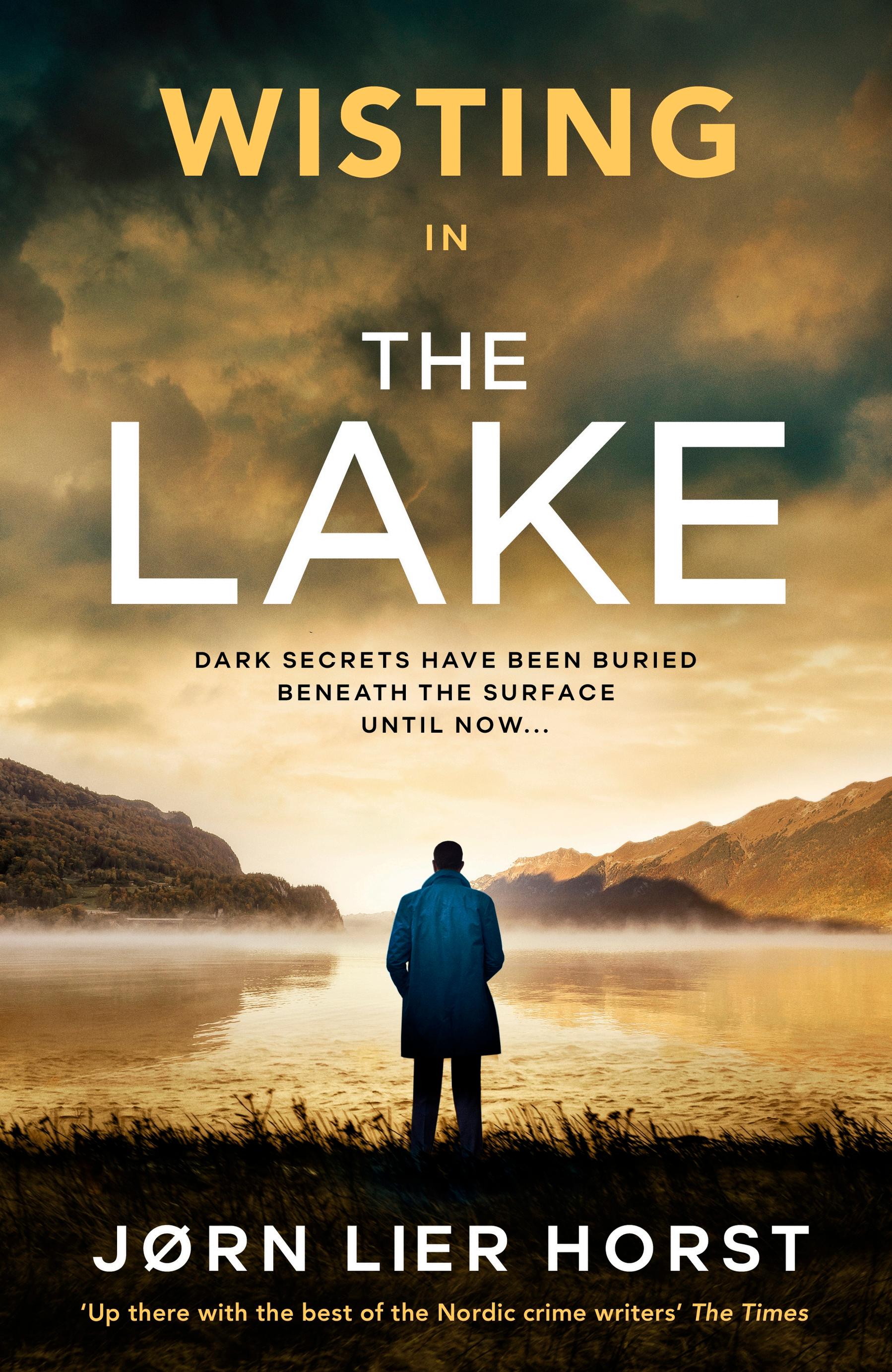

The Lake

jørn lier horst

Translated by Anne Bruce

PENGUIN MICHAEL JOSEPH

UK | USA | Canada | Ireland | Australia India | New Zealand | South Africa

Penguin Michael Joseph is part of the Penguin Random House group of companies whose addresses can be found at global.penguinrandomhouse.com

Penguin Random House UK, One Embassy Gardens, 8 Viaduct Gardens, London SW11 7BW penguin.co.uk

Published in Great Britain by Penguin Michael Joseph 2025

First published in Norway by Bonnier Norsk Forlag as Tørt land 2024

Copyright © Jørn Lier Horst, 2025

English translation copyright © Anne Bruce, 2025

The moral right of the author has been asserted

Penguin Random House values and supports copyright. Copyright fuels creativity, encourages diverse voices, promotes freedom of expression and supports a vibrant culture. Thank you for purchasing an authorized edition of this book and for respecting intellectual property laws by not reproducing, scanning or distributing any part of it by any means without permission. You are supporting authors and enabling Penguin Random House to continue to publish books for everyone. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner for the purpose of training artificial intelligence technologies or systems. In accordance with Article 4(3) of the DSM Directive 2019/790, Penguin Random House expressly reserves this work from the text and data mining exception

Set in 13 5/16pt Garamond MT Typeset by Falcon Oast Graphic Art Ltd Printed and bound in Great Britain by Clays Ltd, Elcograf S.p.A.

The authorized representative in the EEA is Penguin Random House Ireland, Morrison Chambers, 32 Nassau Street, Dublin D02 YH68

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

hardback isbn: 978–0–241–53385–7 trade paperback isbn: 978–0–241–53386–4

Penguin Random House is committed to a sustainable future for our business, our readers and our planet. This book is made from Forest Stewardship Council® certified paper.

