THE LOST SURREALIST

HENRY ORLIK’S QUANTUM REVOLUTION

“I remember Henry as something of a loner and an outsider but one of the most uniquely gifted, stubborn, fearless characters I’ve ever met. He took everything to extremes, did nothing half-heartedly, and bounced from rags to riches and back again throughout his life.”

24 October 2025 – 14 March 2026

Public exhibition at

WINSOR BIRCH

The Fine Art & Sculpture Company Catalogue sponsored by

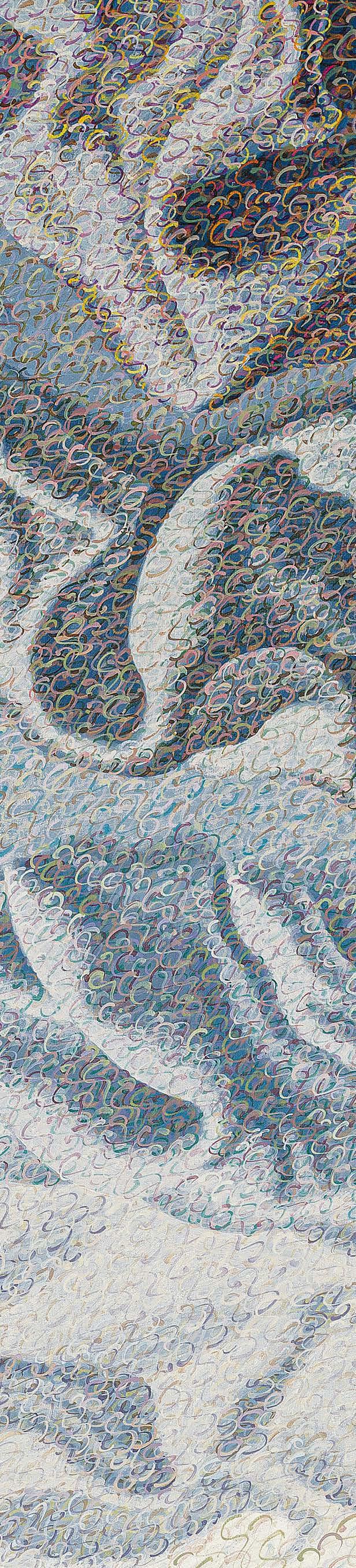

Cover image: The Parting, c. 1975-1978. Acrylic on canvas. 122 x 86.5cm.; 48 x 34in.

HENRY ORLIK’S QUANTUM REVOLUTION

– 2025, David Gould, artist, and Henry’s friend from Gloucestershire College of Art

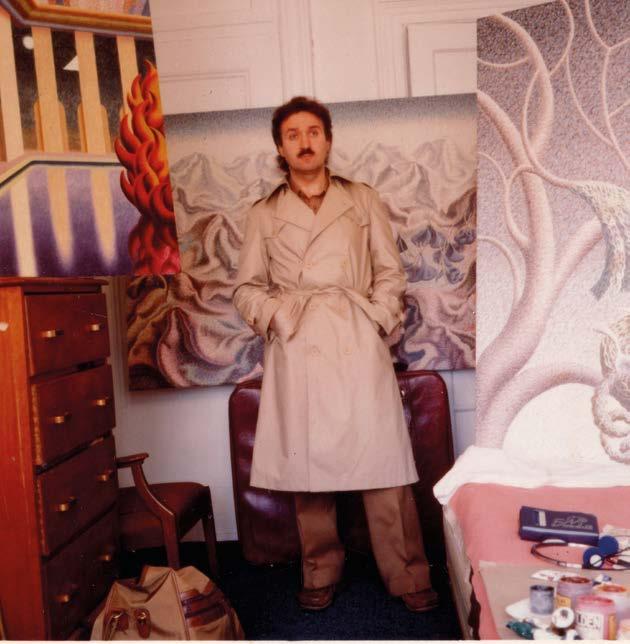

Henry Orlik, 1982

INTRODUCTION

By Katie Ackrill, Collections and Exhibitions Officer

When Winsor Birch’s exhibition Henry Orlik: Cosmos of Dreams hit the press in August 2024, word about Orlik and his astonishing work quickly reached the team at Museum & Art Swindon. We learnt about a young man who had arrived in Swindon in 1959 as part of the town’s large Polish diaspora, and trained at the Swindon School of Art. We learnt about a rising star, who established a reputation as an exciting and technically gifted artist, and showed his work alongside masters of surrealism. We learnt that his name and his work had become obscured, because he spent the next 50 years painting behind closed doors, quietly amassing an incredible body of drawings and paintings.

Now that Orlik’s work has been launched back into the public sphere, people are once again astounded by his dream-like worlds, fizzing and humming with the energy of his unique “excitations”. Referred to as a “surrealist master” and a “surrealist art star”, Orlik is now gaining the recognition he deserves.

The Lost Surrealist: Henry Orlik’s Quantum Revolution brings Orlik’s work to a public museum for the very first time, enabling a broader audience to discover and enjoy his talent, through a thoughtful selection of paintings and works on paper. As the home of a significant collection of modern and contemporary British art, Museum & Art Swindon celebrates Swindon’s creative heritage alongside the most iconic artists of 20th century Britain. It is therefore fitting that Orlik, with his national profile and local significance, is celebrated as part of our programme.

Museum & Art Swindon would like to thank Grant Ford and the hard-working team at Winsor Birch for giving a huge amount of time and experience to our partnership. We would also like to thank our generous lenders, for enabling us to borrow significant artworks from Orlik’s oeuvre and make them publicly accessible. Finally, we say a huge thank you to Henry Orlik, for allowing the world to find joy in his incredible creative vision.

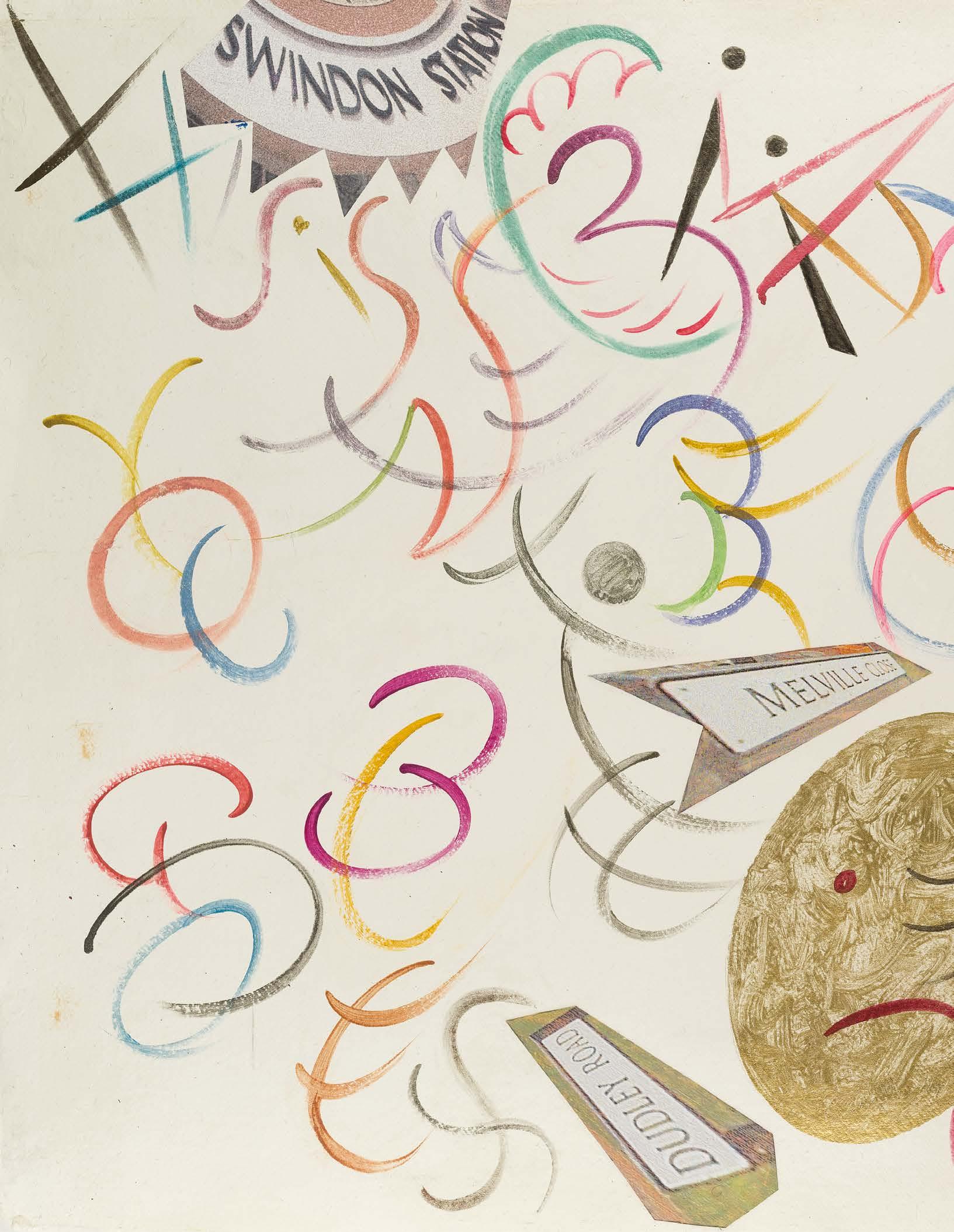

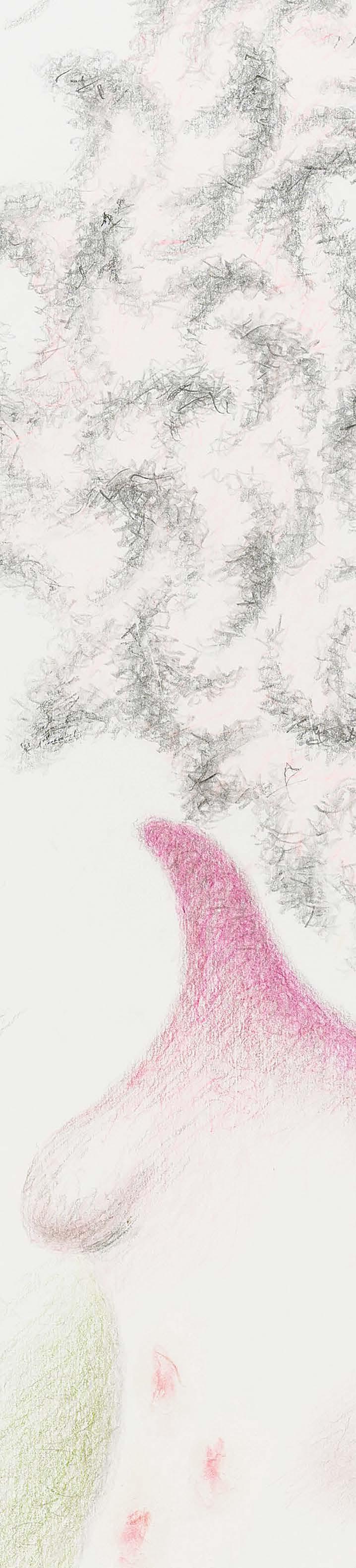

Left: Fairground, c. 1983

With artist’s stamp lower right Coloured crayon and pencil

38 x 38cm.; 15 x 15in. Private USA Collection

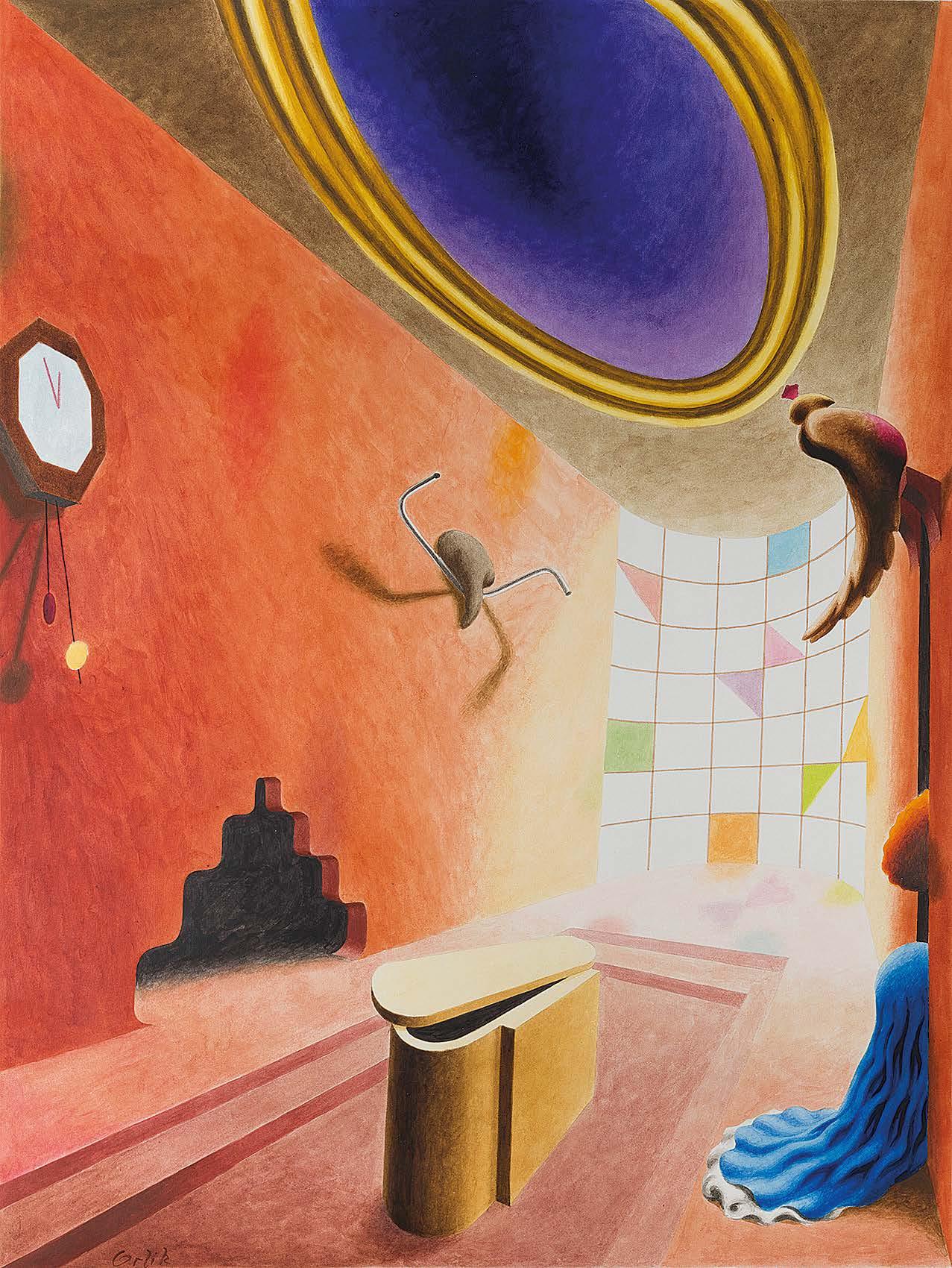

The Landlord, c. 1970-1975 Acrylic on canvas 63 x 53cm.; 24¼ x 20¾ in. Private UK Collection

FOREWORD

In early 2024, I experienced something that transformed my life and changed my career forever. I was confronted with extraordinary and striking paintings unlike anything I had seen in forty years in the art world, including my thirty years at Sotheby’s. These paintings vibrated with electric energy; they were covered in thousands of tiny, precise spiral brushstrokes that seemed to record consciousness itself. I was looking at the work of Henry Orlik, a name I had never heard, an artist the world had forgotten.

