilfered influences from the music hall and the circus, from boulevard cafés and friteries, blending his sarcastic satire with a deep thread of heart-on-sleeve sentimentality, both sides exquisitely delivered with sophistication and impeccable craftsmanship.

Poulenc never wrote a symphony, but his Sinfonietta (literally ‘little symphony’) is probably the closest he came.

But by 1947, the year he wrote his Sinfonietta, Poulenc was aiming for a slightly cooler, more serious approach. His Sinfonietta rode the wave of optimism following the end of the Second World War. It was commissioned by the BBC to celebrate the first anniversary of the Third Programme, predecessor to BBC Radio 3, as one of several works marking the new-found freedom of continental Europe following the conflict.

Poulenc never wrote a symphony, but his Sinfonietta (literally ‘little symphony’) is probably the closest he came. Indeed, it’s almost as if he deliberately stepped back from using that high-flying term for this energetic, light-hearted music, though he generally toned down his high spirits in it. Once he’d finished the work, the then 48-year-old composer admitted to being rather surprised at the gleeful wit and high spirits that remained in his Sinfonietta, and

Francis Poulenc

to being worried that he might have ‘dressed too young for my years’.

Though it might not be called a symphony, the Sinfonietta falls into the conventional four movements we might expect to find in that musical form. A burst of frantic energy kicks off its first movement, though its zingy vivacity gradually dissipates as the movement progresses. And rather than following the tight structure of contrasting themes in a traditional symphonic first movement, Poulenc is instead content to offer a succession of contrasting episodes. He seems to pay tribute to favourite fellow composers in his bustling second movement scherzo – Tchaikovsky’s Pathétique Symphony, or Mendelssohn’s fairy music, or even Mozart – and his slow third movement achieves an almost Mahlerian intensity at times.

There’s no mistaking the influence of Stravinsky in his witty, dashing finale. (Poulenc himself admitted as much, saying: ‘I know very well that I am not the sort of musician who makes harmonic innovations, like Stravinsky, Ravel or Debussy, but I do think there is a place for new music that is satisfied with using other people’s chords.’) But we make a notable return, too, to popular music, in this case sounds that seem to come directly from the music hall, in themes that Poulenc reworked from an early string quartet he’d abandoned. He was forced, however, to reconstruct that music from memory: he felt the original work had failed so badly that he’d flung its score into a Parisian sewer.

From the wit and sparkle of Poulenc’s 1947 Sinfonietta, we turn to – well, quite a lot of the same wit and sparkle in his 1960 Gloria, even if those qualities now have a slightly more

serious intent. The composer was raised a devout Catholic, and rediscovered his faith to some extent with his 1933 Organ Concerto. A turning point came in 1936, however, when his close friend and fellow composer Pierre-Octave Ferroud was killed in a traffic accident in Hungary, aged just 36. Shocked, Poulenc made a pilgrimage to Our Lady of Rocamadour in southern France, prompting a serious turn towards piety and devotion in several overtly religious works, from his solemn Stabat Mater to his deeply moving opera Dialogues des Carmélites, about the gruesome fate of a group of nuns during the French Revolution.

There’s little that’s solemn (or unpleasant) about Poulenc’s Gloria, however. Perhaps taking his inspiration directly from the Gloria text’s feelings of joyful praise, Poulenc wrote music that maintains the dash and sparkling wit of many of his earlier pieces. He later recalled first contemplating a Gloria setting while putting the finishing touches to Dialogues des Carmélites in 1953, and first mentioned the piece in a letter to a friend in April 1959, when he explained he was attempting a setting in the style of Vivaldi, whose own colourful Gloria we’ll hear after the interval (and yes, there are undeniable similarities between both pieces in terms of colour and energy).

The real impetus, however, came with a commission from the US-based philanthropic organisation the Koussevitzky Foundation, which initially requested a symphony (Poulenc replied that it was ‘not my thing’), then an organ concerto (Poulenc told them he’d already written one, and didn’t plan to compose a second), before finally telling the composer to write anything he wanted. The result was the Gloria, premiered on 21 January 1961 in

Some more pious critics, however, accused the composer of sacrilege. It’s true that the Gloriais hardly a deeply devout setting of its religious text, but calling it sacrilegious is probably going far too far.

Boston, by the Boston Symphony Orchestra and Chorus Pro Musica conducted by Charles Münch. After initial worries that the conductor simply didn’t understand his music at all, Poulenc later said his piece had gone down very well, and held it up as his favourite among his choral works.