The Lake

The water level had dropped by more than a metre since he had last been here and an old rowing boat had surfaced. It lay on its side, the hull peppered with holes, partially submerged in silt, the stern trapped in the murky lake.

Evert Harting perched on the car tailgate, pulling on his boots. The air was still. He straightened the brim of his baseball cap and sat looking out over Lake Farris. The surface was almost flat, undisturbed by ripples. The reflection of the sun’s rays was so strong that he had to avert his eyes.

Along the shore, the retreating water had left a broad, colourless strip, a smooth and placid stretch of dry land.

Fastening his utility belt, he lifted the metal detector from the car boot and swept it across the rear wheel to test it out. A high-pitched beep sounded when the sensing probe closed in on the metal rim, letting him know that the onscreen signals were working exactly as they should.

A long-billed bird took flight as he strode towards the search area. The dried-up clay lake-bed had split open, and a network of cracks now zigzagged across the entire expanse of foreshore. Here and there, rocks and stones protruded from the surface, dotted in some places with clumps of dried, withered rushes.

The thin crust of earth broke, flaking off under his feet. Once he had located the boulder where he had last stopped, he began his methodical work. The footprints from his previous visit were still visible. He walked parallel to these as far as

the cliff edge, where he turned around and retraced his steps. In the background, he could hear the distant hum of traffic crossing the motorway bridge to the south.

The detector registered a find – the high-frequency tone told him something made of light metal was buried in the ground. He had some idea of what it would be and used his foot to scrape back the earth, uncovering an empty beer can. The whipped-up dust irritated the back of his throat. Walking on a little, he adjusted the sensitivity and continued his search. What he was hoping to find was some trace of the ancient Fresjeborgen, a fortress said to have been situated somewhere here along the shoreline, destroyed by a flood at some point in the seventeenth century. It had apparently been endowed with both maidens’ bowers and iron spires, but he would be happy to find as little as an old hand-forged nail.

He took a few mouthfuls from the water bottle attached to his belt before trudging on.

Several broken planks of wood, stained with deep-rooted green algae and partly rotted, criss-crossed the parched lake-bed.

He swung the sensing probe over them but heard no beep in response.

Beside the rock face that bounded the search area, he saw some sunken driftwood. He manoeuvred the probe in between a grey timber post and a gnarled tree root. There was an immediate beep, an oscillating tone, and the onscreen signal indicated copper or some similar low-conducting metal.

Laying down the detector, he moved the root aside. A fishing lure, coated in verdigris, was caught in one of the twisted tree roots.

He was equally excited each time the detector produced a strong signal, but mostly it turned out to be nothing but junk.

Once he had found a Danish silver coin from 1642, from the reign of Christian IV, lying at the edge of a field beside a ravine in Stokke. Another time he had come across a silver finger bowl that had been dated to the late 1800s.

He left the lure hanging there and walked back alongside his footprints, making sure to swing the sensing probe in such a way that it overlapped his previous route. The sun was burning his neck, and perspiration made the back of his shirt feel sticky.

With each lap he came closer to the lake. He reckoned he had three lengths left when he heard another beep from the sensor. The indicator pointed to gold.

Evert Harting felt his pulse race. He turned the sensing probe round in circles to home in on his find. The fluctuating signal was unmistakable. According to the onscreen information, the object was located relatively deep, between twenty and thirty centimetres beneath the surface.

He could hear the loudest beep above a narrow crack in the dry lake-bed. Marking the spot with the edge of the probe, he laid aside the detector and pushed his cap back, wiping sweat from his brow with his shirtsleeve.

He unhooked the trowel he kept tucked into his belt before kneeling and digging up a couple of scoops and then starting to filter the crumbly earth, filled with small pebbles and plant residues, through his fingers.

He knew he would have to delve deeper and continued to work his way painstakingly downwards. Eventually the clay grew damp and lumpy and at this stage he laid the trowel aside and took out his pinpointer. It beeped and vibrated in the palm of his hand when he moved it towards the base of the hole. Whatever he’d found seemed to be buried at the far edge of the pit he had excavated.

Drops of perspiration stung his eyes. Blinking them away, he grabbed a fistful of earth and crumbled it in his hand. Nothing there. He tried again and this time felt his fingers snag on something. When he raised his hand, he brought with it an object that looked like thread. A gold chain.

Coiling it in his palm, he flipped it over into his other hand and then back again to remove the grains of earth.

A delicate necklace, maybe forty centimetres in length. A pendant dangled from the middle of the chain. The letter A. The link closest to the catch was damaged, as if the chain had snapped.

A cool breeze stirred up dust as Evert Harting clenched his fist around the gold chain and got to his feet. He spotted a kayaker making his way across the lake. On the opposite side, the sun reflected off moving vehicles and he thought he could make out figures below the steep mountainside facing the lake.

He stood there for a long time, impassively watching, before swallowing hard and gazing down at his hand again. He carefully uncurled his fingers.

He had only seen a necklace like this once before, in newspaper photographs – and that must have been a few years ago now.

At the top of the A, a tiny hole had been drilled to attach it to the chain. The same process had been followed again on the right, at the base of the letter, allowing it to hang at a slight angle on the wearer’s neck.

With his thumb, he rubbed the letter clean and used his nail to pick off some soil from the link where it was attached to the chain. Then he tucked the necklace into his breast pocket and tamped down the earth with his foot, back into the hole he had dug.

Following the directions he’d been given over the phone, Wisting found the right turn-off. Dense growth of deciduous trees lined both sides of the road, with sunlight slanting through the branches and casting dappled shadow on the rough gravel track ahead.

He did not have to drive far before he spotted the others. The vehicles were parked in a wide semicircle in a clearing beside Lake Farris.

