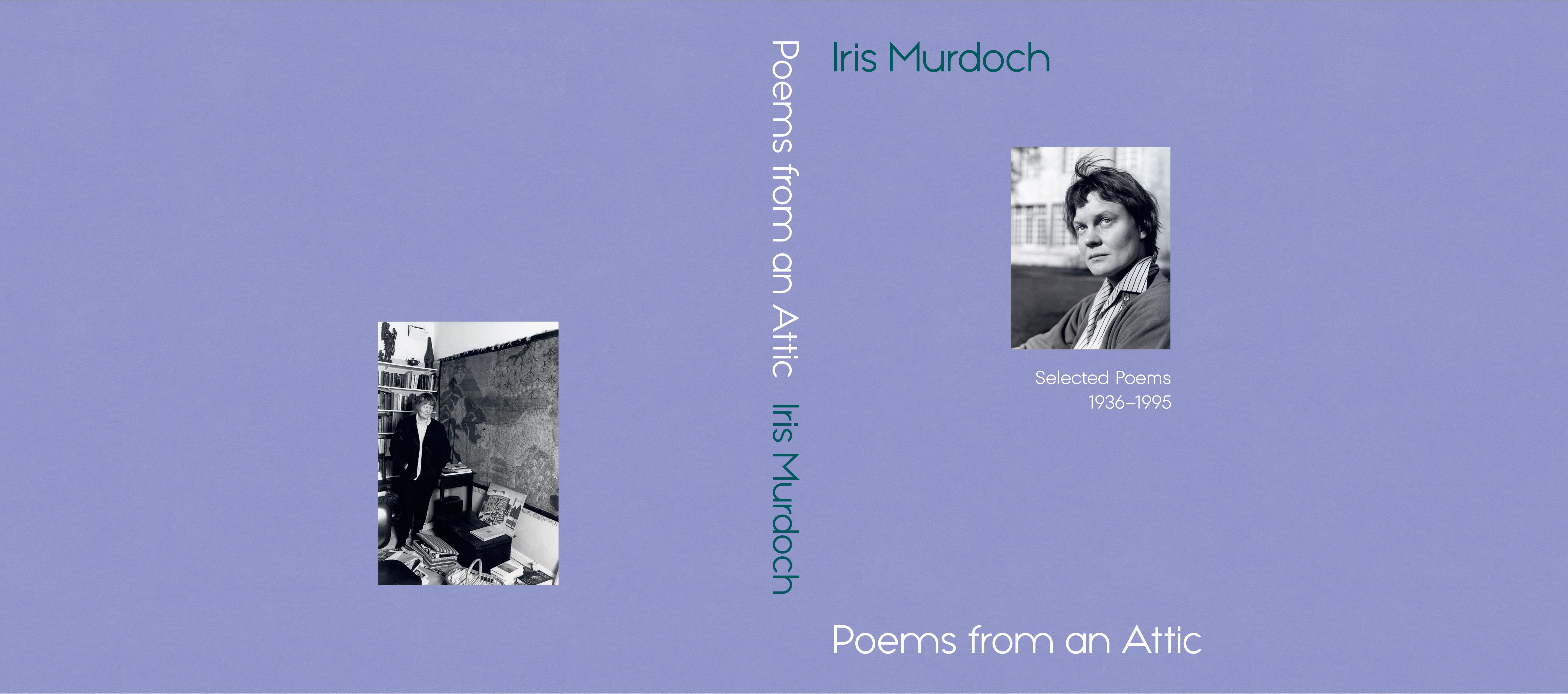

POEMS FROM AN ATTIC

Selected Poems, 1936–1995

Iris Murdoch

Edited by Anne Rowe, Miles Leeson, Rachel Hirschler and Frances White

With an introduction by Sarah Hall

Chatto & Windus

london

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

Chatto & Windus, an imprint of Vintage, is part of the Penguin Random House group of companies

Vintage, Penguin Random House UK , One Embassy Gardens, 8 Viaduct Gardens, London SW11 7BW

penguin.co.uk/vintage global.penguinrandomhouse.com

First published by Chatto & Windus in 2025

Copyright © Kingston University 2025

‘Motorist and Dead Bird’ and ‘Edible Fungi’ © the estate of Iris Murdoch 2025 Introduction © Sarah Hall 2025 Iris Murdoch: Poet © Anne Rowe, Miles Leeson, Rachel Hirschler and Frances White 2025

The moral right of the copyright holders has been asserted

Penguin Random House values and supports copyright. Copyright fuels creativity, encourages diverse voices, promotes freedom of expression and supports a vibrant culture. Thank you for purchasing an authorised edition of this book and for respecting intellectual property laws by not reproducing, scanning or distributing any part of it by any means without permission. You are supporting authors and enabling Penguin Random House to continue to publish books for everyone. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner for the purpose of training artificial intelligence technologies or systems. In accordance with Article 4(3) of the DSM Directive 2019/790, Penguin Random House expressly reserves this work from the text and data mining exception.

