WILDLIFE

LANDSCAPE

FLORA AND

BIRD WATCHING

WILDLIFE

LANDSCAPE

FLORA AND

BIRD WATCHING

Dirk Hilbers

Crossbill Guides: Iceland

First print: november 2014

Second print: march 2017

Third print: november 2025

Initiative, text and research: Dirk Hilbers

Additional research, text and information: Kim Lotterman

Editing: John Cantelo, Brian Clews, Cees Hilbers, Riet Hilbers, Niels de Haan Kim Lotterman, Gino Smeulders

Illustrations: Horst Wolter, Alex Tabak

Maps: Dirk Hilbers / mapy.com

Type and image setting: Oscar Lourens

Print: ORO grafic projectmanagement / PNB Letland

ISBN 978-94-91648-36-6

This book is made with FSC-certified paper. Instead of compensating the CO2emissions of the printing process, as we usually do when making a Crossbill Guide, we’ve chosen to invest that money in nature conservation. You can find details of the project we’re supporting on our website, under ‘Downloads’ on the Iceland guidebook page.

© 2025 Crossbill Guides Foundation, Arnhem, The Netherlands

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form by print, photocopy, microfilm or any other means without the written permission of the Crossbill Guides Foundation.

The Crossbill Guides Foundation and its authors have done their utmost to provide accurate and current information and describe only routes, trails and tracks that are safe to explore. However, things do change and readers are strongly urged to check locally for current conditions and for any changes in circumstances. Neither the Crossbill Guides Foundation nor its authors or publishers can accept responsibillity for any loss, injury or inconveniences sustained by readers as a result of the information provided in this guide.

Published by Crossbill Guides in association with KNNV Publishing.

crossbillguides.org

knnvpublishing.nl

saxifraga.nl

This guidebook is a product of the non-profit foundation Crossbill Guides. By publishing these books we want to introduce more people to the joys of Europe’s beautiful natural heritage and to increase the understanding of the ecological values that underlie conservation efforts. Most of this heritage is protected for ecological reasons and we want to provide insight into these reasons to the public at large. By doing so we hope that more people support the ideas behind nature conservation. For more information about us and our guides you can visit our website at: crossbillguides.org

Head out to one of the many bird cliffs and stand eye to eye with thousands of Puffins, Razorbills, Guillemots, Fulmars and Kittiwakes. The most impressive cliffs are on routes 4, 7, 18, 19 site A on page 172.

Book a seat on a boat and go whalewatching. (G on page 143, C on page 160 and G on page 204).

Marvel at Iceland’s rugged landscapes and its fascinating geology, full of volcanoes, weirdly shaped lava fields, hot water springs, steaming hillsides and massive waterfalls. There is no place in the world like Iceland. (e.g. routes 3, 4, 5, 7, 14, 16, 17, 23)

Head out to Mývatn – a large shallow inland lake where many rare birds breed, including Gyrfalcon, Harlequin Duck and Barrow’s Goldeneye. (route 14)

Head out to the fairytale Jökulsárlón lagoon, where hundreds of icebergs, laced with black swirls of lava, make for an unforgettable sight. (route 23)

D on’t forget about the traditional side of Iceland: visit Þingvellir (route 1), the enchanting old wooden churches and turf-roofed houses, and get carried away by Iceland’s sagas.

Go hiking in Þorsmörk, Landmannalaugar and Skaftafell, and experience Iceland on foot. (R and S on page 148 and route 21 and 22)

Head for the remote and little visited West Fjords, where small fisherman’s villages, deep fjords and flowery valleys make for a beautiful destination (routes and sites from page 161 onwards).

This guide is meant for all those who enjoy being in and learning about nature, whether you already know all about it or not. It is set up a little differently from most guides. We focus on explaining the natural and ecological features of an area rather than merely describing the site. We choose this approach because the nature of an area is more interesting, enjoyable and valuable when seen in the context of its complex relationships. The interplay of different species with each other and with their environment is astonishing. The clever tricks and gimmicks that are put to use to beat life’s challenges are as fascinating as they are countless. Take our namesake the Crossbill: at first glance it is just a big finch with an awkward bill. But there is more to the Crossbill than meets the eye. This bill is beautifully adapted for life in coniferous forests. It is used like scissors to cut open pinecones and eat the seeds that are unobtainable for other birds. In the Scandinavian countries where Pine and Spruce take up the greater part of the forests, several Crossbill species have each managed to answer two of life’s most pressing questions: how to get food and avoid direct competition. By evolving crossed bills, each differing subtly, they have secured a monopoly of the seeds produced by cones of varying sizes. So complex is this relationship that scientists are still debating exactly how many different species of Crossbill actually exist. Now this should heighten the appreciation of what at first glance was merely a plumb red bird with a beak that doesn’t close properly. Once its interrelationships are seen, nature comes alive, wherever you are.

To some, impressed by the ‘virtual’ familiarity that television has granted to the wilderness of the Amazon, the vastness of the Serengeti or the sublimity of Yellowstone, European nature may seem a puny surrogate, good merely for the casual stroll. In short, the argument seems to be that if you haven’t seen a Jaguar, Lion or Grizzly Bear, then you haven’t seen the ‘real thing’. Nonsense, of course. But where to go? And how? What is there to see? That is where this guide comes in. We describe the how, the why, the when, the where and the how come of Europe’s most beautiful areas. In clear and accessible language, we explain the nature of Iceland and refer extensively to routes where the country’s features can be observed best. We try to make Iceland come alive. We hope that we succeed.

This guidebook contains a descriptive and a practical section. The descriptive part comes first and gives you insight into the most striking and interesting natural features of the area. It provides an understanding of what you will see when you go out exploring. The descriptive part consists of a landscape section (marked with a red bar), describing the habitats, the history and the landscape in general, and of a flora and fauna section (marked with a green bar), which discusses the plants and animals that occur in the region.

The second part offers the practical information (marked with a purple bar). A series of routes (walks and car drives) are carefully selected to give you a good flavour of all the habitats, flora and fauna that Iceland has to offer. At the start of each route description, a number of icons give a quick overview of the characteristics of each route. These icons are explained in the margin of this page. The final part of the book (marked with blue squares) provides some basic tourist information and some tips on finding plants, birds and other animals.

There is no need to read the book from cover to cover. Instead, each small chapter stands on its own and refers to the routes most suitable for viewing the particular features described in it. Conversely, descriptions of each route refer to the chapters that explain more in depth the most typical features that can be seen along the way.

In the back of the guide we have included a list of all the mentioned plant and animal species, with their scientific names and translations into German and Dutch. Some species names have an asterix (*) following them. This indicates that there is no official English name for this species and that we have taken the liberty of coining one. We realise this will meet with some reservations by those who are familiar with scientific names. For the sake of readability however, we have decided to translate the scientific name, or, when this made no sense, we gave a name that best describes the species’ appearance or distribution. Please note that we do not want to claim these as the official names. We merely want to make the text easier to follow for those not familiar with scientific names. An overview of the area described in this book is given on the map on page 12. For your convenience we have also turned the inner side of the back flap into a map of the area indicating all the described routes. Descriptions in the explanatory text refer to these routes.

Icons used to charactarise the routes and to show the key interest:

Invertebrates

Additional routes and sites in the West Fjords*

Routes in Northeast Iceland and Akureyri

Route 13: Hrísey

Route 14: Lake Mývatn

Route 15: Walk from Reykjahlíð to Dimmuborgir

Route 16: Mývatn volcanic hotzone and the Dettifoss 190

Route 17: Ásbyrgi 194

Route 18: Rauðinúpur and Melrakkasletta

Additional routes and sites in Northeast Iceland*

Routes in East Iceland

Route 19: Herað valley and Borgafjörður

Route 20: Djúpivogur and Bulandsnes

Additional routes and sites in East Iceland*

Routes in Southeast Iceland

Route 21: Walking in beautiful Skaftafell

Route 22: To the snout of the Skaftafell Icecap 220

Route 23: Jökulsárlón – The Iceberg lagoon

*The names and locations of the additional sites are shown in the map in the back cover.

Iceland – who hasn’t dreamt of visiting this mythical island? The place where nature is at its most untamed. This is the country of volcanoes, lava fields, enormous waterfalls and massive icecaps. The land where the earth itself seems to be alive, blowing off steam in vents, geysers and in the foul-smelling pools of boiling mud. Beneath the dark clouds of one of the many Atlantic depressions, the multi-hued rocks have a surreal kind of beauty: blackish lava, reddish rhyolite, shiny volcanic glass, bluish magnesium stains and bright-green mosses. The desolate interior highlands contrast strongly with the coast, which is green and alive with thousands of birds and wildflowers. Iceland has indeed many faces, yet is one of a kind: rugged, wild, explosive, and achingly beautiful.

Archaic and primeval as Iceland may seem, it is geologically an infant. The land is young and born out of countless volcanic eruptions. Iceland is one of the world’s best places to see both the creative force of volcanism and the powers of erosion at work. It is also the country where you can see the effects of glacial and postglacial processes – the same ones that shaped so many parts of temperate and northern Europe at the end of the last ice ages.

The landscapes of Iceland are very photogenic. Anyone with a passion for photography will have an unforgettable time in Iceland. Not only the land flirts with the camera, but so do the birds. Due to its isolated location, Iceland has a relatively small diversity of birds, but those which do occur, do so in enormous numbers. There are thousands of Whooper Swans, hundreds of thousands of Arctic Terns and Razorbills and an estimated 2 million pairs of Puffins!

Although Iceland is a very wild place, travelling is relatively simple and convenient (with the exception of the highlands, see page 59 and 231). Today, anyone can experience the wild splendour and wildlife of this country. This book will help you to make the most out of your visit.

In this book, the Icelandic spelling of place names is used. Some signs do not occur in other languages. The Þ (as in Þingvellir) is pronounced as ‘th’ in the word ‘thing’. The LL (also as in Þingvellir) is pronounced ‘dl’ in ‘ headland’. The ð (as in Buðir) is also pronounced as ‘th’. The æ (as in Snæfellsnes) is pronounced as the ‘y’ in ‘my’. The ö (as in Þorsmörk) is pronounced as the ‘i’ in girl.

On Iceland, stunning scenery and wildlife go hand in hand. The icebergs of the scenic Jökulsárlón glacial lagoon are a favoured haulout for Common Seals (route 23).