Clouds of dust whirled around his car as he braked and drew to a halt. Nils Hammer stood at the verge alongside two young, uniformed officers.

Wisting pushed the car door open and stepped out. The overheated engine was making a ticking noise at his back.

Hammer drank deeply from a bottle of water. ‘I thought you’d want to see it for yourself before any action was taken,’ he said.

The police officers moved aside and Wisting walked forward to the low wooden fence to look over the edge. A third officer stood five metres below them on the shore. Everything previously hidden by the water was now exposed and clearly visible. He caught sight of an old fridge, a cooker, a lawnmower, several coils of rusty barbed wire, old roof tiles, an assortment of unidentifiable pieces of scrap metal and, the focus of their attention, a motorbike.

‘You were the one who registered the missing vehicle,’ Hammer said. ‘LU 4813. Yamaha DT, 100 cc.’

He could make out footprints on the dry sludge of the lakebed, surrounding the heap of junk. Someone had gone right up to the motorbike and wiped the number plate, but apart from that, everything appeared to have been left undisturbed.

Wisting turned around and gazed back along the track he had left behind him. The motorbike was about six metres from shore. Its speed must have been so excessive that the rider had been unable to clear the bend.

‘The landowner built the fence seven years ago,’ Hammer explained, ‘to prevent people from dumping rubbish here. He was the one who reported it.’

The sun glinted on the chrome-plated exhaust pipe.

‘Locals call this place the Yeller,’ Hammer went on. ‘The folk who lived nearby stood here and shouted for the ferry whenever they wanted to travel up to Siljan or down into town.’

He pointed at the remains of a few mooring posts on the mountainside.

‘How do I get down there?’ Wisting asked.

One of the police officers pointed out the route they had taken, via a dried-up stream on the right-hand side of the small plateau. Wisting pushed branches aside as he embarked on the rugged descent, with Hammer following close on his heels.

The hillside was steep and Wisting had to catch hold of a pliable branch for the first few metres before scrabbling for footholds on the final stretch.

The officer who had already scrambled down came forward to greet them. He was one of the young temporary recruits employed during the summer months.

‘There’s a safe here too,’ he said, pointing to it.

Wisting lifted his hand to shade his eyes from the blinding

sunlight. Half-buried in the heap of debris, he could make out a grey steel safe, partly concealed by twigs hooked on to the coils of barbed wire. A dented car bumper protruded halfway up beside it, as well as other discarded car parts and something that looked like an electric heater.

‘Well spotted,’ Wisting said, taking note of the raw recruit’s response to the compliment.

‘Must have been stolen and dumped here after being ransacked,’ he said.

Wisting agreed. ‘We’ll take a look at it later.’

They navigated their way towards the motorbike. The grey clay of the lake-bed, baked hard by the sun, crunched under their feet.

All of a sudden, Wisting’s feet broke through the brittle crust of earth and he sank up to mid-calf. He was forced to use a rusty washing machine for support. Water trickled in and filled the hole as he pulled his feet out, but he managed to avoid getting soaked.

The motorbike, and still-seated rider, lay on its side with the front wheel completely buried. A black leather jacket partially covered the fuel tank and handlebars. A pair of disintegrating blue denim jeans and a collection of grey bones poked out of a boot.

Wisting skirted round before taking up position in front of the motorbike. The rider’s helmet had fallen half a metre away with the visor down, and he could see pale vertebrae spilling from the neck opening.

‘It’s almost eight years to the day since he disappeared,’ Hammer commented.

Wisting nodded as he spoke the name to himself. Morten Wendel. Sixteen years old. His life destroyed in one fatal summer.

‘What are your thoughts?’ Hammer asked. ‘An accident, or did he do this deliberately?’

‘I don’t know,’ Wisting answered. ‘Everything about the case points to the latter.’

Taking a few steps towards the motorbike, he crouched down and moved the left sleeve of the stiff leather jacket to one side. On the handlebar grips, fragments of bone were entangled in what looked like the remains of black rubber gloves.

Hammer gave a loud sigh and swore under his breath.

‘What is it?’ asked the young officer beside him.

‘Tape,’ was Hammer’s terse reply.

The young officer still didn’t understand.

‘He’d taped his hand to the handlebar to make sure he couldn’t change his mind,’ Hammer explained. ‘When he started to ride out, there was no way back. He had to stay with the bike all the way to the bottom of the lake.’

The young officer looked queasy at the idea.

‘I’ve alerted the forensics team,’ Hammer said. ‘They’re on their way.’

Standing up again, Wisting turned aside and stared out across the water. A kayak was approaching from the southern shore of the lake, the kayaker propelling himself forward with precise movements and rhythmic strokes of the oars.

It was 13:48 exactly, on Monday 13 July, scarcely halfway through summer.

Evert Harting caught sight of the two empty plastic containers when he opened the car boot and took out the metal detector. Damn, he should have filled them while he was on the road, but it had slipped his mind entirely.

He left them where they were. They had enough water to last until tomorrow. This was the first time the well had gone dry and the pipes were making only a hollow sound. At first, he’d thought the electric pump had let them down, but he was relieved to avoid the cost of repairing that when he realized the well had quite simply dried up.

Ella was sitting in the shade on the covered verandah with one of her crosswords.

‘I forgot the water,’ he said before she had time to ask. ‘I’ll get some if I go out again.’

‘Were you thinking of going out again?’ she asked.

‘I can always do it tomorrow,’ he said.

She smiled at him. ‘That’s fine,’ she said. ‘Did you find anything?’

Evert Harting shook his head. He had stowed the gold chain in the car’s glove compartment. ‘Nothing but junk,’ he said. He placed the detector under the bench and plugged in the charger cable.

