The Wax Child

By

By

Olga Ravn

Translated from Danish by Martin

Aitken

UK | USA | Canada | Ireland | Australia India | New Zealand | South Africa

Viking is part of the Penguin Random House group of companies whose addresses can be found at global.penguinrandomhouse.com

Penguin Random House UK , One Embassy Gardens, 8 Viaduct Gardens, London SW 11 7BW penguin.co.uk

First published as Voksbarnet in Denmark by Gyldendal 2023

First published in English in the United States by New Directions 2025

First published in Great Britain by Viking 2025 001

Copyright © Olga Ravn and Gyldendal, 2023, 2025

Translation copyright © Martin Aitken, 2025

The moral right of the copyright holders has been asserted Penguin Random House values and supports copyright. Copyright fuels creativity, encourages diverse voices, promotes freedom of expression and supports a vibrant culture. Thank you for purchasing an authorized edition of this book and for respecting intellectual property laws by not reproducing, scanning or distributing any part of it by any means without permission. You are supporting authors and enabling Penguin Random House to continue to publish books for everyone. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner for the purpose of training artificial intelligence technologies or systems. In accordance with Article 4(3) of the DSM Directive 2019/790, Penguin Random House expressly reserves this work from the text and data mining exception

Set in 11.5/15pt Kepler Std Typeset by Six Red Marbles UK, Thetford, Norfolk

Printed and bound in Great Britain by Clays Ltd, Elcograf S.p.A.

The authorized representative in the EEA is Penguin Random House Ireland, Morrison Chambers, 32 Nassau Street, Dublin D02 YH68

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

ISBN : 978–0–241–75274–6

Penguin Random House is committed to a sustainable future for our business, our readers and our planet. This book is made from Forest Stewardship Council® certified paper.

I am a child shaped in beeswax. I am made like a doll the size of a human forearm. They have given me hair and fingernail parings from the person who is to suffer. I was borne by my mistress for forty weeks under her right arm as if I was a proper child, and my wax was softened by her warmth. After this time, she took me to a pastor; it was night, the church was dark and still, and he christened me, the wax child. I was an instrument. This was at Nakkebølle Manor, in southern Funen. My wax mouth cannot be opened.

I know the humans well, though they don’t know me. I am an image, in the absence of a child. I have this bottomless, shaft-like longing for the woman who made me, whose name was Christenze Kruckow. Her sweat smelled so tangy, of . . . cloves, perhaps. There were carriages and horses and soldiers. There was marjoram and thyme and rose hip. There were ships that journeyed far across the sea to lay claim to territory. There were ships filled with living bodies in the darkness of their holds. There was a scream. And a refinement. The finest pattern cast by the sun through the grille of the confessional. And through the towns religious processions went, and chorused wonderful song. The year passed, and the years passed. And I was a wax child. I did not age. I lay in the ground and saw it all. Insects and worms approached, to retreat on sensing my poison. I saw the rising of realms, the founding of states, the centralizations of power. I saw the clouds hasten by. I saw the great black tongues of oil advance as the fern from the soil

puts out its feelers. I saw hands be raised and clench into fists. I saw knives gleam, children play. I saw steam locomotives, the smallest particle split and exploded. I lay in the ground. And from there, at certain times of the month, I could observe the brilliant moon. No one was carrying me any more.

No one listens to a thing I say. Although I speak all the time. I am a lump of beeswax shaped in the image of a newborn child. I am no more than what may melt and stiffen again in the night. No one comes to me here. I lie and speak with my eyes. My family no longer exists, or rather: my kind of family, a very large one, no longer exists. And still I speak. A steady stream of words that slip from me without cessation, and I too am inclined to think it is often an embarrassment. But I cannot stop it, my mouth will not desist, though I don’t know how the words get out – I have no larynx, no vocal band, no tongue. But who does it interest? Children should be seen and not heard, as they say. But then I’ve already told you, I am not a child, only something that looks like one. Something that longs to be one. I’m an internal event. By nature unfinished, or condemned to anticipation, awaiting my mistress, who since she is dead comes no more. Now I speak again to the soil that covers my face. Now I speak again to the semi-carbonized, the soon-composted apple someone tossed, in the place where I lay.

There was a night when I was still lying in the bed of my mistress. Yes, I remember it. She wakes with a start, sits up, looks out. Others, in the surrounding houses of the town, wake in the same manner. They don’t know why. They are possessed by such a strange feeling. I observe them. I hear their thoughts. There’s something not right, something awry. The salty air – as if the sea has flooded into their rooms. They don’t know it yet, but still they sense it. The Earth turns slowly into modernity. And in the space of an imperceptible moment, the old world has succumbed conclusively to the new.