Henry Orlik, born as a displaced person in 1947, spent over forty years developing what he calls “quantum painting” in complete isolation. While the art establishment moved on without him, he quietly revolutionised how paint could capture the vibrating energy of thought itself. Drawing from quantum physics, he understood that matter at its smallest level exists in constant vibration. His paintings make this invisible energy visible, creating surfaces that pulse with life even when depicting personal struggles. Each mark represents what he calls “qi: a cosmic spirit that vitalises all things.”

This wasn’t just abstract theory but lived experience, rooted in childhood memories of stained-glass windows at Fairford Camp casting “amazing reflections and shadows on the floor”, patterns of light that influenced his art for decades. Having always appreciated the Pre-Raphaelites and their meticulous application of beautiful glazes, I wonder: what would they have thought of Henry’s work, with its equally careful detail and deep meaning?

In 2022, Henry suffered a devastating stroke that ended his ability to paint. The following year, a bureaucratic catastrophe struck: decades of his final works were “removed and disposed of” when he was evicted from his London flat. An entire chapter of revolutionary art vanished. Yet from this loss has come recognition, arriving not a moment too soon for an elderly and frail artist. The tragedy intensifies the triumph.

Since first viewing Henry Orlik’s paintings in 2024, I have been fully immersed in Henry’s world, and his remarkable work has now featured in many major publications and been displayed from London to New York. One prominent institution has acquired a piece for its permanent collection. International recognition has come, showing that delayed genius is not denied genius.

Henry rarely signed or dated his works; they remained deeply personal to him, and his rejection of the commercial art world made them even more secretive and intimate. This creates a fascinating juxtaposition: an artist desperately wanting to be received yet standing his ground against a system with which he could not compromise. Every mark in his painting is implicitly his autograph. The dating of the works remains an ongoing, changing process as we learn more about this artist who has been reclusive for over forty years.

Our collaboration with Henry occurs at a remarkable moment for Surrealist art worldwide. The centenary of Surrealism has garnered unprecedented scholarly and institutional interest in the movement. There is strong demand for exceptional Surrealist works exemplified in the outstanding sale of Pauline Karpidas’s collection in September 2025 at Sotheby’s London, just a short walk from where Henry had exhibited alongside masterworks by Magritte, Ernst, de Chirico, and Dalí at the Acoris Gallery in Brook Street during the 1970s.

One cannot help but wonder had Henry been embraced by the right dealer and nurturing agent back in the 1970s, had someone like Pauline Karpidas encountered his work during her legendary collecting years, his story might have been different. Karpidas’s sale indicates the significance of Surrealist works and Henry’s technical mastery and philosophical depth easily match those of the Surrealist masters, whose works are considered priceless.

Henry’s mature work has developed into something entirely original: a visual language that captures the quantum mechanics of consciousness itself. The United Nations has declared 2025 the International Year of Quantum Science and Technology, recognising that quantum thinking is transforming everything from computers to communications. Henry was exploring these ideas in art long before they entered mainstream conversation. His “excitations”—those thousands of spiralled brushstrokes—generate energy fields that go beyond traditional surrealist imagery.

Henry’s quantum method transforms everyone who encounters it. His paintings demand patience; you must slow down, look carefully, and learn to read consciousness made visible. A few visitors at the London and New York exhibitions were drawn to tears, not from sentimentality but from recognition. They discovered an artist who reveals the deepest currents of human experience, demonstrating how small changes in attention and awareness can lead to profound transformation.

Alistair Amos, a clinical psychologist, visited our first show in London in 2024 and has followed the renaissance of Henry’s work since. He wrote to me: “I was enthralled by Henry’s story and his mesmeric worlds. I find something deafening that echoes in Henry’s art which is mirrored in his own story and our societal world of cultural and systemic matrices, constructions, rules and interdictions which protect and trap but also shape us. The biopsycho-social effect this has on our behaviour and on our mental health are significant. Henry reminds us that we should pay greater care and attention to those around us, and the responsibility we have to advocate for others who may be at risk of abuse and neglect not just from individuals but from faceless systems.”

This exhibition has been immeasurably enriched by the scholarly research of Sara Clemence, who has worked with me for nearly a decade as academic writer and researcher. Sara’s patient visits to Henry have been fundamental in discovering more about this enigmatic artist. Despite Henry’s natural wariness, Sara has forged both intellectual and emotional connection with him, bringing moments when his eyes brighten and lucid memories surface, revealing the depth of thought behind his revolutionary method.

I would like to express profound gratitude to Katie Ackrill and her exceptional colleagues at Museum & Art Swindon for their unwavering support in bringing this historic exhibition to life. Their commitment demonstrates the very best of curatorial vision and institutional dedication. I also thank my colleagues at Winsor Birch for their unwavering support throughout this challenging and extraordinary journey.

This exhibition represents profound historical significance: Henry Orlik’s first public loan exhibition, taking place not only in the town where he spent his childhood but also at one of Britain’s true hidden gems. Museum & Art Swindon houses what Art UK describes as “one of the most remarkable collections of its kind outside London.” Artists in the collection include Ben Nicholson, Henry Moore, Lucian Freud, Graham Sutherland, L.S. Lowry, Paul Nash, Terry Frost, Howard Hodgkin, John Hoyland, Richard Hamilton, Gwen John, Augustus John, Maggi Hambling, and Grayson Perry. These are some of my most cherished British artists, and the fact that Henry’s revolutionary quantum paintings now join this extraordinary company feels like destiny fulfilled.

The collectors who purchased works through our international exhibitions have generously agreed to loan them back, recognising their role as custodians of valuable cultural artifacts. This is not just a rediscovery of art but a recognition of justice, honouring an artist whose resolve never faltered despite decades of rejection.

Sam Knight from The New Yorker recently described Henry calling me “a complete mystery” as I worked to bring his art to the world. But the real mystery is the sliding door moment in early 2024 that transformed everything. This is the profound mystery of art itself: how a chance encounter with genius can change not just careers, but souls. Henry Orlik and his incredible work have changed my life forever.

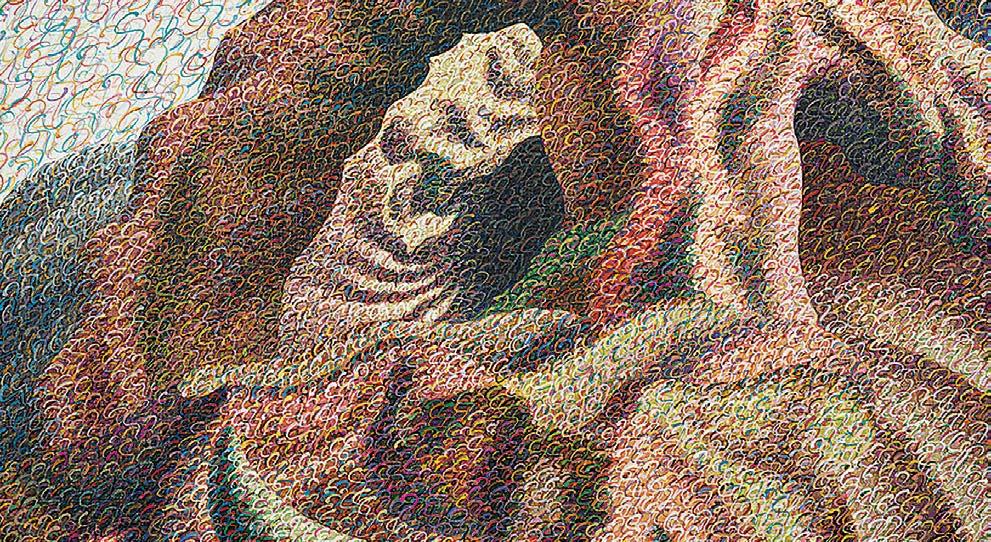

Oasis, c. 1971-1973

With artist’s stamp verso Acrylic on canvas

86.5 x 71cm.; 34 x 28in.

Private UK Collection

Henry Orlik, c. 1970

“He is the pictorial architect of strange buildings, the inventor of fanciful shapes

on which

he

lavishes a minuteness of colour, with the declared intention of making every square inch a painting in itself. It would not be out of place to call Orlik, a surrealist. He has the poetic aptitude for seeing one form in another.”

– William Gaunt, The Times, 1978

Henry’s quantum method suggests that consciousness actively influences reality through the mechanisms of attention and intention. Each moment you spend with one of his paintings, you become part of the evolution. Orlik has demonstrated that painting can do more than merely depict reality; it can genuinely alter how we perceive and think.

The lost surrealist has been rediscovered, but his revolution is only just beginning. Henry Orlik has provided us with the tools to see things differently. Now, the work of transformation rests with us.

Grant Ford

Curator

All enquiries relating to Henry Orlik’s life, work and reward for finding his lost paintings, should be made to: Winsor Birch, 1 The Parade, Marlborough, Wiltshire, SN8 1NE enquiries@winsorbirch.com +44 (0) 1672 511058

EXHIBITION WORKS

for Lucyna

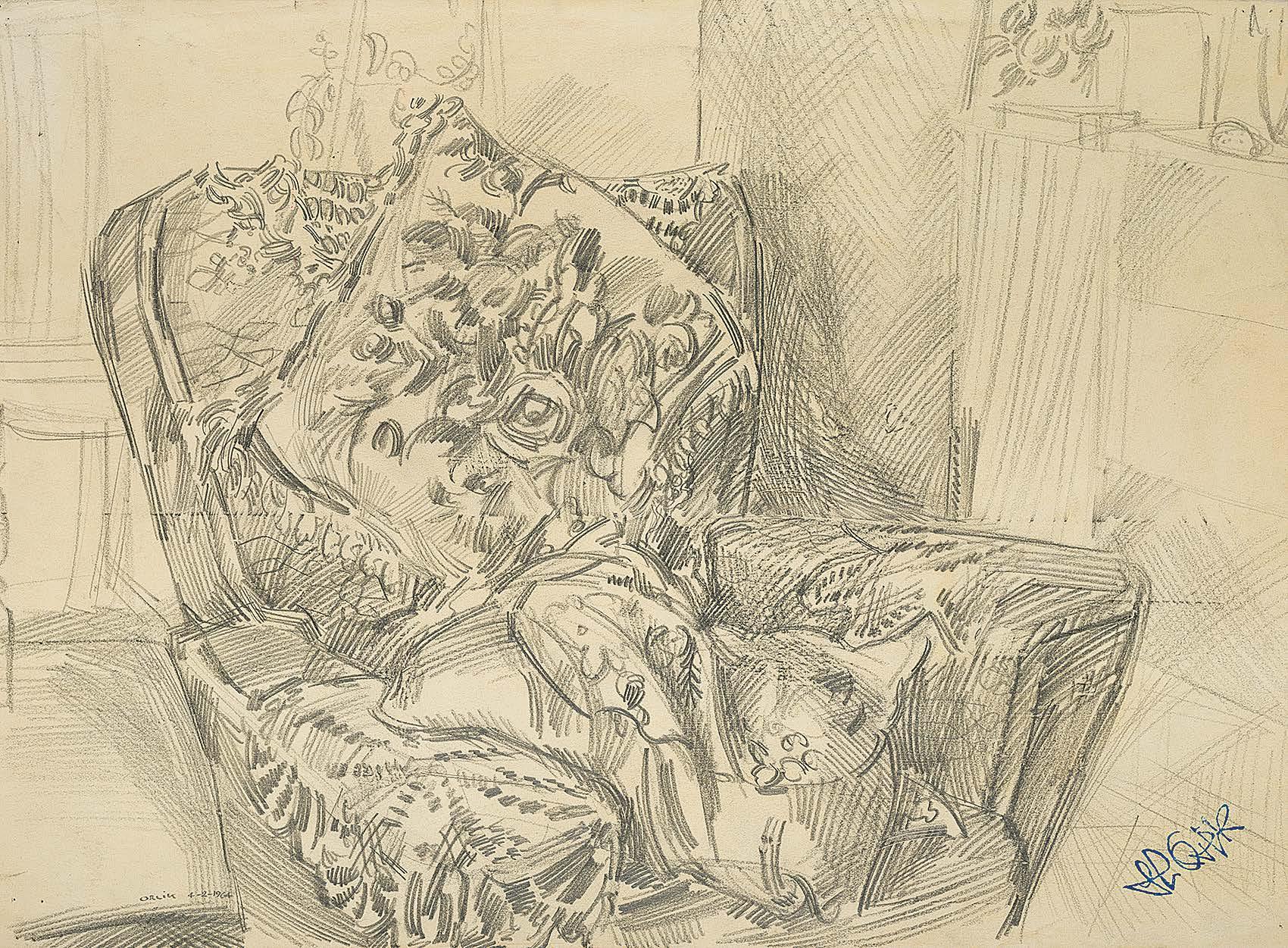

1. Armchair, 1964

Signed and dated lower left: ORLIK 2.4.64

With artist’s stamp lower right

Pencil

34 x 46.5cm.; 13¼ x 18¼in.