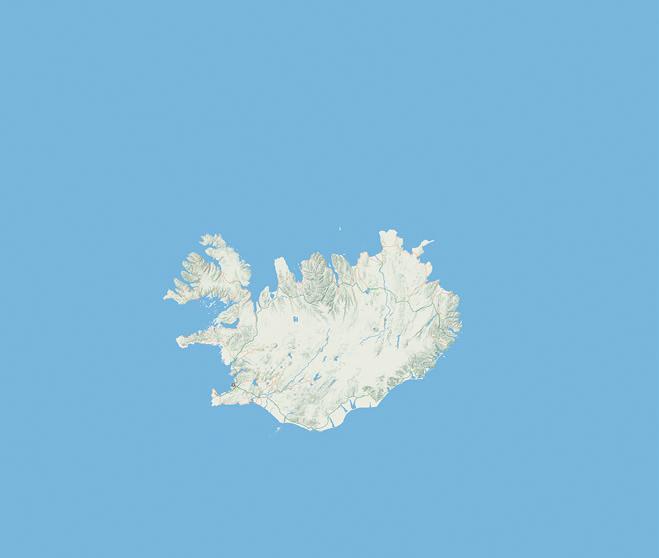

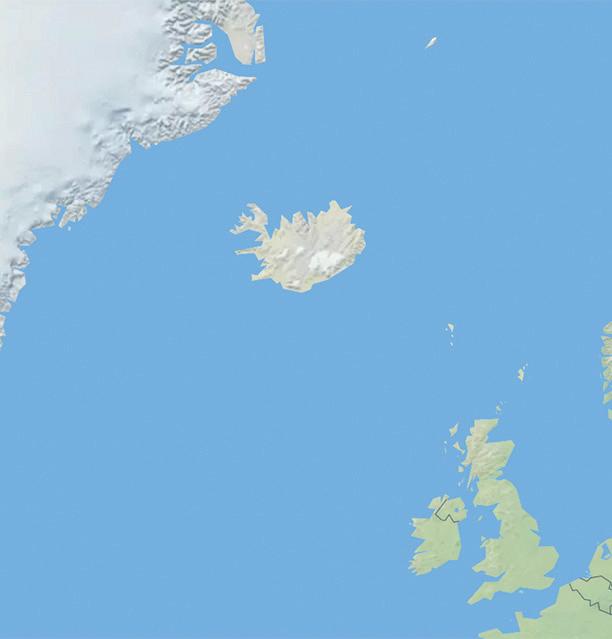

Iceland covers a surface of about 103,000 km2, which makes it about half the size of Great Britain and twice the size of the Netherlands. It lies just below the Arctic Circle and about 200 km off the east coast of Greenland.

Iceland is an extremely rugged country. Its coastline is indented by long, deep fjords, creating a coastline of about 5000 kilometres. In many places, the land rises steeply from the ocean’s depth.

Iceland’s interior is dominated by a large wild highland, that is completely uninhabited – a land of polar deserts, barren mountains and icecaps. The three largest icecaps, the Vatnajökull, Langjökull en Hofsjökull are all situated in the central highlands and cover together about 10% of the land’s surface.

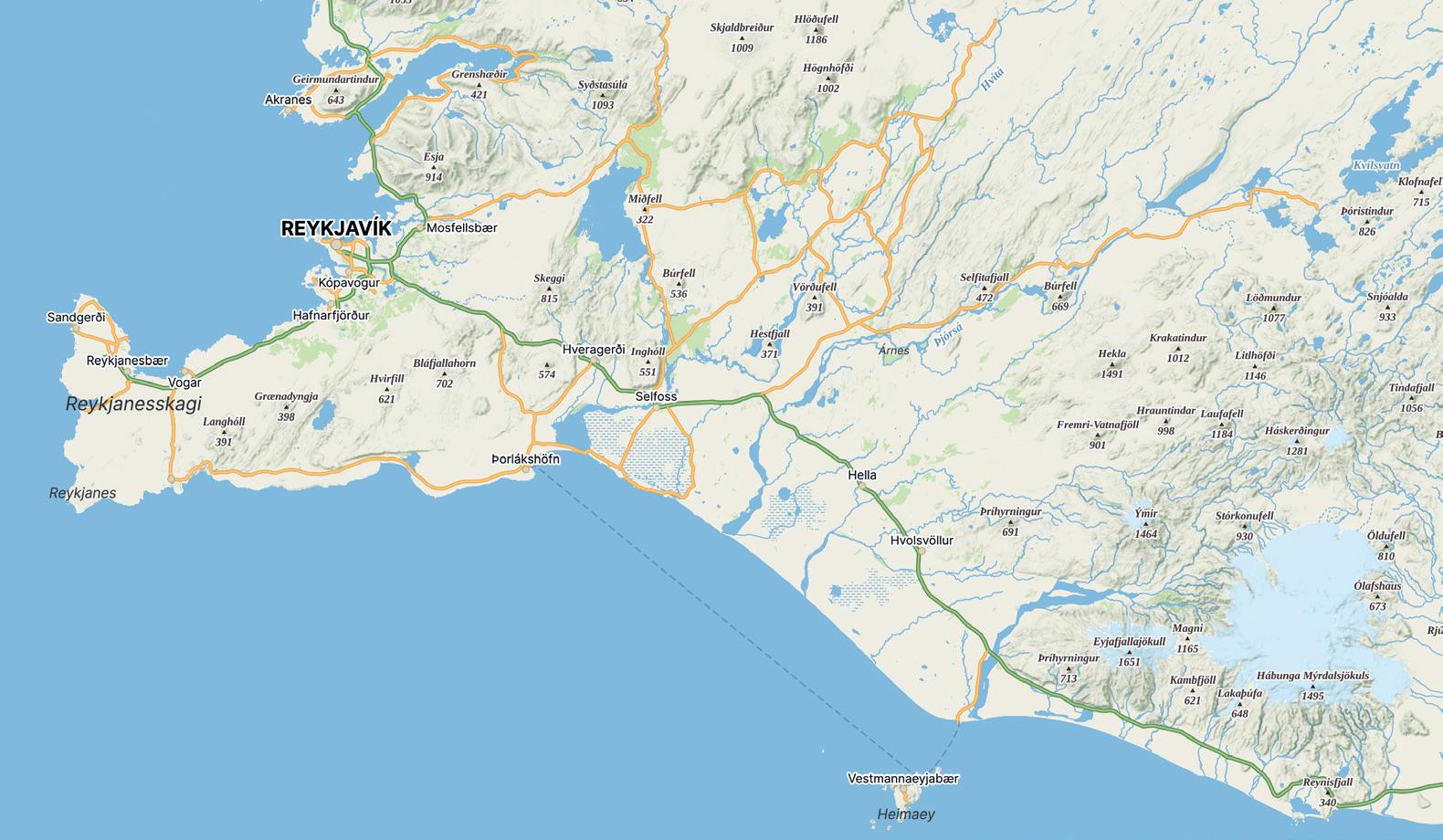

Most of Iceland’s 390,000 inhabitants (2025 census) live in the coastal region. Two out of every three inhabitants live in the greater Reykjavik area (the capital plus satellite towns). The plains of Selfoss and the towns of Akureyri in the north and Egilsstaðir in the east also house a fair number of people. These areas correspond with the country’s most fertile and flat lowlands and are far apart. Ring Road one, the nation’s logistic traffic vein, circles the country and connects these areas. It is the road you’ll inevitably take as you visit Iceland.

Most international visitors to Iceland arrive at Keflavik international

Airport in the southwest, not far from Reykjavík. The south-western corner of the country is also where you’ll encounter some of the most famous sites and geothermal phenomena, such as the Skogafoss and Gulfoss waterfalls, the blue lagoon, the Strokkur geyser and the Þingvellir plain, where Iceland’s parliament and court were once housed (see page 64 and route 1). The routes and sites in this area are described from page 122 onwards.

North of Reykjavik lies the Snæfellsnes peninsula, where one of the three National Parks of the country are situated (next to Þingvellir and Vatnajökull). Snæfellsnes is sometimes referred to as Little Iceland, as it combines every landscape type of the country within a small area. It is relatively easy to visit and offers superb scenery and birdlife. The routes and sites in this area are described from page 149 onwards.

Beyond Snæfellsnes, on the far side of the island-dotted Breiðafjörður (broad fjord), lie the West Fjords. This is Iceland’s wild, empty and little visited north-west region. The many deep fjords and rocky peninsulas make travel here time consuming, but the stunning nature, rich wildlife (including many sea bird colonies) and authentic villages make a visit very worthwhile. The routes and sites in this area are described from page 161 onwards.

The northern fjords, in particular the wide Eyjafjörður bay near Akureyri, harbour Iceland’s second largest concentration of inhabitants. Akureyri is a small town and a gateway to the spectacular inland sites of the north, which include impressive volcanic landscapes, dramatic waterfalls, a rich flora, remnant patches of subarctic woodland and, above all, the glorious Mývatn lake, which will prove a highlight of any trip to Iceland. The routes and sites in this area are described from page 176 onwards.

The coastline of east Iceland is again dominated by fjords. These East Fjords are where you’ll first set foot if you arrive by ferry. The international ferry arrives at the village of Seyðisfjörður, which lies close to the valley of Egilsstaðir, the main concentration of human habitation in this part of the country. The routes and sites in this area are described from page 207 onwards.

Southeastern Iceland has a dramatic landscape, dominated by the Vatnajökull. This is Iceland’s largest icecap which also harbours its highest peak, the 2.119 m high Hvannadalshnúkur. The southeast is a land of extremes, even by Icelandic standards. There are glaciers and icecaps, but also vast, barren plains of volcanic ash (sandurs – see page 38). In Skaftafell, a wonderful hiking area, there are important remnants of the Icelandic natural birch woodland. The southeast is also the location of the iceberg lagoons – a superb attraction for photographers and naturalists alike. The routes and sites in this area are described from page 216 onwards.

Too hot to handle. The geology of Iceland is spectacular, but not without its dangers.

Iceland is famous for its amazing geology. The chaotic shapes of the lava fields and the rhythmic patterns of the basalts, the stinking boiling mud and the immense expanses of the icecaps – it all begs the obvious geological question: how on earth did these landscapes take shape? Iceland is the result of the – often violent – clash of three gigantic forces. First, there is the hot magma that boils underneath the surface, gradually building up the pressure that eventually leads to a violent eruption. Secondly, there is the perpetual movement of the seas and rivers that ceaselessly eat away at the bedrock and deposit it again elsewhere as fine-grained sand. Finally there are the immense weight and erosive powers of the ice. When these three very different powers meet, there are – often literally –geological fireworks which have created the bizarre landscape of Iceland today.

