Spanish Pyrenees

CROSSBILL NATURE GUIDES

Spanish Pyrenees

WILDLIFE

LANDSCAPE

FLORA AND FAUNA ROUTES AND SITES

BIRD WATCHING

Dirk Hilbers – Kees Woutersen

Crossbill Guides: Spanish Pyrenees – Spain

First print: 2012

Second print: 2016

Third, fully revised print: 2025

Initiative, text and research: Dirk Hilbers, Kees Woutersen

Editing: John Cantelo, Brian Clews, Cees Hilbers, Riet Hilbers, Niels de Haan, Kim Lotterman, Gino Smeulders, Albert Vliegenthart

Illustrations: Chris Braat

Maps: Dirk Hilbers / mapy.com

Type and image setting: Oscar Lourens

Print: ORO grafic projectmanagement / PNB Letland

ISBN 978-94-91648-39-7

This book is made with FSC-certified paper. Instead of compensating the CO2emissions of the printing process, as we usually do when making a Crossbill Guide, we’ve chosen to invest that money in nature conservation. You can find details of the project we’re supporting on our website, under ‘Downloads’ on the Spanish Pyrenees guidebook page.

© 2025 Crossbill Guides Foundation, Arnhem, The Netherlands

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form by print, photocopy, microfilm or any other means without the written permission of the Crossbill Guides Foundation.

The Crossbill Guides Foundation and its authors have done their utmost to provide accurate and current information and describe only routes, trails and tracks that are safe to explore. However, things do change and readers are strongly urged to check locally for current conditions and for any changes in circumstances. Neither the Crossbill Guides Foundation nor its authors or publishers can accept responsibillity for any loss, injury or inconveniences sustained by readers as a result of the information provided in this guide.

Published by Crossbill Guides in association with KNNV Publishing.

crossbillguides.org knnvpublishing.nl saxifraga.nl

CROSSBILL GUIDES FOUNDATION

This guidebook is a product of the non-profit foundation Crossbill Guides. By publishing these books we want to introduce more people to the joys of Europe’s beautiful natural heritage and to increase the understanding of the ecological values that underlie conservation efforts. Most of this heritage is protected for ecological reasons and we want to provide insight into these reasons to the public at large. By doing so we hope that more people support the ideas behind nature conservation. For more information about us and our guides you can visit our website at: crossbillguides.org

Highlights of the Pyrenees and steppes of Huesca

Search for the special birdlife of the high Pyrenees starring such avian delights as Wallcreepers, Lammergeiers and Citril Finches (routes 9, 13, 15, 16 and site C on page 203).

Walk the dramatic glacial gorge of Ordesa – one of the most awe-inspiring landscapes of Europe (route 15).

Watch wild vultures fight over a carcass at one of the comederos or vulture feeding stations in the Sierra de Guara (D on page 162). 1 2 3 4

Take long walks through pristine Pyrenean meadows and along glacial lakes and marvel at the wealth of wildflowers and butterflies (e.g. routes 18, 19).

Embrace Huesca’s alternative nightlife and see Foxes, Beech Martens, Red-necked Nightjars and owls along the minor roads in Dépresion del Ebro.

Examine the endemic flora of the cliffs and rock faces of Añisclo and Alquézar (routes 8 and 17).

8

Go south into the Monegros and watch flocks of sandgrouse before a rising sun with a supporting choir of the rare Dupont’s Lark (routes 2 – 5).

Be surprised at how many ways the earth’s surface can be sculpted into the oddest towers, pillars, cliffs and caves (e.g. routes 5, 6, 15 and 17).

About this guide

This guide is meant for all those who enjoy being in and learning about nature, whether you already know all about it or not. It is set up a little differently from most guides. We focus on explaining the natural and ecological features of an area rather than merely describing the site. We choose this approach because the nature of an area is more interesting, enjoyable and valuable when seen in the context of its complex relationships. The interplay of different species with each other and with their environment is astonishing. The clever tricks and gimmicks that are put to use to beat life’s challenges are as fascinating as they are countless. Take our namesake the Crossbill: at first glance it’s just a big finch with an awkward bill. But there is more to the Crossbill than meets the eye. This bill is beautifully adapted for life in coniferous forests. It is used like scissors to cut open pinecones and eat the seeds that are unobtainable for other birds. In the Scandinavian countries where Pine and Spruce take up the greater part of the forests, several Crossbill species have each managed to answer two of life’s most pressing questions: how to get food and avoid direct competition. By evolving crossed bills, each differing subtly, they have secured a monopoly of the seeds produced by cones of varying sizes. So complex is this relationship that scientists are still debating exactly how many different species of Crossbill actually exist. Now this should heighten the appreciation of what at first glance was merely an odd bird with a beak that doesn’t seem to close properly. Once its interrelationships are seen, nature comes alive, wherever you are.

To some, impressed by the ‘virtual’ familiarity that television has granted to the wilderness of the Amazon, the vastness of the Serengeti or the sublimity of Yellowstone, European nature may seem a puny surrogate, good merely for the casual stroll. In short, the argument seems to be that if you haven’t seen a Jaguar, Lion or Grizzly Bear, then you haven’t seen the ‘real thing’. Nonsense, of course. But where to go? And how? What is there to see? That is where this guide comes in. We describe the how, the why, the when, the where and the how come of Europe’s most beautiful areas. In clear and accessible language, we explain the nature of Pyrenees and refer extensively to routes where the area’s features can be observed best. We try to make Pyrenees come alive. We hope that we succeed.

How to use this guide

This guidebook contains a descriptive and a practical section. The descriptive part comes first and gives you insight into the most striking and interesting natural features of the area. It provides an understanding of what you will see when you go out exploring. The descriptive part consists of a landscape section (marked with a red bar), describing the habitats, the history and the landscape in general, and of a flora and fauna section (marked with a green bar), which discusses the plants and animals that occur in the region.

The second part offers the practical information (marked with a purple bar). A series of routes (walks and car drives) are carefully selected to give you a good flavour of all the habitats, flora and fauna that Pyrenees have to offer. At the start of each route description, a number of icons give a quick overview of the characteristics of each route. These icons are explained in the margin of this page. The final part of the book (marked with blue squares) provides some basic tourist information and some tips on finding plants, birds and other animals.

There is no need to read the book from cover to cover. Instead, each small chapter stands on its own and refers to the routes most suitable for viewing the particular features described in it. Conversely, descriptions of each route refer to the chapters that explain more in depth the most typical features that can be seen along the way.

In the back of the guide we have included a list of all the mentioned plant and animal species, with their scientific names and translations into German and Dutch. Some species names have an asterix (*) following them. This indicates that there is no official English name for this species and that we have taken the liberty of coining one. We realise this will meet with some reservations by those who are familiar with scientific names. For the sake of readability however, we have decided to translate the scientific name, or, when this made no sense, we gave a name that best describes the species’ appearance or distribution. Please note that we do not want to claim these as the official names. We merely want to make the text easier to follow for those not familiar with scientific names. An overview of the area described in this book is given on the map on page 15. For your convenience we have also turned the inner side of the back flap into a map of the area indicating all the described routes. Descriptions in the explanatory text refer to these routes.

Icons

Birds

Reptiles / amphibians

Butterflies

Dragonflies

Invertebrates

Route 13: San Juan de la Peña and Oroel

Route 14: The Hecho Valley

Route 15: The Tena Valley and El Portalet

Route 16: The Valley of La Sarra

walks and sites in the western valleys*

National Park Ordesa and Monte Perdido

Route 17: The Ordesa Canyon

Route 18: Bujaruelo and the Otal valley

Route 19: The Añisclo Gorge

Route 20: Escuaín

Route 21: Revilla – The Lammergeier Trail

Route 22: The Pineta Valley

things to do in Ordesa*

Benasque: the eastern valleys

Route 23: El Turbón

Route 24: Benasque

Route 25: The high mountain lake of Llauset

*The names and locations of the additional sites are shown in the map in the back cover.

LANDSCAPE

Introduction

The Pyrenees are both lush and bleak, dramatic and gentle. The mountainous character of the landscape is sharpened and thrown into relief by its stark desert-like southern hinterland. It is this combination that makes this region such a popular destination for naturalists. You will immediately understand why this is so from the first moment you set foot here. The lofty cliffs are overwhelming and the distant snow-covered peaks add a mysterious allure.