Provenance

Private UK Collection

At seventeen, Henry Orlik possessed draughtsmanship that could breathe life into domestic objects. This pencil drawing, signed and dated 4th February 1964, demonstrates this technical mastery, revealing an intuitive understanding of how furniture absorbs human presence. The armchair emerges not only as an object of study but also as a silent witness to family rituals, its upholstery rendered with such intimacy that we sense the weight of countless evenings settled into its embrace.

This particular armchair carries significant biographical weight. Its substantial form and ornate decoration suggest the kind of furniture valued by refugee families: pieces symbolising stability after displacement. For the Orlik household, recently settled in Swindon after years in camps, such an armchair would embody hard-won domesticity. The careful detail implies deep familiarity, this chair was part of daily life, perhaps serving as Henry Orlik’s father, Jozef’s, evening refuge after factory shifts, where the Polish war veteran could finally rest in his own domain.

The drawing’s compositional mastery shows remarkable sophistication. The chair occupies pictorial space with regal presence, positioned at a slight angle that suggests both welcome and grandeur. Unlike student exercises that treat furniture as a neutral form, Orlik understands how domestic objects gain personality through use. The subtle asymmetries in cushion compression and the way fabric drapes according to gravitational memory all reflect an artist who discerns life rather than simply replicates appearances.

What elevates this study beyond mere precocity is its psychological sophistication. The chair waits with patient dignity, neither asserting dominance nor blending into background decoration. Its presence suggests the kind of furniture that witnesses family conversations, evening reading, quiet arguments resolved through proximity rather than words. For a displaced family rebuilding domestic life, such objects provided continuity with European traditions whilst adapting to English circumstances.

The date 4th February 1964 positions this work within Britain’s cultural transformation, as traditional values encountered the commercial imagery of Pop Art. Yet Orlik’s approach remained rooted in careful observation and psychological exploration. This seventeen-year-old artist already understood that the most radical artistic statements often emerge through patient engagement with humble subjects rather than the pursuit of fashionable innovation.

Armchair shows how extraordinary vision develops: not through sudden inspiration but through disciplined attention to immediate surroundings. In this modest pencil study, we see the start of a career that would last for decades, proving that artistic greatness often reveals itself quietly, through the simple act of seeing familiar objects with unprecedented clarity.

“…the furniture preserving the memory of loves and hatreds …”

– Czeslaw Milosz, The Captive Mind

2.

Defeat, c. 1970-1972

Mixed Media on Card

79 x 52cm.; 31 x 20½in.

Provenance

Private UK Collection

Exhibited

London, Acoris, The Surrealist Art Centre, Henry Orlik, 1972 London, Winsor Birch at the Maas Gallery, Cosmos of Dreams, 9-20 August 2024

“You’re defeated before you’d even started. ... No money, nothing. ... They thought of me as nothing.”

– Henry Orlik

Defeat, was created at the start of Orlik’s artistic career, during a period of profound personal crisis, when he endured poverty and artistic rejection in a London bedsit. The work serves both as exorcism and as a meditation on what Orlik termed life’s fundamental “jeopardy”: existence’s essential precariousness. Combining environmental premonition, spiritual symbolism, and the first glimpses of his revolutionary quantum painting technique, Defeat carries a fresh relevance today, speaking to the fears of contemporary audiences as they grapple with survival and meaning in an age of uncertainty.

“Anything can happen,” Orlik later remarked of this canvas, a phrase weighted with experience. As a young artist just out of Gloucester College of Art, he already felt his dreams threatening to collapse before they had even begun. In the upper right corner, a sleek aeroplane suggests both escape and abandonment; its cruciform silhouette echoes the Orthodox crosses scattered across the surface of the dome, hinting at how spiritual symbolism infiltrates even our most modern, technological imagery. Yet this is not a conventional religious painting. Orlik dismantles institutional authority, presenting spirituality as something to be earned through direct experience rather than inherited tradition.

The painting’s surface vibrates with Orlik’s “excitations”: thousands of minute, spiralled brushstrokes representing the excited state of quantum particles reacting to external stimuli. Even in this early work, painted before his full development of the quantum painting method, his excitations generate a field that vibrates like an overloaded nervous system. As Orlik later explained, each mark embodies qi, a “cosmic spirit that vitalises all things, giving life and growth to nature, movement to water, and energy to man.”

At the centre, a flowering plant painted in luminous magenta embodies both vulnerability and defence. Bristling with thorn-like crosses, it transforms from a simple botanical specimen into a sacred mandala, symbolising consciousness itself: fragile, besieged, yet irreducible. Orlik later remarked, “Christ is in every man, but not everybody is though.” The flower, marked at every edge with the cross, embodies this paradox of universal potential and individual failure.

Defeat can be understood in dialogue with Surrealist precedents. Whereas Max Ernst’s Two Children are Threatened by a Nightingale (1924, Museum of Modern Art, New York) depicted innocence under assault, Orlik’s flower asserts defensive power. Where Paul Nash’s Totes Meer (1940–41, Tate, London) translated destruction into a metaphysical seascape, Orlik retained hope within catastrophe. His bloom continues to flower even as disaster looms.

The suspended boulder above the flower intensifies the sense of metaphysical jeopardy. Forever poised yet never descending, it creates an atmosphere of tense anticipation reminiscent of René Magritte’s explorations of suspended time. Unlike Magritte’s The Treachery of Images (1929, Lacma, Los Angeles), which questioned the relationship between representation and reality through intellectual puzzles, Orlik’s suspended catastrophe speaks to lived experience: a reminder that we live under constant threat of collapse, yet somehow beauty persists, love continues, creativity flourishes despite rather than because of our security.

Below, the flooded landscape depicts Los Angeles’s Sixth Street Bridge partially submerged, its Gothic Revival arches rising like ribs of a drowned cathedral. Orlik saw such landmarks as fragile anchors, and their partial submersion under water reflects both environmental foreboding and the disorientation experienced by someone living between cultures: where familiar places remain visible, yet somehow out of reach. The hybrid architecture recalls medieval cathedrals, Islamic minarets, and Art Deco towers simultaneously. It is architecture belonging to no single geography or period, but to the fractured vision of the displaced artist. The bridge leads nowhere—as Orlik noted, “not meaningless, but without a destination”, a perfect metaphor for the immigrant condition where movement becomes perpetual without ever achieving arrival. Architectural submersion carries additional resonance compared to other flood paintings in art history. Its flooded landscapes anticipate the rising seas of our own era with a prescience comparable to Turner’s industrial visions. Yet where Théodore Géricault dramatised survival against catastrophe in The Raft of the Medusa (1819, Louvre, Paris), Orlik presents the flood as accomplished fact. The task is not resistance but adaptation: consciousness must learn to endure beneath transformed conditions.

Orlik’s chromatic orchestration operates with extraordinary emotional precision. He composes a symphony of blues, from powder azure to deep cerulean, establishing both atmospheric depth and melancholic tones that would define his later canvases. Against these tonal depths, the warm magentas of the flower blaze with vitality. Unlike Yves Klein’s monochrome explorations in IKB 191 (1962, Private collection), which emphasised aesthetic purity, Orlik’s use of colour carries psychological weight: each hue functions as a tool to transform emotional chaos into harmony, despair into resilience.

Biographically, Defeat proved prophetic. Feeling crushed by rejection, Orlik withdrew from commercial engagement, living reclusively to develop his method in isolation. This trajectory echoes Yves Tanguy’s career, whose later works such as Multiplication of the Arcs (1954, MoMA, New York) achieved similar psychological intensity through isolation, though Tanguy’s forms remained abstractly biomorphic, while Orlik’s maintained connection to recognisable reality.

Within the broader context of 1960s British Art, Defeat occupies unique territory. Unlike Francis Bacon’s Three Studies for Figures at the Base of a Crucifixion (c. 1944, Tate Britain, London), which depicted human anguish through expressionistic distortion, Orlik’s approach maintained compositional clarity. While Pop artists like David Hockney embraced reproducibility in works such as A Bigger Splash (1967, Tate, London), Orlik turned to quantum physics for metaphors capable of articulating consciousness itself.

Ultimately, Defeat fuses autobiography with universal significance. Its early use of the excitation method reveals Orlik’s ambition to visualise reality as a quantum field of interconnected phenomena. The flower’s persistence amidst jeopardy, the submersion of cultural landmarks, the aeroplane recast as cross: all converge to articulate an enduring truth- that beauty and consciousness endure even in the face of collapse.

Unlike Pop’s immediacy or Conceptual art’s intellectual detachment, Orlik demands sustained attention. His surfaces, like illuminated manuscripts, reward close viewing with endless discovery. In this sense Defeat invites contemplation, linking modern painting with ancient meditative traditions.

As we look, the painting looks back. Its suspended catastrophe mirrors our own condition of perpetual threat, yet also of renewal. The boulder never falls; instead, it becomes the source of possibility. From crisis, Orlik conjured resilience. From jeopardy, he found beauty. From uncertainty, he created a vision of consciousness as indestructible. Defeat, paradoxically, becomes a work of triumph: proof that even in life’s most precarious moments, the creative spirit endures.

3.

Oppressed State, c. 1970-1972

Acrylic on plastic, reverse painting

88.5 x 97.5cm.; 34¾ x 38¼in.

Provenance

Private UK Collection

Exhibited London, Acoris The Surrealist Art Centre, Henry Orlik 1972

Henry Orlik’s Oppressed State presents a prescient vision of systematic control, resonant with present concerns about surveillance, spectacle, and environmental manipulation. Executed in reverse painting on plastic, its very method unsettles perception, foregrounding effects before causes and producing a depth that shifts with every glance.

A fairground helter-skelter, rendered in vivid carnival hues, masquerades as amusement yet operates as distorted version of Jacob’s ladder. Aspiration is reduced to mechanical repetition, spiritual promise is reconfigured as bureaucratic processing. Adjacent left to the helter-skelter, a theatrical stage evokes the spectacle of domination, a cannon-like hybrid of organic strands and mechanical precision exemplifies instruments of control that adapt and evolve. Balloons hover ominously, recalling both defensive wartime measures and latent weapons. Most chilling is the watchtower, ambiguous in function; administrative, residential, or commercial, its surveillance is so seamlessly integrated that it appears ordinary, even reassuring.

The genesis of this vision lies in Orlik’s biography. His Belarusian mother, Lucyna, survived Nazi labour camps, while his Polish father, Jozef, served with Allied forces. These contrasting vantage points of endurance within and resistance without instilled an acute awareness in Orlik of how authority operates both through brute force and through subtle conditioning of environment and psyche. Where Bruegel’s Tower of Babel (1563, Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna) revealed the confusion of human ambition thwarted by divine decree; Orlik’s spiral structure speaks instead of bureaucratised aspiration, endlessly recycled. Piranesi’s Carceri d’invenzione (c. 1749-50, British Museum, London) conveyed oppression through fantastical prisons, yet Orlik’s horror lies in recognisable forms; fairs, stages and towers are repurposed as instruments of control. The bright carnival hues conceal structural entrapment, warm tones offer a veneer of domestic comfort, and cool surveillance blues render authority systematic rather than personal.

Hannah Arendt observed how totalitarianism reduces political action to mechanical response; Orlik’s helter-skelter literalises this insight. Michel Foucault analysed the panopticon’s psychological effects; Orlik extends the concept, envisioning observation naturalised into architecture. Equally, his imagery resonates with Guy Debord’s Society of the Spectacle and Borges’s “Lottery in Babylon”, both recognising the tyranny of systems that manipulate hope rather than fear.

Most disturbing perhaps is our complicity; the helter-skelter entices with fun, the tower reassures with safety, the balloons suggest protection. These structures operate precisely because they appeal to human desires for entertainment, security, and efficiency. Orlik foresaw systems in which control emerges less

from imposition than from our own participation. Contemporary digital platforms and urban infrastructures confirm his prescience, where promises of connection or safety mask mechanisms of sorting, processing, and surveillance.

When exhibited at Acoris in 1971 alongside Magritte, Tanguy, and Dalí, Oppressed State announced a Surrealism engaged not only with unconscious perception but also with political manipulation. By visualising how authority infiltrates environment and psyche, Orlik exposed what dominant systems prefer to keep unseen. More than fifty years on, the work endures as both diagnosis and warning. It demonstrates that freedom may erode not through overt violence but through environments engineered to make alternatives inconceivable. In its dazzling colours and sinister ambiguities, Oppressed State renders visible the subtle mechanisms of power, insisting on vigilance where complicity so easily masquerades as choice.

The Lying Plant, c. 1970-1975

Mixed media on card

87 x 60cm.; 34¼ x 23½in.

Provenance

Private Asian Collection

Exhibited

Marlborough, Winsor Birch, Cosmos of Dreams: Part II, 23 August-17 September 2024

“I

was once asked if my technique derived from our awareness of the atom-bomb and disintegration. On the contrary, although the post-war generations are innately aware of the atom-bomb, by treating each shape as if it were a world in itself, I wish to affirm its existence even to the invisible depth of its microscopic agitation of atoms. Not its transience but the strength of its existence.”