‘The pork chops have to be barbecued today,’ Ella told him. ‘They’ve been in the fridge since Thursday.’

‘Are you hungry?’

‘No, not yet.’

‘I can grill them later.’

Glancing at his watch, he checked the thermometer on the shady side of the verandah pillar. Half past two and twentyseven degrees Celsius.

‘There’s some cold squash in the fridge,’ Ella said.

With a nod, Evert Harting went inside and filled a tumbler. Beads of condensation formed on the glass as he poured. When he brought it outside, he noticed that Ella’s glass was empty.

‘In the house, eight letters,’ Ella said, scratching her chin with her pen. ‘Starts with I-N-T.’

Evert Harting took a mouthful of squash as he stood gazing out over the bay where roe deer came regularly in the evenings to lap up the water.

They had been married for thirty-eight years and now every day was the same, even out here at their cabin. Most things had already been said. From time to time, it struck him that crosswords were an attempt on Ella’s side to initiate some conversation. Sometimes she really knew the answer but asked him anyway because the solution might prompt something she wanted to talk about.

‘Inside,’ he suggested, without counting the letters.

‘That’s not in the house, though,’ Ella corrected him. ‘I first thought of interior, but that doesn’t fit.’

They had met at work. He was an administrator, and she had been in accounts. It was strange that crosswords were what she spent her time on after she retired, since she had worked with numbers all her life. Or maybe that was exactly why.

‘Did you speak to Kjell-Tore about the toilet?’ he asked.

‘Yes, he’ll take a look at it when he comes,’ Ella replied. They had bought the cabin beside Lake Farris following

the distribution of the estate after her parents had died, but it was still her brother who took care of the maintenance.

‘It’s no problem just using the outside toilet,’ Ella said. ‘After all, we had nothing but that before.’

Evert Harting took another mouthful of squash. KjellTore had also installed the incinerating toilet unit. It was only a couple of years old and had worked well until recently, but now the burner refused to ignite.

‘He was in Flensburg, on his way up,’ Ella added. ‘I asked him to buy some Jägermeister for you and those sausages that were so tasty. He’s got the fridge in the van, of course.’

‘Great.’

Kjell-Tore usually turned up in the middle of July. They spent a few days together before he and Ella borrowed his motorhome and drove north for a few days while Kjell-Tore was left alone at the cabin.

A bird with a wide wingspan flew over the treetops on the northern bank of the lake and soared out across the water. The wings flapped a couple of times before it disappeared behind the trees on the opposite side of the bay.

‘Internal,’ Evert suggested, downing the rest of the squash.

It seemed as if Ella did not know what he meant.

‘In-house,’ he clarified. ‘Internal.’

She looked down at the crossword, running the pen tentatively across the squares. ‘That fits,’ she said, a note of triumph in her voice.

This was the sort of thing he was good at. The ability to avoid getting locked into a particular mindset was something that had proved useful in his career. Always searching out alternative solutions and answers. Maybe that was one of the reasons why his thoughts had wandered far and wide when it came to the gold chain.

‘I’m going to sit inside for a while,’ he said. ‘In this heat?’

Without answering, Evert simply headed indoors to sit at the kitchen table where the laptop was kept. Ella followed him inside to fill her glass with squash from the fridge and opened a window to air the room.

He waited until he was alone before typing in two search words. Annika and missing.

The top results were from Norwegian online newspapers. Scrolling down, he selected instead an article from the Swedish Aftonbladet. A photograph of the missing fourteen-year-old Annika Bengt filled the right-hand side of the screen. His suspicions were immediately confirmed. She was wearing the same kind of necklace as the one he had found. The A for Annika lay on her suntanned skin, just below the hollow of her throat.

The article was almost four years old, and Annika had been missing for five days when it was published. The organized search had ended, and the police were left with no clues whatsoever.

The leader of the Swedish police investigation was pictured at Bovikstrand Campsite outside Gothenburg, where Annika had been staying with her parents when she disappeared. The picture was one of the last photos taken of her and had been used in every single report about the case, in Norwegian and Danish media outlets as well as Swedish ones. She looked a bit like the Annika in the Pippi Longstocking films, with a mop of dark hair and dark eyes that narrowed when she smiled.

There were also other photographs of her, which friends had published and that had spread even further. Several of these were from her schooldays in Vetlanda, but mostly they were of that last summer at Bovikstrand. In one of these she

was buried up to her neck in sand, so that only her head was visible. That was one of the very few in which the gold chain was nowhere to be seen.

He clicked away from the images and located a more recent article, from the previous summer. The missing person case remained a mystery. Every trace ended when she left her group of friends on the beach just before midnight. A misunderstanding had led to her not being missed until the next morning. She had been supposed to spend the night in a caravan with two of her friends but had gone to her parents’ van to fetch something. Her friends thought she had changed her mind and stayed there, while her parents thought she was fast asleep, safe and sound, at the opposite end of the campsite. In the article written three years later, no reservations were expressed about her disappearance being due to anything other than a criminal act.

Out on the verandah, Ella switched on the radio, choosing a station that broadcast music and traffic reports.

Evert returned to the search page and combined Annika Bengt with the words gold necklace. The only results were articles in which the chain with the letter A was mentioned in descriptions of her, nothing about where the piece of jewellery had been bought or where it came from.

The initial necklace was what they called it. There were various types to be had. The one he had found was what seemed to be styled a chain with side-hanging letter in yellow gold. He found a Norwegian online store that sold an identical type of chain to the one Annika had owned. There it was described as an asymmetrical design of personal jewellery and cost less than he had anticipated. Just under 3,000 kroner for the chain and pendant.