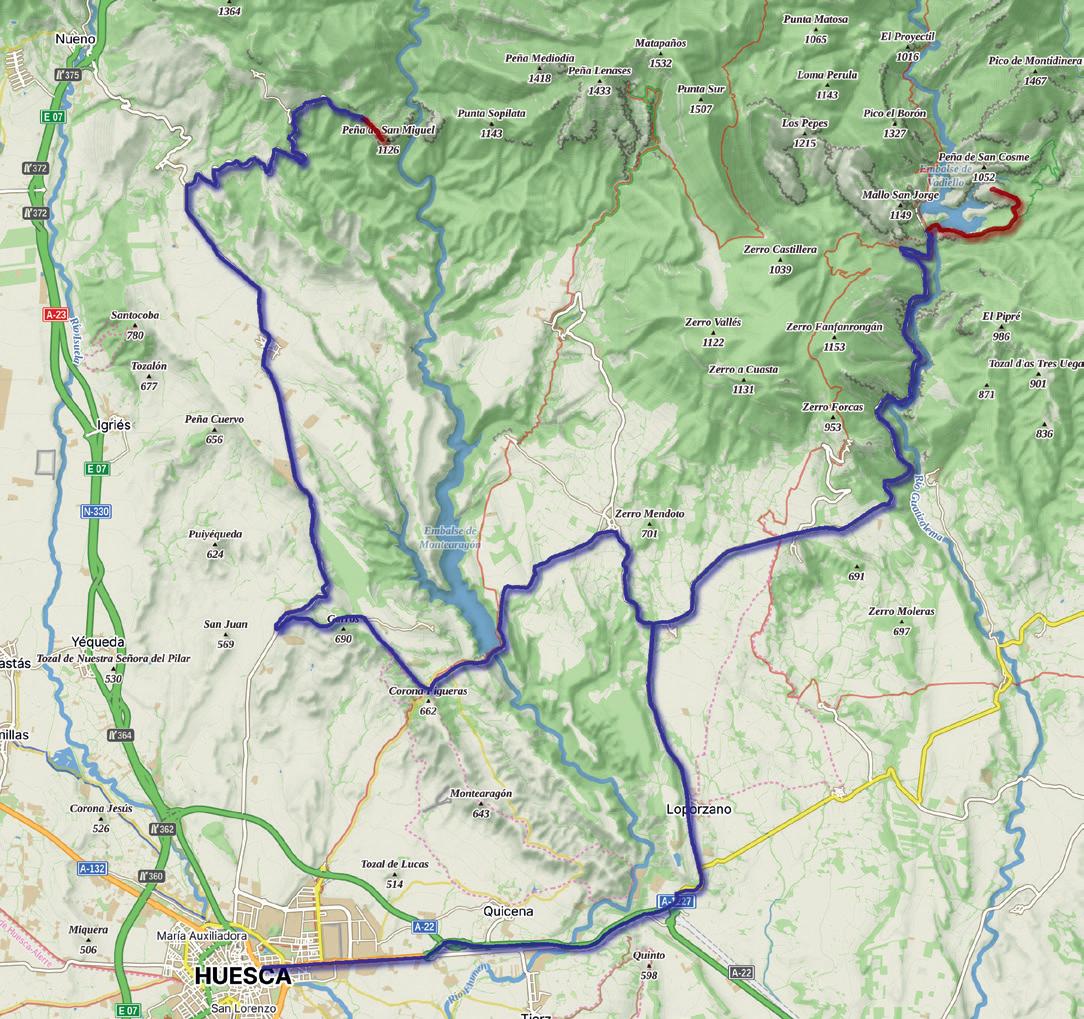

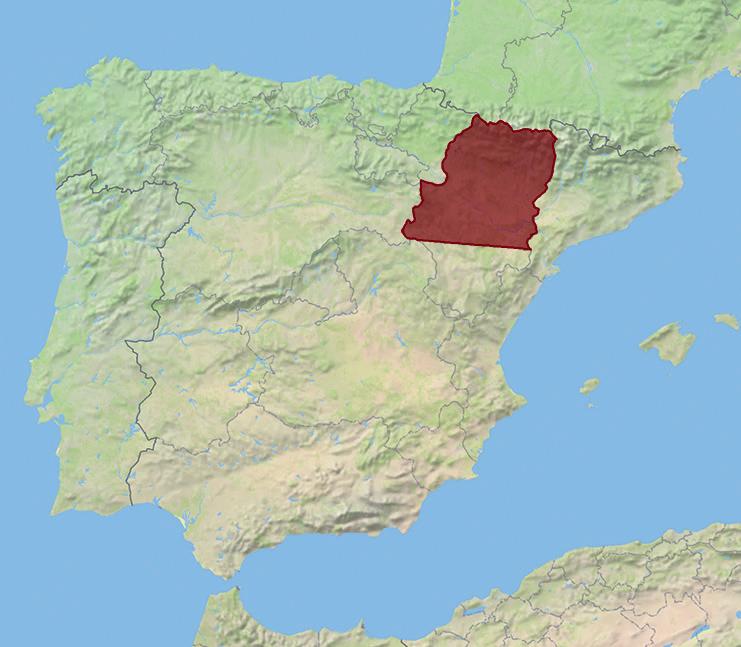

The wildest and most scenic parts of the Spanish Pyrenees are found in the Province of Huesca, the area of this guidebook. This region is characterised by its abrupt landscape with countless cliffs of several hundreds of metres high, which make large parts quiet and inaccessible – one of the reasons that there is so much wildlife here.

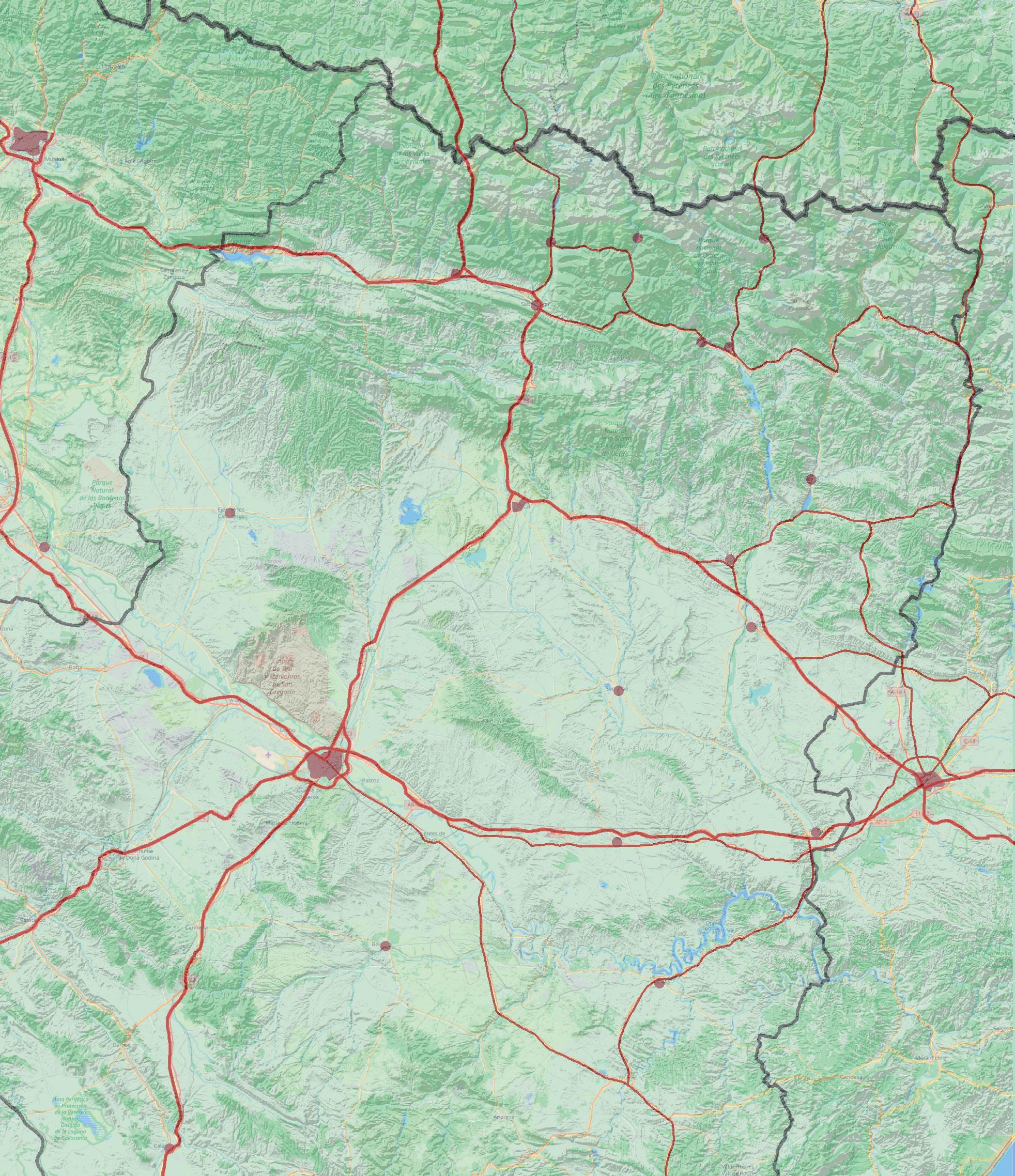

If one had to summarise the area in a single word, it would be ‘variability’. Climate, landscape, flora and fauna change dramatically over short distances. It is only a little over 100 km from the snow-capped mountains on the border with France to the arid, semi-desert lowlands of the basin of the river Ebro. From cold, barren conditions at 3,000 metres, you can move down through fresh Alpine meadows, then on into dense mountain woodlands then further down into Mediterranean evergreen oak woods and scrub and eventually, onto steppe and desertlike terrain (around Zaragoza). From the city of Huesca, each of these habitats can be reached within an hour – an exceptionally swift transition of the landscape.

This varied landscape translates into a rich flora and fauna. And since most areas, including those without any protection, are still in good condition, you can expect to find interesting things just about anywhere. However, for a more focused and informed exploration of the Pyrenees and steppes of Huesca, you need a little background knowledge. And that is where this guide comes in.

Massive Beech trees grow deep down in the damp gorges of the Pyrenees.

Geographical overview

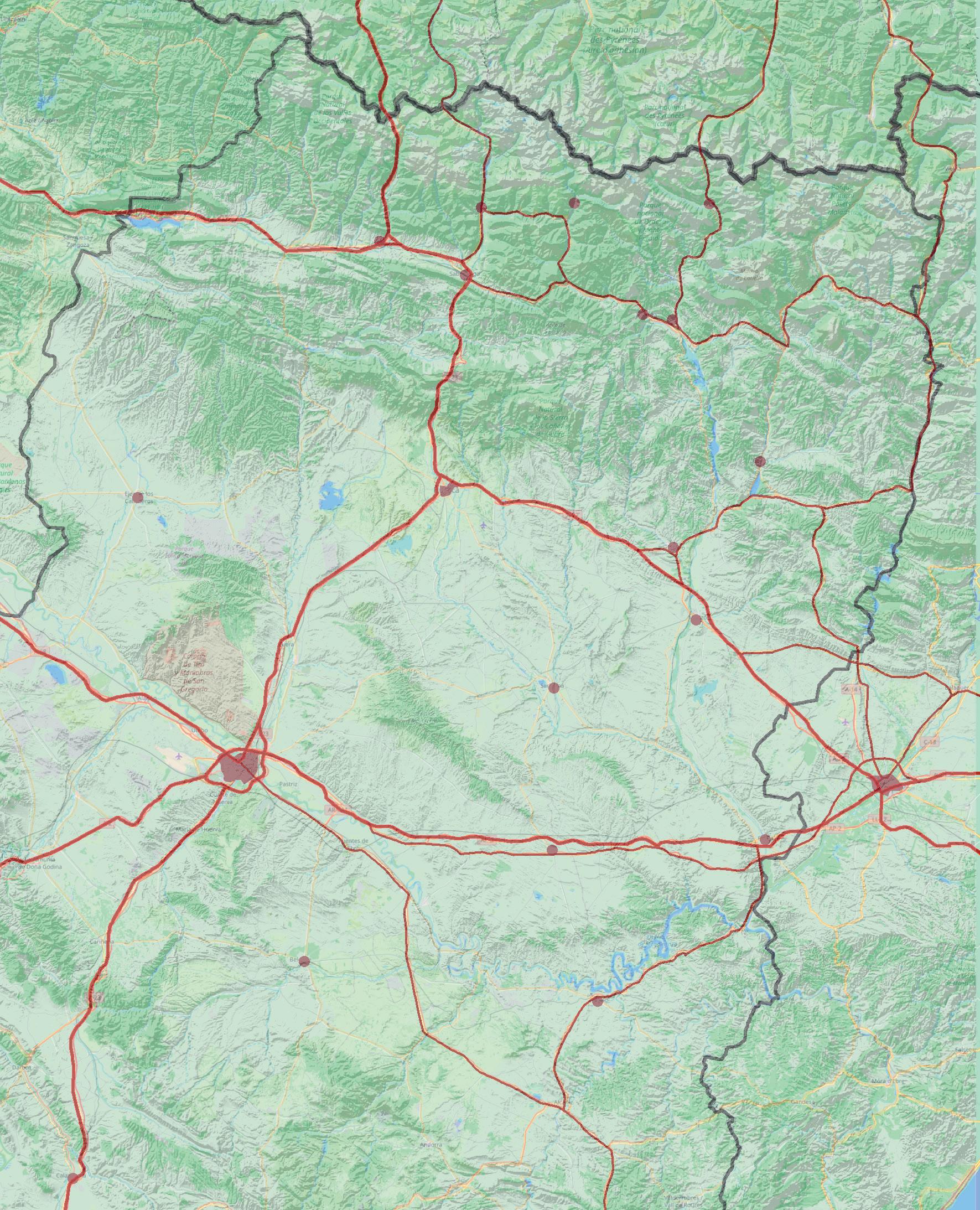

The area described in this book covers the province of Huesca and a few sites directly adjacent in the province of Zaragoza. Both provinces form, together with Teruel province, the autonomous region of Aragón. Our region can be divided in three parts of about the same size. Each of these areas are strikingly different in landscape, ambiance, climate, flora and fauna.