Some more pious critics, however, accused the composer of sacrilege. It’s true that the Gloria is hardly a deeply devout setting of its religious text, but calling it sacrilegious is probably going far too far. Poulenc himself said he’d been inspired by religious images that themselves showed fun and humour: the frescoes of Florentine Renaissance painter Benozzo Gozzoli, which include angels playfully sticking out their tongues at each other, and memories of seeing Benedictine monks engrossed in playing football. Piety doesn’t have to be all pofaced solemnity, Poulenc seems to be saying. Indeed, his Gloria manages to be

both frivolous and deeply serious, lyrical and dissonant, modestly pious and effusively operatic. Despite its apparent innovations, however, it’s still a deeply conservative piece of music for its times: remember that by 1961, composers including Pierre Boulez and Karlheinz Stockhausen had been sending shockwaves through the musical world for several years with epoch-maching avant-garde creations (from the former’s Le marteau sans maître to the latter’s electronic-based Kontakte).

Poulenc’s zippy rhythmic verve and jocular exuberance play out over the Gloria’s six brief movements. Launched by a grandiose and distinctively Stravinskian theme, ‘Gloria in excelsis Deo’ piles the chorus lines up on each other in their eagerness to sing their praise, generating huge walls of sound with added piquancy from gentle dissonances. A brief interlocking trombone figure introduces the playful ‘Laudamus te’, in

which Poulenc finds a different texture and musical meaning for each of its expressions of praise: ‘Laudamus te, benedicimus te, adoramus te, glorificamus te’. The chorus’ altos kick off the movement’s more solemn, thoughtful central section, ‘Gratias agimus tibi’, but it’s not long before the opening’s high spirits return.

The expressive third movement, ‘Domine Deus, Rex coelistis’, marks the first appearance by the work’s soprano soloist in music of hushed reverence and awe, though an unexpected stray note from the horns and harp make its apparently serene ending slightly more troubled. We return to the earlier sense of playfulness in the very brief ‘Domine fili unigenite’, whose bracing opening figure almost sounds like something Vivaldi might have written.

The soprano soloist returns for the penultimate movement, ‘Domine Deus, Agnus Dei’, which contains some of the Gloria’s richest and most dissonant harmony – entirely in keeping with the text’s pleading for mercy from God. The piece ends in peace and serenity, however, with the lush ‘Qui sedes ad dexteram Patris’, in which fragmented memories of the opening movement’s pomp and grandeur ultimately make way for a brief return from the soprano soloist, and a conclusion that’s heartfelt, sincere and deeply moving.

From Poulenc’s very French 1961 Gloria, we jump back in time around 250 years for tonight’s final piece. And though its musical language might be very different, Vivaldi’s much-loved Gloria shares much of the colour, energy and optimism of Poulenc’s more recent setting. It’s one of the composer’s bestknown and best-loved works, but it’s actually one of at least three settings he made of

the Gloria text. And it’s strange to think that, between Vivaldi’s death and the early 20th century, the piece remained almost entirely unknown. The score was lost until the 1920s, and the Gloria didn’t receive its first revival until 1939, by the Italian composer Alfredo Casella – admittedly in an ‘elaborated’ version. It wasn’t until 1957 that Vivaldi’s restored original version was published and performed.

But its sunny nature and confident, elaborate writing soon gained it a secure place in the choral repertoire. The specific details of the Gloria’s composition are not known, but it was probably written around 1715, and was almost certainly one of the earliest sacred works that Vivaldi wrote while music director and teacher at the Ospedale della Pietà, one of Venice’s four orphanages for girls (who were in fact the illegitimate daughters of noblemen and their mistresses, hence the substantial ‘anonymous’ financial support the institution received). It was at that time that Vivaldi’s operas were starting to gain popularity, and the Gloria reflects the vitality and theatricality of what was then still a new musical form – as well as allowing the composer to indulge in some glorious contrapuntal displays.

While Poulenc divided the Gloria’s text across six movements, Vivaldi goes for no fewer than 12. The opening of ‘Gloria in excelsis Deo’ is one of the most memorable beginnings in all music, with its energetic octave leaps in the orchestra and its choral cries bordering on euphoria. There’s an immediate sense of grandeur and occasion in the monumental choral writing, and the propulsive octaves continue in the orchestra throughout the movement. ‘Et in terra pax hominibus’ comes as a complete contrast, evoking profound sadness with its gentle,

lilting choral melody against a throbbing string accompaniment.