Iceland’s soils are almost entirely volcanic. This in itself is not unique –there are many volcanic places in the world. But on Iceland, volcanism is taken to another level.

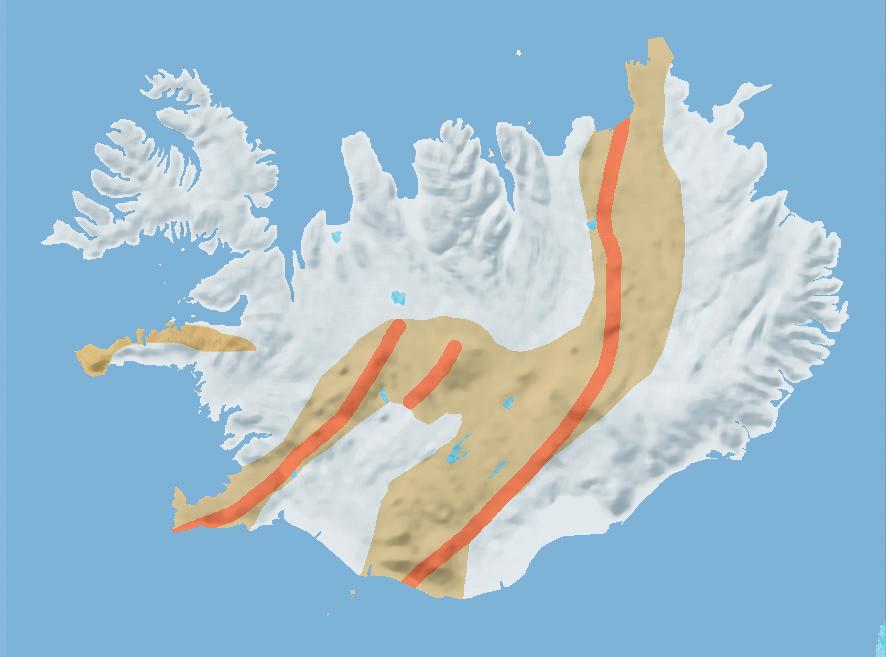

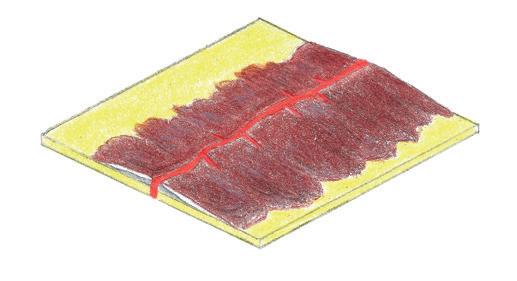

Fault lines and active volcanic zones of Iceland. The fault lines are most easily visible at Þingvellir (route 1) and Mývatn (routes 14-16).

Iceland lies right on top of the Mid-Atlantic Ridge, a rift valley that is formed as the sea floor spreads. Magma wells up from the cracks as the crustal plates pull apart. Like a sore wound that is torn open over and over again, the earth crust cracks open and magma flows out. In contact with the cold water, it creates two ridges with a depression in the centre where the bedrock is relatively warm and compact. The MidAtlantic Ridge runs along thousands of kilometres of the Atlantic seafloor, lined by countless volcanoes and eruption zones. Not all volcanism takes place on the contact zones of tectonic plates. Sometimes, volcanoes erupt because they lie above a mantle plume – a thin spot in the earth mantle, creating a plume

of hot magma from the mantle into the crust. Because the crust is much thinner here, eruptions take place more easily.

There are few places on earth where a mantle plume just happens to be situated right underneath a rift valley. Iceland is one of those few places. Here, not only is the crust stretched until it cracks due to tectonic movement, there is also a continuous pressure of magma close to the surface, seeking a way to escape. In fact, this explains why Iceland exists. Submarine eruptions were so frequent and accumulated so much lava that it eventually rose out of the sea to form a brand new land: Iceland. Icelandic volcanism is not only very active, it also produces some of the most diverse volcanic landscapes and the widest array of volcanic phenomena in the world. This is because Iceland has not only suffered eruptions on land and underneath the ocean, but also beneath glaciers – three entirely different conditions, each creating very different landscapes (see page 20). The creation of new land through volcanism is just half the geological story. Volcanic rocks are brittle and easily erode. There are four main eroding processes. First, the choppy seas ceaselessly eat away the coasts. Second, there are the eroding winds that pick up sands and scourge the land. Third are the wild rivers that dig themselves into the land. Finally, during the ice ages, the glaciers shovelled the earth down into the valleys and the ocean. While bedrock is taken away at one place, it is deposited elsewhere. In the coastal lowlands, thick layers of sediment have created a landscape with lagoons, deltas and sandurs – the final ingredient of Iceland’s geology.

All these processes have sculpted Iceland into a uniquely wild land with an extreme diversity of landscapes. Nevertheless Iceland’s geological makeup is quite straightforward. The country is spreading out from

The Láki craters form a line along the fissure and are a good example of a fissure eruption (site 55 on page 228).

the central rift valley (actually there are two which join in the centre of the country – see map). The bedrock is youngest in the centre of the rift valley. Along these lines, the majority of the active volcanoes and geothermal phenomena are found.

As you proceed towards the eastern and western extremes of the country, the land gets older. Here you find mostly landscapes sculpted by erosion, such as steep cliffs and deep fjords.

Lava-covered land and volcanoes constitute the larger part of the country. About 10% of the surface consists of lava erupted within the last 10,000 years. This young lava has hardly been touched by the smoothening forces of erosion and is one of the reasons Iceland has such a wild and rugged appearance.

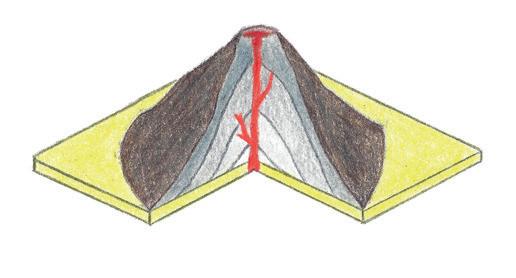

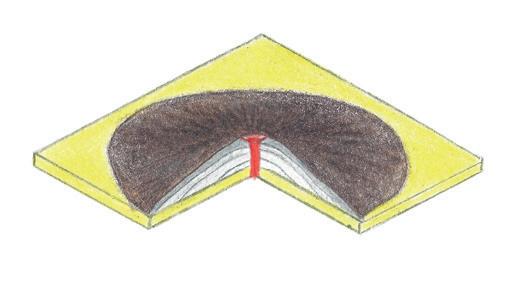

There are various types of volcanoes and they have deposited very different types of material.

The frequency of eruptions determines the height of volcanoes — regular eruptions in the same location produce high mountains of alternating layers of ash and lava with a deep, central vent. These are the classic strato-volcanoes from children’s books. On Iceland, Hekla is a good example of a strato-volcano.

Conversely, single eruptions, which are not uncommon in Iceland, leave low craters, often aligned along fissure lines. The famous example are the Láki craters, which formed in 1783, when a fissure of 25 km long opened and eruptions occurred all along its length. The craters that were left behind are one of the highlights of Iceland (see site 55 on page 228).

Strato-volcano Classic, high, pyramidal volcano with a large crater, which is the result of frequent and often violent eruptions on land. Examples on route 3, 7 and 15.

Shield volcano Low, plate-like volcano resulting from a prolonged eruption with low-viscous lava. Example on route 1 and along the 550 north of Þingvellir.

Fissure eruption Row of eruptions, some slow, some violent along a crack in the earth resulting from the spreading of tectonic plates. Example: route 15 and Láki craters; site 55 on page 228.

Pseudo-crater Small crater resulting from steam explosions as hot lava covers marshland. Example: Mývatn (route 14).

The volume of material produced in Icelandic eruptions varies enormously from event to event. The Láki eruptions were, in terms of volume of lava, the largest eruption of recent times. Approximately 12 square km of lava, an incredible volume, was produced (see also page 68). To put this in perspective, during the explosive eruption of Eyjafjallajökull that caused so much trouble to air traffic in 2010, only a fifth of a cubic kilometre of material was ejected – less than 2% of the Láki eruptions!

Most new land, though, is not created by explosive eruptions. Rising magma generally doesn’t break through the crust to reach the surface but spreads laterally to form intrusions called dykes into the surrounding bedrock. Sometimes, the lava does reach the surface unhindered and leaks out over the surrounding land. Especially when the lava is runny and there is only a single point of eruption, the ‘eruption’ can continue for a long time, creating a beautiful, low, wide-based hill, known as a shield volcano.

So not all eruptions produce the classic volcanoes, but to complicate things further, not every mountain with a distinct crater, is actually a volcano. When hot lava flows across a marshland or a shallow lake, it boils the water, but at the same time it closes it off, trapping the steam.

Even though Iceland overwhelms in its emptiness, it is actually an island with a good deal of different habitats. They form a fine blend, the one subtly merging into the other as the terrain changes.

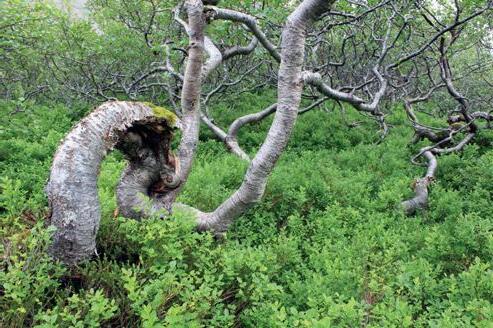

Paradoxically, for a country that is nearly devoid of trees, the simplest way to understand the Icelandic landscape is to view it as one big attempt to establish a forest. At Iceland’s latitude, climatic conditions favour the establishment of woodland as a climax vegetation beneath an altitude of about 400-600 metres above sea level. For instance, if you visit a part of Sweden or Finland at the same latitude, you are surrounded by endless forests.

The Atlantic conditions in Iceland create very cool summers, which shorten the growing season considerably, so that it is just long enough to allow a scanty growth of trees. Trees grow slowly and woodlands take ages to establish. Just a slight deterioration in the environmental conditions will tip the balance towards treeless habitats.