Typeset in 11/14pt Minion Pro by Six Red Marbles UK, Thetford, Norfolk Printed and bound in Great Britain by Clays Ltd, Elcograf S.p.A.

The authorised representative in the EEA is Penguin Random House Ireland, Morrison Chambers, 32 Nassau Street, Dublin D02 YH68

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library isbn 9781784746124

Penguin Random House is committed to a sustainable future for our business, our readers and our planet. This book is made from Forest Stewardship Council® certified paper.

In memory of Audi Bayley (1942–2024) with gratitude for her generosity and many kindnesses to Murdoch scholarship

Dear Reader.

Introduction

Imagine it for a moment. The attic.

A steep staircase up, with narrow gauge steps and close walls. Or a pull-down ladder, perhaps, standing almost vertically after it’s been tugged and shuttled down and has arrested on the floor, the handrail an essential grip to help you climb. There’s a dark void above your head, and cool draughts of air breathe from its entrance. There’s a whiff of mustiness, aging storage, long-held secrets. This attic holds literary gold, stashed in a private oak chest, and you’ve been invited into the story of its discovery.

So you ascend.

Up in the vault there are architectural-grade cobwebs, brushing against your cheek. Spiders hide behind sacks of envenomated prey as you switch on the lights – a few single overhead bulbs, buzzing and tinking, casting weak luminescence into the darkness. If you like, imagine no electricity to help you see, only shafts of bright Oxford daylight filtering through gaps in the roof, spokes radiating – as fatefully as cinematic illumination – towards a dark wooden trove.

The attic’s diminutive space is packed with bric-a-brac and artefacts: old suitcases, desiccated magazine bundles, boxes of clothes – daggercollared shirts, woollens, tunics – broken clocks and paintings, things tipping and teetering in all directions. There’s the slightly sour lime and dust smell of avian and rodent activity. Perhaps you want to hear a very English, cast-iron bell sounding across the city. Perhaps the scuttering of claws on the roof coping or inside the walls, mice, shrews. A crow cackling from the gable end, a sound moderately and appropriately gothic for this subject.

And there it is. The chest, once half-hidden by life’s archived detritus, is now revealed: it’s waiting for you, sitting squat as a prophet in a clearing, because you already know what you’re looking for up here, whose house this was and what treasure awaits you.

But what kind of chest is it – a hope, a casket, a blanket? Panelled, utilitarian or bracketed and footed, storing linen or guns or grain before her notebooks? Is there an old-fashioned bow key to turn in the lock –its mechanism still slick and perfectly functional – before the heavy lid can be raised? Imagine the moment of revelation however you wish, but one thing is certain – the sheer, exhilarating thrill of finding the unpublished poems of Iris Murdoch.

Now, if you don’t want to leave the reverie of re-enacted discovery, sit up here in the attic on a stack of old newspapers or the wobbling remains of a stool, with the candid little creatures and the floating dust, and flick through the notebooks. You’ll have to make head and tail of the handwriting, the crossings out, the additions, the versions, but you will see how artistic the edits were, how earnestly she crafted her pieces over the years. Let’s say the best editions will become apparent, in the way of epiphanic plots, their text lifting out towards you like magic-eye pictures. Or, if you are satisfied by your vicarious attic adventure and your haul, retreat, climb back down into the real world. Sit with this book in a comfortable armchair in your own home, or on your commute to work, glancing up to see a fellow traveller reading a novel with a familiar cover –yes, one of hers – or sit in your favourite café while cups and saucers chink and friends gossip, and read an extraordinary collection of poetry.