Two sopranos meet in the jaunty duet of ‘Laudamus te’, a piece that wouldn’t be out of place in the opera house. The very short ‘Gratias agimus tibi’ serves as an imposing chordal introduction to the imaginative counterpoint of ‘Propter magnam gloriam’.

‘Domine Deus, Rex coelestis’ is an aria for soprano with violin or oboe, in the lilting rhythm of a siciliana, a sedate Baroque dance often used to depict melancholy emotions. ‘Pater fili unigenite’ brings the chorus back, with distinctive dotted rhythms characteristic of a French overture.

The slow-moving aria for countertenor with bass obbligato ‘Domine Deus, Agnus Dei’ is a hushed creation with several choral interjections that seem intended to bring the soloist out of their introspection. ‘Qui tollis

It’s one of the composer’s best-known and best-loved works, but it’s actually one of at least three settings he made of the Gloria text.

peccata mundi’ is a brief, brooding choral introduction to the countertenor aria ‘Qui sedes ad dexteram Patris’, a sprightly song characterised by long-held notes in the solo vocal part, in contrast with its scampering string lines.

The penultimate movement, ‘Quoniam tu solus sanctus’, presents the work’s memorable opening music in a simplified form in preparation for its conclusion in ‘Cum Sancto Spiritu’. This final movement is in fact an arrangement of the ending of a Gloria composed in 1708 by the elder Veronese composer Giovanni Maria Ruggieri, a figure little remembered today but held in high esteem by Vivaldi. The younger composer improved on the original, adding new trumpet parts and emphasising the role of the orchestra, and its sparkling counterpoint brings his Gloria to a suitably celebratory conclusion.

© David Kettle

Antonio Vivaldi

Libretto

POULENC (1899-1963)

Gloria, FP 177 (1959)

Gloria in excelsis Deo et in terra pax homínibus bonæ voluntatis.

Laudamus te, benedicimus te, adoramus te, glorificamus te, gratias agimus tibi propter magnam gloriam tuam.

Domine Deus, Rex cælestis, Deus Pater omnipotens.

Domine Fili unigenite, Jesu Christe.

Domine Deus, Agnus Dei, Filius Patris, qui tollis peccata mundi, miserere nobis; qui tollis peccata mundi, suscipe deprecationem nostram.

Qui sedes ad dexteram Patris, miserere nobis.

Quoniam tu solus Sanctus, tu solus Dominus, tu solus Altissimus, Jesu Christe, cum Sancto Spíritu: in gloria Dei Patris. Amen.

Glory to God in the highest, and on earth peace to people of good will.

We praise you, we bless you, we adore you, we glorify you, we give you thanks for your great glory.

Lord God, heavenly King, O God, the almighty Father.

Lord Jesus Christ, Only Begotten Son.

Lord God, Lamb of God, Son of The Father, who takes away the sins of the world, have mercy on us; you take away the sins of the world, receive our prayer.

You are seated at the right hand of the Father, have mercy on us.

For you alone are the Holy One, you alone are the Lord, you alone are the Most High, Jesus Christ, with the Holy Spirit, in the glory of God the Father. Amen.

VIVALDI (1678-1741)

Gloria, RV 589 (c. 1715)

Gloria in excelsis Deo.

Et in terra pax hominibus bonæ voluntatis.

Laudamus te, benedicimus te, adoramus te, glorificamus te.

Gratias agimus tibi. Propter magnam gloriam tuam.

Domine Deus, Rex cælestis, Deus Pater omnipotens.

Domine Fili unigenite, Jesu Christe.

Domine Deus, Agnus Dei, Filius Patris.

Qui tollis peccata mundi, miserere nobis.

Qui tollis peccata mundi, suscipe deprecationem nostram.

Qui sedes ad dexteram Patris, miserere nobis.

Quoniam tu solus Sanctus, tu solus Dominus, tu solus Altissimus, Jesu Christe.

Cum Sancto Spíritu: in gloria Dei Patris. Amen.

Glory to God in the highest.

And on earth peace to people of good will.

We praise you, we bless you, we adore you, we glorify you.

We give you thanks. For your great glory.

Lord God, heavenly King, O God, the almighty Father.

Lord Jesus Christ, Only Begotten Son.

Lord God, Lamb of God, Son of The Father. Who takes away the sins of the world, have mercy on us.

You take away the sins of the world, receive our prayer.

You are seated at the right hand of the Father, have mercy on us.

For you alone are the Holy One, you alone are the Lord, you alone are the Most High, Jesus Christ.

with the Holy Spirit, in the glory of God the Father. Amen.