Thousands of satisfied customers bragged the online store. He

tried to make an estimate of how many necklaces they might be talking about. Half the Norwegian population were female. He could not envisage Ella with a necklace like that – she was too old for it. He rounded the number down to exclude both the oldest and very youngest prospective customers. And there were twenty-nine letters in the Norwegian alphabet, but not all of these were equally widespread in use. If he divided two million by twenty, he ended up with a hundred thousand potential purchasers. However, he could not imagine that more than one in a hundred had bought the very same necklace. It was a bit like walking through the streets – you would probably pass more than a hundred women before you would come across someone wearing identical clothes to any of the previous passers-by.

One in a hundred.

A thousand initial necklaces sold in Norway. Maybe double that in Sweden.

How many could have lost their chains?

The likelihood began to shrink.

Slowly, he closed the laptop lid. It was mere speculation, going nowhere. Anyway, he wasn’t sure this was something he should try to pursue any further.

All of a sudden Ella was there in the room. Time had passed quickly while he had been busy in front of the laptop. Nearly two hours had gone by.

‘I think there’s some potato salad left, isn’t there?’ she said, opening the fridge door.

He rose to his feet. ‘I’ll go and light the barbecue,’ he said, but he lingered for a moment, lost in thought.

What he should really do was throw the necklace back where it came from, into even deeper waters.

There was no shade down on the crazed lake-bed. Wisting had scrambled back up to Hammer to follow the crime scene technicians’ work from above. A huddle of crows bickered in the background.

Wisting leaned against the low wooden fence. The case of the young man who had vanished with his motorbike had certainly crossed his mind from time to time. It had hung over him as an unsolved mystery. He no longer spent time dwelling on what might have happened, but it had become an enduring blank. Nevertheless, the boy’s discovery now brought him no satisfaction. Quite the opposite, in fact, since Morten Wendel could no longer be held accountable for what he had done.

The technicians worked methodically on the site below. Before they started on anything else, they had taken overview photographs and measured distances. The rear wheel of the motorbike was six metres and thirteen centimetres from shore, on what would be a depth of around five metres at normal water levels.

The young summer recruit who had greeted Wisting earlier at the pile of debris was watching carefully.

‘Could I ask you something?’ he ventured tentatively after they had been standing in silence for a while.

Wisting responded with a nod of the head.

‘How do you actually go about becoming a detective?’ he asked.

The man by Wisting’s side was somewhere in his early

twenties. He appeared to have a family background from Pakistan or somewhere near there. His hair was thick and dark and his beard neatly trimmed, making him look older than he really was.

‘What’s your name?’ Wisting asked.

‘Daniyal.’

When he held out his hand and introduced himself, Wisting shook it warmly.

‘Daniyal Rana,’ the young officer elaborated. Wisting recognized the name from reports he had read.

‘So that’s who you are,’ Wisting said, nodding. ‘You were out at the break-in at the warehouse in Hegdal last week, weren’t you?’

‘That’s right. Have you made any progress on that?’

Wisting shook his head. ‘Were you thinking of becoming a detective, then?’ he asked.

‘I think it seems an interesting prospect,’ Rana admitted. A call came in over the police radio and one of the other officers answered. The controller at HQ wanted them out on the E18 to assist a motorcycle patrol in following an unsteady vehicle that was refusing to stop. The two other officers rushed to their car, but Daniyal Rana remained behind.

‘There are a number of routes leading to a job as an investigator,’ Wisting said, responding to his earlier question. ‘But the most important one is probably to show a keen interest.’

That was how he himself had ended up as a detective. The first few years after Police College he had spent on patrol duty but while many of his other colleagues had simply written reports about what they’d experienced at a crime scene or on an assignment, Wisting had also enjoyed following these cases up. He had made his own enquiries and provided extra information in various instances, above and beyond what was

expected of him. This had been noticed and meant that the doors to the criminal investigation department had opened wide for him. Nowadays the situation was different. Formal qualifications counted for more than personal qualities.

‘What do you look for when you take someone on?’

‘Several things,’ Wisting said. ‘Wide experience as a general basis, of course, but also qualifications that are difficult to measure. Aspects such as the ability to cooperate and the skill to spot connections between different pieces of information.’

They continued to stand in silence, watching the painstaking work of the crime scene technicians. All the fragments of bone were collected in a large cardboard box, while clothing was sorted, marked and packed in paper bags.

‘Did he simply disappear?’ Daniyal Rana asked.

‘It’s a mystery, to be honest,’ Hammer confirmed.

‘He was supposed to have been alone at home for a few hours that evening,’ Wisting explained. ‘When his parents returned, he and his motorbike were gone. They assumed he’d just decided to drive around, but when he didn’t turn up, they feared he’d had an accident. First of all, they phoned the emergency doctor and the hospital, then they called the police. No one knew anything.’

‘Was there no trace of him at all?’ the summer recruit asked.

‘Nothing,’ Hammer concluded, lifting the bottle of water to his mouth.

‘But surely he was reported missing?’ the young man continued. ‘Someone must have seen him?’

Nils Hammer screwed the lid back on the bottle.

‘We publicized pictures, both of him and the motorbike, but that didn’t lead to anything specific,’ he replied.

‘What about CCTV at petrol stations and suchlike?’ Daniyal Rana insisted.

‘We checked everything like that,’ Wisting explained. ‘It yielded nothing.’

‘What about neighbours, then? Did nobody see or hear him start up and drive off?’

‘It seemed as if he’d sneaked out and away,’ Hammer replied. ‘Now we know why.’

He pointed in the direction of the discovery site where the technicians were finishing off. One of them was wiping his forehead with a rag.

‘Why did he take his own life?’ Rana asked.