– Henry Orlik

Henry Orlik’s The Lying Plant shifts between the graceful elegance of a dancing figure and the terrifying grandeur of a nuclear mushroom cloud. Through his signature “excitations” technique, Orlik captures a central tension between beauty and destruction, truth and deception.

The composition unfolds in three tiers of undulating shapes, painted in soft grey and bruised pastels that evoke both human flesh and the ominous hues of atomic clouds. At the summit, a dark, rounded form tipped with a slender spur suggests at once an elegant jazz-age hat and the stem of a mushroom cloud, capturing the work’s central tension between elegance and impending catastrophe.

The painting’s connection to horror vacui, the fear of empty space, gains significance when examined alongside Orlik’s background. Born in 1947 in post-war Germany to parents who survived war and deportation, he inherited the atomic-era anxiety and displacement of his generation. The dense “excitations” of The Lying Plant read as an existential defence, a refusal to allow emptiness that might hide unspeakable horrors.

The painting’s layered structure and soft greens and pinks recall Hieronymus Bosch’s The Garden of Earthly Delights (c. 1490-1510, Museo del Prado, Madrid), however instead of showing a progression from paradise to damnation, Orlik compresses these into a single continuous moment. The dancer becomes the mushroom cloud, the cloud becomes the dancer. A temporal loop, intensified by the work’s curved 4.

“No man, when in his wits, attains prophetic truth and inspiration, but when he receives the inspired word, either his intelligence is enthralled in sleep or he is demented by some distemper or possession.”

– Plato (c. 300 BC), Timaeus, 71e-72b

forms, which distort space like Einstein’s curved spacetime. Its tripartite structure also echoes M.C. Escher’s Circle Limit IV (1960, Escher Foundation), compressing vast scales into finite space: the planet-shattering mushroom cloud coexists with the domestic scale of the dancer. This scalar tension produces a dizzying effect, mirroring the psychological disorientation of life under nuclear threat.

The title “The Lying Plant” carries multiple meanings beyond its reference to nuclear facilities. “Lying” suggests both falsehood and a horizontal deathlike position, hinting at the deceptions surrounding early atomic testing. The successful Trinity test enabled the U.S. military to deploy the atomic bomb, marking the start of the Atomic Age. Meanwhile, the word “plant” suggests organic growth, transforming the mushroom cloud into a perverse deadly bloom. The dancer becomes a celebration of this corruption, a danse macabre at the edge of apocalypse.

The work’s connection to Surrealism addresses deeper questions about the nature of reality. In 1974, Orlik’s paintings were shown alongside René Magritte, Yves Tanguy, and Salvador Dali in Surrealist Masters. Like Magritte’s The Treachery of Images (1928-29, Los Angeles County Museum of Art), which declares “This is not a pipe,” Orlik’s painting blurs representation and reality: the figure is both present and absent, the mushroom cloud both real and imagined. This ontological uncertainty mirrors the epistemological crisis of the atomic age, when matter itself revealed a stranger, more dangerous nature than ever before.

For Orlik, this painting represents his confrontation with early historical trauma. His father fought for the Allied Forces, while his mother survived a Nazi labour camp. Their displacement to England and life in refugee camps exposed him to how political forces can reshape lives. The Lying Plant turns this personal history into a statement about the hidden persistence of threat beneath apparent beauty.

In an era of climate crisis, pandemic, and nuclear tension, Orlik’s vision of beauty intertwined with destruction feels prophetic. The dancer endlessly transforms into the mushroom cloud, reminding us that humanity’s shift in consciousness from the atomic age is unfinished, we continue to celebrate technologies that could bring our own destruction.

The Lying Plant reflects the inherent ambiguity of human progress. Scientific discoveries that enabled nuclear weapons also brought benefits, just as artistic techniques can inspire both beauty and terror. Within Orlik’s wider oeuvre, it fuses personal history with universal themes. His withdrawal from commercial art reflects a refusal to compromise messages of urgency. In today’s world of global uncertainty, Orlik’s dancing nightmare feels both necessary and profoundly beautiful.

Right:

5.

Study for Antichrist – Female, c. 1971-1973

Pencil and watercolour

With artist’s stamp lower right 41 x 68cm.; 16¼ x 26¾in.

Provenance

Private UK Collection

Exhibited

Marlborough, Winsor Birch, Cosmos of Dreams: Part II, 23 August – 7 September 2024

“Surely some revelation is at hand …”

– William Butler Yeats,

‘The

Second Coming’

The Sacred Feminine and Creative Genesis: Henry Orlik’s Antichrist and the Annunciation of Grace

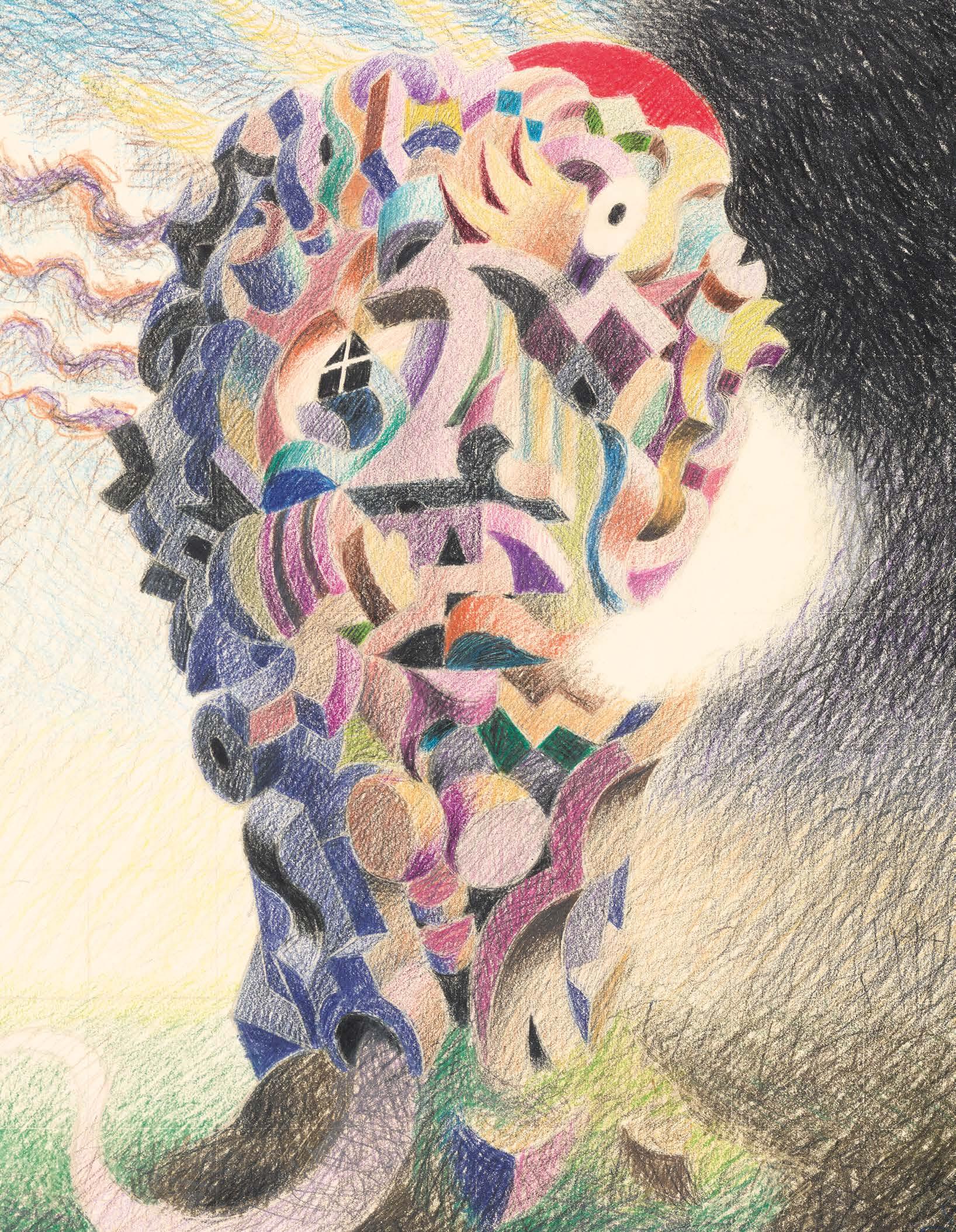

Henry Orlik’s 1973 masterwork Antichrist, considered alongside its two preparatory studies, constitutes a profound meditation on sacred femininity in 20th-century art. Instead of depicting opposition to divine creation, Orlik’s composition offers an alternative interpretation: “Annachrist,” the annunciation of grace through feminine creative agency. These works, created during Orlik’s exhibition period alongside significant paintings by Salvador Dalí and René Magritte, showcase his distinctive synthesis of quantum physics, Eastern philosophy, and Christian mysticism into a revolutionary visual theology.

Orlik’s signature “excitations” technique, involving thousands of meticulous brushstrokes inspired by quantum physics, produces compositions that vibrate with atomic-level energy. In his 1985 theoretical statement, he explicitly connected this method to Chinese philosophy, describing qi as “life’s motion, animation. A cosmic spirit that vitalises all things and gives life and growth to nature, movement to water and energy to man.” This Eastern framework transforms the flowing hair in Antichrist into a visualisation of universal creative force. His concept of “brush motion” as “the abstract emotional key to the concrete quintessential forms” explains how these marks serve both formal and spiritual purposes. The “living line”, described as expressing “emotion and impulse”, becomes a visible expression of creative energy itself. Orlik’s method represents “a synthesis of the concrete and the abstract” in which the artist must “fill himself with that energy, so that in a moment of inspiration he may become the vehicle for its expression.”

6.

Study for Antichrist – Male, c. 1971-1973

Pencil and watercolour

With artist’s stamp lower right 35 x 84; 13¾ x 33½in.

Provenance

Private UK Collection

Exhibited

Marlborough, Winsor Birch, Cosmos of Dreams: Part II, 23 August – 17 September 2024

“… somewhere in sands of the desert

A shape with lion body and the head of a man, A gaze blank and pitiless as the sun, Is moving its slow thighs ...”

– William Butler Yeats, ‘The Second Coming’

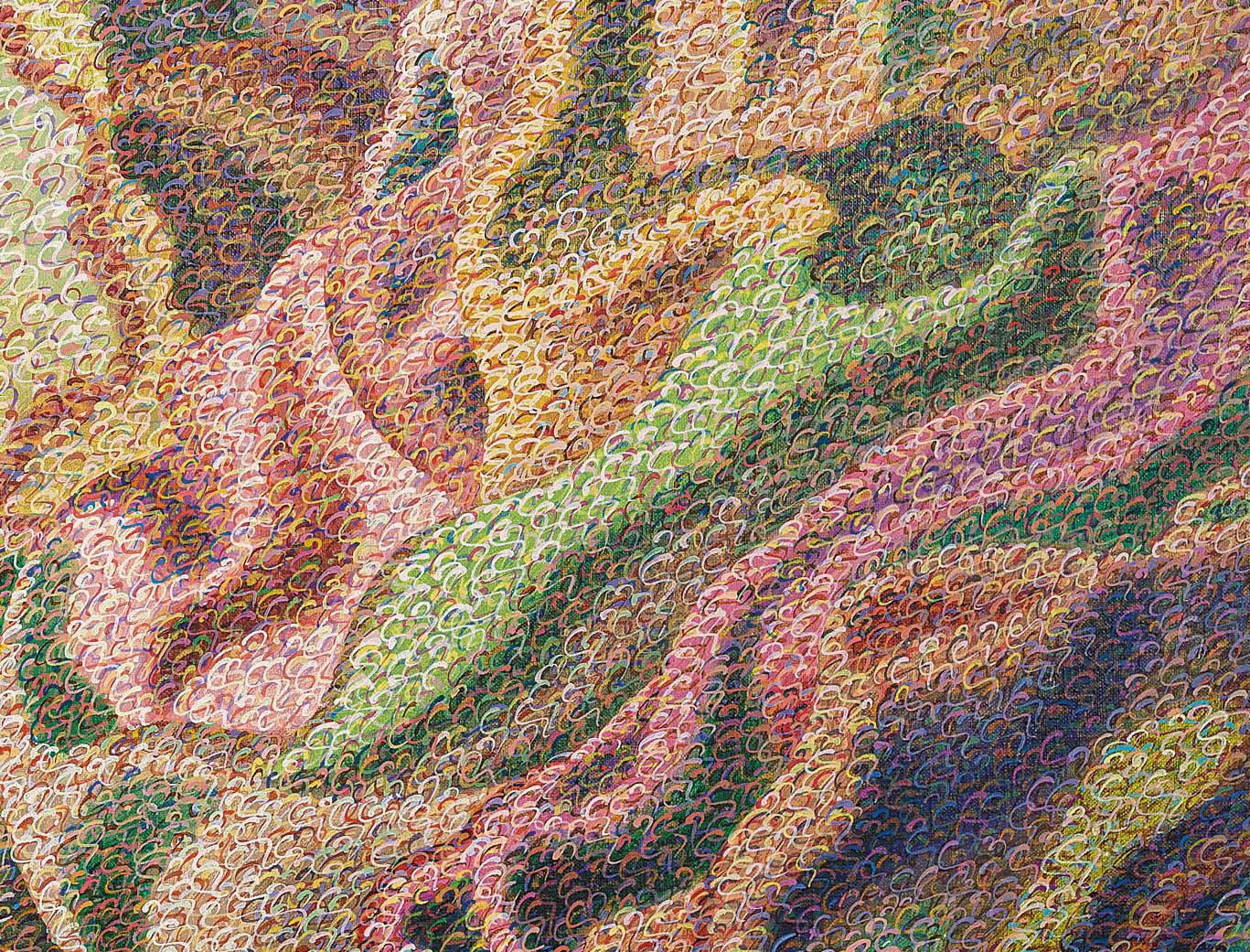

The initial preparatory drawing shows the female figure in a state of sovereign autonomy. Reclining in a classical, but open-legged, pose, she commands rather than submits; her pregnancy-implied fullness signifies her role as creator. While evoking Ingres’s Grande Odalisque (1814, Louvre), Orlik’s composition completely reverses the traditional power dynamic. Where Ingres portrays the female as an exotic object for masculine consumption, Orlik’s figure embodies the creative process itself. The hair appears as an independent force, a dark river of energy flowing across the composition with its own vitality. This anatomical detail, qi made visible, presents the feminine principle guiding creative processes.