The Ebro basin: Somontano and Monegros

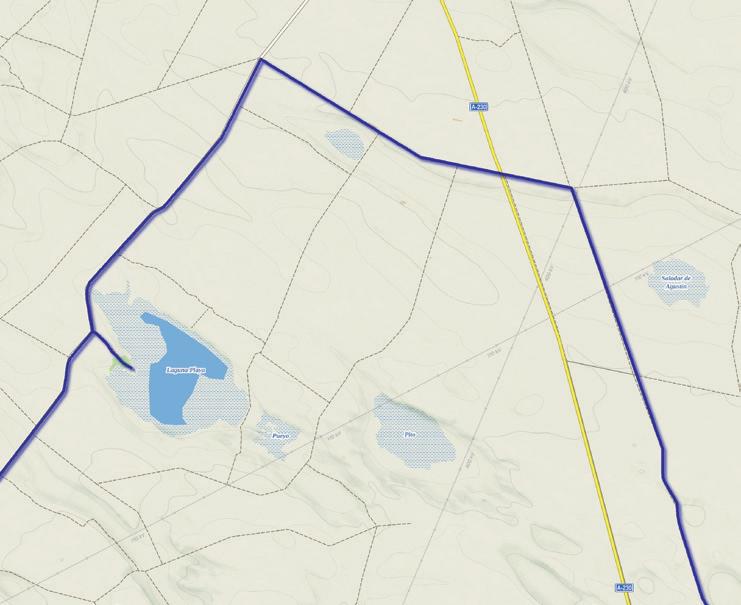

The relatively flat and low land surrounding the Ebro and its tributaries is known as the Ebro basin. In Huesca, it is divided in the Somontano and Los Monegros . Route 2 to 6 cover territory in this area.

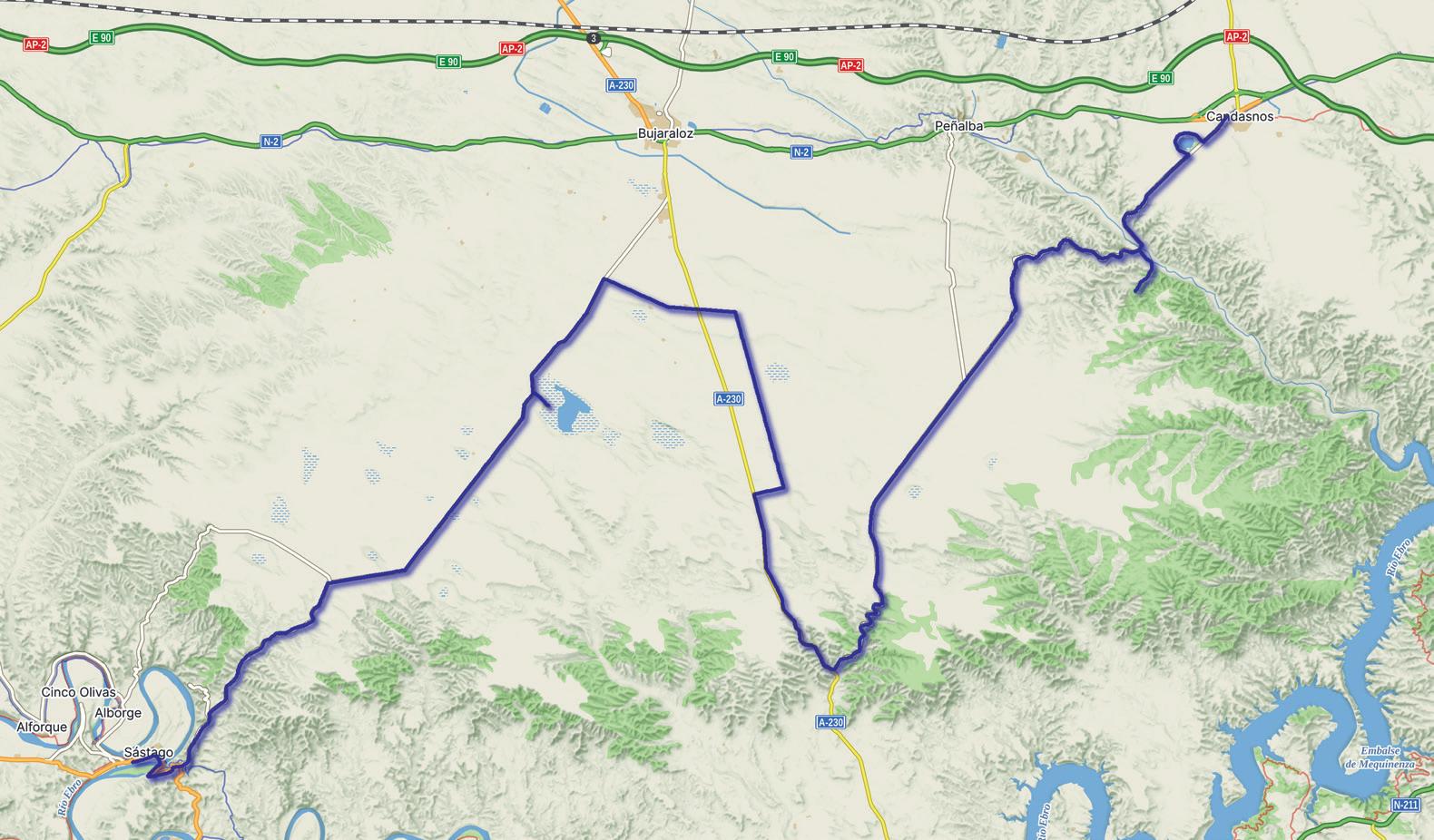

Somontano, literally means ‘land under the mountains’, and is the green and picturesque strip just south of the Sierras Exteriores . The important cities of Huesca and Barbastro are situated in the Somontano. Travelling south from here (as route 5 does), the landscape gradually becomes more arid as one enters the Monegros. The Ebro river is the life line in this dry region and supports the large city of Zaragoza (687,000 inhabitants in 2024). From whichever direction the wind blows, the central part of the Ebro basin is always in the rain shadow of mountains. Therefore, it is a dry and hot area, in some places reminiscent of the great deserts of North America. Spectacular and thinly populated (apart from Zaragoza and its environs), this area supports some wellknown bird sites, such as the steppes of Los Monegros and south of it Belchite. On page 108 we provide a detailed account of this area as an introduction to the routes.

Sierras Exteriores

The second region is a belt of mountains collectively called the Sierras Exteriores or Prepireneos (although we won’t be using the latter term in this book). Routes 7 to 11 cover this area. The central, largest and highest part of this mountain range is the Natural Park Sierra de Guara, but other fairly famous areas, such as Riglos and Loarre, are part of this chain too.

The Sierras Exteriores are, with peaks around 2000 metres, not as high as the central Pyrenees, but nevertheless form a respectable mountain chain. The mountains rise steeply up from the Somontano and are virtually deserted. The few villages that exist are at the southern base of the mountains (Riglos, Alquézar) and along the few valleys that connect the lowlands with the high Pyrenees.

The Sierras Exteriores form a considerable geographical barrier. Traffic through the chain is concentrated to a few valleys. The main traffic route (at the time of writing being converted into a motorway) is the

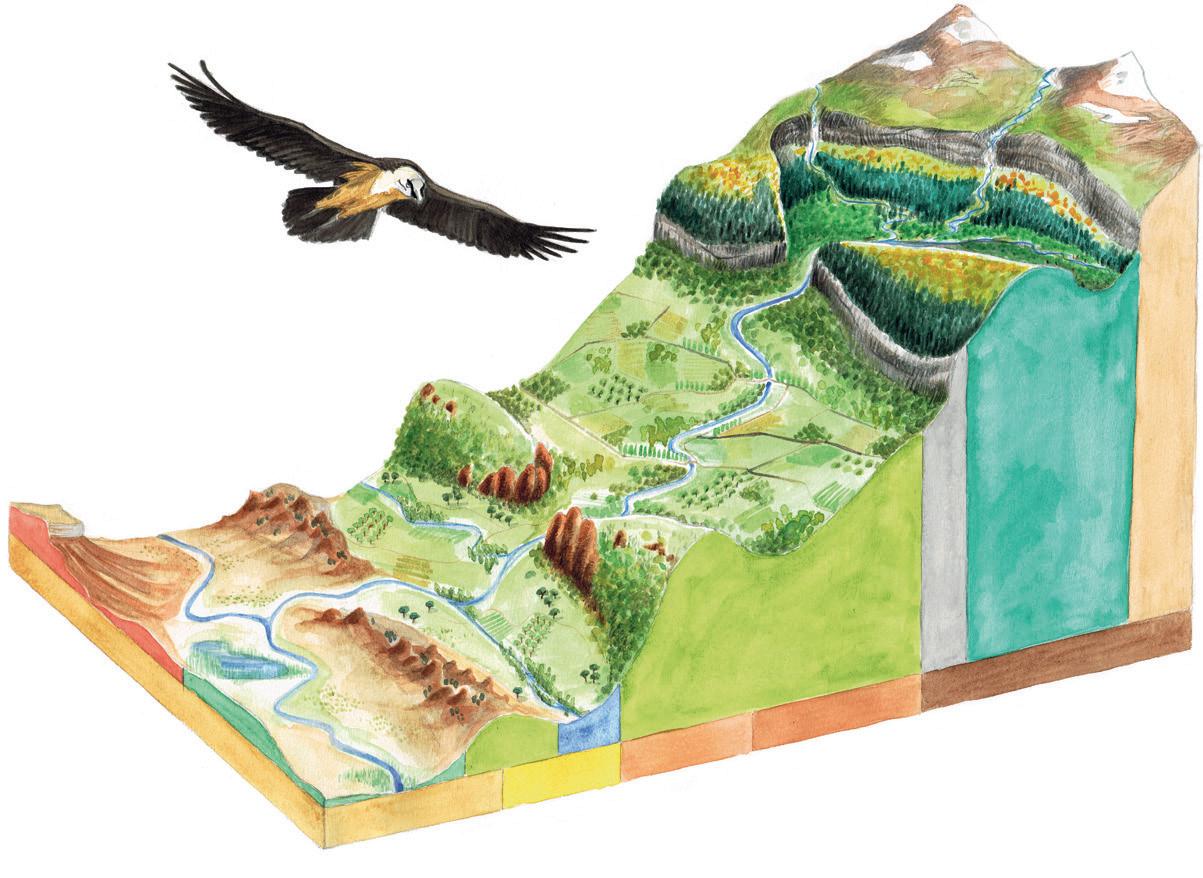

The four main landscapes of the Pyrenees: the steppes of the Ebro basin, the green Somontano, the Mediterranean Sierras Exteriores and the Alpine landscape of the high Pyrenees.

Opposite page:

Overview of the area covered by this guide book.

A23 which connects Huesca with Sabiñánigo. Towards the west there is only the road that connects Ayerbe with Jaca (via, with a small diversion, the village of Riglos). East of Huesca the next option to cross the Sierras Exteriores is near Alquézar at the far eastern end of the Sierra de Guara. East of Barbastro, the Sierras Exteriores disintegrate into a series of smallermountain ranges, pierced by larger rivers that run down from the Pyrenees, like the Cinca, Esera, Isábena and Ribagorzana. Beside these rivers, north-south traffic is much easier.

On page 140 we provide a detailed account of this area as an introduction to the routes.

Depresión and High Pyrenees

The third region lies north of the Sierras Exteriores and stretches out to the French border. Routes 12 to 21 cover this region. It is a large area with hills and smaller mountains, intersected with broad valleys separating the main Pyrenean chain and the Sierras Exteriores . This is known as Las Depresiones. Most of the Pyrenean towns, such as Jaca, Sabiñánigo, Fiscal, Aínsa and Campo, are here.

Broad shallow rivers, small areas of agriculture and vast areas of rocky hillsides covered in scrub and Portuguese Oak woodlands dominate the landscape. Only locally are there larger mountains of which the isolated twin mountains of San Juan de la Peña and Oroel (route 12) are the most noteworthy.

The High Pyrenees themselves rise up north of a line drawn between Jaca, Aínsa and Campo. Alternating valleys and mountains, orientated north-south, connect with the central Pyrenean ‘spine’ that runs all along the border with France. This is the highest part of the Pyrenees (see page 16).