Unfortunately for the trees, Iceland doesn’t deal in subtleties. Spells of massive snow fall, flash floods, streams of lava, boiling water that flows

out from the ground, massive ash fall – any of them will wipe out any hope for a woodland to establish. The habitats that form instead, range from relatively lush heathlands to grasslands and barren deserts and lava fields, depending on the environmental factors that made tree growth impossible. All have their own beauty, sometimes wild and eerie, and sometimes lush and green, with an attractive flora and fauna. Some of these habitats are very typical for Iceland. The lava fields, the tephra deserts, the outwash plains and the geothermic zones where the land is permanently hot and unstable – they are all typically Icelandic habitats. Others, like arctic deserts, tundra heathlands, bogs, lakes, glacial rivers, mountain slopes and snowbeds, are found elsewhere in the arctic or in alpine areas as well, but the isolation and unique genesis give these habitats a unique Icelandic twist.

Given this temperamental nature of Iceland, only about 20% of the territory has the climatic conditions that favour the formation of woodlands. Again unfortunately for the trees, these are also the best lands for agriculture. Many of the pastures and meadows are in former wooded areas – these are now man-influenced habitats with a distinct and often rich flora and fauna.

The most beautiful cliffs and headlands, most of them with seabirds, are found on routes 4, 5, 7, 9, 18, 19 and sites 2 and 3 on page 141, site 24 on page 172 and 38 on page 206. Tidal mudflats and low rocky islets form an important feature on routes 2, 6, 8 and 20. Sandurs and sandy estuaries can be admired on routes 2, 5, route 9 (the nearby ‘red sands’),19 and 23, as well as sites 42 on page 213 and 49, 52 and 54 on page 226-228. Beautiful fjord landscapes are part of routes 7, 11, 12, as well as in the East Fjords.

Birds everywhere you look. Tens of thousands of them. You need to hold a stick over your head to avoid being attacked by the terns or skuas. There are massive bird cliffs, where millions upon millions of birds breed. With 3 million pairs, Iceland collectively holds the world’s largest Puffin population. The largest bird cliff, Latrabjárg (route 9) alone has several million pairs of birds, including an estimated 2 million Common and Brünnich’s Guillemots.

The coast is where a lot of Iceland’s biological action takes place –fortunately for you as a visitor, it is also the easiest habitat to explore. This being said, it is hard to speak of the Icelandic coast as a unified landscape or habitat. The ‘coast’ consists of steep cliffs and deep fjords, but there are also beaches and outwash plains, sand and gravel bars, coastal lagoons, tidal mudflats, estuaries, headlands, skerries and stacks. What binds these habitats together, other than the fact that they are all situated on the coast, is the availability of enormous amounts of food and the relatively mild temperatures. This is the good life Iceland style – the ocean’s supply of fish is bounteous, while the coastal soil, enriched by nutrients brought down by rivers and an awe-inspiring amount of bird excrement, is a rich substrate for plants to grow.

The wide variety of coastal habitats is a manifestation of two processes: erosion and sedimentation. The eroded coasts are abrupt and have Guillemots and Razorbills. The cliffs of Iceland are home to some of the largest seabird colonies of Europe.

steep cliffs and slopes as their main characteristic (see page 28). Sedimentation coasts are the opposite. Fine-grained materials like sand and tephra (ash), carried down by rivers, are deposited on shore by the currents. Such shores are level and frequently marshy.

Cliffs, headlands and skerries – the erosion coast

Iceland’s rocky coast consists of dramatic cliffs and stacks (rock pillars off the coast), all of which are formed by erosion.

The rough rock walls are full of clefts and ledges where sea birds breed – in particular Common and Brünnich’s Guillemots, Razorbills, Fulmars and Kittiwakes, with lesser numbers of Gannets and Shags (see also page 107 and further).

It is a cacophony of noise and life, present here solely because of the fish-stocked ocean. The cliffs are like chairs around a gigantic table, packed with delicacies within easy reach.

On Iceland’s west coast, the warm Gulf Stream and cold Greenland Current collide. Where these waters mix, there is a heightened concentration of nutrients and fish, from which sea birds profit.

All this food, processed through the bird’s gut, finds its way to the cliffs and on the rolling grasslands above the cliffs. The guanotrophic (dungfed) environment is readily recognisable by the occurrence of various plants, in particular Common Scurvygrass and, on rocks, the bright orange Xanthoria -lichens.

The abundance of birdlife attracts predators. Gulls, skuas and, in some places, Arctic Foxes, are drawn by the easy prey of chicks and eggs. They concentrate around the more easily accessible nest sites on the edge of the cliffs, hence the largest concentrations of seabirds tend to be on the steepest, hardest-to-reach cliff faces.

At Dyrhólaey (route 5), broad, black lava beaches and massive sea cliffs occur next to one another.

The cold Greenland current and warm Gulf stream collide near Iceland. This is why the Icelandic seas are full of life.

The endless Skeiðarársandur (site 49 on page 226) is Iceland’s largest outwash plain. It is the result of various flash floods from the Vatnajökull glacier, as well as marine and riverine sedimentation.

Where broad rivers run down from the highlands to the shores, sediments collect and are deposited at the coast, forming coastal lowlands. On Iceland, precipitation is high, and runoff is largely concentrated around the few months when temperatures are above zero. The force with which runoff takes place is therefore enormous (hence those impressive waterfalls). Add to this the brittle nature of the basaltic bedrock and large amounts of tephra in the mountains, and it is clear that rivers are loaded with suspended material. All of this sinks down as soon as the water flow slows as it reaches the ocean. The ocean, in turn, washes up sand and pebbles on levees on the coast. This is why a young country like Iceland has such large coastal flats.

The ever-changing course of rivers leaves behind a myriad of lagoons, marshy flats and coastal grasslands, some of which have been converted to meadows. Again it is the birdlife that immediately draws the attention. Big colonies of Arctic Terns, Eider Ducks, gulls and skuas breed along the coast.

In some areas on the west and the south-east coasts, there are extensive mudflats, which fall dry during low tide. At the coast of Mýrar (route 6), around the island of Flatey (route 8) and near Djúpivogur (route 20), the sea between rocky islets silted up, connecting them during low tide

and separating them again when the sea water rises. The maze of islets, rocky coastal pools and mudflats, all rich in nutrients, are of supreme importance to birds. Both breeding and migrating birds find food here. Many species take advantage of the tidal marshes. The rarest and most sought-after bird of Iceland, the Grey Phalarope, is even exclusive to such sites. It prefers quiet, rocky tidal pools.

The sand and pebble bars and dry coastal grasslands are important wildflower habitats. Sand bars at the shore are the haunts of Oysterplant, Sea Sandwort and Sea Rocket, while the grasslands sport a large number of flowers including some attractive gentians, like Golden Dwarf and Windmill Fringed Gentian.

A very special kind of coast is found in the south, especially the Vatnajökull. Here, flash floods have deposited vast outwash plains of volcanic ash: sandurs . In a few estuaries in the north (e.g. north of Ásbyrgi and north of Egilsstaðir) there are also outwash plains. Sandurs are largely devoid of vegetation and laced with small rivers. The tephra is soft and rivers keep digging out different courses in it. As such, it is an impossible habitat to penetrate. The ring-road passes a stretch near Skaftafell. It was the last part of the road to be paved – as late as the 1970’s! It is also the part that is washed away most frequently.

The quietude and level terrain makes the sandur an important breeding habitat for birds. The bird par excellence is the Great Skua – Iceland’s only colonies are found on these plains, while vice versa, the distribution map of this bird corresponds quite well with the position of the sandurs

Low tide in the Kaldalón fjord (route 12).

During low tide, the fjords are excellent for waders, while ducks, swans and divers can be found at high tide.

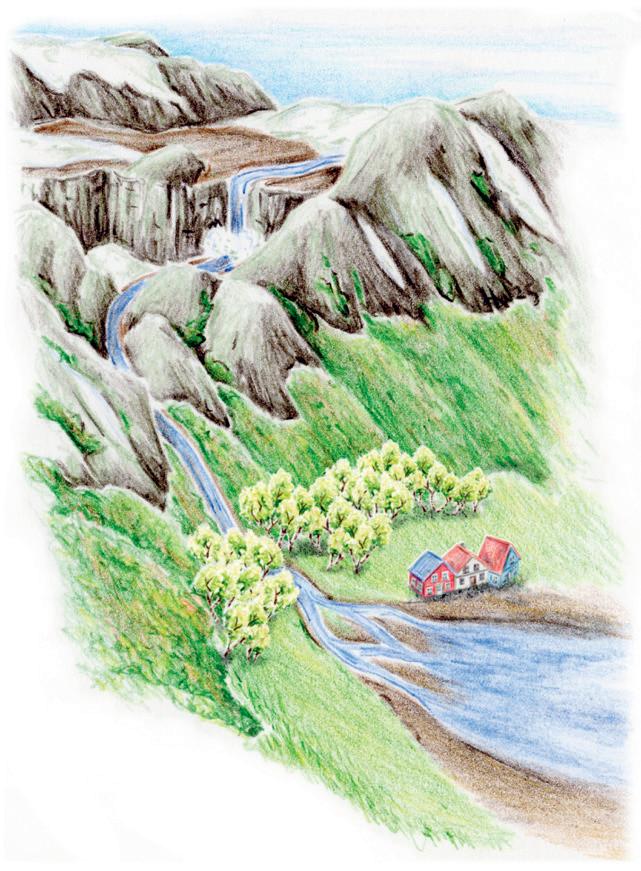

Fjords are created by erosion, as glaciers scoured out U-shaped valleys as they dug their way to the ocean. Later, rivers found these ‘prefabricated’ valleys a natural route down from the mountains to the sea, depositing a small estuary at the base of each fjord, not infrequently with one or more coastal lagoons.

Fjords are miniature versions of Iceland.

All the habitats, ranging from coastal mudflats to highlands, occur in swift succession.

1 - Tidal mudflat

2 - Coastal grasslands

3 - Birch woodlands

4 - Heathland

5 - Sparsely vegetated land

6 - Highland

As such, a fjord is a mixture of all coastal habitat types, combining cliffs, estuaries, coastal lagoons and tidal mudflats. The mild coastal climate and shelter against wind, allows for a more lush plant growth in fjords than elsewhere. Hence, some fjord valleys support remnants of Kjarr birch woodlands (in particular on routes 10 and 11). In quick succession, a fjord valley has coastal gravel and grasslands, birch woodland or meadows, heathland and sparsely vegetated land with a highland flora. So it is not surprising that some of the richest bird and wildflower sites are found in fjords. The smaller and remote fjords, which are not of interest to agriculture, are especially splendid. You’ll find them both in the West and the East Fjords.