Conductor Maxim

Emelyanychev

Maxim Emelyanychev has been Principal Conductor of the Scottish Chamber Orchestra since 2019. He is also Chief Conductor of period-instrument orchestra Il Pomo d’Oro, and from the 2025/26 season he becomes Principal Guest Conductor of the Swedish Radio Symphony Orchestra.

Born in Nizhny Novgorod, Emelyanychev made his conducting debut at the age of 12, and later joined the class of eminent conductor Gennady Rozhdestvensky at the Moscow Conservatoire.

Emelyanychev was initially appointed as the SCO’s Principal Conductor until 2022, and the relationship was later extended until 2025 and then until 2028. He has conducted the SCO at the Edinburgh International Festival and the BBC Proms, as well as on several European tours and in concerts right across Scotland. He has also made three recordings with the SCO, of symphonies by Schubert and Mendelssohn (Linn Records).

Emelyanychev has also conducted many international ensembles including the Berlin Philharmonic, Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra, Orchestra dell'Accademia Nazionale di Santa Cecilia, Deutsches Symphonie-Orchester Berlin, Rotterdam Philharmonic Orchestra, Finnish Radio Symphony Orchestra, Seattle Symphony and Orchestra of the Age of Enlightenment. In the opera house, Emelyanychev has conducted Handel’s Rinaldo at Glyndebourne, the same composer’s Agrippina as well as Mozart’s The Magic Flute at the Royal Opera House, Covent Garden, and Mozart’s Die Entführing aus dem Serail at the Opernhaus Zürich. He has also conducted Mozart’s Die Zauberflöte and Così fan tutte with the SCO at the Edinburgh International Festival. He has collaborated closely with US soprano Joyce DiDonato, including international touring and several recordings.

Among his other recordings are keyboard sonatas by Mozart, and violin sonatas by Brahms with violinist Aylen Pritchin. He has also launched a project to record Mozart’s complete symphonies with Il Pomo d’Oro. In 2019, he won the Critics’ Circle Young Talent Award and an International Opera Award in the newcomer category. He received the 2025 Herbert von Karajan Award at the Salzburg Easter Festival.

ANNA DENNIS

Anna Dennis studied at the Royal Academy of Music. She was the recipient of the 2023 Royal Philharmic Society’s Singer award.

Her opera performances include Katie Mitchell’s New Dark Age at the Royal Opera House, Purcell’s The Fairy Queen at Drottningholms Slottsteater in Stockholm, Handel’s Rodelinda at the Göttingen Handel Festspiel, Mozart’s Idomeneo directed by Graham Vick at Birmingham Opera Company, Damon Albarn’s Dr Dee at English National Opera, and roles in all three Monteverdi operas during John Eliot Gardiner’s world tour of the trilogy. She recently created the title role of Violet in Tom Coult’s debut opera, premiered at the Aldeburgh festival, and multiple roles in Sir David Pountney's Purcell pasticcio Masque of Might for Opera North.

In concert she has sung with the Scottish Chamber Orchestra , Orchestra of St Luke’s in New York, the Australian Chamber Orchestra, Birmingham Contemporary Music Group, Orquestra Gulbenkian, les Violons du Roy, Britten Sinfonia, and Sinfonietta Riga. She has sung Britten’s War Requiem at the Berlin Philharmonie and Thomas Ades’ Life Story, accompanied by the composer, at New York’s White Light Festival. Recent highlights have included performing Antony Burgess setting of TS Eliot’s The Wasteland with Benedict Cumberbatch and Britten Sinfonia at the Charleston Festival, Bach’s Mein Herze Schwimmt im Blut with Kristian Bezuidenhout in Riga, Haydn’s Jahreszeiten with Düsseldorfer Sinfoniker under Adam Fischer, and Handel’s Judas Maccabeus with AKAMUS at the Berlin Philharmonie.

Her numerous recordings include Elena Langer’s Landscape with Three People, the Grammynominated Kastalsky Requiem with the Orchestra of St Luke’s under Leonard Slatkin, and Handel’s Amadigi di Gaula with Early Opera Company under Christian Curnyn.

In the coming season she will sing Queen of the Night/The Magic Flute for Opera North, Nono's Canti di Vita e d'Amore with BBC Symphony Orchestra, Handel's Orlando with the Academy of Ancient Music, and also sang Mozart Mass in C minor with the Scottish Chamber Orchestra earlier in the Season.