Due to this topography, a visit to the High Pyrenees always takes one of these north-south valleys. Each has its special character and they are, therefore, separately described in this book. In general the western valleys (Ansó, Hecho, Canfranc) are the most ‘Atlantic’ (meaning that they are relatively green and moist). The eastern valleys (Plan, Benasque and Barrabés) are more ‘Mediterranean’, thus drier and sunnier (although not necessarily warmer). In the centre lie the great massifs of the National Park Ordesa and Monte Perdido, both of which, being limestone, have a more dramatic character of massive gorges and impressive cliffs.

On page 162 we provide a further account of the Depresión and High Pyrenees as an introduction to the routes in this area.

Fog is frequent in winter, but, like most weather types, local. Usually the lowlands experience fog (such as here the Depresión) and the mountains are clear.

The climate in the Ebro valley is a Mediterranean one although with a distinct continental slant. Winters, which reign supreme until the end of March, are much colder than at the coast. The strong winds over the open plains make it even colder. The cold cierzo blows from the northwest and the warmer bochorno from the east, and both can build up speeds of nearly 100 km per hour. Fog is another typical feature of the lowlands in winter. Some valleys see fog regularly and there it is an important source of water for the vegetation.

But sun and clear skies are the usual conditions in the lowlands. Over much of the year, the sun relentlessly desiccates the land. The summers are extremely dry and hot. Two months without a single drop of rain is standard.

In contrast in the Pyrenees a mountain climate predominates, with precipitation possible throughout the year. Between December and March I it mostly falls in the form of snow in the valleys. On the peaks however, the snowy period extends well into spring. The dominant wind direction, north-westerly, brings moist air to the western Pyrenees (Basque and Navarra) and the northern, French slopes. In Huesca, the mountains are relatively dry. Most rain and snow falls close to the border. It is frequently the case that if one travels over the Pyrenees, it pours on the French side, rains on the border, becomes dry a few kilometres further on with the sun coming out as one enters the valley. We have never experienced differences this stark elsewhere in Europe.

In summer, clouds often build up during the day over the Pyrenees, bringing rain and sometimes thunderstorms in the late afternoon. Such rains usually don’t last long, but can be dangerous for hikers at high altitudes, particularly as the deluges are accompanied by lightning.

Habitats

Given the extreme climatic differences, it is not a surprise that there is a large range of habitats in the Spanish Pyrenees. Some habitat types reappear, in different forms, throughout the area. A heat and drought adapted forest (consisting of Spanish Juniper, Aleppo Pine and Holm Oak) occurs in the Ebro lowlands. A very different forest type, adapted to cool, moist conditions, consists of dense stands of Beech and Silver Fir, and occurs in the mountains. Cliffs and wetlands too, have their specific forms in each of the regions of the province.

Other habitats are restricted to a specific part of the province, like the steppes and semi-deserts in the Ebro basin and the Alpine meadows of the High Pyrenees.

We distinguish five general habitat types, which are described in detail in the following chapters. These are steppe and farmland (page 22), wetlands (page 26), cliffs and canyons (page 31), forests and scrublands (page 33) and high mountain habitats (page 39). These are further divided into the specific habitat types that occur at different altitudes. The illustration below gives an overview of these different habitats and their position in the landscape.

Each habitat has its own ecology, landscape, atmosphere and unique inhabitants – in other words, its own specific charm. Therefore, we have selected the routes and sites (described from page 111 onwards) to cover each of these habitats. At the beginning of each description we refer to the routes and

Cross-section of Huesca with its typical habitats.

Somontano

Ebro basin

Depresión

High Pyrenees

Mediterranean forest and scrub (page 34)

Cliffs (page 31)

Riverine woodland (page 28)

Juniper forest (page 34)

Wetlands (page 26)

Steppes (page 22)

High mountains (page 39)

Mountain forests (page 35)

Sierras Exteriores

The inaccessibility also favours birds. Mammalian egg thieves (including humans) can’t reach birds’ nests. Soaring birds like raptors take advantage of the rising air. Cliff ledges are the vulture’s equivalent of an apartment with elevator: the air warms on the vertical surface and rises. The bird only needs to spread its wings to be effortlessly wafted upwards.

This is also a reason why south-facing cliffs, quickly warmed by the sun, are more in demand than north-facing ones. Wallcreepers too prefer south-facing cliffs where their favourite prey, insects, are more abundant. Butterflies and reptiles which need the warmth of the sun to become active, are often found on south slopes too.

Plant life is also sensitive to exposure to the sun’s rays, but this time, many species prefer the shadier, moister north face, where the microclimate is generally less extreme. Ramonda or Bear’s-ear (page 63) is an obvious shade-lover, as are many ferns, like Maidenhair Fern, Maidenhair Spleenwort, Hart’s-tongue and Smooth Spleenwort. On the sunny side of the rock, drought-resistant Snapdragon, Long-leaved (page 63) and Live-long Saxifrages and Sarcocapnos are typical (page 70).

The lowland rock slopes have their own distinctive set of species. Among the birds, Blue Rock Thrush and Black Wheatear are typical of lowland cliffs. The steep slopes of the table mountains are a refuge for steppe flora, because the flatter surfaces are mostly converted to agricultural use.

The Griffon Vulture is the most numerous of the three vultures of Huesca.

Forests and scrubland

Mediterranean oak woodlands are a prominent feature on routes 6, 9, 11, 12, 20 and sites A, C and F on pages 161-163. The special dry Aleppo pine and Spanish Juniper woodlands are part of route 5 and site A on page 137. Well-established mountain pine forests are to be found on routes 11, 12, 14, 16, 20 and site D on page 203. Beech and beech-fir forests of the moist areas of the Pyrenees feature on routes 13, 15 and 18 and site E on page 182, whereas subalpine open pine heathlands are present on routes 14, 15, 19 and site D on page 203. Route 17 is all about canyon forests.

Before the arrival of humans, the larger part of Huesca was forested. Only the saline and gypsum soils, areas where rocks surface, and the regions above the treeline are naturally forest-free. In comparison to many other regions in Spain, Huesca has retained a fair chunk of its forests. With the exodus of people from the mountains (see history section), forest cover has increased over vast areas. Woodland occurs in inaccessible places and often isn’t managed nor serves any particular purpose. In fact, apart from the odd hunter or rambler, no one sets foot in many of these areas. Large parts of the forest have developed into a natural state.

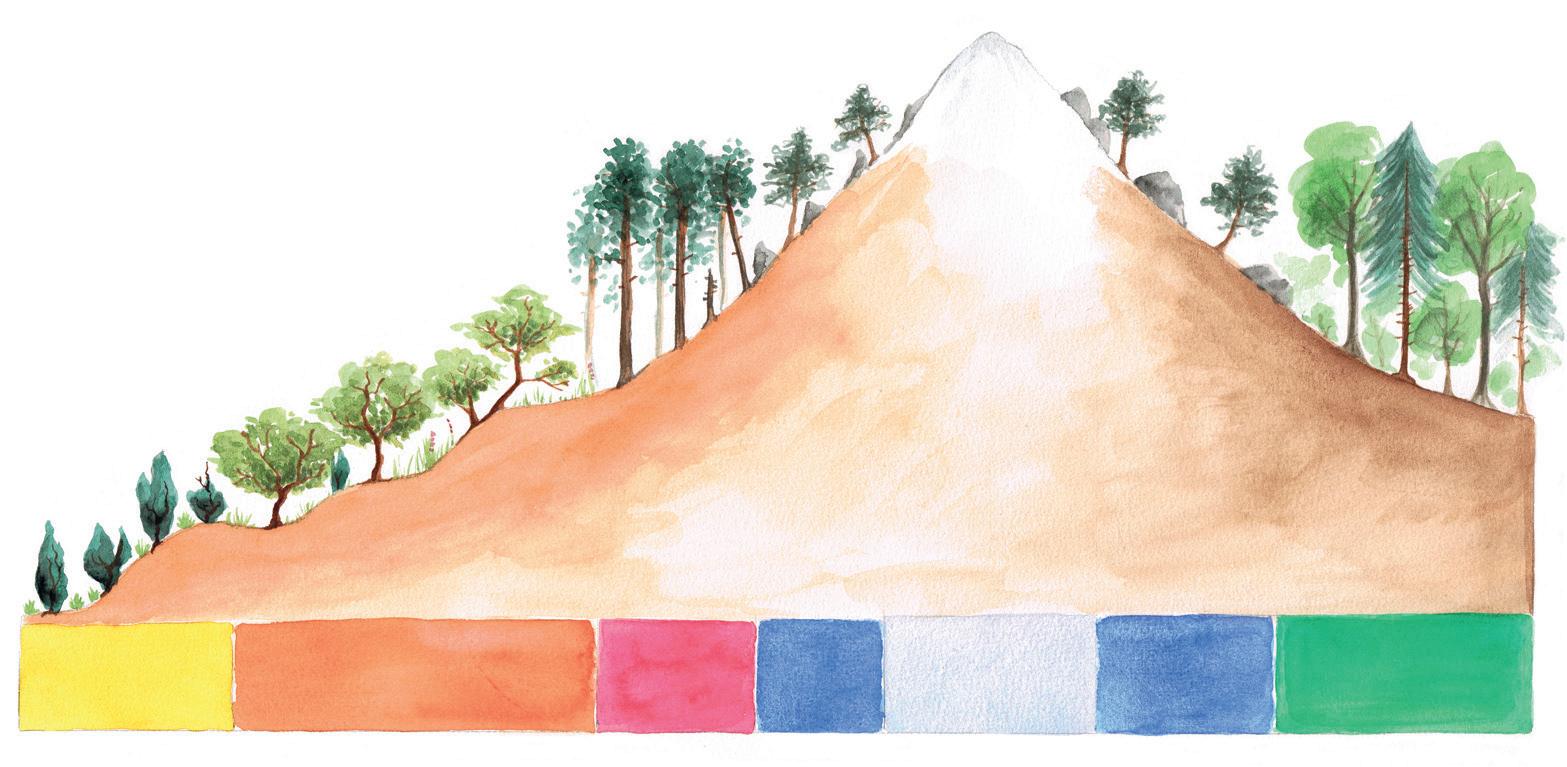

The large range of climates in the region gives rise to many different forest types, ranging from subalpine, open pine forests, mountain woodlands of Beech and Fir, Scots and Austrian pine forests, Mediterranean oak forests and drought-resistant stands of Aleppo Pine and Spanish Juniper.

Different types of scrubland and forest are found at different altitudes. Spanish Juniper forest covers the driest soils (see site A on page 137). Oak woodlands cover much of the Somontano and Depresión (e.g. routes 9 and 12). Scots Pine forests dominate the sunny areas of the mountains (e.g. routes 11 and 12), while Pyrenean Pine is found on the high slopes (e.g. route 15). In shady areas, mixed Beech-Fir forests are frequent (e.g. routes 13 and 15).

Spanish Juniper Portuguese and Holm Oaks Scots Pine Pyrenean Pine Alpine meadows

Pyrenean Pine Beech and Silver Fir

The Blue Aphyllanthes is a conspicuous flower of Mediterranean scrublands and woodlands in May and June.

Forest or scrubland?

The lowland forests are strikingly different from those of the mountains and those of temperate and northern Europe. Trees are not as tall, are more widely spaced and much more scrubby than what most would consider a typical forest.

There is debate among ecologists about how dense the original forest canopy was in the Mediterranean range. The general consensus is that, although there is now much more scrub, scrubby areas have always existed in ancient woodlands.

Scrub appears after forest fires and when grazing is less intense or stops. In the Mediterranean climate, particularly on poor and rocky soils, tree growth is very slow, so scrubland persists for many years before gradually giving over to forest. Higher up in the mountains, the combination of winter cold and poor soils has the same effect. Since forest fire is a natural phenomenon, scrubland has always been a component of Mediterranean woodland. This also is evidenced by its flora and fauna. Scrublands have evolved their own specialised set of inhabitants.