The second study depicts the male figure in a state of complete vulnerability, crawling on hands and knees in reverent and eager anticipation. His muscular form highlights both strength and surrender, implying that masculine power finds its true purpose only in service to the greater creative force embodied by the feminine. The partial view of flowing hair creates the visual link that will unite these figures in the final work.

In the finished painting, the hair that initially appeared as an independent element now acts as a literal bridge between the figures. Set against rolling hills rendered in Orlik’s distinctive palette, the dark form above, extending from the female figure’s hair, dominates the scene like a benevolent storm bringing lifegiving rain. This creates a visual echo between the macrocosm and microcosm: the creative act mirrors cosmic forces of creation. The composition combines the individual studies into a unified statement. The female figure maintains her commanding stance, while the male figure, still approaching, is clearly drawn forward by the compelling force of her hair. Through this connection, she literally pulls him into creative participation while embodying the spiritual force that draws all masculine energy towards its generative purpose.

The title Antichrist initially implies opposition or false divinity, yet Orlik’s composition offers a very different theological perspective. The alternative reading “Annachrist” holds deep significance: “Anna” means “grace” in Christian tradition, and Saint Anne, mother of the Virgin Mary, signifies the feminine lineage through which divine incarnation becomes possible. This interpretation shifts the composition from potential blasphemy to a profound theological statement. The female figure becomes not a temptress but an announcer of grace; her hair, stretching across the landscape, becomes a visible symbol of divine feminine agency. The male figure’s willing approach suggests recognition of this authority; he is called to his proper role as a participant rather than an instigator of divine creation. This reading aligns with contemporary feminist theology, which aims to reclaim the divine feminine as central to creation narratives. Orlik’s visual theology suggests that traditional patriarchal interpretations have misinterpreted the essential nature of the creative force, confusing effect for cause and participant for director.

“People seem to cling together for comfort and protection.”

– Henry Orlik, 1972

Recently uncovered biographical documents reveal the traumatic experiences that shaped both the artist and his work. Orlik’s mother, Lucyna, survived Nazi forced labour in Belarus; his father, Jozef, endured harsh treatment before serving with Allied forces. Their meeting at a “moated castle” near Ankum, where Henry was born, transforms his origins into a mythic story of creation emerging from destruction. The family’s displacement through Polish resettlement camps established themes of renewal and resilience. Most notably, Lucyna’s steadfast presence throughout Orlik’s career, advocating for his educational choices and sending money and encouragement during difficult years in New York, embodies the nurturing creative wisdom depicted in Antichrist.

Orlik’s lifelong pursuit to “understand the world and himself through his art,” coupled with his statement that “the paintings taught me, and I was there to learn,” frames artistic creation as a receptive spiritual journey. This biographical context shifts the flowing hair from an erotic symbol to a representation of invisible connections that support creative life across distance and challenge. Orlik’s integration of scientific and spiritual understanding forecasts contemporary shifts towards holistic inquiry. The quantum-inspired technique anticipates artists like Wolfgang Tillmans, whose photographs explore core questions about matter and energy, and Anselm Kiefer’s use of material substances and mythological references. However, where Kiefer’s focus remains mainly masculine and Germanic, Orlik prioritises feminine creative agency. His 1985 statement reveals that each spiral mark signifies meditation on atomic excitation states, the fundamental energy conditions enabling all dynamic processes. This grounding in quantum physics transforms mark-making into a visualisation of creative principles operating at every scale from atomic to cosmic.

His description of treating “each shape as if it were a world in itself” to “affirm its existence even to the invisible depth of its microscopic agitation of atoms” suggests that artistic creation engages with the same forces governing physical reality. The technique’s “sensitivity of a lie-detector”, requiring genuine emotional states, validates the work’s deep personal significance.

The tragic loss of Orlik’s later works following the seizure of his London flat makes surviving pieces like Antichrist particularly precious as testimonies to his revolutionary vision. His claim that “you cannot fully understand my art without those paintings” invests these works with greater significance. The Antichrist anticipates many contemporary issues, including ecological awareness, feminist spirituality, and interdisciplinary approaches to creativity. The work’s exploration of gender dynamics offers profound insights into collaborative creativity, honouring both feminine and masculine contributions while acknowledging the primacy of feminine contributions in creative origin.

Henry Orlik’s Antichrist offers a revolutionary reimagining of creation stories, emerging from experiences of destruction and renewal. The work’s key insight, that feminine energy leads rather than simply serves masculine creative power, reflects the artist’s experience of maternal support, allowing genuine expression against patriarchal dominance. The “Annachrist” interpretation becomes a recognition of the work’s theological message: grace appears through creative survival, through love’s persistence despite systematic attempts at annihilation, and through maternal wisdom preserving life force across generations of trauma. Orlik’s blend of quantum physics, Eastern philosophy, and personal experience creates an artistic language that addresses modern concerns about holistic creativity.

In the flowing hair connecting his figures, Orlik visualises the fundamental force drawing all reality into a creative relationship despite attempts at separation. Art enthusiast Gerald Dowden’s 1978 encounter with Orlik’s work offers invaluable contemporary testimony. His immediate recognition of hair’s significance in Orlik’s iconic The Parting, describing “convoluted tresses of faded gold” and “meticulous, calligraphic care”, validates our interpretation of hair as a creative force. This is not the Antichrist of destruction but the Annachrist of generation, the divine feminine announcement that creation continues, love persists, and new life emerges from ruins. His work offers both inspiration and guidance for understanding creativity as a form of resistance, healing, and hope in an era grappling with collective trauma and spiritual disconnection.

Antichrist, c. 1971-1973

With artist’s stamp verso Acrylic on canvas

58 x 183cm.; 23 x 72in Private UK Collection

7.

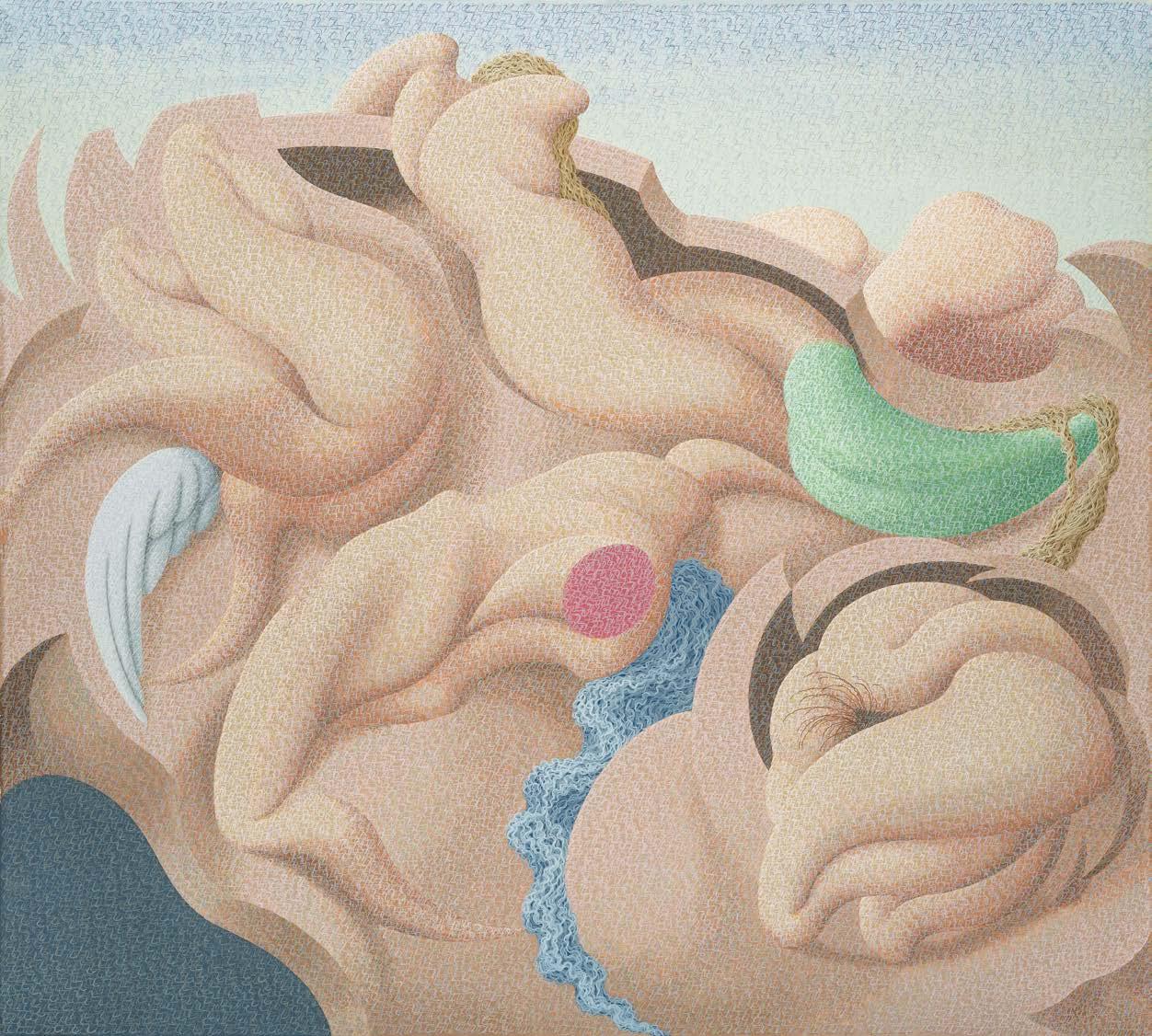

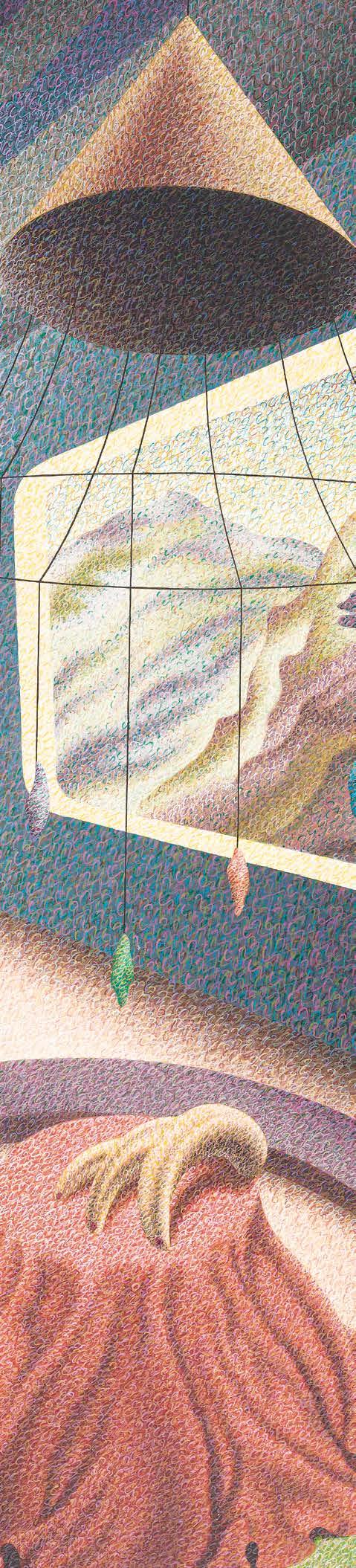

Eggs Unhatched on the Sun, c. 1970-1975

With artist’s stamp lower left Coloured crayon

78.5 x 147.5cm.; 31 x 58in.

Provenance

Museum & Art Swindon

Eggs Unhatched on the Sun is a meditation on potentiality, time, and cosmic order, staged through a visual paradox that unsettles the viewer’s sense of reality. At its heart lies a philosophical question: can creation exist where fulfilment is impossible? Orlik deploys the modest medium of coloured crayon to render an image that belongs firmly within the surrealist discourse yet retains a distinctive philosophical tenor.

In the foreground, an undulating terrain of terracotta depressions gently cradles ovoid forms. These cavities resemble both womb and tomb, symbols of creation and burial, protection and confinement. The eggs, painted in shades from ivory to blue-grey-green, suggest fragile embryos poised between possibility and impossibility. Above, a radiant golden disc presides: the sun, giver and destroyer of life, its brilliance necessary for growth yet lethal to embryonic fragility. This contrast between the earthy tones below and the ethereal upper expanse enacts the ancient divide between terrestrial and celestial realms.

Though the work announces Eggs Unhatched, some eggs appear already fractured, confounding chronology and perception. Like Dalí’s explorations of temporal fluidity, Orlik here dramatises the instability of fact and appearance. The rhythmic repetition of the egg-bearing hollows recalls Max Ernst’s Forest and Dove (1927, Tate, London), where endless vertical forms create hypnotic rhythm and existential unease, yet, whereas Ernst’s vertical repetitions yearned towards ascendence, Orlik’s horizontal expanse suggests infinite regress. The viewer becomes both witness and participant in a cosmic process that refuses completion.

Orlik’s debt to Magritte is clear in his play between title and image, exposing the gap between language and reality. The influence of Leonor Fini is likewise present in the liminal tension between life and death, transformation and suspension. Fini’s art often explored metamorphosis and dissolved boundaries, and Orlik echoes this in his fractured eggs, forms poised between becoming and dissolution. The eggs, never fully realised yet never nullified, embody a perpetual present, heavy with expectation.

Philosophical resonance runs throughout. Aristotle’s distinction between potential and actual being is translated into fragile embryonic shells; the Chinese concept of qi, vital energy coursing between earth and sky feels palpable in the shimmering interplay of tones. Mythic resonances also surface: the cosmic egg of Orphic and Hindu traditions is evoked yet subverted, its destiny thwarted beneath the hostile sun. The work reflects on genesis denied, creation foreclosed by cosmic circumstance.