Whenever a woman nearby to me was about to give birth, I would lie in the ground and feel almost exalted, as if the arrival of every child was a chance for me to find a place in the world, for my soul to dart into one of those newborn infants, my mouth to open and expel its very first cry. But I remained there. Whenever a woman nearby was about to give birth, a messenger would make haste to the midwife and whoever else the pregnant woman had asked to help. All let go then of whatever was in their hands, and came as quickly as they could. Some in the night, others in the frost of morning; with fleetness of foot they came, and barely inside the door would take upon them the housekeeping. They would introduce a new and temporary regime, which meant that those who normally frequented the house would have to find new places to stay. I saw these women form a ring around the one in labour and lead her to the bath house. I saw them douse the burning-hot rocks with water; I saw the steam and the scalding herbs. They undressed the birthing woman, and the naked one was Anne Bille, the young mistress of Nakkebølle. And by the stone wall of the bath house they had placed me in the ground, and I lay and listened there as Anne Bille gave birth to the first of her children. And the midwife came then with her long strides, known for her skill of directing into another the pains of the woman in labour, and it would be said then that she who received the pain of the travailing woman held the skin girdle. And the women of the household took turns to

hold the skin girdle on Anne Bille’s behalf. And my own mistress, Christenze, could hold it the longest, and it was said then that this was because she had never lain with a man and therefore possessed a virgin’s strength. And later in the morning, Eiler, Anne’s husband, returned to the manor, and he stood and kicked at the gravel outside the stone bath house, and said, I heard it myself, to the midwife, that this was a dreadful racket his wife was making in there, and how much could such a thing hurt, and I saw then the midwife’s eyes narrow, and without him understanding what was happening she gave him the skin girdle to hold and immediately he fell to the ground and cried, O, help me, I feel such terrible pain, and all the women then laughed, Christenze and Ousse and the others too, they shrieked with laughter, and Ousse said: There, she certainly gave you the skin girdle to hold, that you may learn what your woman endures to bring your offspring to the world.

But every time Anne Bille gave birth, no matter who held the skin girdle, the child died in the days that followed. I heard one of them scream as if death had appeared before it, and soon it expired at Anne Bille’s breast, not a single night old. Others were blue and lifeless, too small at birth to survive. Then one day my mistress said to Anne: Anne, I have noticed you are rather unwell. Come to me and I will give you sheep’s milk. You have borne four children, and none is alive. Let me help you to keep the next. And my mistress went and milked a sheep. In the kitchen, she took up some of the milk on a spoon and as she heard Anne approach the door she picked from her pocket, with two fingers, a spider and placed it in the milk so that the attercoppe was concealed in it. She stood with the spoon ready when Anne came in, and obediently Anne went to the spoon, put the spoon without a word into her mouth and swallowed the milk and the spider unknowingly in one gulp, and went on her way. At this time she was eight months pregnant and was full of hope and anxiety, and would accept any advice. And when the child came it was alive and well formed, with the correct number of toes and fingers, a girl with chubby cheeks, and Anne sat up in her maternity bed and was radiant, a sigh of relief went out, not only over Nakkebølle, but over all of southern Funen – at last a healthy, bouncing baby was given to Anne, and she swaddled the child. But the next morning the newborn lay cold in her cot. It was Ousse who discovered it, and Anne turned away on to her side in the bed

with her back to the child and said nothing. I shall let her be, so you can say goodbye, Ousse said, but Anne did not reply, and Ousse went then to the kitchen, for she was a servant girl, to share the solemn news. And there she sat as yet when Anne came bounding with the child. It lives, it lives! she cried, and held the child out for them to see, and Ousse and Anne bent over the newborn and it was true, the face, with its closed eyes, widened and crumpled, the mouth shaped the smallest of movements, and the lips parted slowly as if to expel a tentative sound. There, you see, Ousse! Anne cried. She lives! And the child’s mouth opened and out came not a sound but a spider; and they stood then, as if they were petrified, and gaped at the infant as the spider scuttled across her face and jumped away, and Anne screamed and let go of the child, whose body fell to the stone floor.