Oaks, Pines and Junipers – Mediterranean forests

The rocky sandstone hills in the Depresión, the lower reaches of the Guara and the isolated sierras in the upper Ebro basin are covered in scrubby oak woodland, locally known as carrascal. The carrascal once covered the larger part of the Aragonese lowlands before the arrival of agriculture and, in the Aragonese Province of Huesca, it still does.

In the Depresión and Somontano, Portuguese and Holm Oak dominate the woodlands, but it is locally mixed with or replaced by (planted) Austrian and Scots Pine. The woodland’s canopy can range from very open to completely closed. In the open patches a thick scrub of Kermes Oak, Rosemary, Box and other shrubs dominates. The trees and shrubs are adapted to withstand drought, heat and poor soils.

Unlike the forest in central Europe and the woodlands higher up in the Pyrenees, trees keep their leaves in winter (and are thus evergreen). The trees are fairly short with small, leathery leaves, both adaptations to the environment. Because the winters here are not very cold, there is no need to shed the leaves. This is a great advantage because no valuable nutrients are wasted. Thick wax layers protect the leaves from water loss in the summer and give these woods a more

dusty appearance than the name ‘evergreen forest’ might suggest.

The Carrascales are excellent sites to search for wildflowers in spring. There are many different species to be found, including a large variety of orchids. The exact species composition depends on the local climate and soil type. Blue Aphyllanthes (facing page) is often a common species on limestone soils. It is an inconspicuous and grass-like member of the lily family when not in bloom, but very showy when it opens its bright blue flowers. The scrublands and evergreen forests are home to a fauna that is very different from that of northern and montane forests. Mediterranean species dominate, such as Bonelli’s Warbler, Cirl Bunting, Hoopoe, Short-toed Eagle and Scops Owl. The open scrublands are also frequented by Mediterranean warblers, such as Sardinian, Dartford, Subalpine and Orphean.

Deeper down into the dry lowlands, the oaks disappear and make way for a similarly scrub-rich open woodland. Ecologically it functions roughly the same, but plants are even better adapted to drought. Coniferous plants now take a lead role, with dusty Aleppo Pine woods and bushes of Phoenician and Spanish Junipers. The largest areas with this habitat type are found in the Sierra de Alcubierre in the south of the province (site A on page 137).

Pine, Fir and Beech – the forests of the mountains

Higher up the slopes, winters are too cold and moist for evergreen trees and a mixed forest of coniferous and deciduous (leaf-shedding) trees becomes the dominant vegetation. On the dry south-facing slopes, Scots and Austrian Pines are the most frequent trees, whilst the cooler north slopes are covered in dense forests of Beech and Silver Fir. These beech-fir forests are enchanting places: green, cool and mossy, with massive trees and dotted with big boulders carpeted with saxifrages and Ramonda, a pretty, endemic species (page 63). From a Spanish perspective, where ‘hot-and-dry’ is the norm, the cool mountain forests are something special. For northern Europeans familiar with the extensive beech-fir forest of the central European hills and mountains, this zone in the Pyrenees may, at first, appear less exotic. But many of the

Holm Oaks dominate the Mediterranean forest, but in between you’ll discover a high diversity of shrubs and small trees in this woodland type.

Pyrenean Germander

Teucrium pyrenaicum

Prostrate germander with typical cream and purple flowers.

Range: mountains of northern Spain and southern France

Flowering time: June-August

Habitat: rocks, cliffs, roadsides

Frequency: fairly common

Routes: 12, 13, 14, 15, 17, 18, 20, 21

Pyrenean Iris Iris latifolia

A stunning deep purple iris that forms large drifts.

Range: endemic to the Pyrenees and Cantabrian mountains

Flowering time: July

Habitat: fresh mountain meadows

Frequency: fairly widespread and abundant

Routes: 14, 15, 16, 18, 19

Pyrenean Fritillary

Fritillaria pyrenaica

Pretty small fritillary of species-rich grasslands.

Range: Pyrenees and Cévennes

Flowering time: late May-June

Habitat: alpine meadows

Frequency: local but abundant where present

Route: 14

Pyrenean Lily

Liliumpyrenaicum

Large lily of the Martagon Lily group but with yellow flowers.

Range: northern Spain and Massif Central (where very rare)

Flowering time: June-July

Habitat: open woods, roadsides

Frequency: local and rare

Routes: 18, site A on page 202

Long-leaved Butterwort

Pinguicula longifolia

Pale-flowered Butterwort with long, yellowish leaves.

Range: Iberian mountains

Flowering time: April-July

Habitat: wet limestone rock faces

Frequency: local but abundant where present

Routes: 15, 16, 17

Pyrenean Yam Borderea pyrenaica

Member of the tropical Dioscorea family.

Range: Pyrenees

Flowering time: January-April

Habitat: rocky forests, old walls

Frequency: very local and rare

Routes: 15, site B on page 202

Long-leaved Saxifrage Saxifraga longifolia

Superb saxifrage with stiff rosette and large inflorescence with hundreds of flowers.

Range: mountains of northern Spain

Flowering time: May-early August

Habitat: exposed rocks, cliffs

Frequency: widespread and common

Routes: 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 17, 20

Ramonda Ramonda myconi

Relict species from the Tertiary period, isolated member of the tropical Gesneria family.

Range: Pyrenees and Catalonian mountains

Flowering time: May-August

Habitat: sheltered, moist, shady rocks

Frequency: widespread and common

Routes: 8, 9, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20

This skull is the only remains of the Pyrenean Ibex on public display. You can admire it at the reception of the Parador de Bielsa in the Pineta valley; route 18.

The sad story of the Pyrenean Ibex

The Spanish Pyrenees has the dubious honour of producing the first global extinction of the 21st century. The century was only six days old when the last Pyrenean Ibex was found dead in Ordesa.

The Bucardo, as it was called in Aragonese, was endemic to the Pyrenees and lived on both sides of the border. It was distinct from both the Alpine and Iberian Ibexes. The males had bigger, broader horns and the females were heavier with bigger heads. Genetically, the Bucardo was midway between the Alpine and Iberian species.

Due to its impressive horns and, not least, the wild and challenging habitat in which it lived, the Bucardo was an esteemed trophy. By 1880, hunting had reduced the population to one small area in and around the Ordesa valley. In 1918 it finally received some protection with the establishment of the Ordesa National Park where it could not be hunted. But this was not enough. The upland plateaux, which provided its main summer pastures, wasn’t part of the National Park (not until 1984). From the Civil War onwards and into the 1950s, poaching in the Park took a heavy toll on the population.

Paradoxically, the establishment of the National Park itself turned out be another nail in the coffin. The valley with its harsh winter climate never was a favourable place for the Ibex. It became even less suited as new Park regulations banned tree felling and grazing, causing the valley to become overgrown with bushes, not leaving enough food for the Ibex. Sadly, the Bucardo was being preserved in the one place it couldn’t survive. Some 80 years after the establishment of the National Park, there were only ten to twenty animals left.

Shortly after Spain joined the European Union, an active Bucardo conservation plan was launched. By the start in 1993, there were three females left, but no males (the last male died in 1991). The plan was to crossbreed the Pyrenean females with males from the Iberian Ibex, as a last attempt to save the species, but to no avail. One female died after nine months in captivity, another female just disappeared and the last was found dead under a tree on the 6th of January 2000. More information: bucardo.es.

Birds

The best routes for high mountain birds are routes 13, 15, 16 and 21. Vultures and other cliff breeding raptors are very visible on routes 7, 9, 10, 12 and 15, plus sites A, C and D on pages 161-162 and sites B and C on pages 202-203. Mediterranean birds are more scattered, and are often found alongside the road (sites A on pages 137 and 161). Rewarding routes are 3, 5, 6, 8, 9, 10 and 11. The best sites for steppe birds are on routes 1, 2, 3 and 4. Wetlands birds are present on routes 1, 3, 5 and 6. A detailed per species site description is given on page 226.

The Spanish Pyrenees became, together with places like the French Camargue, one of the first popular birdwatching destinations abroad. Before travel by airplane became something for the masses, the Pyrenees was one of those magical places where a large number of ‘new’ species (to the predominantely ‘northern’ observers) could be seen in an area that could still be reached conveniently within an average holiday period. The quantity and variety of birds plus the spectacular, undisturbed landscape was legendary. Today, cheap fly-drive package deals create more competition with other areas, but the Spanish Pyrenees, together with the nearby steppes, remain as they were: an exceptionally rich birdwatching destination. Moreover, the presence of many good hotels and camp sites and increased accessibility, now make travel a lot more comfortable. There is a high diversity of birds, which can be broadly grouped into five ‘domains’. First, there are the mountain specialists, most of which occur at altitude (e.g. Rock Thrush, Snowfinch). Then there is the rich birdlife of Mediterranean scrub, agricultural land and open woodlands (e.g. Bee-eater, Woodchat Shrike). And third, there are the arid landscapes of the Ebro basin with its bustards and sandgrouse.

Raptors in general and vultures in particular make the Pyrenees a spectacular place for birdwatching.

The three vultures of the Pyrenees: the Bearded (top), the Griffon (previous page) and the Egyptian Vulture (bottom). A fourth species, Black Vulture, extinct here for over 100 years, is now the subject of a re-introduction project.

These, the first three of our five domains, provide the greatest attraction to visiting birdwatchers. The two others, although arguably less exciting, greatly add to the overall diversity. The fourth domain encompasses the extensive forests and fresh meadows of the Pyrenees, which support a large variety of temperate European species. Familiar they may be, but here in Spain some of them reach their southern limit (e.g. Song Thrush, Marsh Tit). Finally we come to the wetlands (with species such as Red-crested Pochard and Little Bittern). Huesca being land-locked, arid and mountainous, wetland is not the first habitat that comes to mind. And indeed, the wetlands are limited in extent, but the number of birds is unexpectedly high. In this chapter we describe these five bird ‘domains’ in further detail.

Birds of the high mountains

The open woodland, bushes and Alpine meadows around the tree limit (between 1,600 and 2,100 metres) support many mountain species. The subalpine zone, with its scattered trees and heath and alpenrose bushes, is the haunt of Ring Ouzel and Citril Finch with a fine supporting cast of Tree Pipit, Rock Bunting, Dunnock, Yellowhammer, Linnet and Red-backed Shrike. In flat areas with tall herbs, both below and above the treeline, you may encounter two unexpected birds. This is the natural habitat of Quail and Grey Partridge. Quail is frequently heard if rarely seen. The Grey Partridge is particularly interesting as they

Cliff breeding species

High Pyrenees Sierras Exteriores Lowland cliffs

Lammergeier common common

Griffon Vulture very common abundant local

Egyptian Vulture frequent common local

Golden Eagle frequent frequent fairly common

Bonelli’s Eagle extinct rare

Peregrine frequent frequent rare

Kestrel fairly common fairly common fairly common

Crag Martin very common very common local

House Martin very common very common very common

Alpine Swift frequent frequent local

Eagle Owl rare fairly common common

Rock Dove rare fairly common

Wallcreeper frequent

Rock Thrush frequent frequent

Blue Rock Thrush rare frequent rare

Black Wheatear local frequent

Alpine Chough fairly common

Red-billed Chough very common very common fairly common

Raven frequent frequent frequent

Rock Bunting fairly common common local

are of a relict population and a distinct subspecies. Other than in the Cantabrian mountains (where this subspecies is also found), there are no Grey Partridges elsewhere in Spain nor are they found in the nearby lowlands to the north. So the isolated population of the Pyrenees has evolved into a distinct subspecies.