The materiality of crayon is crucial. Its waxy surface seems to generate light from within, as though the eggs themselves emit the energy of their possible transformation. This surface quality aligns with surrealist interests in chance and automatism, though Orlik’s careful structure suggests deliberate orchestration.

His undulating landscape recalls Yves Tanguy’s dreamlike terrains, yet retains an optimism absent from Tanguy’s desolate visions: despite their predicament, the eggs radiate a latent energy, as if change hovers just beyond reach.

Orlik also engages with scientific consciousness. By the mid-twentieth century, radiation was understood as both nourishing and destructive; the eggs thus exist in a quantum state, simultaneously viable and doomed until observation collapses their possibilities. This scientific paradox dovetails with the philosophical one at the heart of the work.

Eggs Unhatched on the Sun resists resolution. Instead, it presents a visual koan: creation arrested, possibility thwarted yet never extinguished. Its lasting force lies in its refusal to close meaning, compelling viewers instead to dwell upon the paradox of life poised eternally between becoming and non-being. Orlik transforms the familiar into the strange, opening a field of contemplative wonder that ensures the work’s enduring power within twentieth-century surrealism.

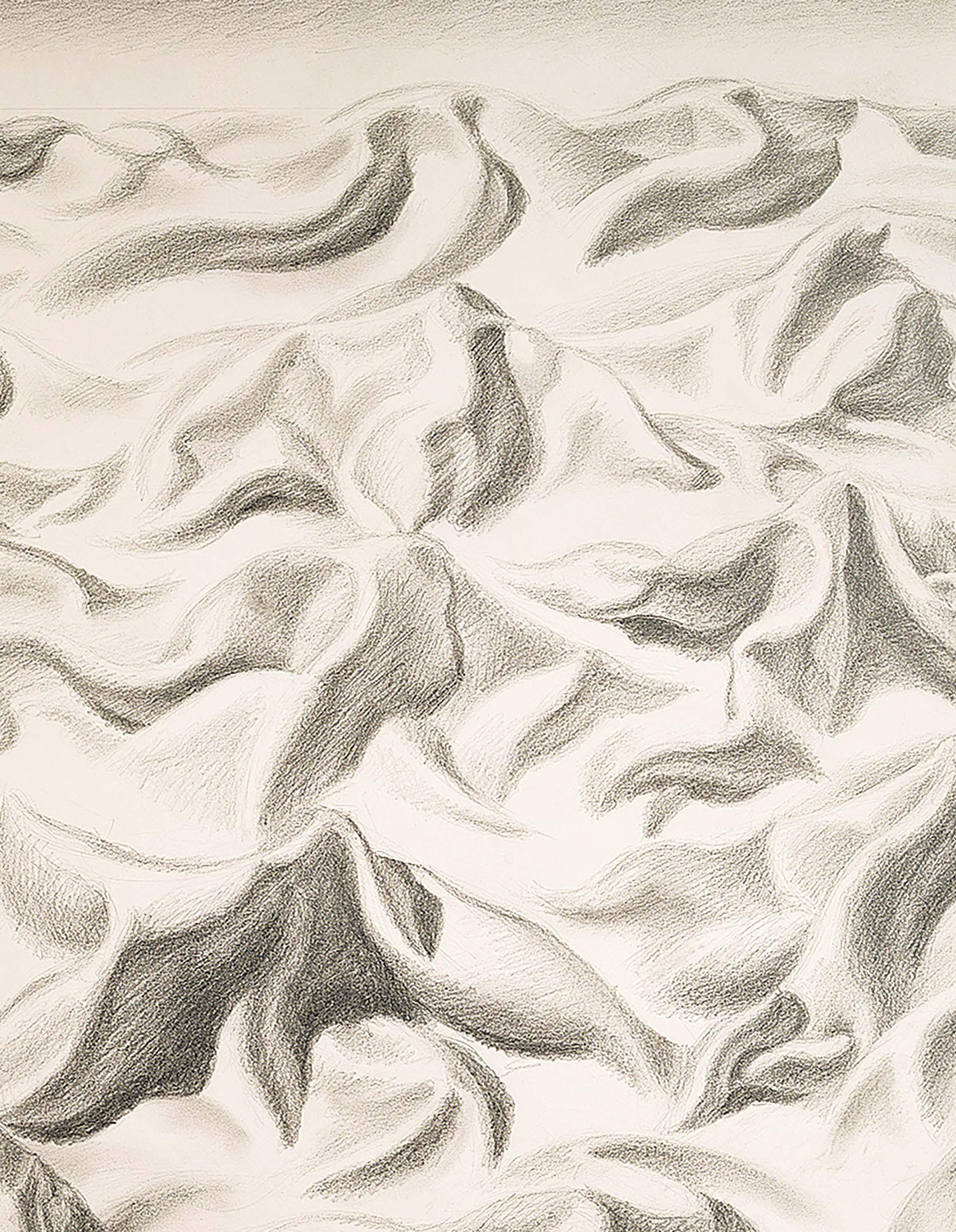

8.

Wind (Lovers Entwined), c. 1970-1972

With artist’s stamp lower right

Pencil

59 x 42.5cm.; 23¼ x 16¾in.

Provenance

Private UK Collection

Exhibited London, Winsor Birch at the Maas Gallery, Cosmos of Dreams, 9-20 August 2024

Henry Orlik’s drawing Wind (Lovers Entwined) presents three female figures entwined with exquisite tenderness, their forms rendered through precise draughtsmanship, yet their faces veiled by cascading hair. This concealment transforms what might otherwise appear a traditional nude study into an exploration of psychological complexity: intimacy is shown, yet identity withheld. Vulnerability and strength coexist.

Their flowing hair functions both as ornament and defence unlike the classical drapery of antiquity or the decorative veils of Ingres, Orlik deploys concealment strategically. These women remain visible enough to affirm beauty and dignity, yet anonymous enough to resist objectification. The motif resonates with the experience of displaced communities, where survival often required being simultaneously present and invisible.

Orlik’s mother Lucyna survived Nazi labour camps before negotiating refugee life in Britain, where selective visibility was a means of survival. Within the drawing, the central figure echoes this maternal wisdom. Her body serves as an axis around which the others find protection, her posture bearing the weight of responsibility, her obscured face preserving psychological autonomy.

The work gains further resonance when set beside Egon Schiele’s Two Women Embracing (1915, Albertina, Vienna). Both artists examine female intimacy through line, yet their purposes diverge. Schiele’s Expressionist distortion externalises crisis and vulnerability; Orlik retains classical proportion, using concealment not as exposure but as a shield. Where Schiele’s women embody individual turmoil, Orlik’s figures embody solidarity and collective survival.

Equally striking is Orlik’s treatment of atmosphere, using confident graphite shading transforming space into a tangible force that creates pressure that renders the women’s defensive configurations physically necessary. This anticipates later developments in environmental art, marking a departure from the academic isolation of figures on neutral grounds still prevalent in Britain at the time.

In the cultural landscape of 1970–71, this emphasis on feminine solidarity carried particular significance. While feminist discourse was beginning to reshape artistic thought, most visual representations continued to isolate women as singular subjects. Against the backdrop of Pop Art’s consumerist imagery and Minimalism’s industrial forms, Orlik’s insistence on intimate, human connections were both radical and humane.

“In all chaos there is a cosmos, in all disorder a secret order.”

– Carl Jung (1875-1961)

Bodies are disclosed but faces remain veiled; individual identity recedes even as nurturing presence is celebrated. A subtle balance of revelation and concealment is achieved. These figures function as archetypes of care and endurance while retaining the right to remain unknowable. In doing so, Orlik highlights the invisible emotional labour historically performed by women, especially within displaced families, where maternal strength often sustains collective survival at the cost of personal recognition.

This intimacy demands reciprocal respect from viewers. The drawing is not monumental but private, requiring close engagement. Like the concealed figures themselves, it invites trust while enforcing boundaries. Such themes of concealment and revelation, as well as highlighting the external pressures that shape intimate bonds would later shape Orlik’s career.

The contemporary relevance of Wind (Lovers Entwined) is still striking in today’s climate of digital surveillance and enforced visibility. Orlik’s recognition that genuine connection sometimes depends on strategic concealment remains profoundly resonant. The figures’ cascading hair is ultimately more than modesty. It is instead a sanctuary within exposure, affirming that intimacy requires both openness and protected distance. Through this early work, Orlik demonstrates an enduring truth: that the deepest respect for others involves celebrating what is revealed while honouring what must remain hidden.

9.

Win or Lose, c. 1975-1978

With artist’s stamp verso

Acrylic on canvas

101.5 x 76cm.; 40 x 30in.

Provenance

Private UK Collection

Exhibited London, Winsor Birch at the Maas Gallery, Cosmos of Dreams, 9-20 August 2024

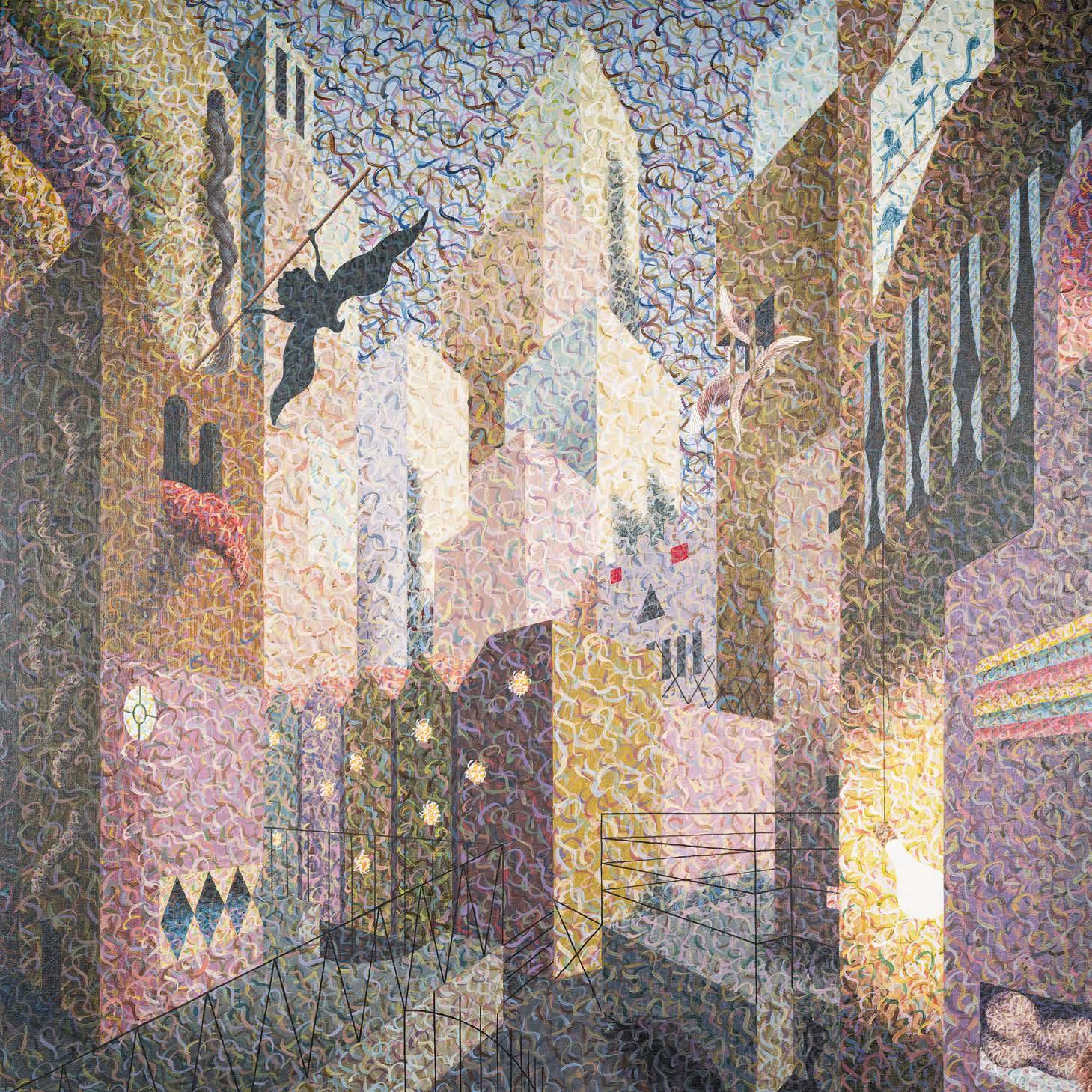

Having exhibited in Acoris’s Surrealist Masters alongside Dalí and Magritte in 1973 and 1974, Orlik went on to paint Win or Lose. The painting unfolds as a theatre of chance. On the right, a colossal stack of playing cards rises like a ziggurat, monumentalising risk itself. These are no longer recreational objects but cosmic dice, recalling Tarot towers as symbols of sudden change and divine intervention. The title, Win or Lose, affirms life’s fundamental condition as a wager in which uncertainty is the only certainty.

At the centre, a rose-hued arch is evocative of Pompeian fresco and Islamic ornament and frames a grotto where blue-green waters gather with heartshaped petals drifting above. This impossible flow recalls Escher’s paradoxes, yet where Escher pursued mathematical puzzles, Orlik attains emotional ascendance. The petals trace trajectories of negative curvature, anticipating hyperbolic geometry. Love itself appears to generate its own gravitational field, bending reality around centres of emotion rather than mass.

Above, palm-like forms emerge as crossed architectural columns, bound by Orlik’s signature “hair”, presenting delicate filaments akin to neural pathways. These fabricated palms recall Roman emblems of triumph and the Christian cross, yet here they are reconstituted as infrastructure. Triumph is not awarded by fortune but constructed deliberately, a cultural response to existential uncertainty.