The vegetation of springs, sources and brooks can be explored on routes 3, 7, 12 and 21. Rivers form a large component of routes 3, 12, 14, 17, 18 and 19. Bird-rich lowland lakes are a feature of routes 1, 2, 6, 14, 19 and 20. Admire Iceland’s estuaries on routes 2, 12 and 18, and site 37 on page 205, site 42 on page 213 and site 46 on page 215.

From the glaciers of the interior highlands to the river mouth at the shore, freshwater creates many different habitats. These ‘wetlands’, as they are collectively called, form their own proper hydrological system. Consider a drop of water or a snowflake that gets locked in a glacier. Once released, its journey typically passes through a meltwater stream, an upland lake and a mountain river (in Iceland usually involving a dramatic waterfall or two), before feeding the estuary marshes at the coast. Sometimes the journey is long. For example, water from the snowflake that falls on the northern slope of the Vatnajökull glacier, enters at some point the large Jökulsá á Fjöllum river, travels over the highlands all the way to the Dettifoss waterfall and through the Öxafjörður sandur, to end its ride in the Öxafjörður bay. Sometimes the route is much shorter. The snowflake that falls on the south slope of that same Vatnajökull may never be present in Iceland in liquid form: part of a clump of ice, it enters the iceberg lake of Jökulsárlón, squeezes itself through the 50 metres long outflow channel to melt on the shores of southern Iceland.

From the air on a clear summer’s day, the tundras of the far north of the globe look like a mirror. The water in the marshes reflects the light and reveals that the tundras are in fact more water than land. This is not because of the high precipitation levels in the far north. In fact, most polar climates are rather dry. Rather, it is because the sub-zero temperatures lock all precipitation between late autumn and late spring in ice. In summer it suddenly thaws, but since the underground is still frozen (in permafrost conditions it stays frozen year-round), it remains on the surface as a marsh.

On Iceland, there are considerably fewer marshes and lakes than on tundras elsewhere, although there are still quite a few. This is because there are few spots with permafrost and in many places the soil is very permeable. Nevertheless, the high precipitation and sudden discharge as the ice melts, is enough to feed the hundreds of lakes in the country. As the ice lock springs open around May, water runs off the hillsides into the rivers. It brings with it large amounts of small particles and nutrients. Ecologically, the Icelandic rivers are like ribbons of food and

Every visitor to Iceland is amazed by the enormous numbers of birds found there. There are huge seabird colonies with millions of Puffins, Guillemots and Razorbills. The grasslands are full of waders and in the lakes, large numbers of ducks can be found. Divers, swans and phalaropes are common. In short, the sheer quantity of birds makes Iceland a true wildlife spectacle.

It also masks the fact that the country actually has a very low biodiversity. In fact, it is the only European country without any butterflies or dragonflies, nor are there any reptiles or amphibians. There is only one native land mammal, the Arctic Fox. Even birds, though present in large numbers, all belong to just a few species. With just under 500 species of higher plants, Iceland has but a sixth of the native British flora and less than a third of the Dutch flora –two countries that themselves are hardly known for their abundance of species.

The reason for this paucity is easy to grasp. Iceland’s northern location creates conditions that support relatively few species while its isolated position makes the country hard to reach – both for migrants and potential colonisers. The nearest land is Greenland – not exactly a place where life proliferates either.

On top of that, the land is very young – not just geologically, but also biologically: only 13,000 years ago, the country was largely or entirely covered in ice. Although some biologists believe some enclaves of vegetation remained during the last ice age (see page 93), life pretty much vanished. Hence, (almost) every species that is native to Iceland, colonised this remote island in the last couple of thousands of years.

In several areas in Iceland, you can see the graceful Shorteared Owl, hunting over the meadows and lupin fields.

The country is under the influence of both the boreal (northern coniferous forest belt) and the arctic biological spheres and its flora and fauna has elements of both. In the sheltered and lowland areas, the boreal species are dominant (e.g. Redwings and Redpolls among the birds, and Northern Bedstraw and Wood Crane’s-bill among the plants). Some species have a much wider distribution, reaching deep into Europe, such as Lady’s Bedstraw and Herb-paris amongst the plants, and Redshank and Meadow Pipit amongst the birds.

The Arctic species are, of course, found in the more barren places. An interesting phenomenon of the northern regions is that, as the earth is a globe, the distinction between east and west increasingly becomes meaningless the further north you travel. Indeed, at the North Pole the only direction you can go is south! Many arctic species have colonised the northern world in a band around the pole. They are circumpolar species. Typical examples are Grey Phalarope, Arctic Fox and Arctic Poppy.

The close proximity of Greenland, and beyond it the American Arctic, subjects Iceland to distinctly American influences in its flora and fauna – species that are, of course, highly attractive to European visitors. The “Americans” are represented with some flashy species, such as Great Northern Diver (known as Common Loon in America), Harlequin Duck and Barrow’s Goldeneye. These species do not breed elsewhere in Europe. Among the plants, Northern Green Orchid, Arctic Riverbeauty and Marsh Felwort are good examples. Iceland’s catalogue of life does not only list boreal and arctic species. The third factor that plays a strong role is the ocean. Many species found in Iceland are strongly tied to the northern Atlantic. In fact, the Atlantic is an important engine to life on Iceland. The vast numbers of birds, in particular sea birds, are here because of the Icelandic seas. The warm Gulf Stream and cold Greenland current meet here, creating very rich fish grounds, of which sea mammals (e.g. Killer Whale) and sea birds (Gannet, various species of auks) take advantage. These are some of the typical representatives of the Atlantic fauna.

Plant species with a distinct Atlantic distribution are, in contrast, rather rare. The Atlantic ecozone is characterised by a flora that withstands winter cold rather badly. Although Iceland’s winters are generally mild compared to areas of similar latitude on the mainland, they are still quite cold. In combination with the remoteness of the island, this is probably the reason why typical Atlantic plants are rare. One representative of the Atlantic flora, the Small Adder’s-tongue, found a way to stay warm. It is restricted to geothermal areas.

American region

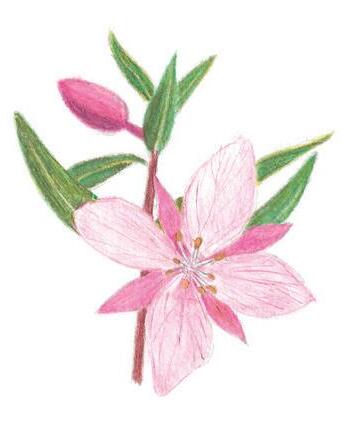

Arctic Riverbeauty

Epilobium latifolium

River banks

Arctic region

Arctic Fox

Vulpes lagopus

Coasts and heathlands

Atlantic region

Puffin

Fratercula arctica

Cliff coasts

Temperate region

Herb-paris

Paris quadrifolia

Lava fissures

Boreal region

Redwing

Turdus iliacus

Woodlands and heathlands

In early summer, the Mountain Avens (top) and Moss Campion (bottom), flower in the arctic heathlands and sparsely vegetated mountain slopes.

Some excellent excursions to find wildflowers of heathlands and dry grasslands, including many orchids and gentians, are routes 3, 5, 7, 13, 14, 15, 17, 20 and 21. We found a rich coastal flora on routes 2, 7 and 20. Attractive woodland species feature on routes 10, 15 and 21. The diverse highland flora is difficult to track down without four-wheel drive, but you won’t be disappointed on routes 12 and the highland point of route 19, and sites 41 and 45 on page 213-214. The flora of marshes and riverbeds feature on routes 2, 3, 12, and 21, but also check out sites 30 and 31 on page 201. For lava fissure flora, explore routes 1, 7 and 15 and site 23 on page 160. A marvellous flora of snowbeds and recently ice-free land can be found on route 12 and to lesser extent 22, 23 and site 14 on page 146. Wildflowers of hot springs are not easy to find. Try route 16 and site 28 on page 174.

Iceland has a flora of 489 species of vascular plants. This is a more limited number in comparison with similar-sized areas in Scotland or Scandinavia. Nevertheless, Iceland is a great place for botanists, because many of the species present are very attractive and occur in jaw-dropping quantities. Come in the right time, and you’ll be treated to masses of small wild orchids, pink ribbons of Arctic Riverbeauty lining the streams and a delightful sprinkle of white bells of the Moss Heath. The beauty of the flora of Iceland lies in its delicacy: the masses of fragile, small flowers contrast with the rugged beauty of the dramatic landscapes and sometimes sombre weather – a combination that never ceases to amaze.

If you are visiting Iceland for the first time, it will probably take you a couple of days to become adjusted to the quantitative overload of wildflowers. Once you’ve discovered what is the ‘common Icelandic flora’, you may want to track down some of the special species, like saxifrages (15 species in Iceland), gentians (7 species) and ferns (22 species). Once you are on that road, it won’t take long to recognise that many wildflowers have a curious

distribution – they are confined to very specific locations, whereas the habitat they occur in, is not. The rarity or absence of some species in certain areas is just as puzzling as the abundance of others. This opens the door to questions about how wildflowers established themselves in Iceland in the first place. That’s when the Icelandic flora gets truly interesting!

Your first encounter with the Icelandic flora is likely to be somewhere in the grasslands or heathlands in the coastal lowlands that fringe the country. Most of the country’s accessible sites and walks take you through this habitat. If you are here in July, then your first experience may be quite overwhelming. On a typical walk in the heathlands, you will find yourself wading through a well-scented bouquet of Crowberry, Bearberry, Heather, Bog Bilberry, Alpine Fleabane, Alpine Bistort, Moonwort, Slender Bedstraw, Lady’s Bedstraw, Alpine Cinquefoil, Alpine Lady’s-Mantle, Scottish Asphodel, Alpine Bartsia, Arctic Thyme, Mountain Avens and Grass-of-Parnassus. There are clumps of deep blue Alpine Gentians here and there, and, in open places, a scatter of Hairy Stonecrop and Butterwort, topped off by swathes of Northern Green Orchids, frequently accompanied by Northern Small White and Frog Orchids. What a wealth!

Higher up the mountain and in the north of Iceland, the heathlands change in character. The shrubs are lower and open patches in the vegetation emerge. This arctic version of heathlands reflects a more extreme climate and consists of different species. The tiny Moss Heath is common in wet patches, while Trailing Azalea and

Butterwort (top) and Alpine Catchfly (bottom) both prefer open patches in heathlands. Butterwort seeks out the moist sites, while Alpine Catchfly prefers the drier spots. In contrast to what the name suggests, the Butterwort is the insectivorous plant, not the Catchfly.