Rocky Alpine meadows above the treeline support in addition to the aforementioned species, also Water Pipit, Northern Wheatear, Rock Thrush, Alpine Accentor, Alpine Chough and Black Redstart (with the latter in particular in high densities). Where rocky slopes turn into a solid rockface, the birdlife changes yet again. Warmer, insect rich south-facing cliffs have a very rich community of breeding birds. This is the realm of the Wallcreeper which, like Crag and House Martins and Alpine Swift, breeds in cracks in the escarpments. The often abundant Red-billed Chough breeds on small ledges and in larger cracks in the rock. At 1,900 m and above, the Alpine Chough takes over from its redbilled cousin. Both species often feed on Alpine meadows. Other cliff breeders include Egyptian and Griffon Vultures, Lammergeier, Golden Eagle and Raven. Particularly common is the Griffon Vulture, a colonial breeder. There are colonies all over the Pyrenees, Sierras Exteriores and on cliffs deeper in the lowlands. It can be seen cruising the skies almost anywhere.

Moorish Geckos are common in old walls and buildings in the lowlands.

Both Viperine and Iberian Grass Snakes are completely harmless. Viperine Snake is the more common of the two and prefers small rivers in the lower half of the mountains and foothills.

High up in the Pyrenees, the only widespread and potentially dangerous snake occurs: the small Asp Viper. Although it rarely exceeds 60 cm in length, this species is dangerous because of its potent venom. It is easily recognised by a combination of a clear zigzag pattern on the back, a short, thick body and the characteristic vertical cat’s-eye pupils that gives it its vicious look. The Asp Viper lives in open, sunny and rocky places in the mountains up to 2,500 m. You won’t find it easily though, since it frequently hides under rocks. It is most abundant in the western valleys (Hecho and Tena – routes 13 and 14) and rare in the Sierras Exteriores .

Perhaps the most beautiful of all the snakes is the large, slender greenand-yellow Western Whip Snake. This species, widespread in France, occurs only very locally in the region (see site C on page 215).

Rare or patchily distributed species

There is a number of reptiles and amphibians that, within the area, are rare or only occur in some specific locality. The majority of them are either typical of more northern areas and occur in a few isolated spots in the mountains, or, conversely, belong to the fauna of southern Spain and cling to a few outposts in the Ebro basin. Northern interlopers include Aesculapian Snake, Western Green Lizard and Western Three-Toed Skink. Southern species are Spiny-footed Lizard, Stripeless Tree Frog, Bedriaga’s Skink, Turkish Gecko, Horseshoe Whip Snake, Lataste’s Viper, Iberian Worm Lizard and Spanish Terrapin. These live on low densities or isolated spots in the Ebro valley. The relatively cold winters here prevent them from spreading further into the region.

Insects and other invertebrates

The better alpine meadows for butterfly watching are at Hecho (route 13), Portalet (route 14) La Sarra (site E on page 182), Ordesa (route 15 and site B on page 202), Otal (route 16), Pineta (18), Benasque (route 19 and site A on page 215) and Llauset (route 21). Route 11 and 12 are excellent butterfly routes, with species of Mediterranean scrub and dry, Mediterranean-influenced mountains.

Of the overwhelming diversity of invertebrates in the region, butterflies are especially eye-catching. The colourful clouds that accompany you on your walks through the Pyrenees, are an unforgettable sight.

Butterflies

The province of Huesca is one of Europe’s top butterfly areas. Both in diversity and in quantity, the province stands out. Here in the Pyrenees, you may be forgiven for thinking you have accidentally entered a carefully designed butterfly garden. Again it is the magnificently abrupt gradient from the high Pyrenees down to the lowland steppes that create a wealth of different habitats, each with its own butterflies. At least 191 species occur in this area. Thanks to the region’s excellent accessibility, a good deal of these species can actually be found. We were able to find 130 different species in just two weeks in early July. If your main interest is butterflies, organise your trip to encompass not only different landscapes and altitudes, but also consider the soil (calcareous versus granite). The butterfly fauna can be roughly divided in three different zones: First that of the higher Pyrenees, second the Mediterranean hills and mountains (Depresión, Sierras Exteriores and Somontano) and third the steppes of the Monegros.

The Sierras Exteriores and Somontano abound in southern delights. The beautiful Striped Grayling (top) and the Escher’s Blue (bottom) fly in early July.

Cross the Ebro bridge and follow the A221 as it climbs out of the river gorge. After 2 km, stop at the viewpoint near the crossroads.

The view of the Ebro snaking through the sandstone gorges is impressive. Black Wheatear breeds at this spot and Little and Great Egret may be present on the river. During migration, there may be raptors such as Osprey. We’ve also seen Red-rumped Swallow, a rare but slowly increasing bird in this part of Spain.

Continue on the A-2105 towards Bujaraloz.

The road crosses a fine area of stony steppes. At first the terrain is still hilly, and there are plenty of places where you can stop. There may be Black-eared Wheatear, and the many stony areas have a rich reptilian fauna, with geckos (both species), Ocellated Lizard, Ladder and Montpellier Snakes.

Further ahead, you arrive on the plain, which is dry, with a mix of steppe, fallow and arable land. The small stone houses were used by workers who lived in the distant villages. There are also many piles of stones. In order to work the land, the stones were taken from the surface and placed in piles. Now, both the houses and the stone piles are occupied by Lesser Kestrel, Little Owl and reptiles. Calandra Larks are numerous in the flat plains; Short-toed Lark is also frequent.

After 17 km turn right, signposted La Playa, and stop at the deserted salt works a little ahead (the plant is a conspicuous landmark).

Measuring 3 by 2 km, La Playa is the biggest salt lake in the area. The ruins here are a reminder of the days that the salina was used to produce salt. Salt harvesting stopped in the 1930s and the storehouse and barracks fell to ruin. Jackdaws and Red-billed Choughs are now breeding here.

From the ruins you can walk a little further to a bird hide that overlooks the salt plain. Scan the lake for waders and Shelduck on migration. Kentish Plover, Lesser Short-toed Lark and Spectacled Warbler breed along the lake margins. Also scan the fields behind the lake – sometimes Great Bustards show themselves here and Montagu´s Harrier can be around. Relict Glasswort* (Microcnemum corraloides) and a score of endemic invertebrates are other highlights of La Playa. It is possible to walk around the lake (11.5 km).

Continue along A-2105 and after 3 km, take the second track to the right. Scan this area carefully. Turn left at the end of this track and turn right at the next one, which will take you to the A-230, which connects Bujaraloz and Caspe.

The cereal steppes along these tracks and on both sides of the A-230 support good populations of steppe birds. Most of the Great Bustards of Los Monegros are here. The population is estimated at only 60 individuals but the chances of finding this magnificent bird are good. It is also a favoured spot for Little Bustard, Pin-tailed and Black-bellied Sandgrouse and various other steppe species are also present. Golden Eagle and vultures frequently visit the region. In autumn, this general area is often visited by Dotterel.

Cross the A-230 and continue. Turn right at the next crossing of tracks (near a pig farm). After 6.1 km, take the second track to the right, to return to the A230 again.

This section of well-maintained tracks leads through more prime Great Bustard habitat.

The extensive cereal fields near La Playa support the last sizable population of Great Bustard in the Monegros.

Best season

April-June Of interest year round

ROUTE 10: VADIELLO AND ROLDÁN –THE GREAT GATES TO THE GUARA 75 KM + 5.5 KM WALK ONE WAY, FULL DAY, EASY-MODERATE

Spectacular cliffs with large vulture colonies. Pleasant walk through Mediterranean woodland and scrub.

Habitats: steep gorges, bare rock, Mediterranean scrub and woodland, almond groves, agricultural land, hedgehog broom scrub

Selected species Long-leaved Saxifrage, Yellow-fringed Fly Orchid*, Spanish Fritillary, Lammergeier, Griffon Vulture, Egyptian Vulture, Wallcreeper (winter), Alpine Accentor (winter), Woodchat Shrike, Alpine Swift, Rock Thrush, Subalpine Warbler, Scarce Swallowtail

The large conglomerate rocks and turquoise reservoir of Vadiello make for a surreal landscape.

Two spectacular rock formations, that of Vadiello and Roldán, form the backdrop to this magnificent route in the Sierra de Guara. At both sites, but particularly at Vadiello, there are excellent hiking options. One of these walks is described in detail here. Due to the rugged terrain, these two sites can only be reached by minor roads through the lovely and green Somontano. The scenery and the birds of prey are the most spectacular feature of this route, but there are plenty of wildflowers, reptiles and butterflies to please the all-round naturalist. From Roldán it is easy to photograph vultures in flight (photo on page 32).

Starting point: Take the N-240 east of Huesca and turn left after 4 km, in the direction of Bandaliés and Loporzano.

Follow the road through Loporzano, Sasa de Abadiado and Castilsabás.

This is typical Somontano country: fields, little areas of scrub, isolated trees and Holm Oak wood and Almond Groves. Many Black and a few Red Kites scout the fields. In May, the bright blue Beautiful Flax (p. 156) lines the roadsides. Make some stops here and there to explore the countryside. A wide variety of Mediterranean song birds breed in this landscape. One scenic stop is above the village of La Almunia del Romeral, which is the gateway into an entire different landscape: that of the Guara mountains. Look for Rock Thrush and Dartford Warbler.

Continue and park at the car park by the only hairpin on the road and walk up the small trail along the secluded stream.

Western Spectre and Common Goldenring can be seen from the trail. The grassy glades host Weaver’s Fritillary, Southern Grizzled and Lulworth Skipper. Wallcreeper winters on the steep cliff to your right. This is also the start of a strenuous, but excellent, circular trail through pine woodland scrub and along cliffs.

Continue to the dam and park. From here starts a 4 hour circular trail (easy-moderate difficulty) which is highly recommended. Follow, on foot, the signs San Cosme y San Damián.

Scan the sky and cliffs here and along the entire trail for raptors. Griffon Vultures are numerous and Egyptians are frequent, but this is also a very good site to see Lammergeier (although it is far outnumbered by the other species). In winter, the south-facing cliffs are

san julián Flúmen

Guatizalema

The La Zinca river, a site for Dipper, Sombre Goldenring Dragonfly and Large Tortoiseshell.

Return and follow the track towards the Cascadas de La Larri.

From the bridge over the cascade you can see Broad-leaved Marshorchid, Tofield’s Asphodel, Yellow Mountain Saxifrage and Largeflowered Butterwort are frequent.

Continue through fine Beech forest.

Just before crossing the Cinca river, a trail turns off to the right, signposted Lago de Marboré. It is worth following it upwards for about half an hour. After the thick Beech forest you arrive at a clearing dominated by Bracken, a large number of the superb, yellow Pyrenean Lily (p. 62) flower in June to mid-July. There is also Leafy Lousewort (p. 214) and the endemic Horned Pansy* (Viola cornuta) here. The views into the Pineta Valley from here are especially impressive. Should you continue for another hour or so on a very steep and strenuous path, you arrive in rocky terrain where Alpine Accentor and White-winged Snowfinch live.

4

Return to the main path and turn right.

3 5

After crossing the Cinca river you pass through flowery meadows with hedges and rose bushes. These meadows are superb for butterflies. Large Skipper, Small, Turquoise and Mazarine Blues, Purple Emperor, Duke-of-Burgundy and Meadow and Glanville Fritillaries are among the species we have seen here.

T he track ends near the river Cinca, which is already very broad here. The car park is at the other side of the bridge.