You’re probably curious. Why were these works sequestered and held back for so long? Something explosive, scandalous or sacred in them, maybe. Are they confessions? Or are they off-cuts and undermakes – lesser somehow than her established literary pedigree warrants? What might be expected of one of the leading novelists of the twentieth century, a decorated titan of fiction, when it comes to a ‘secondary’ discipline? A trained classical scholar. A philosopher. A woman who was the target of identity politics for decades, parts of her nature closeted then exposed, speculated upon, judged, as women are, for her passions, her proclivities and her relationships, as well as her work. She’s been the subject of biopics, biographies, countless dissertations. She’s familiar to you, known, intriguing, still somewhat mysterious.

xii

Iris Murdoch was a writer of formidable and industrious intellect, playfully mischievous around taboos; she was extremely concerned with concepts of goodness, wickedness, our human affect, and her work was immune to the fashions of fiction. Throughout the novels there are gothic and mystical tropes, conundrums, sublimations, scenarios that tease and test morality. Characters languishing, hiding in plain sight, hopeful for things not happening – perhaps we might call them ‘starfishers’, like the girl in her youthful poem. If her published stories do not wear the personal overtly, will her poems bring you closer to an innermost self, a private source, aspects of Iris not previously disclosed on the page? Is this thing in your hands a Liber Veritatis?

Truth. That jinking will-o’-the-wisp, that slippery, shapeshifting charmer.

‘Honesty is a hard thing,’ Murdoch notes in these pages, though she does nevertheless hope to be tethered, as ‘truth’s prisoner in the end’. How tempting to want to get at the heart of a writer, find what makes her heart tick. Especially a writer with such vast talent, status and persona, with quite complicated dramas around her life. Her observation does beg the question – within the construct of words, might we ever really trap truth, arrest its flight, interrogate and hold it to account? A novelist must have persuasive command of language and extensive representative abilities, so as to convince readers of believable virtual worlds, a realistic cast and viable propositions. Is a poet more able to dispense with the makery-uppery of long form, distil subjects to essence, pin a thing truly?

Again, Murdoch can guide on this matter. Her poems are often beautifully formal songs, sonnets, ballad templates, tight in composition and following structural rules, rhyme and rhythm. They take in traditions, her nationalities, poetic legacies, and in doing so they often act as sprung, performative devices, tricksy boxes of ideas and emotions. As she herself states, they ‘play a game to tell the truth’.

Which is not to say there isn’t a wincing, or thrilling, intimacy to them, depending on how you’re minded. They are both frank and

xiii

withholding; they are contradictory, complicated, like she was (like you are, and I am). In her poems, she seems to be trying to work her life and her self out, sometimes physically, sometimes politically, to ‘process’, as we might say now. But they do not seem overly therapeutic, and they completely resist solipsism, the deep well of me-ism. They are neither salacious nor gnomic, but pitched between poles, a territory where she must have felt able to confide and still be mindful. Encoded or openly, they often address her lovers – those both desired and achieved, unconsummated and resisted – as well as her spouse. They include her troublesome liaisons, relationships that vexed and damaged as well as elated her. Anguish, despair, longing, bonding. The many sensations of a lover are held in these lines. There’s the struggle and occasional reconciliation with more difficult feelings, of guilt, lust, despair, heartsickness, possessiveness – a poem can be a strongbox, the perfect receptacle for such live emotional demons. Touching, and not being able to touch another body. Lovelorn states, anger and torment. The violence and darkness and reckoning of desire. She stows it all in wordy oubliettes – quite literally these poems resided for a long time in a place of forgetting.

There are also gentle communion poems, celebrating the safe ports and companionability of home and husband. Poems written for women she held relationships with, or wanted to, are especially ardent, complex, tender and gorgeous. These read not like imprisoned offences but more as vulnerable documents, wishes blown softly towards those who fascinated her, or away, released.

It is quite the poetic toolkit. Her range of tones is, in fact, remarkable – strident, self-effacing, humorous, deadly serious, god-stung, entreating, ironic. In places, there’s baroque gender wrangling, meditation on self and sexual reassignment. This, in an age well before open public discourse on non-binary existence, identity fluidity, bisexuality and polyamory, the assurances of orientation. Perhaps you might sense, though, that even if these distinctions had been available to her, she may not have adopted them, but rather would have continued to embrace

While there is a very broad spectrum of expression, experience and interaction within Murdoch’s poetry, one central and fundamental energy, one character, keeps showing up. Love. Love is embodied. The poet frequently meets and communicates and even grapples with Love, who goes about the pages in semi-corporeal, semi-deified form, charging the poet, helping the poet, hindering the poet. A gatekeeper, a gamekeeper. A rider, a drowning oceanic creature. Masked. Bemused. Almost avenging. Love jokes and judges; it is instructive, lawyerly, sparring, waiting roadside like a ragged oracle or appearing as a rescuer after a fall. Love becomes more significant than a lover, even. Submitting to the truth of feelings, to the emotion and power and meaning it brings, if not to a human candidate, is in a way the ultimate truth to be found within this book, should one still be needed. It is the collection’s colophon.