Northern Green Orchid

Platanthera hyperborea

A boreal-arctic orchid species of North America with its only European location in Iceland. Very common (all routes except 1 and 4). Habitat: open patches in heathland and grassland.

A pretty pink stonecrop that is rare in Scandinavia and the European mountains, but widespread on Iceland. It occurs on most routes. Habitat: open patches in heathland and grassland.

Arctic species of gentian with small, glossy-purple flowers. It is uncommon in the south (route 2, 4, site 53 on page 228), but very common in the north (routes 14, 18). Habitat: coastal grasslands

Marsh Saxifrage

Saxifraga hirculus

Yellow-flowered species of Saxifrage. It was once widespread all over Europe but became extinct in many countries. The cause of its demise is the destruction or deterioration of its fragile habitat of alkaline bogs. On Iceland, it is common in the highlands and rare in the lowlands (route 7 and site 13 on page 146 and 28 on page 174).

Arctic Riverbeauty

Epilobium latifolium

Smashing species of willowherb of the Greenlandic and Canadian Arctic. It is common in Iceland’s interior along rivers, gravel banks and roadsides. Route 2, 3, 12, 16, 17, 21, site 31 on page 201).

Marsh Felwort

Lomatogonium rotatum)

A pretty blue member of the gentian family. It occurs in the Canadian and Russian Arctic, but is absent from Europe, except Iceland. Rare except in the north-central and north-east of Iceland (site 30 on page 201). Habitat: open, moist patches close to rivers.

Another northern gentian species, occurring in northern Norway and Iceland. May form large populations in coastal grasslands. Routes 2, 7, 13, 14.

Arctic Poppy

Papaver radicatum

Conspicuous yellow poppy and a truly arctic species. Unique adaptation in which the petals function as a heat reflector, deflecting and funnelling the sun’s radiation to the ovary to aid the ripening process of the seeds. Frequent in the north-west, with other subspecies occurring in the north and east. Habitat: arctic desert, disturbed land, gravel banks, roadsides. Routes 7, 11, 12.

The following species groups are particularly well-represented in Iceland.

Mosses Over 600 species of mosses occur in Iceland, which is more than the number of wildflowers (489). Most of them you will pass unnoticed, but some species are incredibly beautiful. Very conspicuous are the fringe-mosses (Racomitrium) that grow on the young lava rocks. The greyish-green colour and soft, cushion-like appearance contrasts beautifully with the sharp and dark lava.

Ferns With 22 species of ferns, this group of spore-carrying plants is wellrepresented in the Icelandic flora. The majority of them are confined to clefts in rocks, cliffs and lava fissures. Some interesting species you may encounter on the routes in this book are Oblong and Alpine Woodsia, Holly Fern, Beech Fern and Oak Fern.

Sedges No less than 45 species of sedges occur on Iceland. They are successful partially because they don’t rely on insects for their pollination. Sedges are found in all habitats, including the most barren, wind-beaten plateaux. One special species is the Lyngebye’s Sedge, a conspicuous species that dominates marshlands. It is one of in total nine American plant species that, within Europe, are only established in Iceland (although, in case of the sedge, there is also a single locality on the Faroe islands).

Saxifrages Saxifrages are arctic-alpine plants par excellence. Fifteen species occur on Iceland, most of them are white-flowered and occur in the highlands or on cliffs. Several species (e.g. Brook Saxifrage, Starry Saxifrage, Yellow Saxifrage and Marsh Saxifrage) occur along mossy streams.

Gentians The gentian family is represented by 7 species. All of them are attractive and some are of interest because they don’t occur in southern countries. Alpine and Field Gentians are the most widespread, found in dry grassland, mostly at the coast. Golden Dwarf, Windmill Fringed and Autumn Gentians are all northern species and often common at the coast. Slender Gentian and Marsh Felwort occur along streams, mostly inland, and are therefore harder to find. Gentians don’t come into flower until late June, some even later.

Orchids It may come as a surprise, but we have never seen as many orchids as in Iceland, albeit just a few species. There are literally millions of them, growing in the dry grasslands and heaths all along the country. Of the seven species that occur on Iceland, the Northern Green Orchid (an American species) is most common and is seen on virtually any heathland, frequently in the company of Frog Orchid, Northern Small White Orchid and Coralroot (the latter two in lesser quantities). Twayblade is quite rare, and grows in rich woodlands. Lesser Twayblade is a species of mossy heathlands. It is fairly widespread, but very easily overlooked, hence the hardest orchid to find. Finally, the Heath Spotted-orchid with its flashy pink flowers is quite localised but abundant where it occurs.

The best chance of seeing Arctic Foxes is in the West Fjords: routes 9 to 12, but in particular on Hornstrandir (site 24 on page 172) and Heidadalur and the Arctic Fox Centre (sites 27 and 28 on page 173-174). The largest chance on seeing whales and dolphins are on routes 4, 7 and 13, but better still on a whalewatching tour (see page 247). Seal are frequently seen on route 20 and sites 24, 25, 26 and 28 on pages 172 - 175 and site 42 on page 213.

When the Viking settlers arrived on Iceland, they encountered only one land mammal: the Arctic Fox. This small, blunt-nosed relative of our familiar fox is the only naturally occurring mammal on Iceland, although occasionally, bats stray in from the south and Polar Bears drift down on sheets of ice from the north. For bats, however, the summer season is too short, and Polar Bears can’t survive without sea ice to hunt from. So it was only the Arctic Fox that was able to survive. It hunts for Ptarmigans, eggs and seabirds, and in season supplements this menu with berries and anything edible that washes ashore. The winter period is a harsh time for Arctic Foxes and sometimes over 50% of the animals die. The Arctic Fox copes with these losses by producing very large litters – with up to 20 pups the largest of any land predator in the world. Arctic Foxes have an all-white fur in winter which they replace with a brownish coat in the summer months. On Iceland, the usually rare “blue” form of Arctic Fox is quite common. About two thirds of the population has a slate grey (rather than blue) coat throughout the year, which blends in nicely with the dark lava.

An Arctic Fox steals an Eider egg. Its love for Eider eggs has given the Arctic Fox its bad reputation and is one of the reasons it is still persecuted in Iceland.

Reindeer are introduced to Iceland. There are several herds roaming both the highlands and lowlands of Eastern Iceland.

Foxes have had a hard time ever since the first settlers arrived. They have been heavily persecuted and, in some areas, they still are. The reason for the Icelanders’ hostility towards their only naturally occurring fellow mammal is the Arctic Fox’s love for the nests of Eider and because they are reputed to prey on lambs. Because foxes are still hunted, they are wary of humans. Although they occur throughout the country, they are low in numbers. Except in the region of the West Fjords, especially the Hornstrandir nature reserve (site 24 on page 172), where the foxes are not hunted, they are common and inquisitive.

Polar Bears regularly get stranded on ice sheets. During cold spells in winter, when drift ice reaches all the way to Iceland, Polar Bears may make it to the basalt shores. This happens quite often – although in irregular intervals. Once every two years on average, a Polar Bear is seen on Iceland. Most sightings are in spring, but there are summer records as well. For safety reasons, Polar Bears get shot, although some people now advocate tranquilizing the bears and returning them to Greenland.

Ever since their first arrival, people have introduced mammals. Reindeer were introduced in the 18th century in an attempt to start a new agricultural business. Currently, small herds roam the hills and highlands of east Iceland. A number of rodent species followed the Vikings and later migrants to Iceland. House Mouse and Brown Rat live primarily in towns and villages. The Wood Mouse came early, with the first settlers and has established in grasslands and farmland. The American Mink escaped from fur farms that formed a new industry in the 20th century. This member of the Marten family is a fierce and insatiable hunter of birds’ eggs and has a negative impact on the native bird populations.

The bulk of Iceland’s mammalian diversity isn’t found on land, but in the sea. There are 15 species of whales and dolphins regularly found in Iceland’s waters, and two types of seals. Whale watching is a true highlight of any visit to Iceland. Few things are as exciting as sitting on a small vessel in a fjord, Puffins and other auks dashing by, waiting for a whale or dolphin to break the surface. You never know where they will appear nor how far or near to the ship they will emerge.

One of the most commonly seen species is the Minke Whale. It is one of the baleen whales – the species that have large keratine plates in their mouth that sieve the sea water for krill, their main food. Baleen whales are the largest beasts on the planet and although the Minke Whale is the smallest within this group, it still measures a mighty 7 to 10 metres in length. Minke Whales regularly feed close to the shore.

Another baleen whale frequently seen is the Humpback Whale. It reaches a length of nearly 20 metres, and is known for its spectacular breaches out of the water. They don’t always do this, but on a whale-watching trip you may be treated to a great show.

Off the north-west coast, usually some 40 to 60 kms out at sea, the immense Sei, Fin and Blue Whales occur. The Blue Whale is the largest mammal of the world. Some exceed a length of 30 metres. They are usually solitary. There are 6 species of toothed whales that are frequent or common in the Icelandic waters. These animals prey mostly on fish or squid. The largest of them is the Sperm Whale, which is only seen during a very brief period in summer in the northwest. Only the bulls stray as far north as Iceland.

Common Seals often return to specific spots on shore to rest. This makes it easy to locate them. However, their grey skins are an effective camouflage, so they are easily overlooked.

Much more common are the spectacular Killer Whales or Orcas. They live in small groups and hunt for Herring. Killer whales reach a length of nearly 9 metres. In spring and early summer, they are frequently seen close to the coast of the Snæfellsnes Peninsula. In winter, they prefer deeper waters.

Among the dolphins, the White-beaked Dolphin and Harbour Porpoise are commonly seen. White-beaked Dolphins are mostly found in western Iceland, where they sometimes form large groups. The ferry to Flatey (route 8) is one good place to spot them. Harbour Porpoise, being the smallest (up to 2 metres) and shiest of the cetaceans (whales and dolphins), is quite hard to spot in the choppy Icelandic waters, even though it is common.

Less frequently seen cetaceans are Bottlenose Dolphin (mostly in summer off the south-east coast) and Long-finned Pilot Whale (in autumn along the south coast).