Wisting glanced across at Hammer to see if he wanted to tell the story. Before either of them managed to say anything, however, they heard the loud approach of a heavy vehicle. A recovery truck crawled towards them along the narrow gravel track, pushing twigs and branches aside as it travelled. The driver leaned out when he reached them. A young man in a grey T-shirt with patches of dried sweat along the neckband. Wisting stepped forward and explained what kind of assistance they required. The driver jumped out and looked down at the scene on the shore before reversing to the wooden fence and taking up position.

The technicians gathered their evidence containers at the foot of the rock face and transferred them into a lifting bag. The man from the recovery truck manoeuvred the crane arm out over the edge and fired out a wire with a hook on the end down to them. In no time, it had all been hauled up.

The helmet, seemingly still with human tissue and hair inside, was dropped into a large plastic bag.

Wisting opened the package containing the leather jacket and lifted it out. When he felt the material, he realized there was something tucked into the inside pocket, so he handed it to Daniyal Rana.

‘See what you can find out,’ he said.

Following Wisting’s example, Daniyal Rana checked the jacket pocket and took out a wallet. Stiff and brittle, the seams had frayed in a few places and the leather cracked when he unfolded it.

There were sections for banknotes and cards as well as a coin purse with a zip. In the top card pocket, he found a pink plastic driving licence. Rana fished it out and glanced at it before handing it to Wisting.

The text and image were still clearly visible. Morten Wendel, driving licence class A1.

The very same day he had obtained his licence, he had bought a light motorbike. Only three months later, he had disappeared along with the bike.

Daniyal Rana checked the rest of the wallet. It contained a plastic bankcard and a library card, both filled out in the same name. In the section for banknotes, he found a 50-kroner note folded with some papers that had crumbled away. The coin purse contained 12 kroner and a small key.

Wisting kept the driving licence while Daniyal Rana returned the wallet to the paper bag with the jacket.

‘Have you been in touch with his parents recently?’ Hammer asked.

‘Not since last summer,’ Wisting told him.

The revs on the recovery truck increased as the crane arm shot out towards the motorbike. The technicians had attached lifting straps, and it was slowly hauled out of the bed of solidified sludge. The front mudguard hung crookedly, and clumps of earth loosened and dropped off. One of the technicians had tied a rope to the rear wheel and steered it towards the recovery truck. There was a screech of scraping metal when it was laid flat on the truck bed.

‘Cover it with a tarpaulin,’ Wisting instructed. ‘I haven’t informed the next of kin yet.’

He turned to go back to his car.

‘What about the safe?’ Daniyal Rana asked.

Wisting retraced his footsteps to the rocky edge and peered down at the grey metal cabinet, jammed beneath barbed wire and other scrap metal with the door turned down.

‘Take it with you,’ he said. ‘See if you can find out where it came from.’

The entrance was located on the shady side of the modest house. Boisterous children in the neighbouring garden were playing on a trampoline, their gleeful shrieks carrying on the still air.

Wisting pressed the doorbell but could not hear any sound from inside.

To the left of the door, three tubs were overflowing with lilac flowers. A wet patch beside them suggested they had just been watered.

No one arrived to open the door. He tried the bell again and knocked on the door a couple of times. Still no reaction. It occurred to him that the occupants might be out in the garden on the other side of the house.

The gravel crunched under his feet after he descended the steps. Before he rounded the corner of the gable wall, a small delivery truck drew to a halt out in the street. The engine rumbled and idled for a few seconds before falling silent.

Wisting turned and headed in that direction instead. Allan Broch-Hansen was now standing beside the vehicle, leafing through a sheaf of papers. He was still employed in goods transportation and the company name was printed on both his T-shirt and the side panel of the truck. The vehicle looked new, but Broch-Hansen had grown older in the time since they had last talked. Gaunt and grey-haired. Clearly startled to see Wisting, he dropped a sheet of paper when he caught sight of him.

‘Anything wrong?’ he asked.

Wisting shook his head. ‘Nothing to worry about,’ he replied.

Allan Broch-Hansen shot a glance in the direction of the house. ‘Have you been speaking to Irene?’ he asked.

‘I tried the doorbell,’ Wisting explained.

The high jinks in the neighbouring garden seemed to have developed into a squabble. Broch-Hansen bent down and picked up the paper he had dropped.

‘The doorbell’s disconnected.’ He studied Wisting’s face as he said this. ‘Are you here because of Adine?’

‘Partly,’ Wisting answered. ‘It’s to do with Morten Wendel.’

Broch-Hansen blinked, and his face contorted. ‘Have you found him?’ he asked.

‘We think so,’ Wisting replied, waving his hand in the direction of the house. ‘Let’s do this inside, unless you’d prefer to tell Irene yourself.’

‘No,’ Broch-Hansen was quick to demur. ‘Come on in.’

He strode ahead to the front door, his back stooped.

Halfway to the house, he stopped and turned to face Wisting.

‘Adine’s coming home on Wednesday,’ he said. ‘One week’s leave of absence. She’s at a centre in Hurum that treats both drug dependency and psychological problems.’

‘Is it going well?’

Broch-Hansen shrugged. ‘It’s too early to tell,’ he answered.

Unlocking the door, he called out his wife’s name. She appeared at the end of the hallway, looking past her husband to meet Wisting’s eye.

‘Everything’s fine with Adine,’ her husband assured her. ‘They’ve found the Wendel lad.’

Irene Broch-Hansen touched her chest nervously. ‘He’s not alive, is he?’ she asked.

Her husband looked at Wisting. ‘He’s come to tell us,’ he replied, taking off his shoes.

Wisting did the same. His shoes were grey with dust from the parched lake-bed and his trousers were badly stained.

They moved into the living room, where sheer curtains fluttered in the doorway that led out to the terrace. Irene Broch-Hansen shut the patio door.