For full biography please visit sco.org.uk

Soprano

RACHEL REDMOND

Described as an “impressively silken soprano” (The Times) and “resplendent” (The New York Times) Rachel Redmond began her career with the prestigious Jardin des Voix, performing with Les Arts Florissants under the direction of William Christie and Paul Agnew in France, Spain and New York. At William Christie’s invitation she made her début at the Opera Comique as Iris in Lully’s Atys, and performed Irene, Léontine and Flore in Robert Carsen’s production of Les Fetes Venitiennes at the Opera Comique, The Théâtre du Capitole de Toulouse and Brooklyn Academy of Music. She subsequently made her début at the Théâtre du Châtelet as Loena in La belle Hélène.

Her considerable concert repertoire also includes, Vivaldi’s Gloria, Handel’s Dixit Dominus, Jeptha, Neun Deutsche Arien, Samson, Il Trionfo del Tempo e del Disonganno, and Saul, Bach St Matthew Passion and Ascention Oratorio, Graupner Diese Zeit ist ein Spiel der Eitelkeit, Charpentier Les plaisirs de Versailles, Les pastorelles de Noël and La descente d’Orphée aux enfers, Brockes Passion by Reinhard Keiser, Beethoven Mass in C, Brahms Requiem, Bernstein Chichester Psalms, Karl Jenkins Gloria, and Orff Carmina Burana. She has performed as a soloist with the European Union Baroque Orchestra, Amsterdam Concertgebouw Orchestra, Norwegian Chamber Orchestra, Royal Liverpool Philharmonic Orchestra, BBC Scottish Symphony Orchestra, Dunedin Consort, The English Concert, Helsinki Baroque Orchestra, Barokkanerne-Norwegian Baroque Ensemble, and in Aldeburgh, London’s Wigmore Hall and the Auditorio Manuel de Falla in Granada.

Highlights this season for Rachel Redmond include Dorinda in Orlando with the Academy of Ancient Music, Aminta in Vivaldi’s L’Olimpiade with Irish National Opera, Messiah with Tafelmusik, St John Passion with Les Arts Florissants, Galatea in Acis and Galatea and Venus in Venus and Adonis with Ensemble Masques.

Rachel Redmond was born in Glasgow and sang in the Junior Chorus of the Royal Scottish National Orchestra before studying at the Music School of Douglas Academy, the Royal Conservatoire of Scotland (RCS), and the Guildhall School of Music and Drama. She was awarded the Florence Veitch Ibler prize at the RCS for oratorio performance.

For full biography please visit sco.org.uk

Soprano

©

Chris Wallace

ALBERTO MIGUÉLEZ ROUCO

Alberto Miguélez Rouco was born in La Coruña (Spain) in 1994, where he studied singing with tenor Pablo Carballido del Camino and Piano with Cristina López. In 2012 he began his singing studies at the Musik Akademie Basel (Schola Cantorum Basiliensis), where he studied with the mezzosoprano Rosa Domínguez, finishing his Master Degrees in 2017 and 2019. He also studied harpsichord and basso continuo with Francesco Corti, Giorgio Paronuzzi and Jesper Christensen.

As a soloist in oratorio he has sung Caldara’s Maddalena ai piedi di Cristo (René Jacobs), Bach’s Johannes-Passion (René Jacobs and Bach Vereniging), Händel’s Israel in Egypt (René Jacobs), Messiah, Ode for the birthday of Queen Anne, and Il trionfo del Tempo e del Disinganno (Disinganno) under the direction of Paul Agnew (Trondheim Baroque Festival), Pasquini’s Il San Vito (at Boston Early Music Festival), Michael Haydn’s Requiem in c-minor, Hasse’s Miserere in c-minor, Monteverdi’s Vespro della Beata Vergine, Saint-Saëns’ Oratorio de Noël, Mozart’s Coronation Mass, Sparrow Mass and Trinitas Mass, Pergolesi’s Stabat Mater, Vivaldi’s Gloria, Magnificat and Beatus Vir, Charpentier’s Te Deum and Traetta’s Stabat Mater.

He regulary attends to masterclasses with renowned singers and teachers like Margreet Honig, Sara Mingardo, Mariella Devia, Philippe Jaroussky, Valerie Guillorit, Christine Schäfer, Alessandro de Marchi, Sophie Daneman and Maria Cristina Kiehr, and has worked with conductors like René Jacobs, William Christie, Paul Agnew, Christophe Rousset, Gabriel Garrido, Lionel Sow or Josep Pons. He has performed with orquestras such as Les Arts Florissants, Freiburger Barockorchester, Le Concert des Nations, Hesperion XXI, Trondheim Baroque Orchestra, Les talens Lyriques, Café Zimmermann, la Orquesta Sinfónica de Galicia, Ensemble Elyma, Musica Fiorita and Ensemble Semura Sonora. Since 2020 he has been a member of Philippe Jaroussky’s voice Academy.