Additional things to do in Ordesa

23

– Walk through the Ara gorge

Full day, easy-moderate

The trail through the Ara gorge, a continuation of the Bujaruelo valley, forms somewhat of a mix between the great Canyon of Ordesa (route 15) and the open landscape of Otal (route 16). You can spend a full day here easily. There are many sun-soaked flowery slopes to satisfy your butterfly wishes. In comparison to Ordesa, there is more acidic bedrock here (though not exclusively), which makes for a different flora. About an 1.5 hours from Bujaruelo (the starting point), just beyond the high cliffs on the other side of the valley, there is a waterfall to your right. This is an excellent site for butterflies, and one of the few places where the rare Pyrenean Lily (p. 62) and Yellow Garlic grow.

24 – Bus to the alpine pastures

An absolute highlight for its scenery, birds, wildflowers, butterflies, is the bus trip to the alpine meadows south of the Ordesa canyon. It is your only option to get to high altitude habitat without having to make long and strenuous walks. You can take the bus

For locations of these sites, see map on page 185.

View into the Ordesa gorge from the endpoint of the bus (site 24).

Yellow Garlic, endemic to the Pyrenees and Iberian Peninsula.

The warmth-loving Knapweed Fritillary flies along the banks of the Ara river (site 25).

either in Torla or Nerín. This is not a regular bus, but a four wheel drive version that services for tourists between June and September. You’ll need to make a reservation, either on monteperdidobus.com / phone: 974 489 024 (service from Nerín) or ordesataxis.ordesa.com / phone: 630 418 918 (service from Torla). Ask your hotel or camp site to help you to book. A ticket costs € 30.00 (2015 prices).

The bus makes four stops at different viewpoints over the Ordesa canyon, allowing you time to look around. At each of these points the scenery is breath-taking. Scan woodland edges down in the valley for Chamois and look around for Marmots around the viewpoints. Lammergeier, Golden Eagle, Egyptian Vulture, Alpine Accentor and Citril Finch are not uncommon. Snowfinch is sometimes seen at the easternmost viewpoint. Plants of interest include Long-leaved and Livelong Saxifrages, Edelweiss and the rare Pyrenean Yam (p. 63). Look for these (with care!) at the cliff’s edge and in places with loose rocks. Apollo, Mountain Clouded Yellow, Western Brassy Ringlet, Glandon and Eros Blues are a taste of the butterflies here.

The bus ride takes about 4 hours. If it is not too busy, and you speak some Spanish, it is worth trying to negotiate to be dropped off at one of these points and to be picked up again by another bus later in the afternoon. This allows you more time and freedom of movement.

25 – River Ara between Boltaña and Aínsa GPS: 42.43304, 0.08448

The Ara River runs its course freely for 70 km before joins the River Cinca in the town of Aínsa. It is thereby the only major river in the Spanish Pyrenees that is free of dams. Between Boltaña and Aínsa the wide riverbed and its natural vegetation gives shelter to a Mediterranean birdlife that is common further down in Spain, but rather rare in the Pyrenees. In spring and summer attractive birds include Bee-eater, Woodchat Shrike, Scops Owl, Melodious Warbler, Golden Oriole, Nightingale, Wryneck and Turtle Dove. Booted Eagle is common in the surroundings. Grey Wagtail, Dipper and Otter live in the river all year round. The area is bound to be attractive for dragonflies, but has, as far as we know, never been surveyed. We found ‘southern’ butterflies like Knapweed and Spotted Fritillary. Green Lizard, here at its southern edge, also occurs.

There are various options to explore. From the village of Margudgued (just southeast of Boltaña) is an easy 6.2 km ‘Via Verde’ cycling/walking path in the valley. Park at Margudgued, leave the tiny village by Calle Mayor and just continue. Alternatively or additionally, you can turn left just after passing a small stream and follow the dam along the river. This site is easily combined with a visit to the historic town of Aínsa.

26 – The valley of Plan 6 hours, moderate

The valley of Plan is perhaps the most isolated of all the central Pyrenean valleys, being completely surrounded by mountains and only accessible through a single narrow gorge. In the few villages the local patois, Aragonese, is still the principal language. Outside the summer months, few people visit the area and wildlife then finds the tranquillity that it needs. The extensive pine forests support rarities such as Tengmalm’s Owl, the vulnerable Capercaillie and a large population of Chamois. Most way-marked walks depart from the Viados refuge at the northern end of the valley. We very much recommend going up from the village of Saravillo at the beginning of the valley to the Ibón de Plan. With a good car (preferably 4x4) and with suitable care, a large part of the track can be driven. The Basa de la Mora or Ibón de Plan is home to Pyrenean Brook Newt and the surroundings support many butterflies, Ring Ouzel and Citril Finch. It is a marvellous butterfly area with many ringlets (e.g. De Prunner’s, Spanish Brassy and Piedmont Ringlets).

The Ibón (mountain lake) of Plan.

TOURIST INFORMATION & OBSERVATION TIPS

Travel

Travelling to Huesca

Most visitors to Huesca come by car from the west via the valley of Canfranc (i.e. the road between Pau and Jaca), or the east from Montréjau to Vielha. There are two other approaches on smaller roads via Col de Portalet (connecting with Sabiñánigo) and Bielsa (connecting with Aínsa).

There are good connections by train from Paris (via Irún and Zaragoza). Another good option, if a bit more hassle, is to take the train to Pau and subsequently the bus connection to Canfranc, from which the train continues to Huesca.

Travelling in Huesca

By far the easiest way to travel in Huesca is by car. The roads are good and there is no shortage of petrol stations. There are plenty of safe places to stop besides the road and explore the surroundings. Be aware, though, that it is illegal to park on the road itself and that the Guardia Civil actively check for violations (all 4 wheels need to be off the tarmac).

Discovering Huesca by bicycle is a challenge. Villages are far apart and in the lowlands, the temperatures are high and shade is scarce. In the mountains, the weather is capricious, with heat and cold, sun and rain all possible within a single day. That said, many sports cyclists visit the Pyrenees and in the lowlands the traffic is light enough for it to be safe. If you plan to visit Huesca by bicycle, you need to plan carefully in the lowlands as, unlike the Pyrenees and the Sierras Exteriores, there are few hotels and hostels in the Monegros (see page 220). You’d best adapt to the Spanish pace of life, with activity in the mornings and evenings and taking long lunch breaks in the local bar. The food is usually good and cheap, especially if you opt for a menú del día.

Travelling through Huesca on public transport is possible, but requires patience. From most larger centres (Huesca, Jaca, Sabiñánigo, Aínsa, Barbastro) there are bus services to nearly all villages in the province, but often there is only one bus a day. Consequently, speaking at least rudimentary Spanish is advisable if you are to get by. It is advisable to check bus schedules in advance via alosa.es

BIRD LIST

The numbers between the brackets (…) refer to the routes from page 115 onwards.

Geese and ducks Mostly in winter and up to early spring, there are Mallard, Shoveler, Gadwall, Teal, Tufted Duck, Pochard and Pintail (1, 3, 5, 6). A few ducks breed, including Mallard, Shelduck (3) and Red-crested Pochard (1, 3, 6).

Partridges and Grouse Red-legged Partridge is common throughout the lowlands and the mountain valleys. An endemic subspecies of Grey Partridge breeds in tall-grassed alpine meadows (13, 14, 16). Quail is a scarce breeding bird in areas with cereal plots (1, 3, 4, 5, 11) and again more frequently in alpine meadows (13, 14, 16). There is a relict population of Capercaillie in the general Benasque area, which is highly threatened. For Ptarmigan, one needs to go on the highest areas of the Pyrenees. Your best chance is when climbing up from Llauset (21).

Grebes Great Crested is common but Little Grebe fairly rare on reservoirs with vegetated shores (1, 3, 5, 6). Black-necked Grebe frequents Candasnos lake (3).

Cormorants, herons and egrets Great Cormorant is frequent on large reservoirs in winter. Grey Heron is the most common heron and is widespread in the area. Little Egret breeds in colonies along the Ebro (B on page 137). Great White Egret does not (yet) breed, but is fairly widespread in the lowlands in winter (1, 3, 5, 6), Little Bittern has become rare with only a handful of observations in summer. Sariñena (5) is the stronghold of Great Bittern. Purple Heron is common at the Ebro (B on page 137) and occurs at Sariñena (3), Sotonera (6) and El Pas (C on page 138). Night Heron breeds in the Galachos del Ebro – site B on page 137. Cattle Egret occurs locally around herds (e.g. south of Huesca – 5 and El Pas, page 138).

Storks White Stork breeds in good numbers in several towns and villages along rivers in the Monegros (4) and in the Somontano. Villages and towns with many White Storks are Monzón, Alcolea de Cinca, Sena and Lanaja. Black Stork migrates in low numbers.

Vultures Vultures are the most conspicuous birds of the region. The Griffon Vulture is the most frequent bird and there are excellent viewpoints on routes 9, 10 and 12. Egyptian Vultures, unlike Griffons, are not colonial but are frequent, though declining, throughout the Ebro valley (routes 4, 9, 10). Lammergeier is more difficult to find, but nevertheless fairly common in the Guara and high Pyrenees. The best routes are 8, 9, 11, 13, 15, 16, 18 and the viewpoint at Santa Cilia (D on page 162) is very good as is Revilla (C on page 162). The best way to see and photograph vultures from up close is by witnessing a vulture feeding (D on page 162). Since Black Vulture is introduced in Catalonia, it is sometimes seen in the Sierras Exteriores and High Pyrenees.

Eagles Golden Eagle is the most common eagle, frequenting (though never common) the whole region. Best areas are the Monegros (3, 8, 9, 15, 16) and Sierra de Alcubierre (A on page 137) and the Ordesa area (15-18). Short-toed Eagle is widespread, but never numerous, in the lowlands and Guara (1-11), particularly

in the Somontano (A on page 161). It also occurs in the high mountains (e.g. 15, 17). Booted Eagle is less common, but on the increase. It breeds in the Sierras of Alcubierre and Guara (A on page 137 and A on page 161) and there is a population in La Canal de Berdún near Jaca (12, 13). Bonelli’s Eagle has become very rare, but routes 3 and particularly 7 offer a good chance of success.

Other birds of prey The Osprey is frequent on migration (5, 6 and D on page 138). Marsh Harrier is frequent on 1, 3, 5, with a large winter roost near Huesca (5) and at Sariñena lake (5). Montagu’s Harrier is an uncommon breeding bird of arid fields (best 4). Red Kite is a common breeding bird in the Depresión, especially around Jaca (12, 13) and fairly common in the Somontano, especially in the west (e.g. 5, 6, 10 and D on page 138). There are big winter roosts in the gallery forests (e.g. Flúmen river – 5). Black Kite is very common in spring and summer, particularly south of the Guara (1-11). Buzzard, Sparrowhawk, Goshawk and Honey Buzzard are present in their preferred habitat, mostly in the mountains.

Falcons and kestrels Lesser Kestrel is a local breeding bird of the steppes (3, 4). After breeding, it visits Sotonera (6). Common Kestrel is a widespread, uncommon breeding bird of the lowlands and cliffs in the mountains. Peregrine is widespread and occurs in good numbers, especially in the Guara and in lesser numbers in the high Pyrenees (7, 8, 9, 10, 11). Hobby is a rare breeding bird of riverine forests (5).

Rails, crakes and gallinules Water Rail breeds at Sariñena (5), as Purple Gallinule has done. Coot and Moorhen are present in wetlands (1, 3, 5, 6).

Common Cranes and Bustards The best sites for Common Crane are Laguna de Gallocanta (1 – all winter, with peaks in November and February) and Sotonera (6 – low winter numbers, peak February-March). Several thousands winter in the rice paddies in the south of Huesca province. Both Little and Great Bustard are rare, but with some luck, both may be seen on route 3. Little Bustard also occurs on 1, 2 and 4, but is rare.