‘We can sit here,’ she said, settling on the settee.

Her husband sat down beside her and Wisting chose an armchair on the opposite side of the coffee table.

‘He’s dead,’ he said. ‘He has been ever since that time.’

The couple on the settee briefly exchanged looks. A photo of their daughter from her high-school days was displayed on the wall behind them. She had been seventeen that summer, in the class above Morten Wendel. They had been neighbours at that time, and both had been left alone at home for a few days while their parents were absent. Adine BrochHansen had been sunbathing out on the terrace when Morten Wendel had slipped through a gap in the hedge and asked her for help. The family’s pet dog had started breathing oddly and he was afraid it was choking.

Adine raced with him back to his house.

‘He’s upstairs in my room,’ he had told her, running up the staircase to the first floor.

When they came across the dog, it had seemed perfectly healthy – just glad not to be shut inside any longer. They concluded that something must have got stuck in its throat and had dislodged by itself. Later, Adine felt it must all have been pre-planned.

‘Don’t go,’ Morten Wendel had pleaded, blocking the bedroom door. ‘You’re so gorgeous.’

She had laughed at him and wriggled away when he started

touching her. She had managed to escape from the bedroom, but at the foot of the stairs he had caught up with her. He hadn’t succeeded in dragging her upstairs again but had attacked and raped her in the living room. He had held her captive for an hour, gagged and taped tightly to the furniture. She broke free when he went to the bathroom, and had darted out into the street, stark naked.

‘Where did you find him?’ Allan Broch-Hansen asked.

Wisting explained about the motorbike and the spot where it and the body had been found out at Lake Farris.

When Irene Broch-Hansen began to sob, Wisting appreciated it was from sheer relief.

‘Sorry,’ she said. ‘It’s been difficult, not knowing what had become of him.’ She wiped her eyes with her fingers. ‘Mostly for Adine, of course, who didn’t know if he would come back and try it again.’

‘He took his own life, then?’ Allan Broch-Hansen asked.

‘It all points to that,’ Wisting said, nodding.

Morten Wendel had been arrested a few hours after Adine had escaped. He had his own version of what had occurred, claiming that Adine had approached him, dressed in only a bikini, and had been the one to take the initiative. Everything had been consensual. The evidence at the crime scene told a different story. After a fortnight in custody, he had nevertheless been released, partly because he was so young. Six days later, he had vanished.

Wisting looked across at Allan. ‘You said Adine’s coming home in two days’ time?’ he asked.

‘On Wednesday, yes,’ Allan Broch-Hansen confirmed.

‘She should probably be told before that,’ Wisting said. ‘The discovery’s bound to be a major news story.’

‘Maybe she could come home a day early?’ There was a

hopeful note in Irene’s voice as she suggested this. ‘We can’t tell her about this over the phone, but if I speak to the person in charge there, we could probably pick her up tomorrow. They know what she’s been through and what she’s struggling with.’

‘I’m driving all day tomorrow, though,’ Allan said.

‘That could wait till the next day, couldn’t it?’ Irene said. ‘We were planning to go on Wednesday, after all.’

Allan Broch-Hansen nodded. ‘That’s what we’ll do, then,’ he agreed.

An uneasy silence lingered around the table. Wisting had been prepared for an angrier reaction. Irene Broch-Hansen in particular had placed all the blame for Adine’s problems on the sexual assault eight years earlier. That Morten Wendel had simply disappeared and never been held to account made everything even more difficult. Prior to the rape, Adine had been a lively girl, but afterwards she had withdrawn from social contact. Suffering from anxiety and depression, there were concerns about potential suicide risk and eventually abuse of alcohol and other narcotics. Now that the perpetrator had been found dead, the situation had changed. The uncertainty was gone, and the attack would be easier to cope with.

Wisting prepared to leave. ‘I can call in again once she’s here,’ he said. ‘She’s sure to have a lot of questions.’

‘We’d welcome that.’ It was Irene who had answered.

Wisting got to his feet, as did Allan Broch-Hansen.

‘Have Reidar and Gunn Hilde been told?’ he asked.

Irene frowned, as if it were unreasonable to spare a thought for Morten Wendel’s parents.

‘Not yet,’ Wisting replied. ‘I’m driving over to see them next.’

‘You don’t need to tell them you’ve been here,’ Irene said. With a brief nod of the head, Wisting allowed Allan BrochHansen to accompany him to the door.

The first time Wisting had been tasked with conveying bad news, it had affected him more than he had anticipated. It concerned a mother who had lost her son in a drowning accident. Unable to stay on her feet, she had collapsed on the floor, completely distraught. She had lain there, twisting and turning in her anguish over the loss, and there was nothing Wisting could do to ease her distress.

There was no easy way of breaking the news of a death. Words were useless, no matter how compassionately expressed. But exactly because this was a difficult assignment, it was something Wisting was never willing to delegate to others.

Gunn Hilde Wendel stood with the garden hose in her hands, watering a flower bed. Barefoot, she was wearing a skirt and camisole and had a straw hat on her head. It took a few minutes for her to realize she was no longer alone. Wisting had to walk out on to the brown, scorched grass and move right up beside her. The jet of water swung out across the dry lawn when she spotted him.

Wisting nodded and gave her a reassuring look. The water collected in a small puddle before she managed to turn off the tap.

‘It’s been a long time,’ she said, wiping her hands on her skirt. ‘I thought you’d have retired by now.’

‘They changed the pension rules,’ Wisting replied with a smile. ‘But I’ve come with bad news, I’m afraid.’

‘About Morten?’

‘Yes.’ Wisting looked around. ‘Is Reidar at home too?’

Gunn Hilde pointed at the door.