In 2018 he founded his own ensemble Los Elementos, with whom he recorded José de Nebra’s baroque zarzuela Vendado es Amor no es ciego, in September 2019 for Glossa. In 2020 he recorded his first solo album, Cantadas, with music by José de Nebra and Francesco Corselli, and in 2021 they recorded Nebra’s Donde ay violencia, no ay culpa

For full biography please visit sco.org.uk

© Susanna Drescher

GREGORY BATSLEER

The Scottish Chamber Orchestra is delighted to announce that Greg’s contract as SCO Chorus Director has been extended until August 2028. For more information visit www.sco.org.uk/news.

Gregory Batsleer is acknowledged as one of the leading choral conductors of his generation, winning widespread recognition for his creativity and vision. Since taking on the role of SCO Chorus Director in 2009 he has led the development of the Chorus, overseeing vocal coaching, the SCO Young Singers’ Programme and the emergence of regular a capella concerts. As well as preparing the Chorus for regular performances with the Orchestra, he has directed their successful appearances at the Edinburgh International Jazz, East Neuk, Glasgow Cathedral and St Andrews Voices Festivals, at Greyfriars Kirk and on the SCO Summer Tour.

In 2021 Gregory took up the position of Festival Director for the London Handel Festival. He leads the programming and development of the Festival, fulfilling its mission to bring Handel’s music to the widest possible audiences. He has been Artistic Director of Huddersfield Choral Society since 2017 and was Chorus Director with the Royal Scottish National Orchestra from 2015-2021.

As guest conductor, Gregory has worked with many of the UK’s leading orchestras and ensembles. Recent highlights include performances with the Royal Northern Sinfonia, RSNO, Hallé Orchestra, Black Dyke Band, National Youth Choir of Great Britain, Orchestra of Opera North, Manchester Camerata, SCO and Royal Liverpool Philharmonic.

From 2012 to 2017, he was Artistic Director of the National Portrait Gallery’s Choir in Residence programme, the first ever in-house music programme of any gallery or museum in the world. He has curated and devised performances for the Southbank Centre, Wilderness Festival and Latitude and collaborated with leading cultural figures across a variety of different art forms. Gregory is the cofounder and conductor of Festival Voices, a versatile ensemble dedicated to cross-art collaboration.

Gregory sits on the board of Manchester Camerata as a non-executive director. His outstanding work as a choral director was recognised with the 2015 Arts Foundation’s first-ever Fellowship in Choral Conducting.

Gregory’s Chair is kindly supported by Anne McFarlane

27-28 November, 7.30pm

L’Enfance du Christ

Maxim Emelyanychev Conductor

Paula Murrihy Mary

Andrew Staples Narrator, Centurion

Roderick Williams Joseph, Polydorus

Callum Thorpe Herod, Ishmaelite Father

SCO Chorus

Gregory Batsleer chorus director

LEARN MORE

SCO CHORUS

The Scottish Chamber Orchestra Chorus, under the direction of Gregory Batsleer since 2009, has built a reputation as one of Scotland’s most vibrant and versatile choirs. Widely regarded as one of the finest orchestral choruses in the UK, it celebrated its 30th anniversary in 2021. Members enjoy the unique opportunity of performing with one of the world’s leading chamber orchestras, working with international conductors including Maxim Emelyanychev, Andrew Manze, Harry Christophers, Richard Egarr, Václav Luks and Sir James MacMillan.

The Chorus appears regularly with the Orchestra in Scotland’s major cities. Recent concerts have covered a wide range of music including Bach’s Mass in B minor, Brahms’ Requiem, Haydn’s Creation and a rare performance of Vaughan Williams’ Flos Campi. A performance of Sir James MacMillan’s Seven Last Words from the Cross was a highlight of the 2024-25 Season. SCOC has given the premiere performances of several SCO Commissions for choir and orchestra including The Years by Anna Clyne (SCO Associate Composer 2019-2022) and James MacMillan’s Composed in August; the coming season will see the premiere of The Language of Eden by SCO Associate Composer Jay Capperauld.