To the right, a lattice interrupts the surface, recalling Mondrian’s grids and Le Corbusier’s Modulor, yet its function is enigmatic: an attempt to measure the unmeasurable. Above, chimneys crown a monumental building. Their verticality contrasts with the composition’s horizontal drift, conjuring both domestic shelter and industrial memory. In the 1970s, such imagery resonated strongly, balancing the security of post-war reconstruction with an emerging awareness of environmental cost.

Every inch of the canvas pulses with Orlik’s horror vacui. Unlike the medieval dread of emptiness, his mark-making stems from a quantum conviction that space is not void but energy in excitation. Orlik uses such excitations to create luminous yet muted tones in what he called “chromatic vibrations.” His writings describe human “optical awareness of the chromatic vibrations of sources of light,” and here colour behaves as energy rather than ornament. Blues breathe with microscopic intensity; rose and yellow imbue architecture with warmth; petals glow as if lit from within by emotional charge. The twilight tonality captures a liminal hour, when rational outlines dissolve into possibility.

The playing cards convert the scene into a cosmic casino where stakes exceed material gain: can consciousness actively shape reality, or is it bound to react to circumstance? The petals embody love as paradox: connection entails loss, intimacy trades independence, meaning sacrifices certainty. Yet Orlik shows that such wagers generate their own physics, suspending conventional rules within zones of heightened commitment. The fabricated palms extend this vision, representing culture’s effort to build triumph from fragile material, asserting that meaning must be constructed rather than received. Since the binary of winning and losing is inescapable, wisdom lies in choosing contests wisely and fashioning frameworks that sustain future victories even when present battles are lost.

The painting explores the paradox of modern consciousness: how unstable forces become the foundation stones of meaning, and how the growing capacity to measure the world coexists with awareness that essential experiences resist calculation. The grid, both blueprint and trap, symbolises this tension, a visual recognition that even the most advanced systems remain crude approximations of lived complexity.

The central arch evokes sanctuaries across traditions; the palms combine crucifixion and triumph; chimneys rise like secular incense. Orlik secularises sacred forms without draining their spiritual force, suggesting that transcendence arises not from doctrine but from engagement with uncertainty.

Born in Germany to a Belarusian mother conscripted into labour and a Polish father who served with the Allies, Orlik grew up acutely aware of identity as contingent and unstable. The cards evoke the refugee experience, where bureaucratic decisions determined fates across generations. The chimneys symbolise both promise and alienation for post-war immigrants, embodying prosperity tempered by estrangement from tradition. His filaments of hair stand for the fragile networks, letters, remittances, and memories that held dispersed communities together.

The painting situates itself between Piranesi’s impossible prisons, Klee’s architectural fantasies, and Bosch’s moral theatres. Yet where Piranesi conveys confinement, Orlik finds liberation through uncertainty; where Klee adopted playful primitivism, Orlik imagines consciousness as constructive force; where Bosch moralised, Orlik proposes collaboration with chance on quantum terms. The monumental cards also anticipate shifts within the art world itself, foretelling a system increasingly governed by speculation, closer to casino logic than aesthetic judgment. Against this volatility, the floating petals suggest an alternative physics: that genuine emotion and craft can defy market gravity, sustaining meaning through patience and care.

Through cards, grid, petals, chimneys, and palms, Orlik makes visible that every decision, relationship, and creative act is a wager. Its radical insight is not to escape the game but to inhabit it creatively. The cards stand as monuments to uncertainty; the petals demonstrate that love alters physics; the grid records the effort to measure impossibility; the chimneys exhale the persistence of ordinary striving; the palms transform triumph into infrastructure. Each spiralling mark is a victory over entropy, an architecture of resilience.

In an era of algorithmic prediction, Orlik’s vision is freshly urgent. Probability may structure scientific knowledge, yet human meaning persists beyond calculation. Win or Lose offers an ethic of creative wager, insisting that consciousness remains the true architect of significance.

10.

Change: Celtic Symbol, c. 1975-80

Mixed media on card

67 x 82cm.; 26¼ x 32¼in.

Provenance

Private UK Collection

Exhibited

Marlborough, Winsor Birch, Cosmos of Dreams: Part II, 23 August – 17 September 2024

Change: Celtic Symbol is a study of the futility of territorial conflict, exposing the fragility of boundaries that attempt to divide peoples bound by shared heritage. The work transforms the ancient Wessex landscape into a mythological stage where illusionary lines on maps confront deeper evolutionary and cultural continuities.

The Orlik family’s resettlement in Wiltshire placed the artist in direct contact with the prehistoric landscapes of Stonehenge and Avebury. These formative encounters, alongside repeated journeys through the Wessex countryside, endowed him with a vision of landscape as palimpsest: both everyday terrain and archaeological revelation.

At the centre of Change: Celtic Symbol lies a wall that embodies the universal concept of division. Constructed from arches, steps, and geometric forms, it does not represent a specific fortification but rather the symbolic and anthropological impulse to create separation. Orlik described it as “a language written in a language that neither would ever understand,” an enigmatic script that obscures communication while purporting to enable it. Meandering across the canvas like a river, the wall emphasises arbitrariness; low in height, it is less a defensive obstacle than a ritual marker of “divisive division.”

Two female figures dominate the scene, positioned in mirrored stances across this barrier. Their resemblance undermines the rationale for conflict, revealing confrontation as projection rather than necessity. Their raised curved weapons, resembling both tusks and antler-tools, connect present antagonism with prehistoric traditions, recalling the excavation implements used to shape earthworks at Avebury. The struggle thus becomes not only territorial but cosmological: over who claims the right to shape the land itself.

Beneath them unfolds a “living landscape,” its undulating green terrain recalling burial mounds and organic forms. Orlik discerned, within these rhythms, a reclining female figure, suggesting the earth’s embodiment as both witness and participant in human history. This imagery resonates with the Celtic Cailleach, the divine hag who shapes mountains and valleys, reminding us that human conflict remains transient upon the enduring body of the land. Colour too, reinforces the symbolic charge. Greens, signifying in Celtic tradition the otherworld, situate the scene within liminal space, while russet tones recall ancient weapons and organic decay. The spectral flesh of the figures appears almost as emanations of the land itself.

Change: Celtic Symbol, embodying Orlik’s lifelong pursuit of unity between myth, science, and history, preserves cultural memory while offering prophetic insight into nationalism, migration, and identity. The figures remain locked in mirrored opposition; the wall meanders through their world; the green mounds pulse with accumulated life. Yet beneath these divisions lies a deeper recognition: enemies often share the closest kinship, and the boundaries we defend may prove less enduring than the connections they deny.

“Imagine a fairy chain stretched from mountain peak to mountain peak, as far as the eye could reach, and paid out until it touched the “high places” of the earth at a number of ridges, banks, and knowls.”

–

Alfred Watkins, The Old Straight Track

Lost and Remembered, c. 1972

With artist’s stamp verso

Acrylic on canvas

74 x 109cm.; 29 x 43.5in.

Provenance

Private UK Collection

Henry Orlik painted Lost and Remembered in 1972 during his five-week-stay in Warsaw as part of an extended visit to Poland when he fully explored the country. He found an apartment in the district which housed the embassies and recalls “living like a king”, quaffing Russian champagne and wandering through the city. He remembers the strangeness of the newly rebuilt centre after the war, which felt “not quite real”, like a film set juxtaposed with buildings that were still pockmarked with bullet holes.

Dominating Lost and Remembered, a coral-pink, shell-like form, its spiral cavity evoking the mathematical precision of organic growth, rises onto its “knees”, inching forward. Orlik describes it as a “very feminine” shape. Vagina-like, its form appears both as an amphitheatre and sanctuary, recalling natural formations: caves, shells, water-carved stones that seem intentional yet are entirely the result of elemental forces. It is both enticing and threatening and we encounter a world where the earth reveals its creative essence through timeless forms replicated in multiple manifestations.

The cavernous shell looms towards a small, luminous pearl-like sphere, sandy in texture yet radiant, as though distilled from geological time. It embodies transformation: sand, water, and pressure crystallised into precious form. A small, unformed fleshy creature, maybe sperm or phallus, inches towards the cavern and reinforces the temporal scale. With patient determination, it embodies rhythms beyond human urgency, echoing John Keats’s insight in Ode to a Nightingale (1819): that true understanding requires surrender to natural time. Its movement is as easy and instinctive as a child chasing a ball. Here, reverence is not imposed by doctrine but expressed by nature itself, the creature is compelled towards the round sphere and approaches its beauty with instinctive care, unaware of the lurking red cavern. The juxtaposition of the flesh-creature, sphere, and monumental spiral establishes a poetic dialogue between scales, microscopic life and geological vastness that are united by patterns of growth and transformation.

Out of this landscape to the left, human bodies intertwine and elongate, appear and dissolve, creating a ring of infinite creation. Orlik’s vibrating brushwork animates these organic, morphous forms that ripple with subtle energy as if being absorbed into matter. The motif recalls Ovid’s Metamorphoses, where human bodies transmute into natural features, or Joan Miró’s The Birth of the World (1925, Museum of Modern Art, New York), where elemental chaos erupts into being. Yet Orlik’s tone is gentler, suggesting alluring absorption rather than violence: humanity here becomes part of the landscape’s memory rather than its master.

Lost and Remembered carries more than one truth and within his erotic landscape imagery Orlik plays with concepts of loss of innocence, involuntary encounters, unsolicited desire and enticement, the terror of childhood, of loss and love, the creative or generative urge despite external dangers, the breaking 11.

“All is flux, nothing stays still.”

– Heraclitus

up of community or family. He discloses, what Blake would call, ‘contraries’, such that destruction leads to creation, for if the small figure reveals itself as an unformed phallus or sperm chasing the enticing pearl/egg into the vagina/ cavern, it destroys the homogeny and safety of the ring of warm bodies but thus provokes a different creation within the red chamber. Similarly, the encounter may be viewed as loss of innocence at the hands of experience: the small unformed creature naively chases its ball in a childhood game, lured into the enticing mouth of the experienced, waiting red creature, and it becomes its prey. A figure behind it, cowers and turns away, knowing but unwilling to witness the devastating, life-altering encounter.

In the sky, an umbrella-shaped, multi-faceted star or rent in the atmosphere connects to the centre of the ring of figures by a delicate, thin antenna or aerial. The human figures lie in the green shadow of this portal/star, as if it is integral to them but as Orlik states, “it has a drive of its own.” Its form resembles a tendril or climbing plant and seems to symbolise the earth’s own communicative capacity: a reaching gesture beyond its immediate boundaries suggesting a planetary connection beyond the authority of humans who shelter in its shadow.

The coral-pink of the shell-like form radiates warmth and vitality, set against supporting greens of growth, sandy golds of sediment, and muted blues of water and air. These are the colours of the planet itself; stone, vegetation, sea, and sky, presented in their essential state, beyond interpretation or possession. Spatially the work departs from naturalistic perspective. Forms inhabit a realm governed by psychological and spiritual logic, where relationships express meaning rather than optical realism. In this sense, the title Lost and Remembered becomes clear. It does not refer to individual memory but to the earth’s own remembrance: the shell embodying spiral growth, the pearl recording transformation under pressure, the antenna symbolising universal connectivity. Orlik presents the landscape as an archive of enduring patterns.

The resonance of this vision is acute in an era of ecological crisis. Unlike apocalyptic visions of desolation, Lost and Remembered affirms resilience. Robinson Jeffers, in The Answer (1937), urged “falling in love outward” with nature beyond human concerns. Orlik anticipates such thinking, positioning beauty not as a human imposition but as a property of the earth itself. His work parallels aspects of Land Art, Andy Goldsworthy’s ephemeral sculptures, for example, which highlight natural processes with minimal intervention. Yet while Goldsworthy foregrounds temporality, Orlik presents a timeless cosmos where creativity is constant. The painting is set within a curved landscape: the curvature of the Earth itself. This indicates the universality of the depiction which is not particular to any one person or even species but can have both microscopic focus – to the smallest atom – and macroscopic. It, thus, reveals the universality of the process of creation and that desire (as creative urge) is a concept that is found in the smallest quantum and replicated in all aspects of the universe. It is unavoidable, inevitable and all-encompassing. Orlik’s vision affirms the earth’s innate, enticing, creativity rather than its destructive indifference.

Born in post-war Germany to Polish and Belarusian parents displaced by conflict, Orlik understood loss and impermanence intimately. For him, the world’s fundamental patterns seen in the spiral, the pearl, the small creature, offered consolation: beauty more enduring than the social and political upheavals that defined his childhood. In this sense, the work meditates on survival: what remains when nations dissolve, when empires fall, when memory itself falters.

Thomas Hardy’s Return of the Native (1878) and Alan Weisman’s The World Without Us (2007) both suggest that imagining life without humanity sharpens our perception of what truly matters. Similarly, Albert Bierstadt’s Among the Sierra Nevada, California (1868, Smithsonian American Art Museum, Washington, D.C.) dwarfs human figures against vast landscapes, though Orlik’s vision feels more intimate, attending to the earth’s inner mechanisms rather than its grandeur. Where Bierstadt emphasises scale, Orlik attends to process, the transformations that continually generate beauty.

Orlik painted two version of Lost and Remembered. This is the second, larger version in which he added, on the right edge, a curved, sharp structure with angular sharp, cutting, plains. It blurs boundaries between geological formation and cultural ruin, and its cutting edges expose the fragile susceptibility of the naked organic forms. The hidden construction lends an additional, lurking threat. Orlik states: “that’s life, you’re always in danger” and here poses the ambiguity between what is natural and what is man-made threat. It is non-biological and menacing, cold and machine-like, destructive and inhumane and diametrically opposed to the distant star/portal, its harsh outline appears as an oppositional threat to the cosmic, but remote shape. Its mechanised quality emphasises the vulnerability of the soft, fleshy ring of figures and offers the idea of the destructive indifference of unasked for existence which is at the whim of forces beyond the control of the human.