‘Inside,’ she said, and walked on ahead of him.

The temperature indoors was pleasant. Reidar Wendel was seated at a circular coffee table, a brown mongrel dog at his feet. He put down his mobile phone and stood up when he noticed them. On the wall behind him, an air-conditioning unit purred as it lowered the room temperature.

‘It’s about Morten,’ his wife said.

‘Have you found him?’

‘A few hours ago,’ Wisting answered.

They stood for a minute or two, gazing at one another, before Reidar Wendel indicated they should sit down. The dog sprang up when Wisting drew out a chair. It padded off and lay down further across the floor, close to the spot where Adine Broch-Hansen had been raped.

Wisting surveyed the room again. The fixtures and fittings were more or less the same as in the crime scene photographs. The massive dining table was in the same place, where the girl who had lived next door had been taped tightly to the table-legs.

He returned to the business at hand and took out his notebook to support the timings and other essential facts.

‘He was found with his motorbike at the bottom of Lake Farris,’ he began, before correcting himself: ‘What used to be the bottom. The water has pulled back almost five metres because of the drought.’

The couple both nodded.

‘It looks as if he went awry at the bend somehow,’ Wisting added. ‘A track on the western side, near Vassvik, very little used. A spot called the Yeller.’

‘Didn’t you look there?’ Gunn Hilde asked, her voice hoarse.

‘I’d need to go back to the case paperwork to check, but there’s nothing to suggest we did,’ Wisting replied.

‘Why not?’

‘We searched along all the roads and in the ditches, but we would have to have used divers to find him there.’

He left a momentary pause, forming the next sentence in his head before he went on to break the news.

‘It does look as if he launched himself out into the water deliberately.’

The words sounded heartless, no matter how carefully and considerately he expressed himself.

Gunn Hilde Wendel’s voice was trembling. ‘How can you say anything of the kind?’ she asked.

‘There are certain details I’ve seen before, in similar cases,’ Wisting answered calmly. ‘One hand was firmly fixed to the handlebar, as if he had made up his mind. As if he had come to a decision.’

The woman facing him swallowed hard, her eyes shining with tears. Her husband put his hand on hers, but she pulled away.

‘You drove him to it,’ she said. ‘Accusing him of all sorts of things. Trying to put him in prison.’

The dog lifted its head but remained sprawled on the floor.

‘It was that girl you should’ve arrested, coming out with all those false accusations,’ Gunn Hilde went on. ‘She was already using drugs at that time. She was mad, without a doubt. Look at her now – in and out of psychiatric care. She even tried to set fire to our house before she burned down theirs.’

Wisting had heard this spiel before and was prepared for this reaction. He had spared the parents certain aspects of the case. The crime scene technicians had examined their son’s room and found semen stains on the wall at the

window overlooking the neighbours’ garden. They had concluded that he had stood there masturbating while watching Adine. On his phone, they had found photos of her, going back almost a year in time, some of them taken through the windows. In one of these, she had been indoors, walking naked between the bathroom and her bedroom. Telling Gunn Hilde Wendel about this evidence of obsession would probably not persuade her to think any differently about her son, but all the same it was not something Wisting was keen to bring up.

‘I’m sorry,’ he said.

Gunn Hilde Wendel sat back firmly in her seat, in a clear demonstration of her rejection of his sentiment. Her husband put his hand on her arm.

Wisting was aware that doubt and uncertainty would surface in them both and he was unwilling to leave them in such a situation, so he set out the facts he had in his possession.

‘The body is being sent for forensic examination,’ he told them. ‘We already have his DNA profile. In the course of the next forty-eight hours, we’ll have final confirmation.’

‘So you’re not entirely sure it is him?’ Reidar Wendel asked.

‘It is his motorbike, his helmet and his clothing,’ Wisting replied, anxious not to leave any doubt about it. ‘We found his wallet with his driving licence. The examination at the National University Hospital is really just a formality.’

Reidar Wendel nodded.

‘I can contact an undertaker to take care of the practical details afterwards,’ Wisting continued.

‘Gabrielsen,’ Gunn Hilde interjected. ‘We used them when Mum died. Fortunately she was spared all this.’

Wisting was familiar with the firm but wrote it down all the same. Mostly for the sake of appearances.

‘If you like, I can take you out to the discovery site,’ he said. ‘Not today, but any other time that suits you.’

Reidar Wendel leaned forward slightly. ‘Where did you say it was?’ he asked.

‘Near Vassvik,’ Wisting said, launching into further clarification.

‘I know where that is,’ Reidar Wendel interrupted him. ‘I just don’t understand how Morten ended up getting lost in that neck of the woods, away on the other side of town.’

‘He wasn’t himself, though,’ his wife pointed out.

Wisting did not have any better answer to offer.

‘There are a few things you should prepare yourselves for,’ he said. ‘The media are certain to show interest in all this.’

Gunn Hilde Wendel’s lips tightened. ‘Do they have to know about it?’ she asked.

The dog struggled up from its spot on the floor and stared across the room at them. Wisting shifted in his seat. It was difficult to find a humane way of explaining why the discovery of a body on the bed of a dried-up lake would spark interest in both journalists and readers.

‘Many people are already involved,’ he said. ‘We can’t prevent the farmer who alerted us from passing on the information to other folk. It’s an unusual case. It’s bound to get out.’

Gunn Hilde’s tense lip began to tremble. ‘They wrote so much nasty stuff at the time it happened,’ she said.

‘They’re going to write much of the same stuff again, I’m afraid,’ Wisting told her.

‘But he was never found guilty of anything,’ Gunn Hilde said. ‘He’s innocent. Can’t they write that?’

Wisting composed his face into sympathetic lines. Naïve questions from close relatives were always difficult to answer.