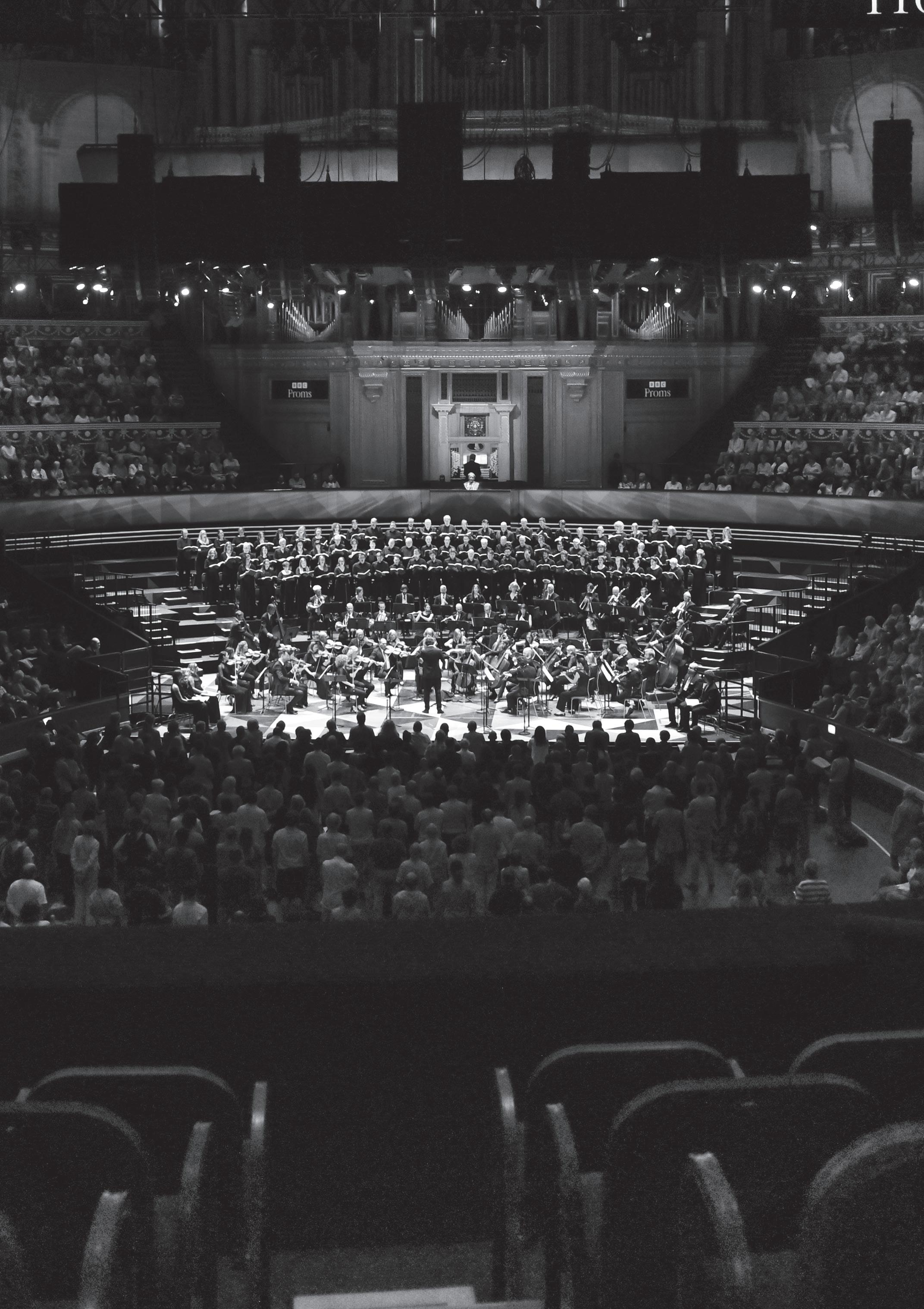

The SCO Chorus also performs a capella, both digital and live, in music ranging from Tallis and Purcell to new work by Anna Clyne and Jay Capperauld. Its annual Christmas concerts at Edinburgh’s Greyfriars Kirk have established themselves as a Season highlight; the Chorus also enjoys appearing on the SCO’s Summer Tour. Other notable out-of-Season appearances have included criticallyacclaimed performances with the SCO at the BBC Proms in Handel’s Jephtha in 2019 and in Mendelssohn's Elijah in 2023. The Chorus appeared with Maxim Emelyanychev and SCO in a semi-staged performance of Mozart’s Die Zauberflöte at the 2023 Edinburgh International Festival, resulting in re-invitations for Così fan tutte in 2024 and La Clemenza di Tito in 2025.

SCOC’s Young Singers' Programme was established in 2015 to nurture and develop aspiring young singers. It is designed for young people with a high level of choral experience and ambitions to further their singing with a world-class ensemble.