Iceland is home to a large population of seals. Both Common and Atlantic Grey Seal breed all around the coastline, but there are some specific places in the north (e.g. sites 24, 25, 26 and 28 on page 172 and further) and in the south-east (route 20) where you have a very good chance to see them. Common Seals (recognisable by their rounded, gentler faces) often haul out on sand bars while Grey Seals prefer to rest on rocky coasts. From time to time during the winter months, some arctic seal species visit Iceland. Ringed Seal, Harp Seal, Bearded Seal, Hooded Seal and Walrus have all been seen.

The richest sites for breeding wetland birds are on routes 1, 2, 6, 19, 20 and above all 14 (Mývatn). Very attractive too is the Öxafjörður (site 37 on page 205). During migration, routes 2, 6, 20 and sites 46 on page 215 and 53 and 54 on pages 228 are of particular interest. Great seabird colonies are on routes 4, 5, 7, 9, 18 and 19 and site 2 on page 141, and site 24 on page 172 and 38 on page 206. Ptarmigan and the breeding waders of the grasslands and heathlands can be found all over Iceland. Particularly attractive, also for photography, are routes 2, 6, 8, 13 and site 28 on page 174. Birds of prey are best seen on routes 11, 12, 14 and 17. The where-to -watch birdslist for each species is given on page 250.

Iceland is a birdwatcher’s paradise. Search on the internet for photos of Iceland and birds, or better yet a nature photographer’s website, and you’ll know why: beautiful birds, often seen at close range, occur by the thousands. Noisy bird cliffs are packed with Puffins, Razorbills and a variety of guillemots. Meadows are full of waders. Coastal lagoons are alive with Red-necked Phalaropes, Whooper Swans, divers and a variety of ducks. What Iceland lacks in mammals, reptiles and insects, it makes up for with birds, whose numbers impress even the most stringent non-birder.

The birdwatcher will not only be rewarded by the sheer number of birds, but also, perhaps more so, by the presence of some very sought-after species: Great Northern Diver, Harlequin Duck, Barrow’s Goldeneye, Slavonian Grebe, Gyr Falcon, Glaucous Gull, Grey Phalarope and Brünnich’s Guillemot (Red Phalarope and Thick-billed Murre respectively in American English). During a summer visit, you should be able to find all of them, except perhaps the Grey Phalarope, which is scarce and elusive.

In spite of this spectacular abundance, Iceland has relatively few species. Only about 79 species breed, while another 23 visit the island in winter or passage. Most breeding birds are relatively easy to find.

The reason for this lack of diversity is, as is the case of other groups, the combination of Iceland’s isolation in the north Atlantic, the relatively short period since it escaped from the freezing grip of land ice, and the hostile winter conditions. Hence only 27% of Iceland’s birds are residents – of all other species, either the entire or the larger part of the population migrate to Iceland to breed, to winter (a small number) or occur as wind-blown vagrants.

Iceland’s isolation is also the cause of another strange feature of its birdlife: the paucity of songbird species and the high proportion of rare birds (about 80%) on the national list – greater than any other European country! Since the late 1960s, enthusiasts have regularly found small

Meadow Pipits are everywhere on Iceland. They even breed in the Lupin Fields where otherwise not much life is found.

numbers of American vagrants in late autumn (including some ‘firsts’ for Europe like Rubycrowned Kinglet).

Despite an impressive Icelandic list of about 370 species recorded on the island, only 77 breed annually (although more do so irregularly). Only about a dozen are passerines (songbirds), namely Meadow Pipit, White Wagtail, Northern Wheatear, Redwing, Fieldfare (rare), Blackbird, Goldcrest, Icelandic Wren, Starling, House Sparrow (rare), Crossbill (rare), Snow Bunting and the Icelandics subspecies of Redpoll. Of these, Blackbird and House Sparrow only occur near habitation. Another dozen or so are frequent passage or winter visitors. Many familiar groups – accentors, warblers, swallows, tits or larks – are either absent or rare migrants.

This is all most likely due to the fact that Iceland lies far away from migration routes for small birds. Moreover, the country’s winter climate and lack of woodlands make it a very tough country for small birds to survive in winter. Iceland’s breeding birds are, not surprisingly, mainly sea birds and waterfowl, for which the seas are not so much of a barrier, and which provide plenty of food to survive and rear chicks.

The bird calendar for Iceland is quite straightforward: the migrating breeding birds arrive in April and May and depart again in the course of August and September, with some species lingering on until November. Within this period, Iceland is alive with birds. The near 24 hours of daylight allow birds to feed their young throughout the day, making the best out of the short summer. Outside this season, the interior of the country is almost deserted. Only Ravens, Ptarmigans, Gyr Falcons, Snow Buntings and in the woodlands, a handful of songbirds remain. The coast is actually quite interesting in winter. Several Arctic birds spend the season off the coast and profit from the good fishing grounds here. Notable winter visitors are Ivory Gull, Little Auk and King Eider. All of them are seen annually, but are quite rare. Much more common is the Iceland Gull, which, confusingly, doesn’t breed in Iceland at all, but comes from Greenland. Iceland Gulls are common birds throughout most of the year, except in summer, although there are always a few non-breeding birds around in groups of Glaucous Gulls.

Just before and just after the breeding season, so roughly in AprilMay and again from mid July to late August, some areas of Iceland are interesting for passage migrants. In spring, some birds stage on Iceland’s shores before heading out to their breeding sites in the interior of Iceland or further on, in Greenland. Iceland is an important stepping stone for some high arctic populations on the East Atlantic flyway to Greenland and Canada. These include Red Knot, Turnstone and Sanderling, and Brent, White-fronted and Barnacle Geese. The latter has started to breed in Iceland in recent years (see route 23), but the majority of the birds present in spring, continue further north. Good staging areas are the lagoons in the south (routes 2, 20 and sites 46 on page 215 and 53 and 54 on page 228) and Mýrar (route 6). This is where you will find large concentrations of waders, Whooper Swans and geese.

In mid-July, the birds return to the coast, their numbers now boosted by the season’s young birds. They will stay for a while to “fatten up” before starting their journey southbound over the choppy Atlantic waters.

Marshes, lakes and rivers are prime bird habitats. This is where large numbers of ducks, divers, grebes and waders can be found. No less than 16 species of ducks breed annually in Iceland and all, except Eider and Shelduck, breed in wetlands. The most common ducks in Iceland are Mallard, Wigeon, Teal, Scaup and Tufted Duck. These species occur throughout the country in many types of lakes. Less common are Gadwall, Shoveler and Pintail. These ducks of temperate Europe are restricted in Iceland to nutrient rich lakes with a rich aquatic vegetation. You’ll find them only in some specific marshlands, such as those around Akureyri, Djúpivogur (route 20) and Mývatn (route 14).

Bird photography

Note that although birds are approachable, it doesn’t mean they can’t be disturbed. Make sure you keep your distance and back off when birds show signs of disturbance. A pretty picture for you may result in loss of eggs or young for the birds.

few male King Eiders are present on Iceland’s coasts throughout the year, but their numbers increase in winter. They usually mix with the Common Eiders.

Overview of southwest Iceland. The numbers refer to the routes on the following pages and the letters to the sites described on page 141-148.

Since most visitors arrive in Iceland by air at Keflavík International Airport, it is the southwestern section of the country people will see first. More specifically, the first experience will be with the large, sombre and somewhat monotonous lava fields of the Reykjanes Peninsula where the airport is located. It won’t take long though, before one discovers that the southwest is a varied and rich part of the country. Southwest Iceland is both the most densely populated region and the one with the highest concentration of iconic sites like Þingvellir (route 1), the Gulfoss waterfall and the geyser of Geysir (site 8 and 9 on page 143144), which together form ‘the Golden Circle’ of most popular tourist sites. Another famous site is the Blue Lagoon (site 4 on page 142) and, of course, Reykjavík is in itself an attraction – a lively and modern town which, if one includes its satellite towns, is home to 2 out of 3 Icelanders.

The relatively high number of inhabitants and visitors by no means make southwest Iceland less wild or attractive from a naturalist's pointof-view. This region has a rich birdlife and flora and is, geologically and scenically, simply breath-taking.

The mid-Atlantic ridge, surrounded by volcanoes, cinder cones and extensive lava fields, cuts straight through southwest Iceland and can be admired at Þingvellir (route 1). Associated with this ridge there are

extensive geothermal areas, which can be visited at Rekjanesviti (site 3), Krúsavík (site 5), Hverargerði (site 10) and of course at Geysir (site 8) on page 141-145.

Reykjavík lies towards the west of this ridge and is one of the three main spots from which you can go on whale-watching excursions (see 7 on page 143). The plain of Selfoss, the largest agricultural area, lies east of the ridge. Here are important meadows and marshes (routes 2 and 3), where many waders, Short-eared Owls and Arctic Skuas breed. On the coast, there are spectacular cliffs with important seabird colonies, which house the largest numbers of Gannets and Puffins and the only colonies of Manx Shearwater in Iceland (route 4 and 5, sites 2 and 3 on page 141).

East of the Selfoss plain, the icecaps of Eyjafjallajökull and Mýrdalsjökull emerge. Here you have an excellent opportunity to get a taste of the highlands. Route 3 brings you into the highlands (even with a 'normal' car), while the walk towards the Sólheimajökull (site 14 on page 146) offers a unique opportunity to explore a glacier up close. The wild and scenic inland areas of Þorsmörk and Landmannalaugar (sites 18 and 19) can only be visited if you have a four-wheel drive, or by taking one of the regular bus services. These two very scenic areas are the most popular hiking destinations in Iceland.

Finally, southwest Iceland has some of the most famous large waterfalls in Iceland: the Gulfoss (site 9), the Seljalandfoss (site 12) and the Skogafoss (site 13 on page 146).

All in all, it is safe to say that you could spend an enjoyable trip just in the southwest. The sole reason to go to other parts of the country is not that your options in the southwest are limited, but that the other regions are similarly spectacular and yet offer a different kind of Iceland.

Highlights

• Spectacular geothermal (volcanic) sites, including boiling mud pots, steam vents and the famous Geysir.

• Þingvellir, Iceland’s most important historic site, with a fascinating ecology and geology, as it is the cleft between the American and European tectonic plates.

• Landmannalaugar and Þórsmörk are the most popular hiking areas of the country.

• Rich birdlife of meadows, marshes and seabird colonies.

• Relatively easy access to glaciated highland areas.

• Gulfoss, Seljalandfoss and Skogafoss, three of the country’s most impressive waterfalls.

• Whale watching excursions.

• All this with easy access from Iceland’s capital, with its rich cultural life.

Various pairs of Great Northern Divers breed on the lakeshore of Þingvallavatn.