Wherever and however Murdoch might be located in the writing, the writing itself is wonderful, animate and effective, creating spaces that are visual and sensual and experiential, as you might expect. The skill with which she writes verse is undeniable. She has an ear for music, understands cadence and verbal acrobatics. She might produce work that is blunt cut, or she might feather. She retains the novelist’s gift for narrative quickening and landscaping, atmospherics, activation of scene and scenario, and she applies these skills to poetic forms.

She is, aside from everything else, an exceptional nature writer, going toe-to-toe with heavyweight pastoralists, the rugged rural bards that were her contemporaries, producing lines so well observed and imagistically rendered you might assume it was her day job, rather than auxiliary. Murdoch’s ‘Fox’ – that seemingly requisite topic of all twentiethcentury British nature poets – equals any other poemy fox in the annals. It is sudden and brilliant. She is superb at weather, a ‘segment of rainbow . . . still in action’, and trees, pine boughs ‘damp with resin, dry

xv the versatile, surprising, unclassifiable natures of identification. For all you might pass through a few more layers towards her core via this work, that core remains categorically protean.

with cones, rustling like rising bones’. The sea provides a female reliquary, a ‘wave-washed bone-white’ shell whose ‘tender hinge’ becomes downright erotic.

The ‘strong and skilful strokes’ of her Diver, from the ‘Juvenilia’ section of the collection, might well be a description of her own technical ability with a pen in the making of the poems you now hold. What can clearly be ascertained, from her early attempts through to those written later in life, is an astonishing talent, which she nurtured, and humbled, and hid, but did not abandon. Though draft after draft may have been kept aside, reservedly, none are unworthy of her hand or her mind, none are mediocre.

Yes, perhaps when you finish reading and close this book, you might feel a little closer to Iris. You might feel satisfied or edified or disquieted by having had additional access to her personal life, revelations about her heart, and the hearts of those in her romantic orbit. There may be verification of her relationships here, records in the library of lovers and friends, intimate glimpses of her ways of being and relating.

But don’t forget, poems play games to tell the truth; no singular soul or definition of personality can be found in this literary form, or perhaps in any other. All writing is a version of veracity, isn’t it, no matter how moving or permissive or authentic? Who among us, dear reader, can be fixedly known by what we write, and place discreetly in the attic?

Sarah Hall, 2025

Editors’ note on the text

This anthology has been compiled principally from the poems contained in ten poetry notebooks and the typescript entitled Conversations with a Prince found in the attic of Iris Murdoch’s home in Oxford in 2016. All these materials are now held in the Iris Murdoch Collections in Kingston University Archives and are available to view by appointment by contacting archives@kingston.ac.uk. Two copies of the Conversations with a Prince typescript are also deposited in the Brotherton Library at the University of Leeds.

Murdoch dated her early poems with the day, month and year in which they were composed, while later poems are identified only by year. This collection largely follows a chronological order with a few poems not in strict sequence to allow those that complement each other to be placed together. Poems are listed by title or, if untitled, by all or part of the first line of the poem in quotation marks. Italics have been used for words that were underlined by Murdoch herself for emphasis.

The Conversations with a Prince section of this collection is dated circa 1963, the year Murdoch sent the typescript that contained these poems to her editor, Norah Smallwood, at Chatto & Windus. However, the poems were written during the 1950s and revised over a number of years. One additional poem, ‘I Overcome Love’, was taken from a notebook and added to this section as it clearly resembles the style and content of the sonnets included there.

When Murdoch includes a dedication, she usually writes ‘for’ with the dedicatee’s initials added. She also notes that some poems were written ‘with’ a person, and we believe that these were composed either in the company of that person or were inspired by them. Perhaps for reasons of discretion, no dedications appear in the Conversations with a Prince typescript, but if one is included in her notebook version of the poem, we have reinstated it here.

For clarity, the name of each dedicatee appears below the poem title in brackets. Murdoch did not include a dedication to Elizabeth

Anscombe alongside the poem, ‘The dear and detailed dream of your carved head’ but research evidence suggests strongly that Anscombe is Murdoch’s intended subject. Similarly, references to various other inspirations for poems have been placed below the title. Further brief biographies and relevant background information to the poems can be found in the end notes.

We have included what we believe to be the most skilful version of each poem with as much sensitivity and accuracy as possible. Previously published poems are either taken from the original publications, or a notebook version if we believe they are more accomplished.