Further information at sco.org.uk

The SCO Chorus Young Singers' Programme is kindly supported by the Baird Educational Trust.

© Christopher Bowen

YOUR CHORUS TONIGHT

SOPRANO

Emma Aitken

Kirstin Anderson

Naomi Black

Nancy Burns

Mairi Day

Joanne Dunwell

Liberty Emeny

Emily Gifford

Gregory Batsleer

Chorus Director

Stuart Hope

Associate Chorusmaster

Emma Morwood

Voice Coach

Susan White

Chorus Manager

* Young Singers' Programme

Alice Higgins

Lisa Johnston

Florence Kaiser*

Emily Kemp*

Katie McGlew

Anna Morris*

Jenny Nex

Alison Williams

ALTO

Dinah Bourne

Shona Banks

Sarah Campbell

Gill Cloke

Judith Colman

Jennie Gardner

Claire Goodenough

Melissa Humphreys

Elaine McAdam

Elizabeth McColl

Hilde McKenna

Charlotte Perkins

Linda Ruxton

Olivia Smith*

TENOR

Matthew Andrews

Magnus Bushby*

Colin French

Theodore Hill

Fraser Macdonald

Keith Main

Michael Scanlon

Paul Vaughan

Rory Wilson

BASS

David Paterson

Donald MacLeod

Douglas Nicholson

Fraser Riddell

Gavin Easton

Hugh Hillyard-Parker

Jason Orringe

Orlando Griffiths*

Peter Silver

Richard Hyder

Richard Murphy

Roderick Wylie

Stephen Todd

Taliesin Liston-Smith*

Scottish Chamber Orchestra

The Scottish Chamber Orchestra (SCO) is one of Scotland’s five National Performing Companies and has been a galvanizing force in Scotland’s music scene since its inception in 1974. The SCO believes that access to world-class music is not a luxury but something that everyone should have the opportunity to participate in, helping individuals and communities everywhere to thrive. Funded by the Scottish Government, City of Edinburgh Council and a community of philanthropic supporters, the SCO has an international reputation for exceptional, idiomatic performances: from mainstream classical music to newly commissioned works, each year its wide-ranging programme of work is presented across the length and breadth of Scotland, overseas and increasingly online.

Equally at home on and off the concert stage, each one of the SCO’s highly talented and creative musicians and staff is passionate about transforming and enhancing lives through the power of music. The SCO’s Creative Learning programme engages people of all ages and backgrounds with a diverse range of projects, concerts, participatory workshops and resources. The SCO’s current five-year Residency in Edinburgh’s Craigmillar builds on the area’s extraordinary history of Community Arts, connecting the local community with a national cultural resource.

An exciting new chapter for the SCO began in September 2019 with the arrival of dynamic young conductor Maxim Emelyanychev as the Orchestra’s Principal Conductor. His tenure has recently been extended until 2028. The SCO and Emelyanychev released their first album together (Linn Records) in 2019 to widespread critical acclaim. Their second recording together, of Mendelssohn symphonies, was released in 2023, with Schubert Symphonies Nos 5 and 8 following in 2024.

The SCO also has long-standing associations with many eminent guest conductors and directors including Principal Guest Conductor Andrew Manze, Pekka Kuusisto, François Leleux, Nicola Benedetti, Isabelle van Keulen, Anthony Marwood, Richard Egarr, Mark Wigglesworth, Lorenza Borrani and Conductor Emeritus Joseph Swensen.

The Orchestra’s current Associate Composer is Jay Capperauld. The SCO enjoys close relationships with numerous leading composers and has commissioned around 200 new works, including pieces by Sir James MacMillan, Anna Clyne, Sally Beamish, Martin Suckling, Einojuhani Rautavaara, Karin Rehnqvist, Mark-Anthony Turnage, Nico Muhly and the late Peter Maxwell Davies.

© Christopher Bowen

Support Us

Each year, the SCO must fundraise around £1.2 million to bring extraordinary musical performances to the stage and support groundbreaking education and community initiatives beyond it.

If you share our passion for transforming lives through the power of music and want to be part of our ongoing success, we invite you to join our community of regular donors. Your support, no matter the size, has a profound impact on our work – and as a donor, you’ll enjoy an even closer connection to the Orchestra.

To learn more and support the SCO from as little as £5 per month, please contact Hannah at hannah.wilkinson@sco.org.uk or call 0131 478 8364.

SCO is a charity registered in Scotland No SC015039.

Photo: Stuart Armitt

The