Beautiful walk in a historically and geologically interesting place. The climax vegetation of Iceland.

Habitats: cliffs, lake, birch woodland, heathland

Geology: rift valley, shield volcano, ropey lava

Selected species: Beech Fern, Alpine Woodsia, Northern Bedstraw, Frog

Orchid, Red-throated Diver, Great Northern Diver, Redpoll, Icelandic Wren, Red-breasted Merganser, Red-necked Phalarope

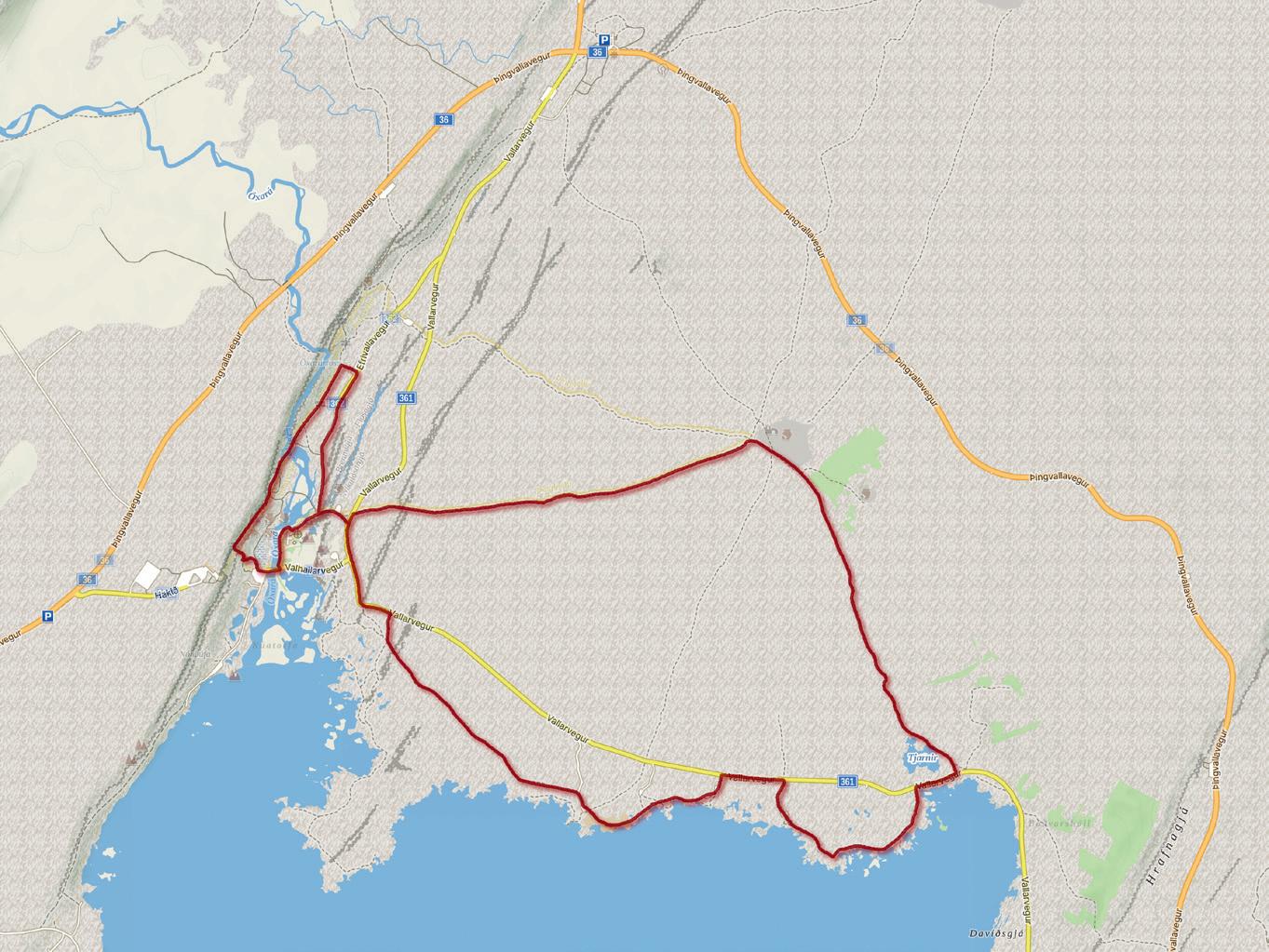

Þingvellir is part of the 'Golden Circle' – the ring of classic sites every visitor has to see (the others being Geysir and Gulfoss). Þingvellir is both a main historical and geological site. It is where the Viking settlers first met to form a parliament and court almost 1100 years ago. Here laws were formed and courts were held (see history section). It was, and in many ways still is, the heart of Iceland. While Þingvellir is the point where the Icelanders bind together, it is geologically quite the opposite, namely the site where the land pulls apart. The Þingvellir (vellir means valley) lies on the edge of the American and Eurasian tectonic plates. It is here that they drift apart and the many cracks and clefts are evidence of this. The valley itself is clad in a natural shrubby birch wood of the type that has become very rare in Iceland.

This route consists of a short walk through the historic site of Þingvellir and a longer one through the woodlands of Þingvellir National Park. Both leave from the same car park but while the first is crowded with tourists, you hardly see a soul on the walk through the forest. En route you pass to Þingvallavatn, Iceland’s largest lake, which is good for birdwatching.

Starting point: Northern visitors centre (which has an excellent collection of (natural history) books). From the northern visitors' centre, drive down the 361 to Þingvellir, take after 1.2 km the right branch on the Y-junction and park after 400m on the first car park on your tightthe Vallakrokur car park.

Walk 1 – Trough historic Þingvellir (45 minutes – easy)

Follow the trail from the car park, go left and after 500m, cross the bridge. You are now crossing one of the faults of the Þingvellir plain – a cleft that formed as Eurasian and American tectonic plates pulled apart. There are several of these faults, which are technically the land in between the plates. Many people have thrown coins into the deep and clear water here.

One of the faults of Þingvellir where the earth's crusts cracked as the tectonic plates pulled apart.

Continue. This wide trail is the site of historic Þingvellir. This is where the settlers came to camp and where the law was settled. There are various stops with signs clarifying the particular points of interest. The trail also forms the main division between the plates. To your right, on the other side of the cliff, lies, geologically speaking, North America. Eurasia lies on the left side of the valley.

Note the rich vegetation on the cliffs here. Among the many species, Beech Fern, Alpine Woodsia and Roseroot stand out. There are a few Frog Orchids too.

Follow the trail all the way up to the southern visitors’ centre, which has an exhibition on the area's history and geology.

Return and take the first trail to the right, which brings you across the ridge and down to the river. Cross the bridge.

T he area around the bridge can be interesting for birds. Look for Greylag Goose, Red-breasted Merganser and Red-necked Phalarope on the river and listen for the chattering calls of the Redpolls around the trees.

Follow the trail to the left directly after the bridge and walk past a small church. Either follow the left road back to the car park, or, for the longer walk, take the right road to another car park and from there on to the road. Go left and after a few metres, turn right onto a small path, marked with the sigh 'Gönguvegur.

This trail, much quieter than the busy trails to the historic site, leads through lovely stands of Kjarr – the Icelandic natural copse of Birch and Tea-leaved Willow. The undergrowth consists mostly of Dwarf Birch, Heather, Bearberry, Bog Bilberry, Crowberry and Northern Bedstraw. The track itself runs over beautiful patches of ropey lava, with their rippled surfaces caused by the slow solidification of very thick, viscous lava that originated from Skjaldbreiður – the wide shield volcano that lies to the north. Along the way, you cross another fault in which Beech Fern has found shelter.

After 2.2 km you come to the ruins of the old farm Skógarkot. From here you have an excellent overview of the surroundings, with Þingvallavatn to the south and the Skjaldbreiður shield volcano to the north.

Continue following the Skógarkotsvegur to Vellankatla.

This stretch is similar to the previous one. Keep an eye open for Redpoll and Merlin – the latter may suddenly turn up in pursuit of passerine birds. Close to the road, you pass a lake where Tufted Duck is common, but look for Slavonian Grebe as well.

On the road, turn right. You pass a small bay of the Þingvellirvatn. Directly thereafter, turn left onto a track with the sign 'Nes - Nautatangi'. After a small car park it continues as a track along the lakeshore.

Þingvallavatn is Iceland's largest lake and has a special ecology. It is part of the tectonic boundary zone and fed by spring water. As a result it is rich in nutrients and full of fish and invertebrates. Biologists are studying the process of speciation of Arctic Char in this lake. The chars are gradually evolving into separate species.

The birdlife of Þingvallavatn is equally rich. Red-breasted Merganser is common and both Red-throated and Great Northern Diver can be found. The small coves and pools on the lakeshore have many breeding Red-necked Phalarope. Scenically, the lakeshore is also attractive, with the lakeshore rocks covered in bright-green mosses.

The path returns to the main road. Turn left. You can make another loop along the lakeshore by following the next track to the left,, which also returns to the road, which ecentually brings you back to Þingvellir from where you walk back to the car park.

The trail through Þingvellir is paved with beautiful chunks of ropey lava.

White-beaked Dolphins are frequent in the West Fjords. On the way over to Hornstrandir, you make a good chance to see them.

The uninhabited peninsula of Hornstrandir is the northernmost part of the West Fjords and a wonderful place to visit. You can’t get there overland as the Drangajökull blocks access, but it is easy to arrange a boat trip from Ísafjörður. Ask the tourist office for details. There are various small campsites on Hornstrandir and it is well worth spending a few days there (arrange your pick up with the boat company).

Hornstrandir, a nature reserve, is a special part of Iceland for several reasons. Firstly, it is green and full of wildflowers. All farmers left the area with their sheep in 1964 and today the vegetation is recovering. There are no roads and although the farms are still there, there is no permanent habitation. A few farms now serve as summer houses. Apart from the peace and quiet, Hornstrandir has the largest population of Arctic Foxes of Iceland and they are quite easy to see. Unlike in the rest of Iceland, the Arctic Foxes are protected on Hornstrandir. Another big draw are the tall cliffs of the Hornbjarg and Hælavíkurbjarg which house the second and third-largest seabird cliffs of the country (after Látrabjarg).

Perhaps the best place to base yourself is in in Hornvík, the bay that separates both birdcliffs and where Arctic Fox can also be seen. There are two basic campsites and a bunkhouse where you can sleep when you bring your own sleeping bag.