Waders, Stone Curlew and Collared Pratincole Little Ringed Plover is a common breeding bird on gravel banks in the large rivers and also occurs near channels in the steppes. Kentish Plover breeds in Gallocanta – 1 and La Playa – 3). Blackwinged Stilt breeds in saline areas (1) and, uncommon, in rice paddies in the Monegros (e.g. 5). Dotterel is a rare bird on passage – best chances on 2 and 3. Stone Curlew is widespread but generally uncommon throughout the lowlands (best 1, 2, 3, 4). Other waders may be seen on passage, most likely in wetlands (best 1, also 4, 6).

Gulls and terns Yellow-legged Gull is an uncommon breeding bird along the Ebro and a frequent winter visitor. Black-headed Gull breeds at Gallocanta, sometimes near Sariñena and in the Cinca region and is a more abundant winter visitor. Gull-billed Tern breeds at Gallocanta 1. Black and Whiskered Tern is seen on wetlands during migration (e.g. 3).

Sandgrouse The Monegros are one of the best places to find sandgrouse in Europe. Both Black-bellied and Pin-tailed Sandgrouse breed in good numbers at 2, 3 and 4, but you need to be out in the field early to find them (see page 225).

Pigeons and doves Feral pigeons are widespread, but fairly ‘pure’ wild Rock Dove breed at Vadiello (9). Wood Pigeon and Collared Dove are common in their preferred habitat, though not frequent in the mountains. Stock Dove is a bird of the lower Ebro basin and Turtle Dove is especially abundant in riverine forest, breeding also in holm oak and Aleppo pine forest (site A on page 137 and sites A on page 161 and F on page 163).

Cuckoos Cuckoo is common throughout. Great Spotted Cuckoo breeds locally in open pine woods in the lowlands (e.g. 5 and site A on page 137). April and May are the best months to find this secretive bird.

Owls Barn Owl is frequent in villages. Tawny and Long-eared Owls are hard to spot, but frequently heard. Scops Owl is also widespread and frequent, but more often heard than seen. It breeds even in the city park of Huesca. Eagle Owl is fairly common on rock ledges in the mountain ranges of the Guara and further south. Piracés (5) is one of the better spots to hear it. Little Owl is surprisingly uncommon (3 is best). Tengmalm’s Owl breeds high in the mountains. The most reliable site is at the beginning of the Pineta valley (18). Take a track left just after the Pineta reservoir, continue in the direction la Estibeta and listen for its call in the pine forest.

Nightjars Nightjar prefers open woodland – mostly pine, less often in holm oak wood, where it can be quite common (e.g. 5, 6, 11, 12, A on page 137). Red-necked Nightjar breeds in the southeastern corner of the Huesca province in Juniper scrub and open steppe vegetation with at least some trees (4, 5, A on page 137).

Swifts Common Swift is widespread. Pallid Swift has a small population in the city centre of Zaragoza. Alpine Swift breeds in the Guara and high Pyrenees (e.g. 8, 9, 10, 15, 16) and near Alcolea (4). They are easiest to see during the morning and evening as, in the middle of the day, they often fly very high.

Bee-eater, Roller and Hoopoe Hoopoe is widespread throughout the Somontano and Ebro valley (e.g. 2, 3, 4, 5, A on page 181). Bee-eater is very common in some parts of the lowlands (best 5, but also 3, 4, A on page 161 and A on page 181). There is a good, but localised population of Roller in the south-east of our area (4, El Pas, page 138).

Woodpeckers Great Spotted Woodpecker is common and widespread. Iberian Green Woodpecker is fairly rare and Wryneck fairly common, mostly along rivers, throughout the area e.g. (5, B on page 137, D on page 138 and A on page 181),. Lesser Spotted Woodpecker is rare bird of mature riverine forests (e.g. along the Ebro). Black Woodpecker is widespread in old Scots pine and beech forests (12, 13, 14, 15, 16). The very rare (under 100 pairs in Spain) White-backed Woodpecker occurs in old Beech forests just west (Selva de Irati; Navarra) and north (forest of Somport in France) and has been reported in the past in the Selva de Oza (13) and Ansó (site B on page 181).

Larks see also box on page 25. Skylark breeds in alpine meadows (14, 18, 21, site B on page 202) and winters in the Ebro basin. Woodlark is fairly frequent in open woodland (11, 14, 20, site A on page 161 and site A on page 137). Crested Lark occurs along roads in the Somontano and Ebro basin, while Thekla Lark is frequent in

bushy steppes (2, 3, 4, 5). Calandra Lark is common in grain fields in the steppes (1-6), and Short-toed Lark is found on ploughed fields and grassy steppes (1-5). Look for Lesser Short-toed Lark in salt pans (2, 3) and Dupont’s Lark in flat bushy steppes (1, 2).

Swallows and martins Barn Swallow and House Martin are common throughout. Red-rumped Swallow is a scarce breeding bird. Crag Martin is common near cliffs in the mountains (e.g. 5, 8, 9, 10, 13, 15, 16, 17, 20, 21).

Pipits and wagtails Tawny Pipit is a scarce breeding bird (1, 2, 3). Meadow Pipit a common winter bird in the lowlands. Water Pipit breeds in alpine pastures (13, 14, 15, 18, 21, site B on page 202) and winters in the Ebro basin. Few White Wagtails breed, but it is very abundant in the lowlands during winter. Grey Wagtail occurs along streams in the mountains (7, 13, 15, 17, 18, 20), while Yellow Wagtail is mostly seen on migration.

Dipper and accentors Dipper breeds in mountain streams (13, 14, 15, 17, 19). Dunnock breeds in open pine forests, above 1,000 metres (e.g. 11, 13, 14, 18, 19, 20). Alpine Accentor breeds high up in alpine meadows (21, B on page 202 and B on page 215). In winter it descends and is frequently seen at rocky places (9, 10, 11, 12, El Portalet – 14).

Thrushes, chats, wheatears, redstarts and allies Song Thrush breeds in beech and mixed mountain woodlands (e.g. 13, 15, 18), being a common winter visitor in the south. Mistle Thrush is a fairly common resident of mountain pine woods (e.g. 11, 12, 13, 14, 19, 20). Ring Ouzel is often difficult to find, but breeds all over the high mountain pinewoods just under the treeline (e.g. 13, 14, 15, 16, 18, 19, site C on page 182 an D on page 203). Blackbird is common in its usual habitat, Fieldfare and Redwing are irregular winter visitors. At higher altitudes Robins are common breeding birds, mainly wintering in lower places. Nightingale is very common in wet areas mostly in the lowlands. Blue Rock Thrush is most frequent in rocky areas in the Guara (7, 8, 9, 10) and a resident. Common Rock Thrush breeds mostly higher up in the mountains, in rocky terrain around the tree line (13, 14, 15, 18, 20, 21 and sites C on page 182 and B on page 202). Stonechat breeds in low numbers and is abundant in the Ebro basin in winter. Whinchat can be found during migration and is a rare breeding bird of alpine meadows (e.g. 14).

Northern Wheatear is frequent in stony areas above and around the treeline (e.g. 13, 14, 15, 18, 19, 21, B on page 202) and an uncommon breeding bird in the steppe (e.g. 3 – common at 1). Black-eared Wheatear is fairly common in stony steppes (e.g. 3, 4, site A on page 137). Black Wheatear is typical of dry, sandstone cliffs and rocky terrain on the south slopes of the Guara. It is in decline, but still fairly easily found at 3, 4, 5 and 10. Black Redstart is common in villages and above the treeline. Few Common Redstarts breed, but they are seen on migration.

‘Sylvia’ warblers Sardinian and Dartford Warbler are common birds of Mediterranean scrubland (1, 3 to 11). Subalpine Warbler is frequent in open Holm Oak forest with scrub (e.g. 6, 7, 8, 9, site A on page 161). Orphean Warbler is difficult to find, but locally common in dry areas with scattered trees, like Aleppo Pines, Spanish Junipers and Holm Oak (8, site A on page 137). Spectacled Warbler

Routes

Route 1: La Laguna de Gallocanta

Route 2: The steppes of Belchite

Route 3: Monegros 1 – from Sástago to Candasnos

Route 4: Monegros 2 – the AlcoleaOntiñena-Ballobar triangle

Route 5: From Huesca to the Alcubierre mountains

Route 6: Valdabra Reservoir

Route 7: Sotonera reservoir

Route 8: Santa Ana reservoir

Route 9: las paserelas de Alquézar

Route 10: Vadiello and Roldán – the great gates to the Guara

Route 11: Los Mallos de Riglos

Route 12: The wild northern Guara

Route 13: San Juan de la Peña and Oroel

Route 14: The Hecho valley

Route 15: The Tena Valley and El Portalet

Route 16: The Valley of La Sarra

Route 17: The Ordesa canyon

Route 18: Bujaruelo and the Otal valley

Route 19: The Añisclo gorge

Route 20: Escuaín

Route 21: Revilla – The Lammergeier Trail

Route 22: The Pineta valley

Route 23: El Turbón

Route 24: Benasque

Route 25: The high mountain lake of

Sites

Site 1: The Ebro river and Galacho de la Alfranca

Site 2: The Sierra de Alcubierre and more Monegro

Site 3: Valfarta

Site 4: The river woodlands of the Cinca

Site 5: El Pas and Finca San Miguel

Site 6: Embalse de San Salvador

Site 7: The Río Vero gorge

Site 8: The Mascún Gorge and Otín heights

Site 9: The Somontano road

Site 10: Along Río Alcanadre at Bierge

Site 11: Las Gorgas de San Julian

Site 12: Holm Oak forest Carrascal de Nisano

Site 13: Loarre Castle

Site 14: Mallos de Agüero Llauset

Site 15: Berdún, Veral river

Site 16: Ansó valley

Site 17: Aragües del Puerto

Site 18: Las Guixas cave

Site 19: Ibon de Tramacastilla de Site Tena

Site 20: Panticosa ski slopes

Site 21: Balneario de Panticosa

Site 22: Ripera valley by tourist train

Site 23:– Walk through the Ara gorge

Site 24: Bus to the alpine pastures

Site 25: River Ara between Boltaña and Aínsa

Site 26: The valley of Plan

Site 27: Valley of Estós

Site 28: Hospital de Benasque

Site 29: Valley of Vallibierna

Site 30: Ski resort of Cerler

pamplona

tudela

Map of The black sites on the Sierras western sites 27-30

Los Monegros

the Spanish Pyrenees

black numbers refer to the routes in this book; the blue numbers refer to the pages 135-137 (sites 1-6 in the Ebro valley), pages 157- 161 (sites 7-14 in Sierras Exteriores and Somontano), pages 181-184 (walks and sites 15-22 in the valleys), pages 209-211 (sites 23-26 in Ordesa), pages 224-225 (walks and 27-30 near Benasque).

CROSSBILL GUIDES FOUNDATION

Huesca (Spain) is the northern, and most diverse, of Aragon’s three provinces. It covers both the wild High Pyrenees, their wooded foothills and the steppes in the basin of the Ebro. There are few areas in Europe with such a diversity of landscapes, flora and fauna. From the Alpine heights of Ordesa to dry semi-desert of Belchite, this guidebooks shows you the best sites and reveals their flora and fauna.

• The guide that covers the wildflowers, birds and all other wildlife

• Routes, where-to-watch-birds information and other observation tips

• Insightful information on landscape and ecology

“Crossbill Guides – Everything you need to turn up in the right place and at the right time to find some of the best wildlife in Europe”

Chris Packham – BBC Springwatch