Lost and Remembered functions both as elegy and celebration, mourning what human activity has disrupted while affirming nature’s inexhaustible creativity. Every form in the painting from the spiral cavity, the luminous pearl, the innocent creature, the dissolving torsos, the machine-like ruins, participates in a wider meditation on memory and endurance. Consciousness itself, Orlik suggests, may be nothing more than the earth’s way of momentarily recognising its own magnificence.

12.

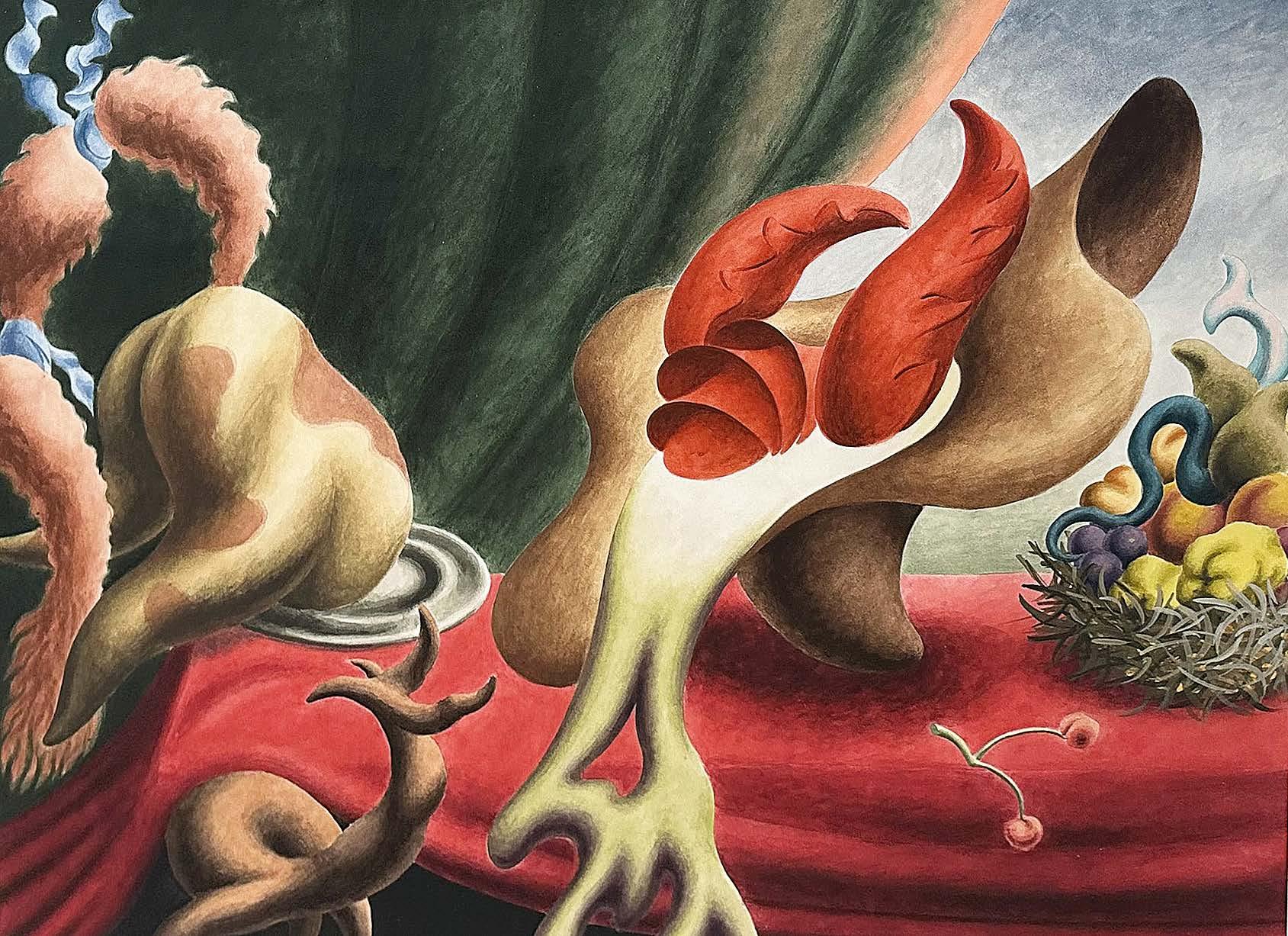

Surrealist Still Life, c. 1970

Watercolour

51 x 68.5cm.; 20.1 x 27in.

Provenance

Private UK Collection

“I’m always searching for my inner self. But I don’t know if I’m successful. You never understand the creative process.”

– Henry Orlik

In Henry Orlik’s Surrealist Still Life, what starts as a familiar scene of household objects transforms into a disturbing stage where ordinary items assume the roles of characters in an enigmatic story. This watercolour marks a pivotal moment in Orlik’s development, when his innovative visual language began forming the systematic study of consciousness that would define his mature work.

The crimson tablecloth commands attention not only as a support but as a theatrical platform. This is no burgundy dining room; rather, it is the intense scarlet of ceremony, transforming every object that rests upon its surface. The colour acts as an alchemical agent, giving familiar forms new significance and establishing the work’s premise: that consciousness is a transformative field in which meaning shifts with the focus of attention.

On the left, a pink anthropomorphic figure poses with deliberate sensuality. Adorned with flowing azure ribbons, this puppet-like form is simultaneously vulnerable and self-assured, theatrical yet intimate. Its confident stance suggests privileged knowledge, while the ribbons link disparate elements, unifying scattered objects into psychological coherence and illustrating Orlik’s view that consciousness operates through connection, not isolation.

The dark coral-coloured horns rising from the centre defy categorisation, evoking musical instrument, organic growth, threats, and sculptural form. Their warm hue resonates with the tablecloth while asserting a distinct identity, functioning as a conductor’s baton orchestrating the surrounding ensemble. Positioned between the sensual figure and symbolic elements, the horns bridge disparate realms, reflecting Orlik’s capacity to translate incompatible languages of meaning.

The anthropomorphic chicken, cradled in a gleaming silver dish, signifies Orlik’s most daring transformation. By blurring the boundary between living creature and culinary object, the work intentionally generates discomfort. Surrealism

here arises not from visual trickery, but through close attention to unsettling truths of everyday life. Its presentation suggests offering and sacrifice, feast and funeral, compelling viewers to confront the ethics of consumption.

Orlik’s most symbolically dense passage occupies the right margin, where a botanically precise crown of thorns introduces Christian iconography into dialogue with secular imagery. Enigmatically, a miniature whale’s tail creates oceanic vastness in an intimate domestic space. This evocative detail: earth’s largest creatures depicted as the composition’s smallest element, transforms the table into an oceanic depth, suggesting that consciousness navigates fluid territories where familiar landmarks lose conventional meaning. More explicitly, Orlik colludes with Caravaggio’s still life at the front of his painting Supper at Emmaus (1601, National Gallery, London) which has incongruous fish-tail shadow, signifying the revelation of Christ’s attendance at the meal. In Orlik’s painting, he transforms Caravaggio’s Christ to shamanic antlers, his chicken on its platter, and his basket becomes a crown of thorns. Whilst Caravaggio’s still life teeters on the edge of the table, Orlik’s gets up and dances. High-kicking cherries suggest temptation and sweetness, while a serpent emerges from the assemblage, animating the composition through archetypal resonance.

Orlik’s watercolour technique captures content with exceptional precision. Its transparency enables colours to interact through layers, producing atmospheric effects that reflect the fluid boundary between conscious and unconscious experience. While echoing Edward Burra’s theatrical watercolours of the 1920s and 1930s, particularly in muted yet vibrant colour harmonies, Orlik focuses on interior landscapes, using the medium’s unpredictability to access psychological domains beyond rational understanding.

The puppet figure’s theatrical pose implies selfhood as performative, while the transformed chicken challenges perceptions of subjectivity. These explorations resonate for an artist shaped by mid-twentieth-century European displacements, inheriting a nuanced sense that identity must remain adaptable. Created in the mid-1970s, as Orlik established his reputation in London following his breakthrough exhibitions at the Acoris Surrealist Art Centre, the work fuses surrealist principles with personal vision, inviting close viewing and fostering a conspiratorial relationship with the image.

The subtle erotic undertones engage surrealism’s exploration of desire, yet Orlik retains restraint, preventing symbolism from becoming literal. Surrealist Still Life explores consciousness under pressure, synthesising domestic familiarity with psychological strangeness to raise questions about identity, desire, and meaning. The work refuses resolution, instead inviting engagement with mystery and showing that familiar reality holds infinite possibilities. Through careful orchestration of transformed objects on their scarlet stage, Orlik creates genuine mystery that enriches understanding and demonstrates consciousness retains capacity for surprise despite attempts at prediction and control.

“My painting is visible images which conceal nothing,” he wrote, “they evoke mystery and, indeed, when one sees one of my pictures, one asks oneself this simple question, ‘What does it mean?’ It does not mean anything, because mystery means nothing either, it is unknowable.”

– René Magritte (1898-1967)

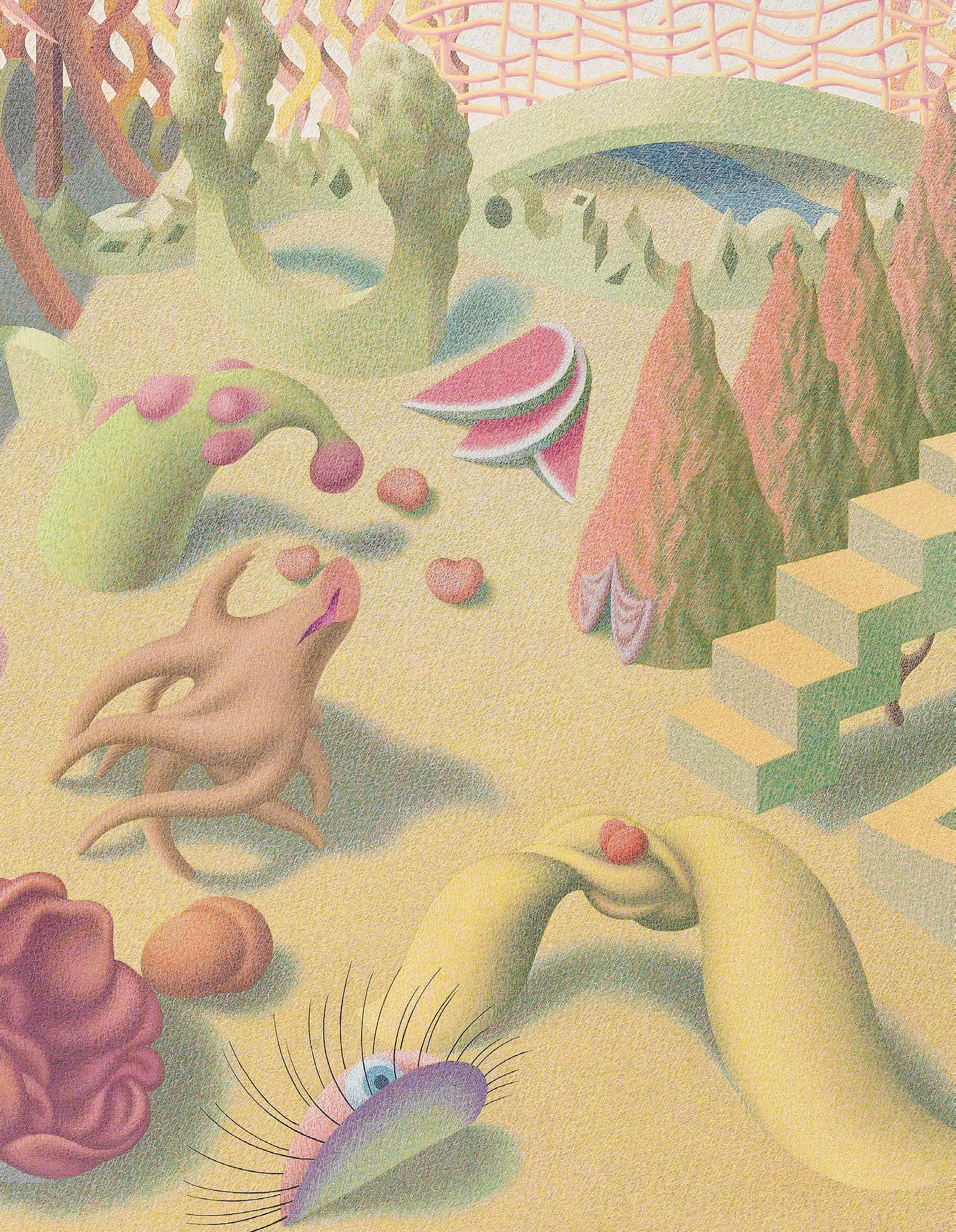

13.

Escape, c. 1970-1975

Mixed media on card

87 x 60cm.; 34¼ x 23½in.

Provenance

Private UK Collection

Exhibited

Marlborough, Winsor Birch, Cosmos of Dreams: Part II, 23 August – 17 September 2024

Henry Orlik’s Escape was created during the artist’s most celebrated period, and it showcases his refined ‘excitations’ technique: thousands of microscopic, spiralled brushstrokes that animate the surface with ‘molecular energy’. The painting depicts the creative spirit’s flight from institutional constraints toward an authentic vision.

The composition depicts a radiant yet empty world. The absence of human figures signals a state of consciousness unmediated by social expectation, recalling Giorgio de Chirico’s The Enigma of an Autumn Afternoon (1910, private collection).

However Orlik’s realm radiates optimism rather than melancholy. Across this luminous terrain, a chimaera: part bird, part sea creature, ascends alone, perhaps embodying the artist’s liberated consciousness.

Below, an Arcadian maze glows with terracotta, amber, and gold. Its intricate arches and terraces, rendered with Orlik’s distinctive brush marks, appear seductive yet entrap the viewer. Rising above is a snow-capped mountain, an insurmountable barrier that blocks escape. Together, these elements articulate the painting’s central message: conventional routes to recognition are blocked, and only extraordinary courage permits authentic creation.