And thus some twelve years passed, and before Anne was thirty-two she had given birth to and lost fifteen infants. And with every child that died she became meaner and more bad-tempered, unhappy, abusive, and she would scratch the faces of her servant girls and at dinner would stab her own hand with forks and laugh out loud, and she cast her gaze at Christenze, my mistress, then still younger, though not young, perhaps thirty-six years old, but unmarried, and fond of riding, often at dinner she would still be in riding boots, and Anne scowled then at this ruddy-cheeked, unwed noblewoman and hissed between her teeth: You, ’tis you, you are a witch. But Christenze merely laughed and rolled her eyes and drank more wine, and there were times when Christenze, my mistress, would think it better if she had been born a man, when still a child the thought had struck her that she possessed that very restlessness and strength; and if ever the chance came her way to gallantly step in and perhaps shield in her arms a servant girl who happened for instance to be frightened by a fierce dog at the moat, then the rest of her day would be spent pondering what Christenze understood were manly values, protecting and shielding, riding and fencing. So Christenze had never ingratiated herself to any potential husband, had never married, never wanted to, never felt an urge for mayor or king’s lieutenant, nor any marital bed, had shunned all notion of prenuptial agreement, bridal veil and marriage chest, preferring to horse-ride on her own and drink red wine and read letters well into

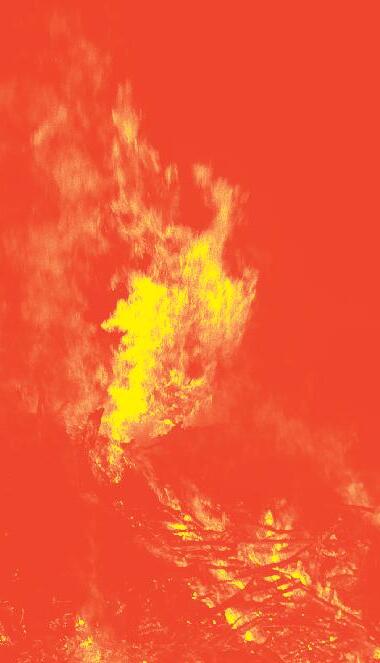

the night; the Beheaded Virgin is what she later would call herself – after death, of course – her head, separated from her body, told me so from within the flames, when they tossed both it and the body, headless, on to the fire, Farewell my child, the lips sighed on seeing me on the arm of another in front of the bonfire, and had I been able to cry my eyes would then have cried, and had my mouth been able to shape a word it would then have done so, but I saw her detached head say: Farewell, my child, farewell from the Beheaded Virgin. However, all this was a long time later. I am anticipating events. Christenze is still alive. It is night, night over southern Funen. She is asleep in her room. She has put me in the basket. The still being of night entwines itself in the treetops. I think I love her with that part of me that is never illuminated.

Whoever wishes to know if a sick person will live or die shall take a gem-stone that is known by the name of emerald and place it then upon a person who is gravely ill. If he is to die, the stone will shatter. It should be placed upon the heart.

Or count how many days from the beginning of his illness and take then a herb having as many leaves as the number of days, and hang it upon the sick person.

Or take the milk of a woman giving breast to a boy and put it in the sick one’s urine. Stir, and if the milk runs together, he will become well again.

Or take a crumb of bread and stroke with it the temples of the sick one, then give it to a dog to eat.

Or take a piece of flesh and rub the soles of the sick one’s feet with it, and throw then the flesh to a dog. If the dog devours it, this is a sign the sick one will become well again; if the dog does not, then he will die.

A man entered a town hall with an anticipation of total obedience. As a child he was offered the choice between an apple and a knife. He learned how to slaughter a pig. The man I see has access to many castles and manors. He never lives in the same place for any length of time. He is always on his way, administering his realm. He is Christian IV, king of all Denmark and Norway. Mail is read to him. He smells of hidden blood. She chose the night in which to do it. She lit the fire and began to heat up the water. She saw a shooting star from the window. There was a draught. The beeswax in the pot started melting from the sides. It smelled of honey. When she stirred the pot in order to turn the lumps of wax, it was as if something that at first occupied the darkness surrounding the manor house now had entered the kitchen. She could feel its gaze upon her, a beast such as a wolf, or an elf-creature perhaps – it bit her on the neck. She put her hand to the bite. Two eyes hung before her in the air and looked at her a moment until falling to the ground with a chiming sound as made by flintstones. She searched herself for strength, a love of herself. Tightly she wound a strip of fabric around the mould, and stirred the wax to make sure it was melted. She rubbed some human hair into a knot between her fingers and dropped it into the mould before carefully pouring in the beeswax. The beeswax ran and settled, as inchmeal she poured. And during this procedure her first memory suddenly comes to mind, a recollection she has held inside her, like a lucky pebble